Fort Sumter: The Civil War Begins

Nearly a century of discord between North and South finally exploded in April 1861 with the bombardment of Fort Sumter

:focal(1424x726:1425x727)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/43/2543305d-7b54-484a-9f02-e256a1cfd1bb/fortsumter2009.jpg)

On the afternoon of April 11, 1861, a small open boat flying a white flag pushed off from the tip of the narrow peninsula surrounding the city of Charleston. The vessel carried three envoys representing the Confederate States government, established in Montgomery, Alabama, two months before. Slaves rowed the passengers the nearly three and a half miles across the harbor to the looming hulk of Fort Sumter, where Lt. Jefferson C. Davis of the U.S. Army—no relation to the newly installed president of the Confederacy—met the arriving delegation. Davis led the envoys to the fort’s commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, who had been holed up there since just after Christmas with a tiny garrison of 87 officers and enlisted men—the last precarious symbol of federal power in passionately secessionist South Carolina.

The Confederates demanded immediate evacuation of the fort. However, they promised safe transport out of Charleston for Anderson and his men, who would be permitted to carry their weapons and personal property and to salute the Stars and Stripes, which, the Confederates acknowledged, “You have upheld so long...under the most trying circumstances.” Anderson thanked them for such “fair, manly, and courteous terms.” Yet he stated, “It is a demand with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligation to my Government, prevent my compliance.” Anderson added grimly that he would be starved out in a few days—if the Confederate cannonthat ringed the harbor didn’t batter him to pieces first. As the envoys departed and the sound of their oars faded away across the gunmetal-gray water, Anderson knew that civil war was probably only hours away.

One hundred and fifty years later, that war’s profound implications still reverberate within American hearts, heads and politics, from the lingering consequences of slavery for African-Americans to renewed debates over states’ rights and calls for the “nullification” of federal laws. Many in the South have viewed secession a matter of honor and the desire to protect a cherished way of life.

But the war was unarguably about the survival of the United States as a nation. Many believed that if secession succeeded, it would enable other sections of the country to break from the Union for any reason. “The Civil War proved that a republic could survive,” says historian Allen Guelzo of Gettysburg College. “Europe’s despots had long asserted that republics were automatically fated either to succumb to external attack or to disintegrate from within. The Revolution had proved that we could defend ourselves against outside attack. Then we proved, in the creation of the Constitution, that we could write rules for ourselves. Now the third test had come: whether a republic could defend itself against internal collapse.”

Generations of historians have argued over the cause of the war. “Everyone knew at the time that the war was ultimately about slavery,” says Orville Vernon Burton, a native South Carolinian and author of The Age of Lincoln. “After the war, some began saying that it was really about states’ rights, or a clash of two different cultures, or about the tariff, or about the industrializing North versus the agrarian South. All these interpretations came together to portray the Civil War as a collision of two noble civilizations from which black slaves had been airbrushed out.” African-American historians from W.E.B. Du Bois to John Hope Franklin begged to differ with the revisionist view, but they were overwhelmed by white historians, both Southern and Northern, who, during the long era of Jim Crow, largely ignored the importance of slavery in shaping the politics of secession.

Fifty years ago, the question of slavery was so loaded, says Harold Holzer, author of Lincoln President-Elect and other works on the 16th president, that the issue virtually paralyzed the federal commission charged with organizing events commemorating the war’s centennial in 1961, from which African-Americans were virtually excluded. (Arrangements for the sesquicentennial have been left to individual states.) At the time, some Southern members reacted with hostility to any emphasis on slavery, for fear that it would embolden the then-burgeoning civil rights movement. Only later were African-American views of the war and its origins finally heard, and scholarly opinion began to shift. Says Holzer, “Only in recent years have we returned to the obvious—that it was about slavery.”

As Emory Thomas, author of The Confederate Nation 1861-1865 and a retired professor of history at the University of Georgia, puts it, “The heart and soul of the secession argument was slavery and race. Most white Southerners favored racial subordination, and they wanted to protect the status quo. They were concerned that the Lincoln administration would restrict slavery, and they were right.”

Of course, in the spring of 1861, no one could foresee either the four-year-long war’s numbing human cost, or its outcome. Many Southerners assumed that secession could be accomplished peacefully, while many Northerners thought that a little saber rattling would be sufficient to bring the rebels to their senses. Both sides, of course, were fatally wrong. “The war would produce a new nation, very different in 1865 from what it had been in 1860,” says Thomas. The war was a conflict of epic dimensions that cost 620,000 American lives, and brought about a racial and economic revolution, fundamentally altering the South’s cotton economy and transforming four million slaves from chattel into soldiers, citizens and eventually national leaders.

The road to secession had begun with the nation’s founding, at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which attempted to square the libertarian ideals of the American Revolution with the fact that human beings were held in bondage. Over time, the Southern states would grow increasingly determined to protect their slave-based economies. The founding fathers agreed to accommodate slavery by granting slave states additional representation in Congress, based on a formula that counted three-fifths of their enslaved population. Optimists believed that slavery, a practice that was becoming increasingly costly, would disappear naturally, and with it electoral distortion. Instead, the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 spurred production of the crop and with it, slavery. There were nearly 900,000 enslaved Americans in 1800. By 1860, there were four million—and the number of slave states increased accordingly, fueling a sense of impending national crisis over the South’s “peculiar institution.”

A crisis had occurred in 1819, when Southerners had threatened secession to protect slavery. The Missouri Compromise the next year, however, calmed the waters. Under its provisions, Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state, while Maine would be admitted as a free state. And, it was agreed, future territories north of a boundary line within land acquired by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 would be free of slavery. The South was guaranteed parity in the U.S. Senate—even as population growth in the free states had eroded the South’s advantages in the House of Representatives. In 1850, when the admission of gold-rich California finally tipped the balance of free states in the Senate in the North’s favor, Congress, as a concession to the South, passed the Fugitive Slave Law, which required citizens of Northern states to collaborate with slave hunters in capturing fugitive slaves. But it had already become clear to many Southern leaders that secession in defense of slavery was only a matter of time.

Sectional strife accelerated through the 1850s. In the North, the Fugitive Slave Law radicalized even apathetic Yankees. “Northerners didn’t want anything to do with slavery,” says historian Bernard Powers of the College of Charleston. “The law shocked them when they realized that they could be compelled to arrest fugitive slaves in their own states, that they were being dragged kicking and screaming into entanglement with slavery.” In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act further jolted Northerners by opening to slavery western territories that they had expected would remain forever free.

By late the next year, the Kansas Territory erupted into guerrilla warfare between pro-slavery and antislavery forces; the violence would leave more than 50 dead. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 further inflamed Northerners by declaring, in effect, that free-state laws barring slavery from their own soil were essentially superseded. The decision threatened to make slavery a national institution. John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, in October 1859, seemed to vindicate slave owners’ long-standing fear that abolitionists intended to invade the South and liberate their slaves by force. In 1858, Abraham Lincoln, declaring his candidacy for the Senate, succinctly characterized the dilemma: “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.”

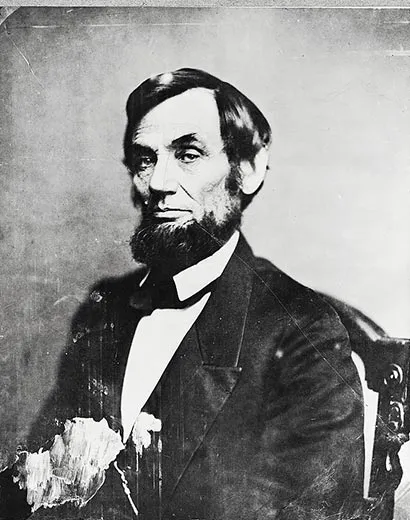

For the South, the last straw was Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, with only 39.8 percent of the vote. In a four-way contest against Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, Constitutional Unionist John Bell and the South’s favorite son, Kentucky Democrat John Breckenridge, Lincoln received not a single electoral vote south of the Mason-Dixon line. In her diary, Charleston socialite Mary Boykin Chesnut recounted the reaction she had overheard on a train when news of Lincoln’s election was announced. One passenger, she recalled, had exclaimed: “Now that...radical Republicans have the power I suppose they will [John] Brown us all.”Although Lincoln hated slavery, he was far from an abolitionist; he believed freed blacks should be sent to Africa or Central America, and declared explicitly that he would not tamper with slavery where it already existed. (He did make clear that he would oppose the expansion of slavery into new territories.)

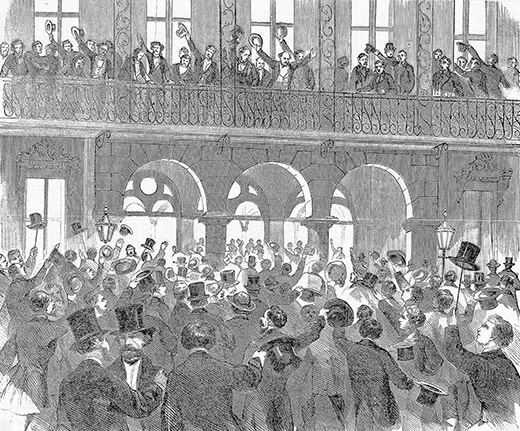

However, the so-called Fire-eaters, the most radical Southern nationalists who dominated Southern politics, were no longer interested in compromise. “South Carolina will secede from the Union as surely as that night succeeds the day, and nothing can now prevent or delay it but a revolution at the North,” South Carolinian William Trenholm wrote to a friend. “The...Republican party, inflamed by fanaticism and blinded by arrogance, have leapt into the pit which a just Providence prepared for them.” In Charleston, cannon were fired, martial music was played, flags were waved in every street. Men young and old flocked to join militia companies. Even children delivered “resistance speeches” to their playmates and strutted the lanes with homemade banners.

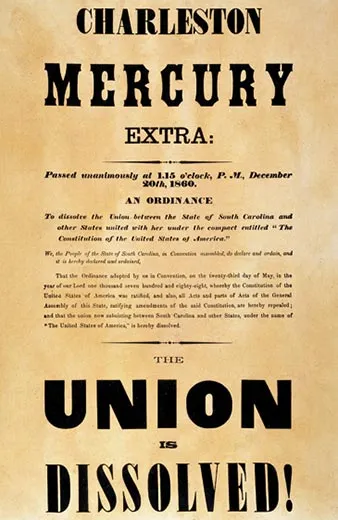

In December 1860, a little more than a month after Lincoln’s election, South Carolina’s secession convention, held in Charleston, called on the South to join “a great Slaveholding Confederacy, stretching its arms over a territory larger than any power in Europe possesses.” While most Southerners did not own slaves, slave owners wielded power far beyond their numbers: more than 90 percent of the secessionist conventioneers were slaveholders. In breaking up the Union, the South Carolinians claimed, they were but following the founding fathers, who had established the United States as a “union of slaveholding States.” They added that a government dominated by the North must sooner or later lead to emancipation, no matter what the North claimed. Delegates flooded into the streets, shouting, “We are afloat!” as church bells rang, bonfires roared and fireworks shot through the sky.

By 1861, Charleston had witnessed economic decline for decades. Renowned for its residents’ genteel manners and its gracious architecture, the city was rather like a “distressed elderly gentlewoman....a little gone down in the world, yet remembering still its former dignity,” as one visitor put it. It was a cosmopolitan city, with significant minorities of French, Jews, Irish, Germans—and some 17,000 blacks (82 percent of them slaves), who made up 43 percent of the total population. Charleston had been a center of the slave trade since colonial times, and some 40 slave traders operated within a two-square-block area. Even as white Charlestonians boasted publicly of their slaves’ loyalty, they lived in fear of an uprising that would slaughter them in their beds. “People talk before [slaves] as if they were chairs and tables,” Mary Chesnut wrote in her diary. “They make no sign. Are they stolidly stupid? or wiser than we are; silent and strong, biding their time?”

According to historian Douglas R. Egerton, author of Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election that Brought on the Civil War, “To win over the yeoman farmers—who would wind up doing nearly all the fighting—the Fire-eaters relentlessly played on race, warning them that, unless they supported secession, within ten years or less their children would be the slaves of Negroes.”

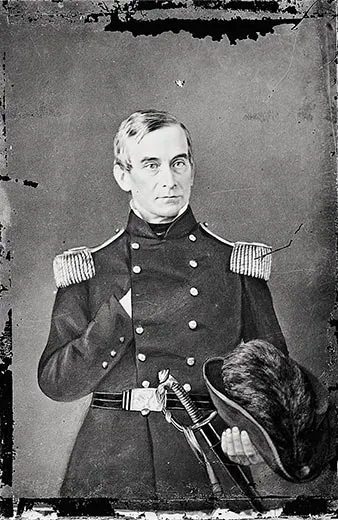

Despite its decline, Charleston remained the Confederacy’s most important port on the Southeast coast. The spectacular harbor was defended by three federal forts: Sumter; tiny Castle Pinckney, one mile off the city’s Battery; and heavily armed Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island, where Major Anderson’s command was based but where its guns pointed out to sea, making it defenseless from land.

On December 27, a week after South Carolina’s declaration of secession, Charlestonians awoke to discover that Anderson and his men had slipped away from Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. For secessionists, Anderson’s move “was like casting a spark into a magazine,” wrote one Charlestonian, T. W. Moore, to a friend. Although a military setback for Confederates, who had expected to muscle the federal troops out of Moultrie, Anderson’s move enabled the Fire-eaters to blame Washington for “defying” South Carolina’s peaceable efforts to secede.

Fort Sumter had been planned in the 1820s as a bastion of coastal defense, with its five sides, an interior large enough to house 650 defenders and 135 guns commanding the shipping channels to Charleston Harbor. Construction, however, had never been completed. Only 15 cannon had been mounted; the interior of the fort was a construction site, with guns, carriages, stone and other materials stacked about. Its five-foot-thick brick walls had been designed to withstand any cannonballs that might be hurled—by the navies of the 1820s, according to Rick Hatcher, the National Park Service historian at the fort. Although no one knew it at the time, Fort Sumter was already obsolete. Even conventional guns pointed at the fort could lob cannonballs that would destroy brick and mortar with repeated pounding.

Anderson’s men hailed from Ireland, Germany, England, Denmark and Sweden. His force included native-born Americans as well. The garrison was secure against infantry attack but almost totally isolated from the outside world. Conditions were bleak. Food, mattresses and blankets were in short supply. From their thick-walled casements, the gunners could see Charleston’s steeples and the ring of islands where gangs of slaves and soldiers were already erecting bastions to protect the Southern artillery.

Militiamen itching for a fight flooded into Charleston from the surrounding countryside. There would soon be more than 3,000 of them facing Fort Sumter, commanded by the preening and punctilious Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, who had resigned his position as West Point’s superintendent to offer his services to the Confederacy.

“To prove it was a country, the South had to prove that it had sovereignty over its territory,” says historian Allen Guelzo. “Otherwise no one, especially the Europeans, would take them seriously. Sumter was like a huge flag in the middle of Charleston Harbor that declared, in effect, ‘You don’t have the sovereignty that you claim.’ ”

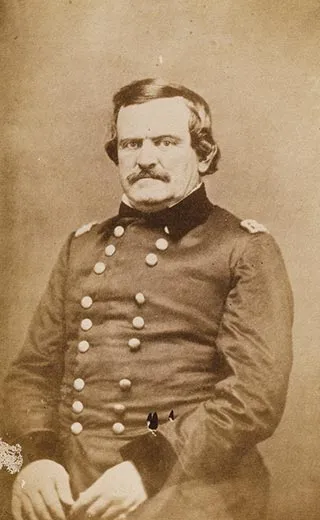

With communications from his superiors reaching him only sporadically, Anderson was entrusted with heavy responsibilities. Although Kentucky born and bred, his loyalty to the Union was unshakeable. In the months to come, his second-in-command, Capt. Abner Doubleday—a New York abolitionist, and the man who was long credited, incorrectly, with inventing baseball—would express frustration at Anderson’s “inaction.” “I have no doubt he thought he was rendering a real service to the country,” Doubleday later wrote. “He knew the first shot fired by us would light the flames of a civil war that would convulse the world, and tried to put off the evil day as long as possible. Yet a better analysis of the situation might have taught him that the contest had already commenced and could no longer be avoided.” But Anderson was a good choice for the role that befell him. “He was both a seasoned soldier and a diplomat,” says Hatcher. “He would do just about anything he could to avoid war. He showed tremendous restraint.”

Anderson’s distant commander in chief was the lame-duck president, Democrat James Buchanan, who passively maintained that while he believed secession to be illegal, there was nothing he could do about it. A Northerner with Southern sympathies, Buchanan had spent his long career accommodating the South, even to the point of allowing South Carolina to seize all the other federal properties in the state. For months, as the crisis deepened, Buchanan had vacillated. Finally, in January, he dispatched a paddle wheel steamer, Star of the West, carrying a cargo of provisions and 200 reinforcements for the Sumter garrison. But when Confederate batteries fired on her at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, the ship’s skipper turned the ship around and fled north, leaving Anderson’s men to their fate. This ignominious expedition represented Buchanan’s only attempt to assert federal power in the waters off Charleston.

Some were convinced the Union was finished. The British vice-consul in Charleston, H. Pinckney Walker, saw the government’s failure to resupply Fort Sumter as proof of its impotence. He predicted the North would splinter into two or three more republics, putting an end to the United States forever. The Confederacy, he wrote, formed what he called “a very nice little plantation” that could look forward to “a career of prosperity such as the world has not before known.” Popular sentiment in Charleston was reflected in the ardently secessionist Charleston Mercury, which scoffed that federal power was “a wretched humbug—a scarecrow—a dirty bundle of red rags and old clothes” and Yankee soldiers just “poor hirelings” who would never fight. The paper dismissed Lincoln as a “vain, ignorant, low fellow.”

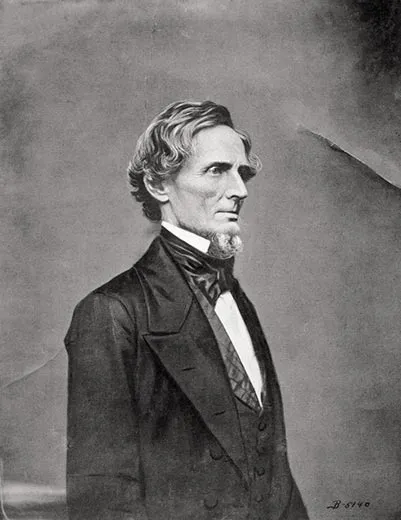

While Buchanan dithered, six more states seceded: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. On February 4, the Confederate States of America declared its independence in Montgomery, Alabama, and named Mexican War hero, former Secretary of War and senator from Mississippi Jefferson Davis, its president. “The radicals felt they were making a revolution, like Tom Paine and Samuel Adams,” says Emory Thomas. Although Davis had long argued for the right of secession, when it finally came he was one of few Confederate leaders who recognized that it would probably mean a long and bloody war. Southern senators and congressmen resigned and headed south.

Secessionists occupied federal forts, arsenals and customhouses from Charleston to Galveston, while in Texas, David Twiggs, commander of federal forces there, surrendered his troops to the state militia and joined the Confederate Army. Soon the only significant Southern posts that remained in federal hands were Fort Sumter and Florida’s Fort Pickens, at the entrance to Pensacola Harbor. “The tide of secession was overpowering,” says Thomas. “It was like the moment after Pearl Harbor—people were ready to go to war.” Buchanan now wanted nothing more than to dump the whole mess in Lincoln’s lap and retire to the quietude of his estate in Pennsylvania. But Lincoln would not take office until March 4. (Not until 1933 was Inauguration Day moved up to January 20.)

The new president who slipped quietly into Washington on February 23, forced to keep a low profile because of credible death threats, was convinced that war could still be avoided. “Lincoln had been a compromiser his whole life,” says Orville Vernon Burton. “He was naturally flexible: as a lawyer, he had always invited people to settle out of court. He was willing to live with slavery where it already was. But when it came to the honor of the United States, there was a point beyond which he wouldn’t go.”

Once in office, Lincoln entered into a high-stakes strategic gamble that was all but invisible to the isolated garrison at Fort Sumter. It was in the Confederacy’s interest to provoke a confrontation that made Lincoln appear the aggressor. Lincoln and his advisers believed, however, that secessionist sentiment, red-hot in the Deep South, was only lukewarm in the Upper South states of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas, and weaker yet in the four slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. Conservatives, including Secretary of State William H. Seward, urged the president to appease the Deep South and evacuate the fort, in hopes of keeping the remaining slave states in the Union. But Lincoln knew that if he did so, he would lose the confidence of both the Republican Party and most of the North.

“He had such faith in the idea of Union that he hoped that [moderates] in the Upper South would never let their states secede,” says Harold Holzer. “He was also one of the great brinksmen of all time.” Although Lincoln was committed to retaking federal forts occupied by the rebels and to defending those still in government hands, he indicated to a delegation from Richmond that if they kept Virginia in the Union, he would consider relinquishing Sumter to South Carolina. At the same time, he reasoned that the longer the standoff over Fort Sumter continued, the weaker the secessionists—and the stronger the federal government—would look.

Lincoln initially “believed that if he didn’t allow the South to provoke him, war could be avoided,” says Burton. “He also thought they wouldn’t really fire on Fort Sumter.” Because negotiating directly with Jefferson Davis would have implied recognition of the Confederacy, Lincoln communicated only with South Carolina’s secessionist—but nonetheless duly elected—governor, Francis Pickens. Lincoln made clear that he intended to dispatch vessels carrying supplies and reinforcements to Fort Sumter: if the rebels fired on them, he warned, he was prepared to land troops to enforce the federal government’s authority.

Rumors flew in every direction: a federal army was set to invade Texas...the British and French would intervene...Northern businessmen would come out en masse against war. In Charleston, the mood fluctuated between overwrought excitement and dread. By the end of March, after three cold, damp months camped on the sand dunes and snake-infested islands around Charleston Harbor, Fort Sumter’s attackers were growing feverishly impatient. “It requires all the wisdom of their superiors to keep them cool,” wrote Caroline Gilman, a transplanted Northerner who had embraced the secessionist cause.

For a month after his inauguration, Lincoln weighed the political cost of relieving Fort Sumter. On April 4, he came to a decision. He ordered a small flotilla of vessels, led by Navy Capt. Gustavus Vasa Fox, to sail from New York, carrying supplies and 200 reinforcements to the fort. He refrained from sending a full-scale fleet of warships. Lincoln may have concluded that war was inevitable, and it would serve the federal government’s interest to cause the rebels to fire the first shot.

The South Carolinians had made clear that any attempt to reinforce Sumter would mean war. “Now the issue of battle is to be forced upon us,” declared the Charleston Mercury. “We will meet the invader, and the God of Battles must decide the issue between the hostile hirelings of Abolition hate and Northern tyranny.”

“How can one settle down to anything? One’s heart is in one’s mouth all the time,” Mary Chesnut wrote in her diary. “The air is red-hot with rumors.” To break the tension on occasion, Chesnut crept to her room and wept. Her friend Charlotte Wigfall warned, “The slave-owners must expect a servile insurrection.”

In the early hours of April 12, approximately nine hours after the Confederates had first asked Anderson to evacuate Fort Sumter, the envoys were again rowed out to the garrison. They made an offer: if Anderson would state when he and his men intended to quit the fort, the Confederates would hold their fire. Anderson called a council of his officers: How long could they hold out? Five days at most, he was told, which meant three days with virtually no food. Although the men had managed to mount about 45 cannon, in addition to the original 15, not all of those could be trained on Confederate positions. Even so, every man at the table voted to reject immediate surrender to the Confederates.

Anderson sent back a message to the Confederate authorities, informing them that he would evacuate the fort, but not until noon on the 15th, adding, “I will not in the meantime open my fire upon your forces unless compelled to do so by some hostile act against this fort or the flag of my Government.”

But the Confederacy would tolerate no further delay. The envoys immediately handed Anderson a statement: “Sir: By authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard, commanding the provisional forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.”

Anderson roused his men, informing them an attack was imminent. At 4:30 a.m., the heavy thud of a mortar broke the stillness. A single shell from Fort Johnson on James Island rose high into the still-starry sky, curved downward and burst directly over Fort Sumter. Confederate batteries on Morris Island opened up, then others from Sullivan’s Island, until Sumter was surrounded by a ring of fire. As geysers of brick and mortar spumed up where balls hit the ramparts, shouts of triumph rang from the rebel emplacements. In Charleston, families by the thousands rushed to rooftops, balconies and down to the waterfront to witness what the Charleston Mercury would describe as a “Splendid Pyrotechnic Exhibition.”

To conserve powder cartridges, the garrison endured the bombardment without reply for two and a half hours. At 7 a.m., Anderson directed Doubleday to return fire from about 20 guns, roughly one half as many as the Confederates. The Union volley sent vast flocks of water birds rocketing skyward from the surrounding marsh.

At about 10 a.m., Capt. Truman Seymour replaced Doubleday’s exhausted crew with a fresh detachment.

“Doubleday, what in the world is the matter here, and what is all this uproar about?” Seymour inquired dryly.

“There is a trifling difference of opinion between us and our neighbors opposite, and we are trying to settle it,” the New Yorker replied.

“Very well,” said Seymour, with mock graciousness. “Do you wish me to take a hand?”

“Yes,” Doubleday responded. “I would like to have you go in.”

At Fort Moultrie, now occupied by the Confederates, federal shots hit bales of cotton that rebel gunners were using as bulwarks. At each detonation, the rebels gleefully shouted, “Cotton is falling!” And when a shot exploded the kitchen, blowing loaves of bread into the air, they cried, “Breadstuffs are rising!”

Humor was less on display in the aristocratic homes of Charleston, where the roar of artillery began to rattle even the most devout secessionists. “Some of the anxious hearts lie on their beds and moan in solitary misery,” trying to reassure themselves that God was really on the Confederate side, recorded Chesnut.

At the height of the bombardment, Fox’s relief flotilla at last hove into sight from the north. To the federals’ dismay, however, Fox’s ships continued to wait off the coast, beyond range of rebel guns: their captains hadn’t bargained on finding themselves in the middle of an artillery duel. The sight of reinforcements so tantalizingly close was maddening to those on Sumter. But even Doubleday admitted that had the ships tried to enter the harbor, “this course would probably have resulted in the sinking of every vessel.”

The bombardment slackened during the rainy night but kept on at 15-minute intervals, and began again in earnest at 4 a.m. on the 13th. Roaring flames, dense masses of swirling smoke, exploding shells and the sound of falling masonry “made the fort a pandemonium,” recalled Doubleday. Wind drove smoke into the already claustrophobic casements, where Anderson’s gunners nearly suffocated. “Some lay down close to the ground, with handkerchiefs over their mouths, and others posted themselves near the embrasures, where the smoke was somewhat lessened by the draught of air,” recalled Doubleday. “Everyone suffered severely.”

At 1:30 p.m., the fort’s flagstaff was shot away, although the flag itself was soon reattached to a short spar and raised on the parapet, much to the disappointment of rebel marksmen. As fires crept toward the powder magazine, soldiers raced to remove hundreds of barrels of powder that threatened to blow the garrison into the cloudless sky. As the supply of cartridges steadily shrank, Sumter’s guns fell silent one by one.

Soon after the flagpole fell, Louis Wigfall, husband of Charlotte Wigfall and a former U.S. senator from Texas now serving under Beauregard, had himself rowed to the fort under a white flag to call again for Anderson’s surrender. The grandstanding Wigfall had no formal authority to negotiate, but he offered Anderson the same terms that Beauregard had offered a few days earlier: Anderson would be allowed to evacuate his command with dignity, arms in hand, and be given unimpeded transport to the North and permission to salute the Stars and Stripes.

“Instead of noon on the 15th, I will go now,” Anderson quietly replied. He had made his stand. He had virtually no powder cartridges left. His brave, hopelessly outgunned band of men had defended the national honor with their lives without respite for 34 hours. The outcome was not in question.

“Then the fort is to be ours?” Wig-fall eagerly inquired.

Anderson ordered a white flag to be raised. Firing from rebel batteries ceased.

The agreement nearly collapsed when three Confederate officers showed up to request a surrender. Anderson was so furious at having capitulated to the freelancing Wigfall that he was about to run up the flag yet again. However, he was persuaded to wait until confirmation of the terms of surrender, which arrived soon afterward from Beauregard.

When news of the surrender at last reached the besieging rebels, they vaulted onto the sand hills and cheered wildly; a horseman galloped at full speed along the beach at Morris Island, waving his cap and exulting at the tidings.

Fort Sumter lay in ruins. Flames smoldered amid the shot-pocked battlements, dismounted cannon and charred gun carriages. Astoundingly, despite an estimated 3,000 cannon shots fired at the fort, not a single soldier had been killed on either side. Only a handful of the fort’s defenders had even been injured by fragments of concrete and mortar.

Beauregard had agreed to permit the defenders to salute the U.S. flag before they departed. The next afternoon, Sunday, April 14, Fort Sumter’s remaining artillery began a rolling cannonade of what was meant to total 100 guns. Tragically, however, one cannon fired prematurely and blew off the right arm of a gunner, Pvt. Daniel Hough, killing him almost instantly and fatally wounding another Union soldier. The two men thus became the first fatalities of the Civil War.

At 4:30 p.m., Anderson handed over control of the fort to the South Carolina militia. The exhausted, blue-clad Union soldiers stood in formation on what remained of the parade ground, with flags flying and drums beating out the tune of “Yankee Doodle.” Within minutes, the flags of the Confederacy and South Carolina were snapping over the blasted ramparts. “Wonderful, miraculous, unheard of in history, a bloodless victory!” exclaimed Caroline Gilman in a letter to one of her daughters.

A steamboat lent by a local businessman carried Anderson’s battle-weary band out to the federal fleet, past hordes of joyful Charlestonians gathered on steamers, sailboats bobbing rowboats and dinghies, under the eyes of rebel soldiers poised silently on the shore, their heads bared in an unexpected gesture of respect. Physically and emotionally drained, and halfway starved, Anderson and his men gazed back toward the fort where they had made grim history. In their future lay the slaughter pens of Bull Run, Shiloh, Antie-tam, Gettysburg, Chickamauga and hundreds more still unimaginable battlefields from Virginia to Missouri. The Civil War had begun.

Fergus Bordewich’s most recent book is Washington: The Making of the American Capital. Photographer Vincent Musi is based in Charleston, South Carolina.