The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii

The famous archaeological treasure is falling into scandalous decline, even as its sister city Herculaneum is rising from the ashes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/c1/87c180dd-7e31-4db7-a3a0-85dce87dd950/julaug2015_a11_pompeii.jpg)

On a sweltering summer afternoon, Antonio Irlando leads me down the Via dell’Abbondanza, the main thoroughfare in first-century Pompeii. The architect and conservation activist gingerly makes his way over huge, uneven paving stones that once bore the weight of horse-drawn chariots. We pass stone houses richly decorated with interior mosaics and frescoes, and a two-millennial-old snack bar, or Thermopolium, where workmen long ago stopped for lunchtime pick-me-ups of cheese and honey. Abruptly, we reach an orange-mesh barricade. “Vietato L’Ingresso,” the sign says—entry forbidden. It marks the end of the road for visitors to this storied corner of ancient Rome.

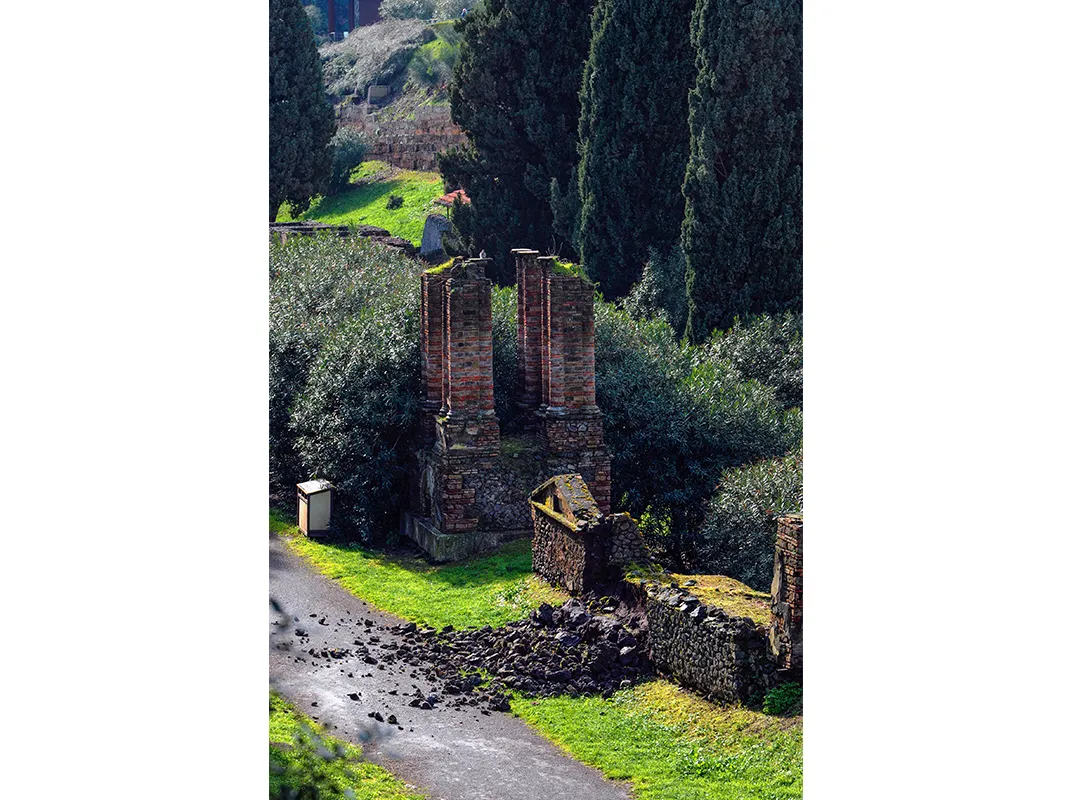

Just down the street lies what Turin’s newspaper La Stampa called Italy’s “shame”: the shattered remains of the Schola Armaturarum Juventus Pompeiani, a Roman gladiators’ headquarters with magnificent paintings depicting a series of Winged Victories—goddesses carrying weapons and shields. Five years ago, following several days of heavy rains, the 2,000-year-old structure collapsed into rubble, generating international headlines and embarrassing the government of then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. The catastrophe renewed concern about one of the world’s greatest vestiges of antiquity. “I almost had a heart attack,” the site’s archaeological director, Grete Stefani, later confided to me.

Since then this entire section of Pompeii has been closed to the public, while a committee appointed by a local judge investigates the cause of the collapse. “It makes me angry to see this,” Irlando, a genial 59-year-old with a mop of graying hair, tells me, peering over the barrier for a better look.

Irlando enters the nearby Basilica, ancient Pompeii’s law court and a center of commerce, its lower-level colonnade fairly intact. Irlando points out a stone lintel balanced on a pair of slender Corinthian columns: Black blotches stain the lintel’s underside. “It’s a sign that water has entered into it, and it’s created mold,” he tells me with disgust.

A few hundred yards away, at the southern edge of the ruins, we peer past the cordoned-off entrance to another neglected villa, in Latin a domus. The walls sag, the frescoes are fading into a dull blur, and a jungle of chest-high grass and weeds chokes the garden. “This one looks like a war zone,” says Irlando.

Since 1748, when a team of Royal Engineers dispatched by the King of Naples began the first systematic excavation of the ruins, archaeologists, scholars and ordinary tourists have crowded Pompeii’s cobblestone streets for glimpses of quotidian Roman life cut off in medias res, when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius suffocated and crushed thousands of unlucky souls. From the amphitheater where gladiators engaged in lethal combat, to the brothel decorated with frescoes of couples in erotic poses, Pompeii offers unparalleled glimpses of a distant time. “Many disasters have befallen the world, but few have brought posterity so much joy,” Goethe wrote after touring Pompeii in the 1780s.

And Pompeii continues to amaze with fresh revelations. A team of archaeologists recently studied the latrines and drains of several houses in the city in an effort to investigate the dietary habits of the Roman empire. Middle- and lower-class residents, they found, had a simple yet healthy diet that included lentils, fish and olives. The wealthy favored fattier fare, such as suckling pig, and dined on delicacies including sea urchins and, apparently, a giraffe—although DNA evidence is currently being tested. “What makes Pompeii special,” says Michael MacKinnon of the University of Winnipeg, one of the researchers, “is that its archaeological wealth encourages us to reanimate this city.”

But the Pompeii experience has lately become less transporting. Pompeii has suffered devastating losses since the Schola Armaturarum collapsed in 2010. Every year since then has witnessed additional damage. As recently as February, portions of a garden wall at the villa known as the Casa di Severus gave way after heavy rains. Many other dwellings are disasters in the making, propped up by wooden struts or steel supports. Closed-off roads have been colonized by moss and grass, shrubs sprout from cracks in marble pedestals, stray dogs snarl at passing visitors.

A 2011 Unesco report about the problems cited everything from “inappropriate restoration methods and a general lack of qualified staff” to an inefficient drainage system that “gradually degrades both the structural condition of the buildings as well as their decor.” Pompeii has also been plagued by mismanagement and corruption. The grounds are littered with ungainly construction projects that squandered millions of euros but were never completed or used.In 2012, Irlando discovered that an emergency fund set up by the Italian government in 2008 to shore up ancient buildings was instead spent on inflated construction contracts, lights, dressing rooms, a sound system and a stage at Pompeii’s ancient theater. Rather than creating a state-of-the-art concert venue, as officials claimed, the work actually harmed the historic integrity of the site.

Irlando’s investigation led to government charges of “abuse of office” against Marcello Fiori, a special commissioner given carte-blanche power by Berlusconi to administer the funds. Fiori is accused of having misspent €8 million ($9 million) on the amphitheater project. In March, Italian authorities seized nearly €6 million ($7 million) in assets from Fiori. He has denied the accusations.

Caccavo, the Salerno-based construction firm that obtained the emergency-fund contracts, allegedly overcharged the state on everything from gasoline to fire-prevention materials. Its director was placed under house arrest. Pompeii’s director of restoration, Luigi D’Amora, was arrested. Eight individuals are facing prosecution for charges including misallocation of public funding in connection with the scandal.

“This was a truffa, a scam,” says Irlando, pointing out a trailer behind the stage where the police have stored theatrical equipment as evidence of corruption. “It was all completely useless.”

Administrative malpractice is not unheard of in Italy, of course. But because of the historic importance and popular appeal of Pompeii, the negligence and decay in evidence there are beyond the pale. “In Italy, we have the greatest collection of treasures in the world, but we don’t know how to manage them,” says Claudio D’Alessio, the former mayor of the modern city of Pompei, founded in 1891 and located a few miles from the ruins. A recent editorial in Milan’s Corriere della Sera declared that Pompeii’s disastrous state was “the symbol of all the sloppiness and inefficiencies of a country that has lost its good sense and has not managed to recover it.”

For its part, Unesco issued an ultimatum in June 2013: If preservation and restoration efforts “fail to deliver substantial progress in the next two years,” the organization declared, Pompeii could be placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger, a designation recently applied to besieged ancient treasures such as Aleppo and the Old City of Damascus in Syria.

**********

Pompeii’s troubles have come to light at the very moment that its twin city in first-century tragedy—Herculaneum—is being celebrated for an amazing turnaround. As recently as 2002, archaeologists meeting in Rome said Herculaneum was the “worst example of archaeological conservation in a non-war torn country.” But since then, a private-public partnership, the Herculaneum Conservation Project, established by the American philanthropist David W. Packard, has taken charge of the ancient Roman resort town by the Bay of Naples and restored a semblance of its former grandeur. In 2012, Unesco’s director general praised Herculaneum as a model “whose best practices surely can be replicated in other similar vast archaeological areas across the world” (not to mention down the road at Pompeii).

Herculaneum’s progress made news just a few months ago, when researchers at the National Research Council in Naples announced a solution to one of archaeology’s greatest challenges: reading the texts of papyrus scrolls cooked at Herculaneum by the fiery pyroclastic flow. Scientists had employed every imaginable tactic to unlock the secrets of the scrolls—prying them apart with unrolling machines, soaking them in chemicals—but the writing, inscribed in carbon-based ink and indistinguishable from the carbonized papyrus fibers, remained unreadable. And unspooling the papyrus caused further damage to the fragile material.

The researchers, headed by physicist Vito Mocella, applied a state-of-the-art method, X-ray phase-contrast tomography, to examine the writing without harming the papyrus. At the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, high-energy beams bombarded the scrolls and, by distinguishing contrasts between the slightly raised inked letters and the surface of the papyrus, enabled scientists to identify words, written in Greek. It marked the beginnings of an effort that Mocella calls “a revolution for papyrologists.”

**********

It was on the afternoon of August 24, A.D. 79, that people living around long-dormant Mount Vesuvius watched in awe as flames shot suddenly from the 4,000-foot volcano, followed by a huge black cloud. “It rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided,” wrote Pliny the Younger, who, in a letter to his friend, the historian Tacitus, recorded the events he witnessed from Misenum on the northern arm of the Bay of Naples, about 19 miles west of Vesuvius. “Sometimes it looked white, sometimes blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it.”

Volcanologists estimate that the eruptive column was expelled from the cone with such force that it rose as high as 20 miles. Soon a rain of soft pumice, or lapilli, and ash began falling over the countryside. That evening, Pliny observed, “on Mount Vesuvius broad sheets of fire and leaping flames blazed at several points, their bright glare emphasized by the darkness of night.”

Many people fled as soon as they saw the eruption. But the lapilli gathered deadly force, the weight collapsing roofs and crushing stragglers as they sought protection beneath staircases and under beds. Others choked to death on thickening ash and noxious clouds of sulfurous gas.

In Herculaneum, a coastal resort town about one-third Pompeii’s size, located on the western flank of Vesuvius, those who elected to stay behind met a different fate. Shortly after midnight on August 25, the eruption column collapsed, and a turbulent, superheated flood of hot gases and molten rock—a pyroclastic surge—rolled down the slopes of Vesuvius, instantly killing everyone in its path.

Pliny the Younger observed the suffocating ash that had engulfed Pompeii as it swept across the bay toward Misenum on the morning of August 25. “The cloud sank down to earth and covered the sea; it had already blotted out Capri and hidden the promontory of Misenum from sight. Then my mother implored, entreated and commanded me to escape as best I could....I refused to save myself without her and grasping her hand forced her to quicken her pace....I looked round; a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood.” Mother and son joined a crowd of wailing, shrieking and shouting refugees who fled from the city. “At last the darkness thinned and dispersed into smoke or cloud; then there was genuine daylight....We returned to Misenum...and spent an anxious night alternating between hope and fear.” Mother and son both survived. But the area around Vesuvius was now a wasteland, and Herculaneum and Pompeii lay entombed beneath a congealing layer of volcanic material.

**********

The two towns remained largely undisturbed, lost to history, through the rise of Byzantium, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In 1738, Maria Amalia Christine, a nobleman’s daughter from Saxony, wed Charles of Bourbon, the King of Naples, and became entranced by classical sculptures displayed in the garden of the royal palace in Naples. A French prince digging in the vicinity of his villa on Mount Vesuvius had discovered the antiquities nearly 30 years earlier, but had never conducted a systematic excavation. So Charles dispatched teams of laborers and engineers equipped with tools and blasting powder to the site of the original dig to hunt more treasures for his queen. For months, they tunneled through 60 feet of rock-hard lava, unearthing painted columns, sculptures of Roman figures draped in togas, the bronze torso of a horse—and a flight of stairs. Not far from the staircase they came to an inscription, “Theatrum Herculanense.” They had uncovered a Roman-era town, Herculaneum.

Digging began in Pompeii ten years later. Workers burrowed far more easily through the softer deposits of pumice and ash, unearthing streets, villas, frescoes, mosaics and the remains of the dead. “Stretched out full-length on the floor was a skeleton,” C.W. Ceram writes in Gods, Graves and Scholars: The Story of Archaeology, a definitive account of the excavations, “with gold and silver coins that had rolled out of bony hands still seeking, it seemed, to clutch them fast.”

In the 1860s a pioneering Italian archaeologist at Pompeii, Giuseppe Fiorelli, poured liquid plaster into the cavities in the solidified ash created by the decomposing flesh, creating perfect casts of Pompeii’s victims at the moment of their deaths—down to the folds in their togas, the straps of their sandals, their agonized facial expressions. Early visitors on the Grand Tour, like today’s tourists, were thrilled by these morbid tableaux. “How dreadful are the thoughts which such a sight suggests,” mused the English writer Hester Lynch Piozzi, who visited Pompeii in the 1780s. “How horrible the certainty that such a scene might be all acted over again tomorrow; and that, who today are spectators, may become spectacles to travelers of a succeeding century.”

**********

Herculaneum remained accessible only by tunnels through the lava until 1927, when teams supervised by Amedeo Maiuri, one of Italy’s pre-eminent archaeologists, managed to expose about a third of the buried city, around 15 acres, and restore as faithfully as possible the original Roman constructions. The major excavations ended in 1958, a few years before Maiuri’s retirement in 1961.

I’m standing on a platform suspended above Herculaneum’s ancient beachfront, staring down at a grisly scene. Inside stone archways that framed the entrance to a series of boat houses, 300 skeletons huddle, frozen for eternity in positions they had assumed at the moment of their deaths. Some sit propped against stones, others lie flat on their backs. Children nestle between adults; a few loners sit by themselves. “They didn’t know what was going to happen to them. Maybe they were all waiting for rescue,” says Giuseppe Farella, a conservator. Instead, they were overcome by a 1,000-degree Fahrenheit avalanche of gas, mud and lava, which burned the flesh off their bones, then buried them. “It must have been very painful, but very fast,” says Farella.

The exhibit, which opened in 2013, is among the latest initiatives of the Herculaneum Conservation Project, supported by the Packard Humanities Institute in Los Altos, California (founded by David W. Packard, an heir to the Hewlett-Packard fortune), in partnership with the British School at Rome, and the Superintendency for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples and Pompeii, the government body that administers the site. Since the project’s founding in 2001, it has spent €25 million ($28.5 million) on initiatives that have revitalized these once-collapsing ruins.

The project began to take shape one evening in 2000, when Packard (who declined to be interviewed for this article) considered ideas for a new philanthropic endeavor with his friend and renowned classics scholar Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, then director of the British School at Rome. Hadrill recommended Herculaneum. “The superintendent showed [Packard] around the site; two-thirds was closed to the public because it was falling down,” Sarah Court, the project’s press director, tells me in a trailer beside the ruins. “Mosaics were crumbling, frescoes were falling off walls. Roofs were collapsing. It was a disaster.”

Herculaneum, of course, faced cronyism and financial shortages that Pompeii has today. But Packard staffers took advantage of private money to hire new specialists. One of the site’s biggest problems, lead architect Paola Pesaresi tells me as we walked the grounds, was water. The ancient city sits some 60 feet below the modern city of Herculaneum, and rain and groundwater tends to collect in pools, weakening foundations and destroying mosaics and frescoes. “We had to find a delicate way to prevent all this water from coming in,” she says. The project hired engineers to resurrect the Roman-era sewage system—tunnels burrowed three to six feet beneath the ancient city—two-thirds of which had already been exposed by Maiuri. They also installed temporary networks of aboveground and underground drainpipes. Pesaresi ushers me through a tunnel chiseled through the lava at the entrance to the ruins. Our conversation is nearly drowned out by a torrent of water being pumped from beneath Herculaneum into the Bay of Naples.

We stroll down the Decumanus Maximus, a street where public access has long been quite limited, because of the danger of falling stones and collapsing roofs. After millions of dollars of work, the facades are secure and the houses are dry; the street fully opened in 2011. Workers have painstakingly restored several two-story stone houses, piecing together original lintels of carbonized wood—sealed for 2,000 years in their oxygen-less tomb—along with terra-cotta-and-wood roofs, richly frescoed walls, mosaic floors, beamed ceilings and soaring atriums.

Pesaresi leads me into the Casa del Bel Cortile, a recently renovated, two-story home with an open skylight, a mosaic-tiled floor and a restored roof protecting delicate murals of winged deities posed against fluted columns. Unlike Pompeii, this villa, as well as numerous others in Herculaneum, conveys a sense of completeness.

Art restorers are stripping away layers of paraffin that restorers applied between the 1930s and 1970s to prevent paint from cracking on the city’s magnificent interior frescoes. “The early restorers saw that the figurative scenes were flaking, and they asked themselves, ‘What can we do?’” Emily MacDonald-Korth, then of the Getty Conservation Institute, tells me during a lunch break inside a two-story villa on the Decumanus Maximus. The wax initially worked as a kind of glue, holding the images together, but ultimately speeded the frescoes’ disintegration. “The wax bonded with the paint, and when water trapped behind the walls sought a way of coming out, it pushed the paint off the walls,” she explains. For some years, the Getty Institute has experimented with laser techniques to restore frescoes, employing a noninvasive approach that strips away wax but leaves paint untouched. Now the Getty team has applied that technique at Herculaneum. “We’re doing this in a controlled way. It won’t burn a hole through the wall,” MacDonald-Korth says.

In 1982, the site’s then director, Giuseppe Maggi, uncovered the volcanic sands of buried Herculaneum’s ancient seafront, as well as a 30-foot-long wooden boat, hurled ashore during the eruption by a seismic tremor-created tsunami. It was Maggi who uncovered the 300 victims of Vesuvius, along with their belongings, including amulets, torches and money. One skeleton, nicknamed “the Ring Lady,” was bedecked in gold bracelets and earrings; her rings were still on her fingers. A soldier wore a belt and a sword in its sheath, and carried a bag filled with chisels, hammers and two gold coins. Several victims were found carrying house keys, as if fully expecting to return home once the volcanic eruption had passed. Though excavation work began in the 1980s, forensics experts more recently photographed the skeletons, made fiberglass duplicates in a lab in Turin and, in 2011, placed them in the identical positions as the original remains. Walkways allow the public to view the reproduced skeletons.

Today, with restoration virtually completed and new landscaping installed, tourists can walk along the sand just as residents of Herculaneum would have done. They can also relive to a remarkable degree the experience of Roman visitors who arrived by sea. “If you were here 2,000 years ago, you would approach by boat and pull up on a beach,” says conservator Farella, leading me along a ramp past the arches opening to the skeletons. In front of us, a steep set of stairs breaches the outer walls of Herculaneum and takes us into the heart of the Roman city. Farella leads me past a bath complex and gymnasium—“to smarten yourself up before you come into town”—and a sacred area where departing travelers sought protection before venturing back to sea. Farther along stands the Villa of the Papyri, believed to be the home of Julius Caesar’s father-in-law. (The villa housed the scrolls now being deciphered by researchers.) It is closed to the public, but plans are underway for a renovation, a project that Farella says “is the next great challenge” at Herculaneum.

He leads me into the Suburban Baths, a series of interconnected chambers filled with huge marble tubs, carved stone benches, tiled floors, frescoes and friezes of Roman soldiers, and a furnace and pipe system that heated the water. Solidified lava, frozen for 2,000 years, pushes up against the doors and windows of the complex. “The bath building was filled with pyroclastic material; excavators chipped it all away,” the conservator says. We pass through the colonnaded entryway of a steam room, down steps leading into a perfectly preserved bathtub. Thick marble walls have sealed in moisture, replicating the atmosphere that Roman bathers experienced. Yet, as if to underscore the reality that even Herculaneum has its troubles, I’m told that parts of this ghostly former center of Roman social life have opened to the public only intermittently, and it is closed now: There’s simply not enough staff to guard it.

**********

In Pompeii, another eight stops along the Circumvesuviana Line, the train that carries thousands of visitors to the site every day, past graffiti-covered stations and scruffy exurbs, the staff is eager to present an impression of new dynamism. In 2012 the European Union gave the go-ahead for its own version of a Herculaneum-style initiative: the Great Pompeii Project, a €105 million ($117.8 million) fund intended to rescue the site.

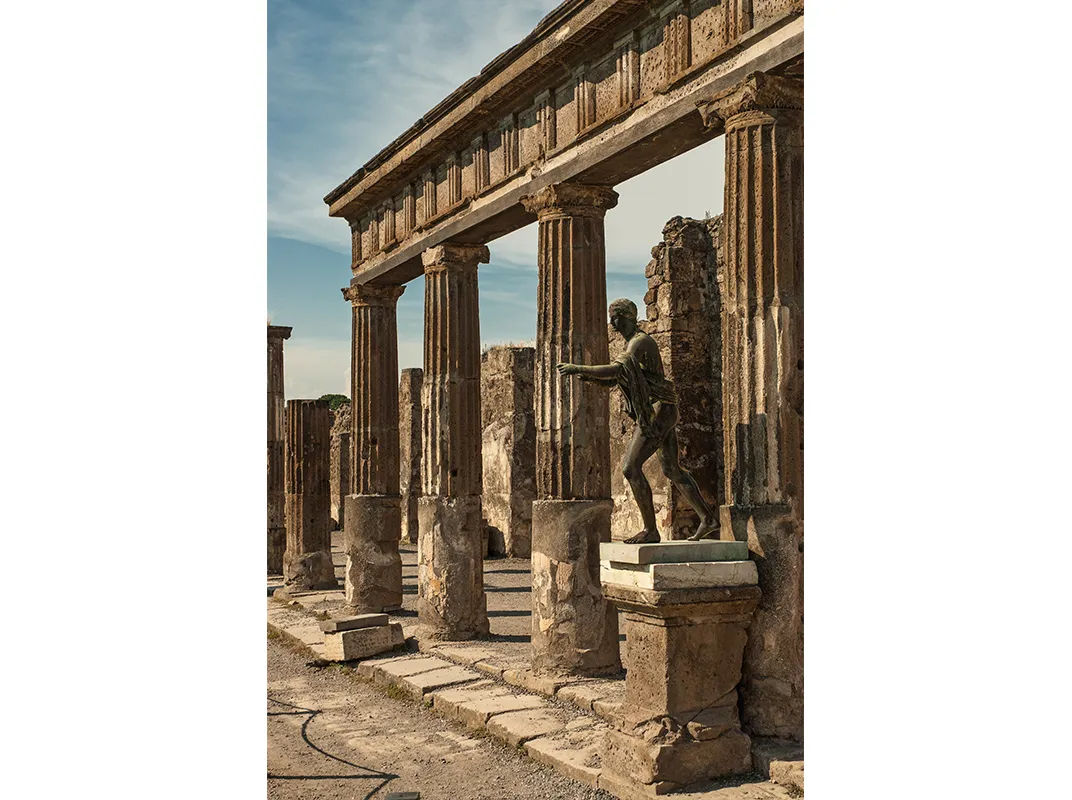

Mattia Buondonno, Pompeii’s chief guide, a 40-year veteran who has escorted notables including Bill Clinton, Meryl Streep, Roman Polanski and Robert Harris (who was researching his best-selling thriller Pompeii), pushes through a tourist horde at the main entrance gate and leads me across the Forum, the marvelously preserved administrative and commercial center of the city.

I wander through one of the most glorious of Pompeii’s villas, the House of the Golden Cupids, a wealthy man’s residence, its interior embellished with frescoes and mosaics, built around a garden faithfully reproduced on the basis of period paintings. Fully restored with funding from the Italian government and the EU, the house was to open the week after my visit, after being closed for several years. “We needed money from the EU, and we needed architects and engineers. We could not realize this by ourselves,” says Grete Stefani, Pompeii’s archaeological director.

I also paid a visit to the Villa dei Misteri, which was undergoing an ambitious renovation. After decades of ill-conceived cleaning attempts—agents that were used included waxes and gasoline—the villa’s murals, depicting scenes from Roman mythology and everyday life in Pompeii, had darkened and become indecipherable. Project director Stefano Vanacore surveyed the work-in-progress. In an 8-by-8-foot chamber covered with frescoes, two contractors wearing hard hats were dabbing the paintings with outsize cotton swabs, dissolving wax. “This stuff has been building up for more than 50 years,” one of the workers told me.

In a large salon next door, others were using laser tools to melt away wax and gasoline buildup. Golden sparks shot off the bearded face of the Roman god Bacchus as the grime dissolved; beside him, a newly revealed Pan played his flute, and gods and goddesses caroused and banqueted. “It’s beginning to look the way it did before the eruption,” Vanacore said.

A wall panel across the room presented a study in contrasts: The untouched half was shrouded in dust, with bleached-out red pigments and smudged faces; the other half dazzled with figures swathed in fabrics of gold, green and orange, their faces exquisitely detailed, against a backdrop of white columns. I asked Vanacore how the frescoes had been allowed to deteriorate so markedly. “It’s a complicated question,” he said with an uneasy laugh, allowing that it came down to “missing the daily maintenance.”

The Villa dei Misteri, which reopened in March, may be the most impressive evidence to date of a turnaround at Pompeii. A recent Unesco report noted that renovation work was progressing on 9 of the 13 houses identified as being at risk in 2013. The achievements of the Great Pompeii Project, along with the site’s routine maintenance program, so impressed Unesco that the organization declared that “there is no longer any question of placing the property on the World Heritage in Danger list.”

Still, despite such triumphs, Pompeii’s recent history of graft, squandered funds and negligence has many observers questioning whether the EU-financed project can make a difference. Some Italian Parliamentarians and other critics contend that Pompeii’s ruins should be taken over in a public-private initiative, as at Herculaneum. Even the Unesco report sounded a cautious note, observing that “the excellent progress being made is the result of ad hoc arrangements and special funding. The underlying cause of decay and collapse...will remain after the end of the [Great Pompeii Project], as will the impacts of heavy visitation to the property.”

**********

To Antonio Irlando, the architect who is Pompeii’s self-appointed watchdog, the only solution to saving Pompeii will be constant vigilance, something that the site’s managers and the Italian government have never been known for. “Italy was once leading the world in heritage conservation,” he says. Squandering Unesco’s good will would be, he declares, “a national shame.”

The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)