The First Children Who Led Sad Lives

Several children of presidents met cruel fates in the first 150 years of our country’s history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/d2/5bd2e3b4-8f11-4ec1-9dd1-bf196ed5ad83/be063163.jpg)

In recent decades, most First Children have led charmed lives. Doted on by an adoring public, they have enjoyed opportunities that are rarely available to other Americans. Chelsea Clinton and Jenna Bush, for example, both parlayed their celebrity into cushy contracts with NBC News. Clinton said to People magazine recently that she sees it as her duty to make sure that her daughter, Charlotte, “realizes how blessed she is—how blessed we [the members of our family] all are.”

For the first century-and-a-half of the republic, however the sons and daughters of presidents often struggled. Historian Michael Beschloss has alluded to their collective misfortune as the “curse of the famous scion.” Several endured accidents or health crises that led to early death. As a group, they experienced much higher rates of alcoholism and mental illness than their peers. Destitution was not uncommon. In the 19th century, a few First Children did achieve success—Lincoln’s eldest son, Robert, eventually became the CEO of the Pullman Palace Car Company and Webb Hayes, the second son of Rutherford B. Hayes, helped to found the corporate behemoth, Union Carbide—but these cases were the exception rather than the rule.

In stark contrast to Clinton and Bush, Abigail (“Nabby”) Adams, the eldest child of John Adams, lived in abject poverty for most of her adult life. She suffered through a difficult marriage to William Smith, a mentally unstable former aide-de-camp to George Washington. Smith would repeatedly abandon her and their four children for months—sometimes even years—at a time. In the late 1790s, when a few of Smith’s speculative ventures went belly up, Nabby lived with her husband in a tiny cottage on the grounds of a debtors’ prison. “My dear sister’s destiny might have been better,” Adams’s second son, Thomas, wrote of Nabby, who died of cancer at 48.

Nabby’s brother, Charles, Adams’s third son, met an even crueler fate. Though he passed the bar in 1792, the Harvard grad never could make a decent living in his chosen profession. A chronic alcoholic, who was also a serial adulterer, Charles often lived apart from his wife and two daughters. Weighed down by worry over the distress of both Nabby and Charles, John Adams confessed to his wife, Abigail, a couple of years into his administration, “My children give me more pain than all my enemies.” In the fall of 1799, Adams disowned Charles, whom he never spoke to again. A year later, the destitute Charles died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 30.

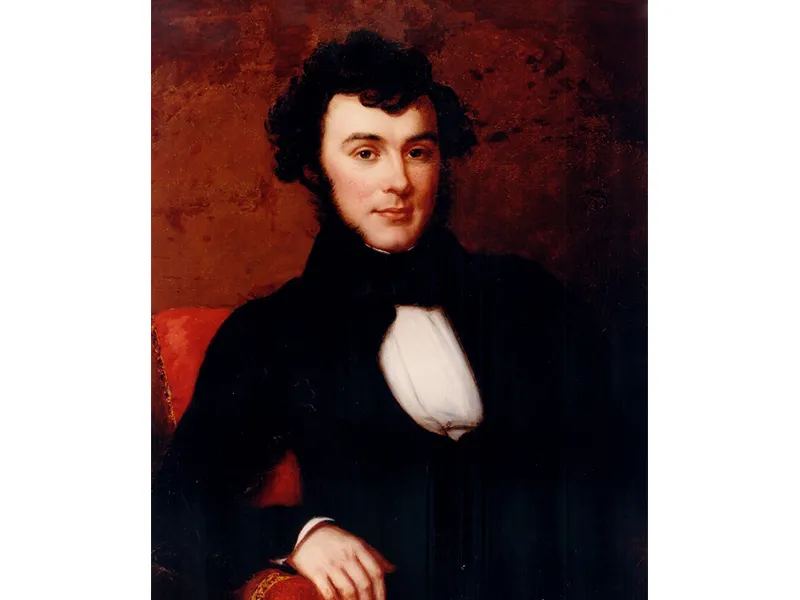

While John Quincy Adams, the first-born son of John Adams, was a stratospheric success—before becoming president in 1824, he served two terms as James Monroe’s secretary of state—his eldest son, George Washington Adams, committed suicide a month after the end of his presidency, drowning himself in the Long Island Sound while sailing from Providence to Washington. George, who had worked in Daniel Webster’s Boston law office for a few years, had recently fathered an out-of-wedlock child with a chambermaid. Due to his deep depression, he often spent his days locked in his tiny room where he “lived like a pig,” as one of his brothers put it. After learning of his son’s death, the devastated former president vowed to God to “employ the remaining days which thou has allotted me on earth to purposes…tributary to the well-being of others.” A year later, John Quincy would stage a remarkable comeback as an abolitionist Congressman.

Due to his recklessness, John Tyler, Jr., the third of President John Tyler’s eight children with his first wife, was a constant embarrassment to the family. A year after Vice President Tyler succeeded William Henry Harrison, the married John Jr. made a pass at Julia Gardiner, the Long Island beauty who would become his father’s second wife a couple of years later. Tyler ended up firing John Jr., who was then serving as his personal secretary. “The P. [President] says he really believes [John Jr.] part a madman,” Julia wrote. After the Civil War, John Jr. subsisted on a string of lowly patronage posts. “It were better,” concluded a journalist upon his death in 1896, “to be buried alive than to live a life so useless.”

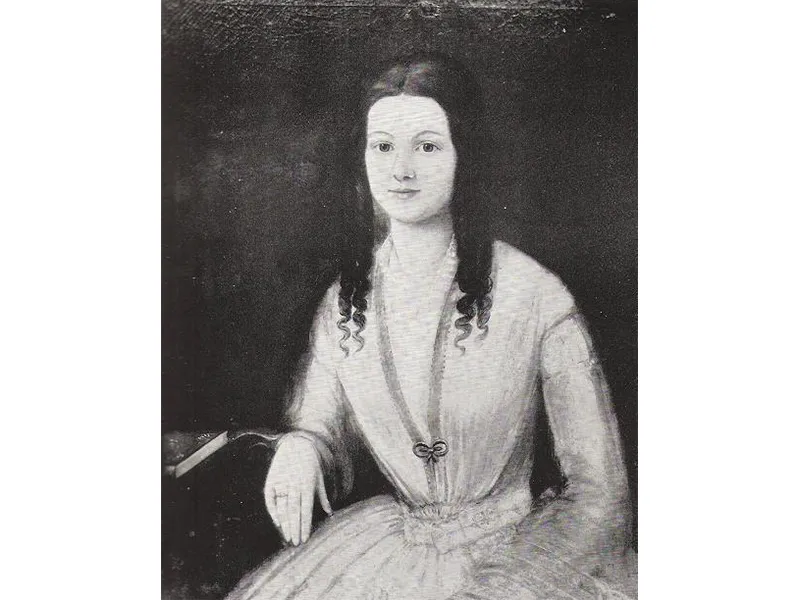

Born in the Army base in Fort Knox, Kentucky in 1814, Sarah Taylor was nicknamed “Knox” by her father, Zachary Taylor, the career military man who was elected president in 1848. At eighteen, she fell in love with Jefferson Davis—then a recent West Point graduate stationed in Wisconsin. Her father opposed the union, saying, “I’ll be damned if another daughter of mine shall marry into the army. I know enough of the family life of officers. I scarcely know my own children, or they me.” Despite his objections, she married the future president of the Confederacy in 1835. Three months after the wedding, Knox, who had moved to Louisiana with her husband, died of malaria at the age of 21.

In January of 1853, two months before his inauguration, Franklin Pierce, along his wife Jane and his third and only surviving child Benny, boarded a train in Andover, Massachusetts, which crashed soon after it left the station. The 11 year old died instantly. “Gen. Pierce took him up,” the New York Times reported, “he did not think the little boy was dead until he took off his cap.”

The Pierces were never the same. “How shall I be able to summon my manhood to gather up my energies for the duties before me, it is hard for me to see,” the devastated president-elect wrote to a friend that month. The First Lady hardly ever appeared in public and spent hours writing letters to her dead son. The loss of Benny affected the nation, as Pierce’s rudderless administration did little to stop America from heading toward a bloody internecine conflict.

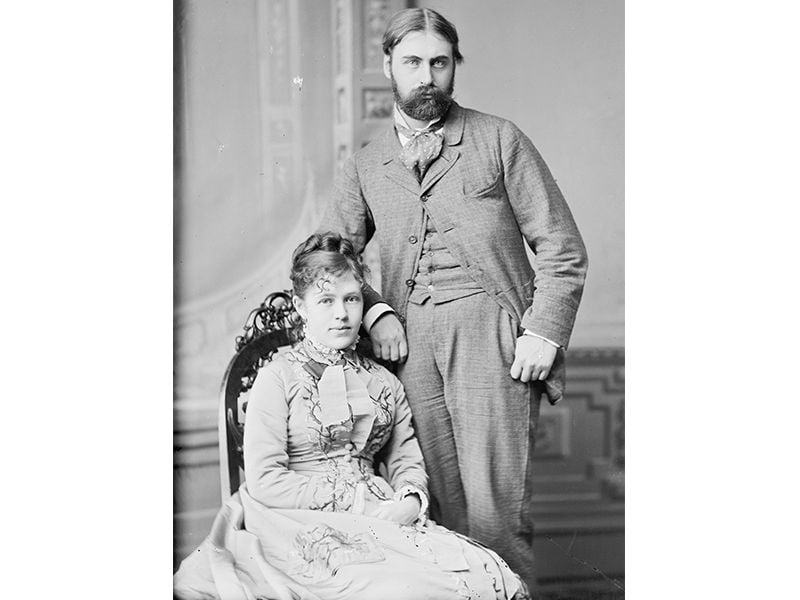

In May of 1874, 18 year-old Nellie Grant, the only daughter of President Ulysses S. Grant married Englishman Algernon Sartoris in a lavish East Room ceremony. The president was reluctant to approve the union because this minor aristocrat would be taking her back to his native land. “I yielded consent,” Grant stated, “but with a wounded heart.” His fears were well grounded. As Henry James would later put it, Sartoris was a “drunken idiot of a husband,” who often abandoned Nellie and their three children by carrying on affairs with other women all over the globe. After Sartoris’s death a decade later, the miserable Nellie moved into her mother’s home in Washington. Soon after her second marriage in 1912, Nellie suffered a stroke, which left her paralyzed for the last seven years of her life.

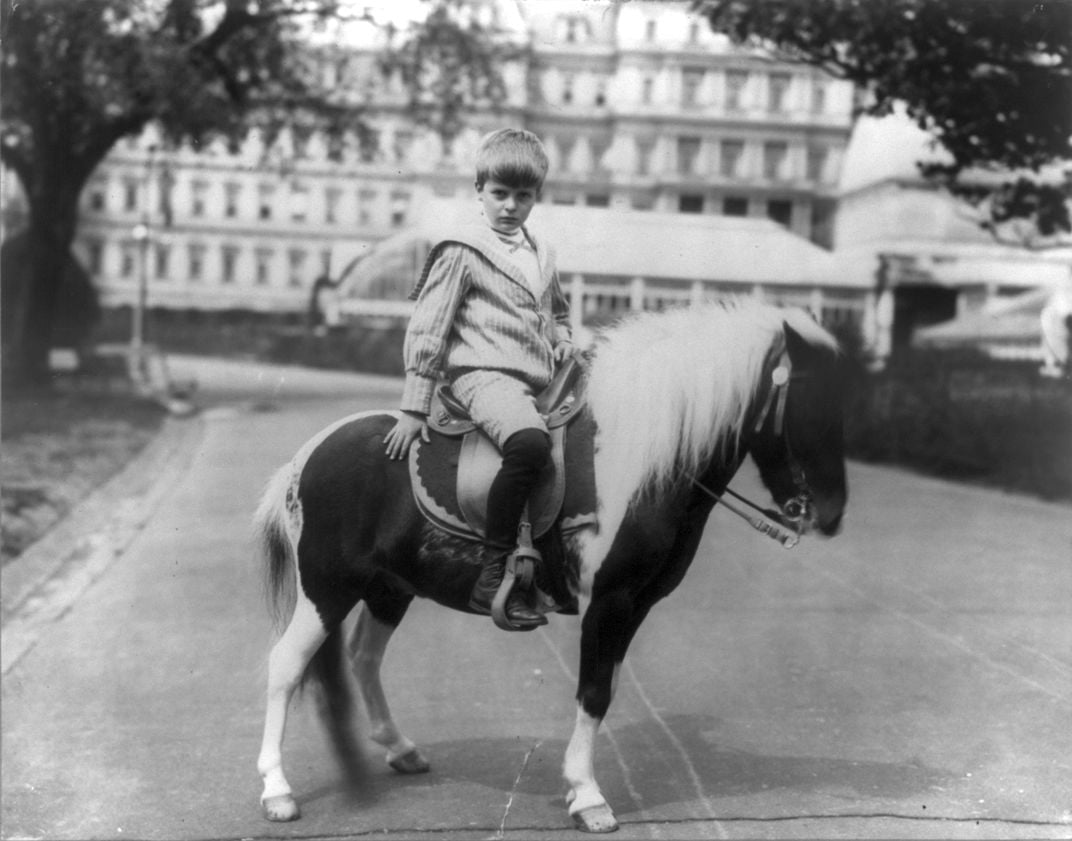

Theodore Roosevelt’s eldest child, Alice, evolved into a vibrant Washington socialite who hobnobbed with presidents until her death at 96. But his four sons, all of whom served heroically in the armed forces, fared much less well. After fighting in both Mesopotamia against the Turks and in France against the Germans in World War I, TR’s second son, Kermit, ran the Roosevelt Steamship Company. A decade later, however, he succumbed to alcoholism and depression—afflictions for which his elder brother, Archie, had sent him to a mental hospital. Though Kermit was over 50 when World War II started, he was still eager to return to the battlefield. Fully aware of Kermit’s frail health, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall sent him to a post in Alaska where he was unlikely to do any fighting. In June of 1943, Kermit shot himself in the head “due to despondence resulting from exclusion from combat duties.”

Of his six children, Theodore Roosevelt felt closest to Quentin, his youngest, who was born in 1898. Of the avid reader and natural athlete, TR once remarked, “There is something very Theodore about all this.” Like his three older brothers, Quentin jumped at the chance to serve in World War I. In the spring of 1917, after finishing his sophomore year at Harvard, Quentin headed to France. A year later, he saw action as a fighter pilot. On July 14, 1918, the Germans shot him down. The former president was crushed. “Since Quentin’s death,” TR said in the fall of 1918, “the world seems to have shut down upon me.” The heart-broken former president died a few months later.

The eldest of Woodrow Wilson’s three daughters, Margaret Wilson had a delicate constitution. “She has been a nervous child her whole life and is evidently unfitted by temperament to take a full college course,” her mother, Ellen Wilson, wrote to the Dean of Goucher College, which Margaret left after two years. After Wilson became president in 1913, Margaret took voice lessons to become a professional lieder singer. In 1918, after spending several months entertaining the troops in France, she suffered a nervous breakdown, which ended her performing career. For most of the 1920s, Margaret, who never married or found another vocation, was a lost soul. In fact, in the last year of her father’s presidency, she was almost kicked off the Fifth Avenue bus because she did not have the dime fare. (A sympathetic driver, who had no idea who she was, decided to lend her the fare.) A decade later, she discovered Hindu philosophy and went to live in an ashram in South India where she died of uremia.