George Jetson Gets A Check-Up

Medical diagnostics in the paleofuture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130102035127doctor-jetson-470x251.jpg)

This is the 14th in a 24-part series looking at every episode of “The Jetsons” TV show from the original 1962-63 season.

The 14th episode of “The Jetsons” originally aired in the U.S. on December 30, 1962, and was titled “Test Pilot.” This episode (like so many others) centers around the competition between Spacely Sprockets and Cogswell Cogs. Both companies have developed an invincibility suit which can supposedly withstand anything from gigantic sawblades to missiles being fired directly at it. The only trouble is that neither Mr. Spacely nor Mr. Cogswell can find any person brave enough (or dumb enough) to act as a human guinea pig and test the suit’s ability to keep its wearer safe.

George goes to the doctor for an insurance physical and gets some bad news. George swallows a Peek-A-Boo Prober Capsule which travels around the inside of his body showing the doctor (in a rather humorous way, of course) how George’s various organs are holding up. “You just swallow it and it transmits pictures to a TV screen,” the doctor explains. Through a series of mix-ups the doctor diagnoses George as having very little time to live. George then takes “live each day as if it were your last” quite literally and begins making hasty decisions — giving his family money to spend frivolously and telling off his boss, Mr. Spacely.

Mr. Spacely realizes that George’s newfound bravery may be just what he needs to test out the invincibility suit. Mr. Cogswell tries to poach the newly heroic Jetson for his company since he’s had no more luck than Mr. Spacely in finding a test pilot. Mr. Spacely wins out and George goes on testing the suit without a care in the world, acting rather calm for a man who believes that he’ll soon be six feet under. (Or six feet over? I don’t think “The Jetsons” ever addresses if people of the 21st century are buried or cremated or shot into space or something.)

After many death-defying tests, George discovers that the diagnosis was wrong and that he’s not going to die. George then reverts back to the lovable coward he always was and does his best to get out of the last test which just so happens to involve two missiles being shot at him. In the end, it wasn’t the missiles or the sawblades that destroyed the suit, but the washing machine — and George remarks that they should have included a “dry-clean only” tag.

The 1950s was an exciting decade for medicine with many important innovations — from Salk’s polio vaccine to the first organ transplant. These incredible advancements led many to believe that such marvelous medical discoveries would continue at an even more accelerated rate into the 21st century, including in how to diagnosis different diseases.

As Dr. Kunio Doi explains in his 2006 paper “Diagnostic Imaging Over the Last 50 Years” the science of seeing inside the human body has developed tremendously since the 1950s. The biggest hurdle in diagnostic imaging at mid-century was the manual processing of film which could be time consuming:

most diagnostic images were obtained by use of screen-film systems and a high-voltage x-ray generator for conventional projection x-ray imaging . Most radiographs were obtained by manual processing of films in darkrooms, but some of the major hospitals began to use automated film processors. The first automated film processor was a large mechanical system with film hangers, which was designed to replace the manual operation of film development; it was very bulky, requiring a large space, and took about 40 min to process a film.

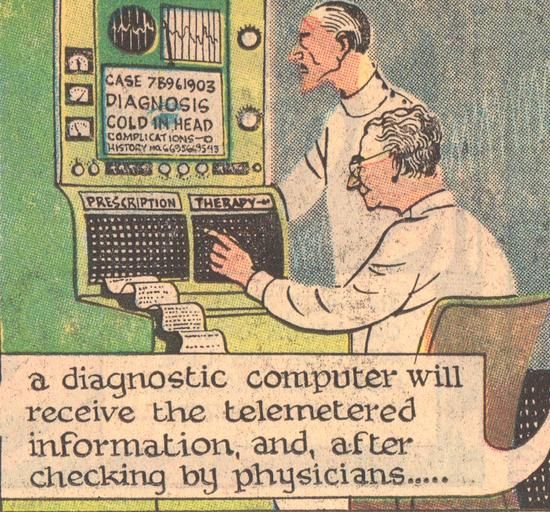

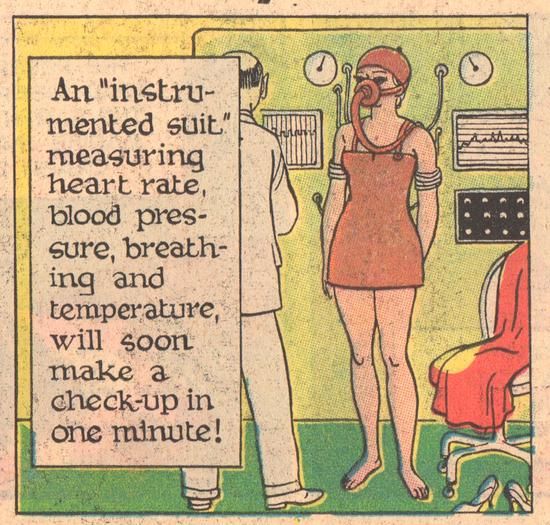

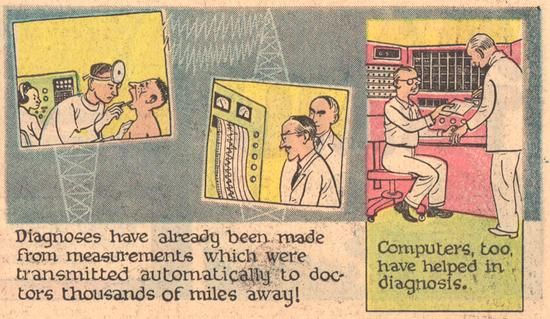

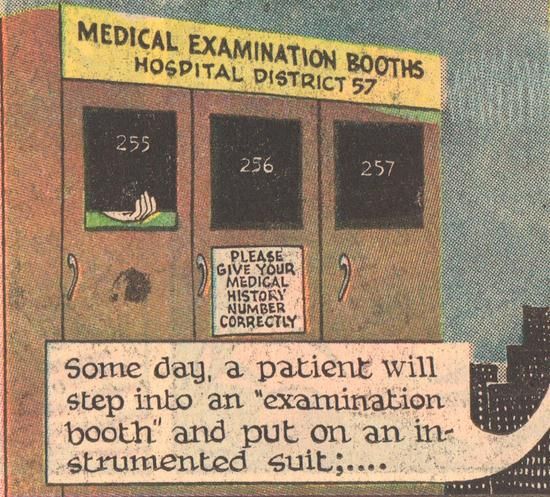

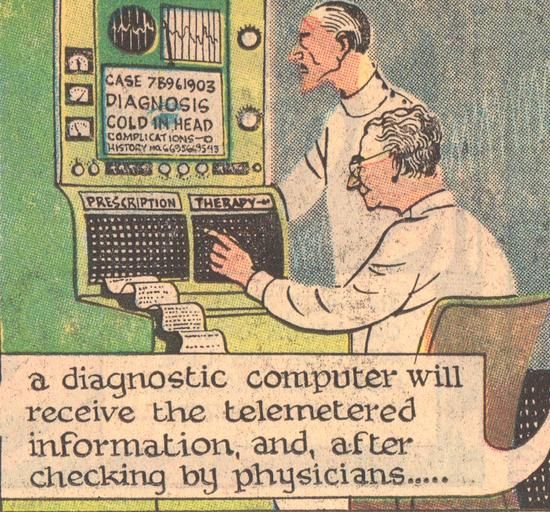

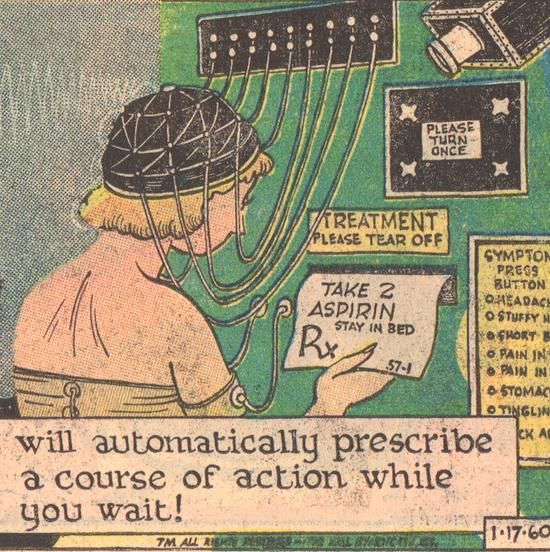

The January 17, 1960 edition of the Sunday comic strip Our New Age by Athelstan Spilhaus offered an optimistic look at the medical diagnostic instruments of the future:

The strip explains that one day patients might step into an “examination booth” while outfitted with a suit that measures all kinds of things at once — your heart rate, blood pressure, breathing and so on. This suit will, of course, be connected to a computer which will spit out data to be analyzed by a doctor. The prescription will then be “automatically” printed out for the patient.

Just as we see with George Jetson, “automatic” diagnosis in this comic strip from 1960 doesn’t mean that humans will be taken completely out of the picture. Doctors of the future, we were told, will still play a vital role in analyzing information and double-checking the computer’s diagnosis. As Dr. Doi notes in his paper, we’ve made tremendous strides in the last 50 years of diagnosis. But I suppose we’re still waiting on that invincibility suit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)