Fred Birchmore’s Amazing Bicycle Trip Around the World

The American cyclist crossed paths with Sonja Henje and Adolf Hitler as he transversed the globe on Bucephalus, his trusty bike

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fred-Birchmore-around-the-world-on-a-bike-631.jpg)

Fred Birchmore of Athens, Georgia, belongs to an exclusive club: he’s a round-the-world cyclist. The club’s charter member, Thomas Stevens, pedaled his high-wheeler some 15,000 miles across North America, Europe and Asia between 1884 and 1887. Mark Beaumont of Scotland set the current world record in 2007-08, covering almost 18,300 miles in 194 days and 17 hours.

Birchmore finished his epic two-year, 25,000-mile crossing of Eurasia 75 years ago this October. (North America came later.) And unlike the American Frank Lenz, who became famous after he disappeared in Turkey while trying to top Stevens’ feat in 1894, Birchmore lived to tell of his journey. He will turn 100 on November 29.

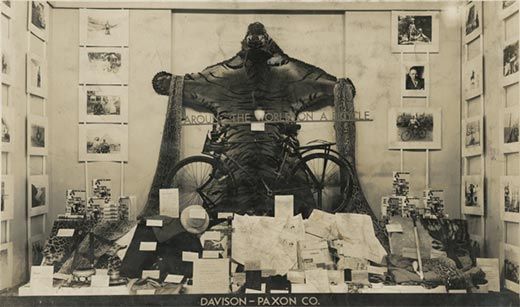

Birchmore got his first look at Europe from a bicycle seat in the summer of 1935, shortly after he earned a law degree from the University of Georgia. He was on his way to the University of Cologne to study international law when he stopped in central Germany and bought a bicycle: a one-speed, 42-pound Reinhardt. (It is in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.) He named it Bucephalus, after Alexander the Great’s horse. Before his classes started, he toured northern Europe with a German friend and Italy, France and Britain by himself.

“I had some wonderful experiences that had nothing to do with the bicycle,” Birchmore recalled in a recent interview at Happy Hollow, his Athens home, which he shares with his wife of 72 years, Willa Deane Birchmore. He cited his climb up the Matterhorn, his swim in the Blue Grotto off Capri, and his brush with the Norwegian Olympic skater and future Hollywood actress Sonja Henie. “I just happened to ice skate on the same lake where she practiced,” he said. “Well, I never had skated. I figured, ‘I’m going to break my neck.’ She came over and gave me a few pointers. Beautiful girl.”

Back in Cologne, he attended a student rally—and came face to face with Adolf Hitler. Working up the crowd, Hitler demanded to know if any Americans were present; Birchmore’s friends pushed him forward. “He nearly hit me in the eye with his ‘Heil, Hitler,’ ” the cyclist recalled. “I thought, ‘Why you little.…’ He was wild-eyed, made himself believe he was a gift from the gods.” But Birchmore kept his cool. “I looked over and there were about 25 or 30 brown-shirted guys with bayonets stuck on the end of their rifles. He gave a little speech and tried to convert me then and there.” The Führer failed.

Although he enjoyed a comfortable life as the guest of a prominent local family, Birchmore was increasingly disturbed by Nazi Germany. From his bicycle, he saw firsthand the signs of a growing militarism. “I was constantly passing soldiers, tanks, giant air fleets and artillery,” he wrote in his memoir, Around the World on a Bicycle.

In February 1936, after completing his first semester, Birchmore cycled through Yugoslavia and Greece and sailed to Cairo. After he reached Suez that March, disaster struck: while he slept on a beach, thieves made off with his cash and passport. Birchmore had to sell off some of his few possessions to pay for a third-class train ticket back to Cairo. On board, he marveled at how “great reservoirs of kindness lay hidden even in the hearts of the poorest,” he wrote. “When word passed around that I was not really one of those brain-cracked millionaires, ‘roughing it’ for the novelty, but broke like them, I was immediately showered with sincere sympathies and offers of material gifts.”

Six weeks passed before he received a new passport. He had already missed the start of the new semester. Having little incentive to return to Cologne, he decided to keep going east as far as his bike would take him. He set off for Damascus and then on to Baghdad, crossing the scorching Syrian desert in six days.

By the time he reached Tehran, he was in a bad way. An American missionary, William Miller, was shocked to find the young cyclist at the mission’s hospital, a gigantic boil on his leg. “He had lived on chocolate and had eaten no proper food so as not to make his load too heavy,” Miller marveled in his memoir, My Persian Pilgrimage. “I brought him to my house. What luxury it was to him to be able to sleep in a bed again! And when we gave him some spinach for dinner he said it was the most delicious food he had ever tasted. To the children of the mission, Fred was a great hero.”

In Afghanistan Birchmore traversed 500 rugged miles, from Herat to Bamian to Kabul, on a course largely of his own charting. Once he had to track down a village blacksmith to repair a broken pedal. “Occasionally, he passed caravans of city merchants, guarded front and rear by armed soldiers,” National Geographic would report. “Signs of automobile tire treads in the sands mystified him, until he observed that many of the shoes were soled with pieces of old rubber tires.”

While traveling along the Grand Trunk Road in India, Birchmore was struck by the number of 100-year-olds he encountered. “No wonder Indians who escape cholera and tuberculosis live so long,” he wrote. “They eat sparingly only twice a day and average fifteen hours of sleep.” (He added: “Americans eat too much, sleep too little, work too hard, and travel too fast to live to a ripe old age.”)

Birchmore’s travails culminated that summer in the dense jungles of Southeast Asia, where he tangled with tigers and cobras and came away with a hide from each species. But a mosquito got the better of him: after collapsing in the jungle, he awoke to find himself abed with a malarial fever in a Catholic missionary hospital in the village of Moglin, Burma.

After riding through Thailand and Vietnam, Birchman boarded on a rice boat to Manila with Bucephalus in tow. In early September, he set sail for San Pedro, California, aboard the SS Hanover. He expected to cycle the 3,000 miles back home to Athens, but he found his anxious parents on the dock to greet him. He and Bucephalus returned to Georgia in the family station wagon.

Nevertheless, Birchmore looked back on his trip with supreme satisfaction, feeling enriched by his exposure to so many people and lands. “Surely one can love his own country without becoming hopelessly lost in an all-consuming flame of narrow-minded nationalism,” he wrote.

Still restless, Birchmore had a hard time concentrating on legal matters. In 1939, he took a 12,000-mile bicycle tour around North America with a pal. He married Willa Deane later that year, and they honeymooned aboard a tandem bike, covering 4,500 miles in Latin America. After serving as a Navy gunner in World War II, he opened a real estate agency. He and Willa Deane raised four children, and he immersed himself in community affairs.

After he retired, in 1973, he embarked on a 4,000-mile bicycle ride through Europe with Danny, the youngest of his children. Two years later, they hiked the 2,000 miles of the Appalachian Trail. While in his 70s, he hand-built a massive stone wall around Happy Hollow. He cycled into his 90s, and he still rides a stationary bike at the local Y. A few years ago, he told a journalist, “For me, the great purposes in life are to have as many adventures as possible, to brighten the lives of as many as possible, and to leave this old world a little bit better place.”