Frost, Nixon and Me

Author James Reston Jr. discovers firsthand what is gained and lost when history is turned into entertainment

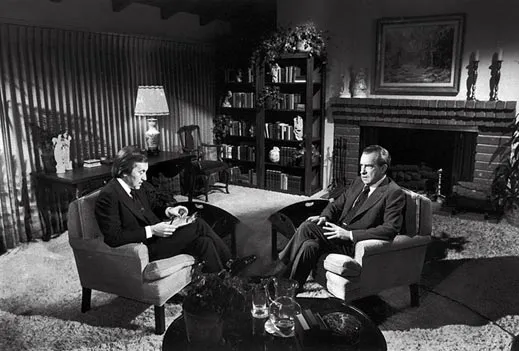

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/frost-nixon-sheen-langella-631.jpg)

In May 1976, in a rather dim New York City hotel room filled with David Frost's cigar smoke, the British television personality put an intriguing proposition to me: leave your leafy academic perch for a year and prepare me for what could be a historic interrogation of Richard Nixon about Watergate.

This would be the nation's only chance for no holds barred questioning of Nixon on the scandal that drove him to resign the presidency in 1974. Pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, Nixon could never be brought into the dock. Frost had secured the exclusive rights to interview him. Thus the prosecution of Richard Nixon would be left to a television interview by a foreigner.

I took the job.

The resulting Frost-Nixon interviews— one in particular—indeed proved historic. On May 4, 1977, forty-five million Americans watched Frost elicit a sorrowful admission from Nixon about his part in the scandal: "I let down my friends," the ex-president conceded. "I let down the country. I let down our system of government, and the dreams of all those young people that ought to get into government but now think it too corrupt....I let the American people down, and I have to carry that burden with me the rest of my life."

If that interview made both political and broadcast history, it was all but forgotten two years ago, when the Nixon interviews were radically transformed into a piece of entertainment, first as the play Frost/Nixon, and now as a Hollywood film of the same title. For that televised interview in 1977, four hours of interrogation had been boiled down to 90 minutes. For the stage and screen, this history has been compressed a great deal more, into something resembling comedic tragedy. Having participated in the original event as Frost's Watergate researcher, and having had a ringside seat at its transformation, I've been thinking a lot lately about what is gained and what is lost when history is turned into entertainment.

I had accepted Frost's offer with some reservations. Nixon was a skilled lawyer who had denied Watergate complicity for two years. He had seethed in exile. For him, the Frost interviews were a chance to persuade the American people that he had been done an epic injustice—and to make upwards of $1 million for the privilege. And in David Frost, who had no discernible political philosophy and a reputation as a soft-soap interviewer, Nixon seemed to have found the perfect instrument for his rehabilitation.

Although Nixon's active role in the coverup had been documented in a succession of official forums, the absence of a judicial prosecution had left the country with a feeling of unfinished business. To hear Nixon admit to high crimes and misdemeanors could provide a national catharsis, a closing of the books on a depressing episode of American history.

For all my reservations, I took on the assignment with gusto. I had worked on the first Watergate book to advocate impeachment. I had taken a year off from teaching creative writing at the University of North Carolina to witness the Ervin Committee hearings of 1973, from which most Americans' understanding of Watergate came, because I regarded the scandal as the greatest political drama of our time. My passion lay in my opposition to the Vietnam War, which I felt Nixon had needlessly prolonged for six bloody years; in my sympathy for Vietnam War resisters, who had been pilloried by the Nixonians; and in my horror over Watergate itself. But I was also driven by my desire for engagement and, I like to think, a novelist's sense of the dramatic.

To master the canon of Watergate was a daunting task, for the volumes of evidence from the Senate, the House and various courts would fill a small closet. Over many months I combed through the archives, and I came across new evidence of Nixon's collusion with his aide Charles Colson in the coverup—evidence that I was certain would surprise Nixon and perhaps jar him out of his studied defenses. But mastering the record was only the beginning. There had to be a strategy for compressing two years of history into 90 minutes of television. To this end, I wrote a 96-page interrogation strategy memo for Frost.

In the broadcast, the interviewer's victory seemed quick, and Nixon's admission seemed to come seamlessly. In reality, it was painfully extracted from a slow, grinding process over two days.

At my suggestion, Frost posed his questions with an assumption of guilt. When Nixon was taken by surprise—as he clearly was by the new material—you could almost see the wheels turning in his head and almost hear him asking himself what else his interrogator had up his sleeve. At the climactic moment, Frost, a natural performer, knew to change his role from inquisitor to confessor, to back off and allow Nixon's contrition to pour out.

In Aristotelian tragedy, the protagonist's suffering must have a larger meaning, and the result of it must be enlightenment. Nixon's performance fell short of that classical standard—he had been forced into his admission, and after he delivered it, he quickly reverted to blaming others for his transgressions. (His reversion to character was cut from the final broadcast.) With no lasting epiphany, Nixon would remain a sad, less-than-tragic, ambiguous figure.

For me, the transition from history to theater began with a letter from Peter Morgan, the acclaimed British screenwriter (The Queen), announcing his intention to write a play about the Frost-Nixon interviews. Since I loved the theater (and have written plays myself), I was happy to help in what seemed then a precious little enterprise.

At lunches in London and Washington, I spilled out my memories. And then I remembered that I had written a narrative of my involvement with Frost and Nixon, highlighting various tensions in the Frost camp and criticizing the interviewer for failing, until the end, to apply himself to his historic duty. Out of deference to Frost, I hadn't published it. My manuscript had lain forgotten in my files for 30 years. With scarcely a glance at it, I fished it out and sent it to Morgan.

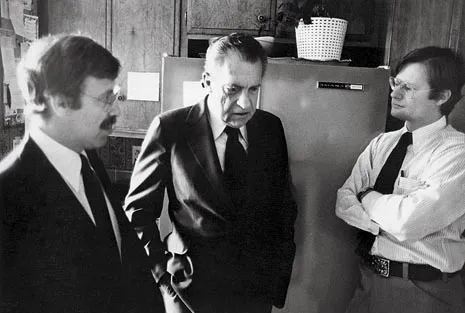

In the succeeding months I answered his occasional inquiry without giving the matter much thought. I sent Morgan transcripts of the conversations between Nixon and Colson that I had uncovered for Frost. About a year after first hearing from Morgan, I learned that the play was finished and would première at the 250-seat Donmar Warehouse Theatre in London with Frank Langella in the role of Nixon. Morgan asked if I would be willing to come over for a couple of days to talk to Langella and the other actors. I said I'd love to.

On the flight to London I reread my 1977 manuscript and I read the play, which had been fashioned as a bout between fading heavyweights, each of whose careers were on the wane, each trying to use the other for resurrection. The concept was theatrically brilliant, I thought, as well as entirely accurate. A major strand was the rising frustration of a character called Jim Reston at the slackness of a globe-trotting gadfly called David Frost. Into this Reston character was poured all the anger of the American people over Watergate; it was he who would prod the Frost character to be unrelenting in seeking the conviction of Richard Nixon. The play was a slick piece of work, full of laughs and clever touches.

For the play's first reading we sat round a simple table at the Old Vic, ten actors (including three Americans), Morgan, me and the director, Michael Grandage. "Now we're going to go around the table, and everyone is going to tell me, 'What was Watergate?'" Grandage began. A look of terror crossed the actors' faces, and it fell to me to explain what Watergate was and why it mattered.

The play, in two acts, was full of marvelous moments. Nixon had been humanized just enough, a delicate balance. To my amusement, Jim Reston was played by a handsome 6-foot-2 triathlete and Shakespearean actor named Elliot Cowan. The play's climax—the breaking of Nixon—had been reduced to about seven minutes and used only a few sentences from my Colson material. When the reading was over, Morgan turned to Grandage. "We can't do this in two acts," he said. The emotional capital built up in Act I would be squandered when theatergoers repaired to the lobby for refreshments and cellphone calls at intermission. Grandage agreed.

I knew not to argue with the playwright in front of the actors. But when Morgan and I retreated to a restaurant for lunch, I insisted that the breaking of Nixon happened too quickly. There was no grinding down; his admission was not "earned." I pleaded for the inquisition to be protracted, lengthened, with more of the devastating Colson material put back in.

Morgan resisted. This was theater, not history. He was the dramatist; he knew what he was doing. He was focused on cutting, not adding, lines.

Back at the theater, after a second reading, Langella took up my argument on his own. Nixon's quick collapse did not feel "emotionally right" to him, he said. He needed more lines. He needed to suffer more. Grandage listened for a while, but the actor's job was not to question the text, but to make the playwright's words work. The play would stay as written.

It opened in London on August 10, 2006, to terrific reviews. The critics raved about Langella's performance as Nixon, as well as Michael Sheen's as David Frost. (I tried not to take it personally when the International Herald Tribune critic, Matt Wolf, wrote, "Frost/Nixon provide[s] a snarky guide to [the] proceedings in the form of Elliot Cowan's bespectacled James Reston, Jr.") No one seemed to care about what was historically accurate and what had been made up. No one seemed to find Nixon's breaking down and subsequent contrition unsatisfying. Not even me. Langella had made it work, brilliantly...not through more words, but with shifting eyes, awkward pauses and strange, uncomfortable body language, suggesting a squirming, guilty man. Less had become more as a great actor was forced back on the essential tools of his art.

Langella had not impersonated Nixon, but had become a totally original character, inspired by Nixon perhaps, but different from him. Accuracy—at least within the walls of theater—did not seem to matter. Langella's performance evoked, in Aristotelian terms, both pity and fear. No uncertainty lingered about the hero's (or the audience's) epiphany.

In April 2007 the play moved to Broadway. Again the critics raved. But deep in his admiring review, the New York Times' Ben Brantley noted, "Mr. Morgan has blithely rejiggered and rearranged facts and chronology" and referred readers to my 1977 manuscript, which had just been published, at last, as The Conviction of Richard Nixon. A few days later, I heard from Morgan. Brantley's emphasis on the play's factual alterations was not helpful, he said.

Morgan and I had long disagreed on this issue of artistic license. I regarded it as a legitimate point between two people coming from different value systems. Beyond their historical worth, the 1977 Nixon interviews had been searing psychodrama, made all the more so by the uncertainty over their outcome—and the ambiguity that lingered. I did not think they needed much improving. If they were to be compressed, I thought they should reflect an accurate essence.

Morgan's attention was on capturing and keeping his audience. Every line needed to connect to the next, with no lulls or droops in deference to dilatory historical detail. Rearranging facts or lines or chronology was, in his view, well within the playwright's mandate. In his research for the play, different participants had given different, Rashômon-like versions of the same event.

"Having met most of the participants and interviewed them at length," Morgan wrote in the London program for the play, "I'm satisfied no one will ever agree on a single, 'true' version of what happened in the Frost/Nixon interviews—thirty years on we are left with many truths or many fictions depending on your point of view. As an author, perhaps inevitably that appeals to me, to think of history as a creation, or several creations, and in the spirit of it all I have, on occasion, been unable to resist using my imagination."

In a New York Times article published this past November, Morgan was unabashed about distorting facts. "Whose facts?" he told the Times reporter. Hearing different versions of the same events, he said, had taught him "what a complete farce history is."

I emphatically disagreed. No legitimate historian can accept history as a creation in which fact and fiction are equals. Years later participants in historical events may not agree on "a single, 'true' version of what happened," but it's the historian's responsibility to sort out who is telling the truth and who is covering up or merely forgetful. As far as I was concerned, there was one true account of the Frost/Nixon interviews—my own. The dramatist's role is different, I concede, but in historical plays, the author is on the firmest ground when he does not change known facts but goes beyond them to speculate on the emotional makeup of the historical players.

But this was not my play. I was merely a resource; my role was narrow and peripheral. Frost/Nixon—both the play and the movie—transcends history. Perhaps it is not even history at all: in Hollywood, the prevailing view is that a "history lesson" is the kiss of commercial death. In reaching for an international audience, one that includes millions unversed in recent American history, Morgan and Ron Howard, the film's director, make the history virtually irrelevant.

In the end it is not about Nixon or Watergate at all. It's about human behavior, and it rises upon such transcendent themes as guilt and innocence, resistance and enlightenment, confession and redemption. These are themes that straight history can rarely crystallize. In the presence of the playwright's achievement, the historian—or a participant—can only stand in the wings and applaud.

James Reston Jr. is the author of The Conviction of Richard Nixon and 12 other books.