The Pay Phone’s Journey From Patent to Urban Relic

The history of the device that is well on its way to becoming, well, history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/ed/15edb26a-2119-4463-9aac-b0a673270c69/payphone-hartford.jpg)

On the corner of Main Street and Central Row in downtown Hartford, Connecticut, a tiny blue sign is attached to the side of grand stone-and-brick building that now houses a CVS but, as the carved stone entablature informs us, was once the home of the Hartford Connecticut Trust Company. That bank was, in turn, home to one of the world's big firsts. The sign is a little too high off the ground and lot of people probably miss it, but it's there: "World's First Pay Telephone. Invented by William Gray and Developed by George A. Long, was installed on this corner in 1889."

By the 1880s, the telephone was a critical component of American infrastructure, but the man on the street looking to make a call had to locate one of the relatively rare agent-operated telephone pay stations and pay a fee to make a call. This could be a great inconvenience, as one William Gray would find out in 1888. The son of Scottish immigrants, Gray was a precision machinery polisher and amateur tinkerer in Hartford who was best known for designing an improved chest protector for baseball catchers that became the game's standard in the 1890s. As for the pay phone though, the story goes that Gray was inspired to create it when, depending on whom you ask, either his boss, his neighbor or the workers at a nearby factory refused to let him use their phone to call a doctor for his ailing wife. Eventually, Gray found a phone and his wife recovered, but he was left with an idea: public telephones.

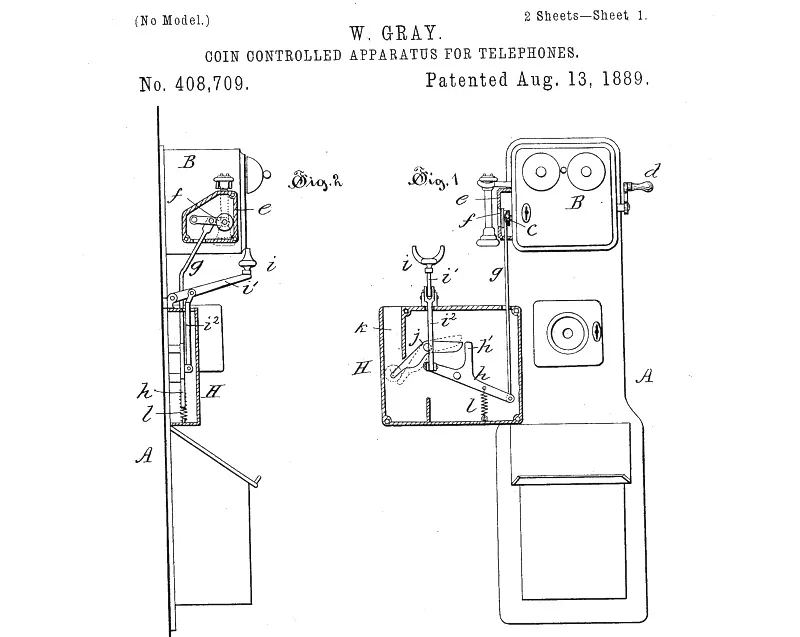

Gray's first prototype device involved a box that covered the mouth of the receiver and would slide away when a coin was deposited. However, it was rejected on the grounds that one coin could buy several phone calls and that if another station was called, the receiver would also have to pay -- obviously not an ideal solution. After a few more failed attempts, Gray found the surprisingly simple solution: a "coin-controlled apparatus" that used a small bell to signify the operator when a coin was deposited (US 408,709), and, a couple years later, a more elaborate "signal device for telephone pay stations" (US 454,470).

In 1891, Gray set up the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company and began installing phones on posts and in cabinets across America. He continued to refine his creation, eventually racking up more than 20 patents related to the pay phone, including innovations related to toll apparatuses, coin holders, call registers and signaling devices. A hundred years later, there were more than 2 million pay phones installed in the United States.

But today, with so many people carrying phones in their pockets (or on their wrists), that number as dwindled dramatically -- by some estimates there are fewer than 300,000. So what to do with all the leftover infrastructure?

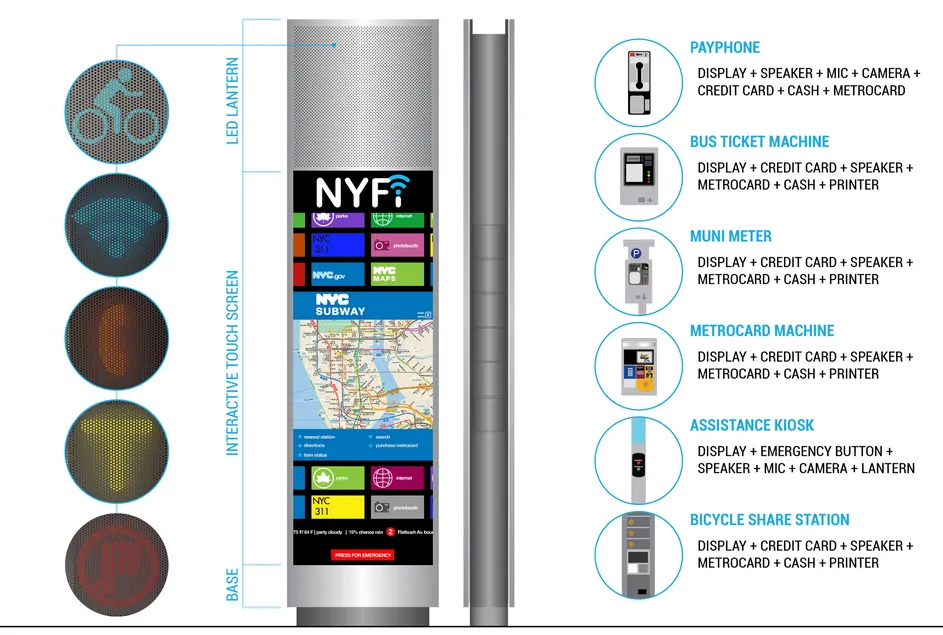

In Britain, old telephone boxes are being turned into tiny art galleries and information booths; in China and South Africa, phone booths are being turned into WiFi routers; and in the United States, well, we're still figuring that out. Next month in New York City, a contract will expire that requires the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT) to maintain the city's 8,000 remaining pay phones. (8,000! Who knew?) In preparation for this moment, last year the DoITT invited "urban designers, planners, technologists and policy experts to create physical and virtual prototypes" that imagine the future of the pay phones. Of the 125 entries, five protoypes recieved awards based on connectivity, creativity, design, function and community impact.

One finalist, Sage and Coombe Architects, won for best connectivity for its proposal NYFi, which "uses existing pay phone infrastructure to create a sleek, interactive portal to public information, goods, and services, a hub for free wireless Internet access, and an open infrastructure for future applications." As cool as this NYC data hub is, there's no guarantee it, or any of the other winning designs, will be implemented. There are a bunch of other, less interesting factors to consider that involve politicians and contracts and subcontractors, but hopefully this "ideas competition" will inspire whatever infrastructural improvements the city decides to make. And maybe someday in the not-too-distant future, we'll see a historic plaque marking the location of the world's last pay phone -- with an augmented reality or holographic component explaining exactly what a pay phone was.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)