Getting up Close and Personal with American Soldiers

A new photography exhibit takes a multi-decade look

In 2011, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Mike Mullen, said in a speech before the National Defense University, “America doesn’t know its military and the United States military doesn’t know America.”

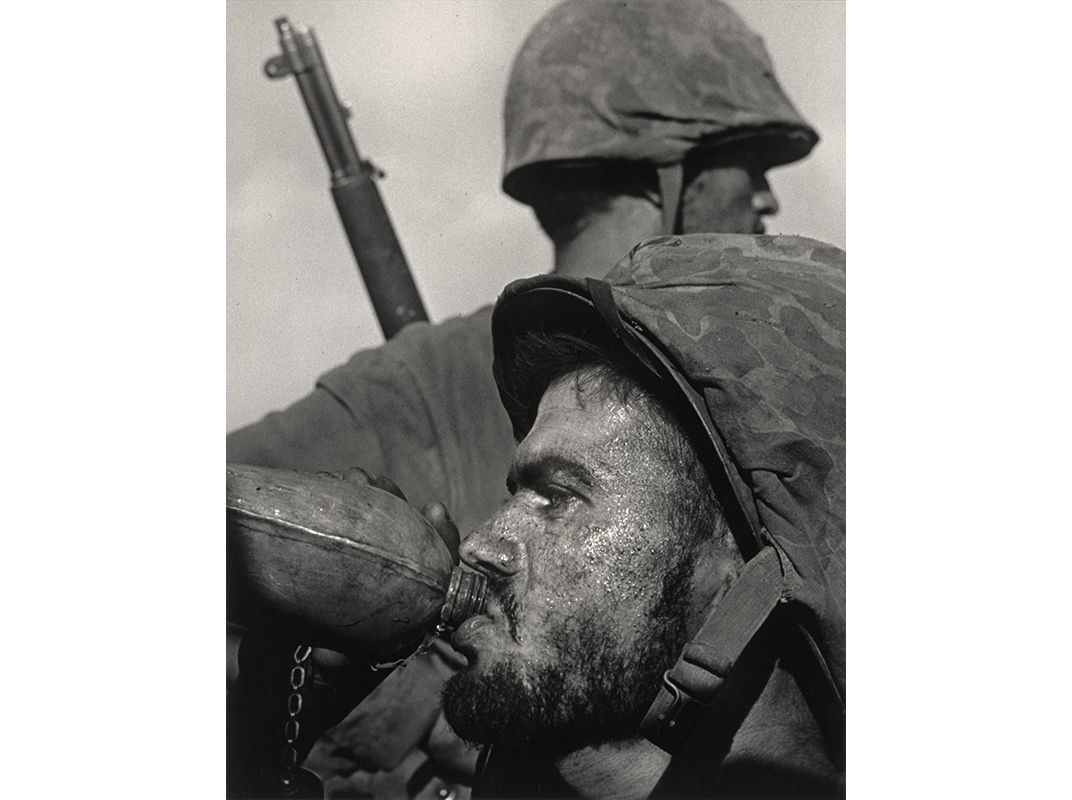

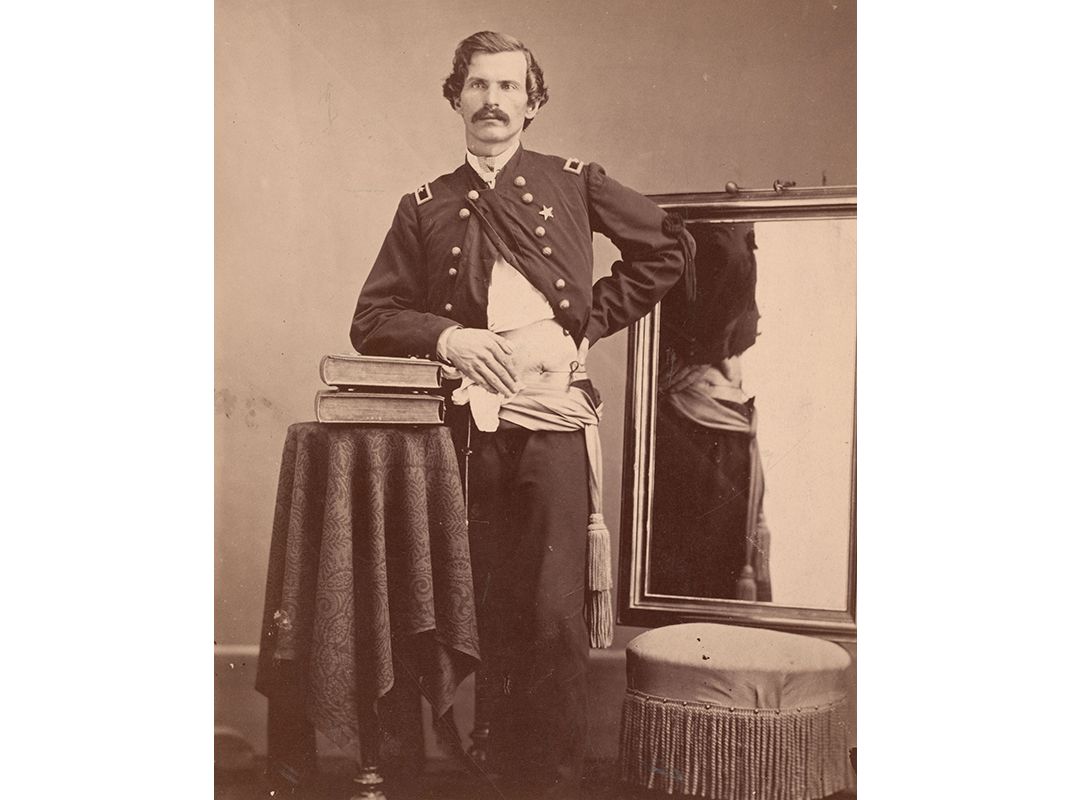

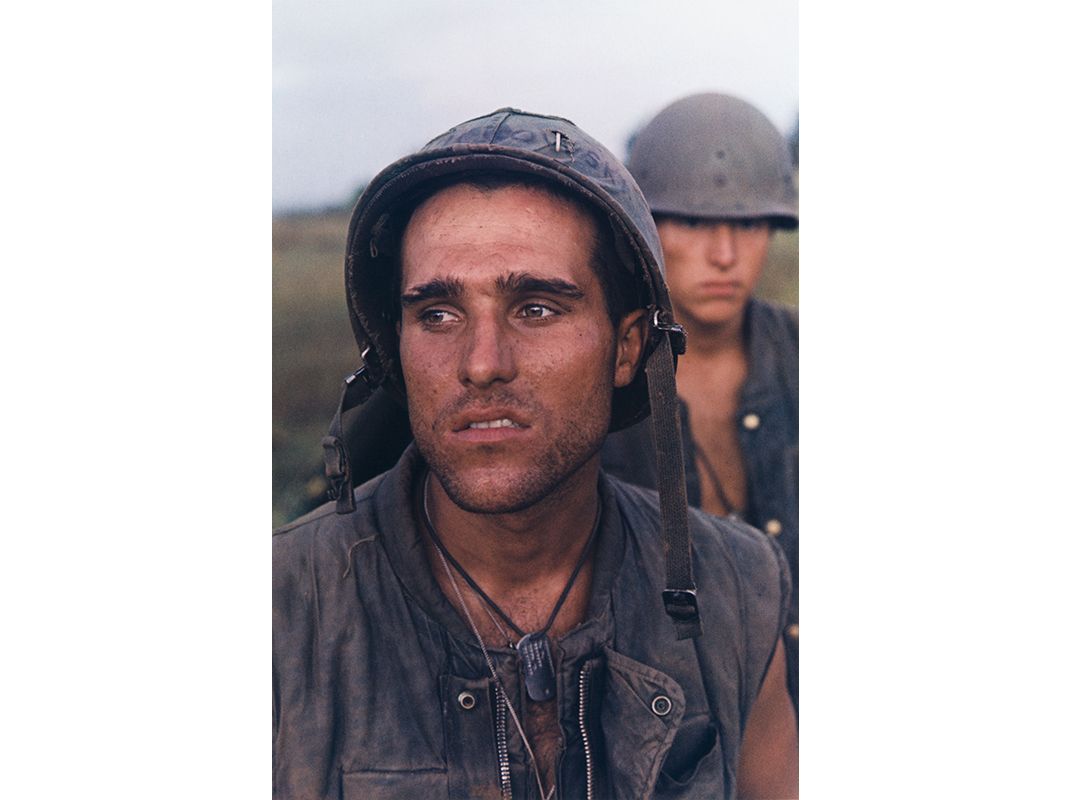

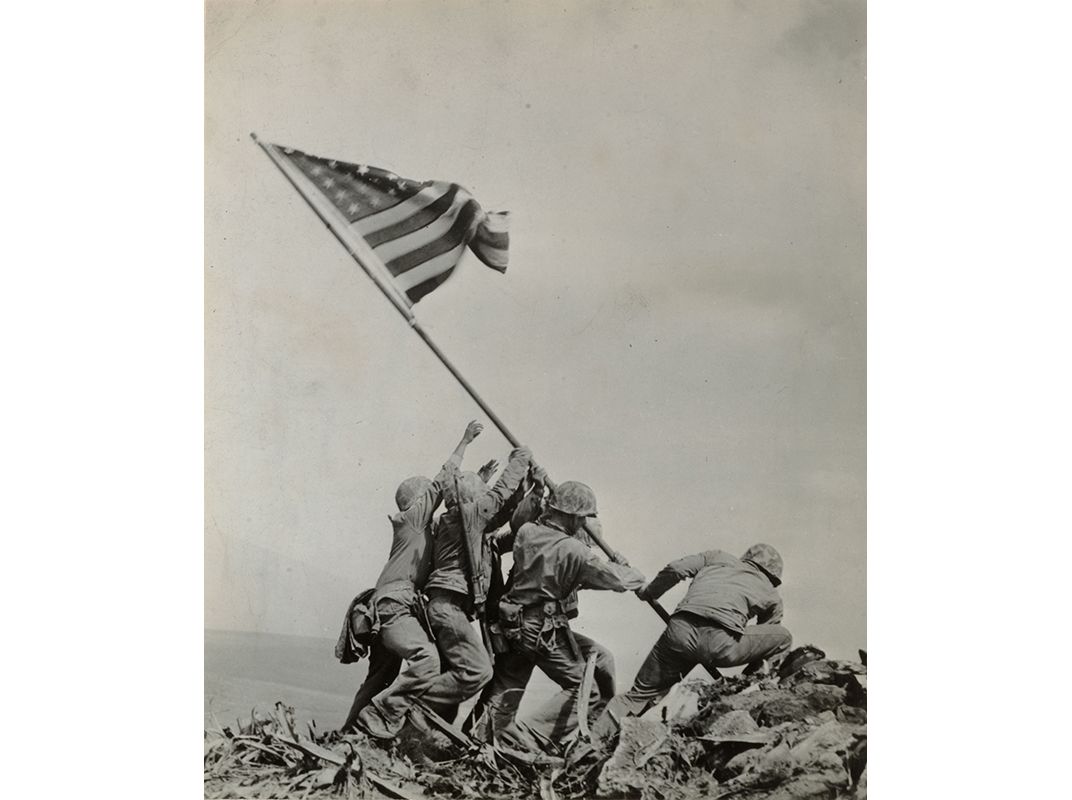

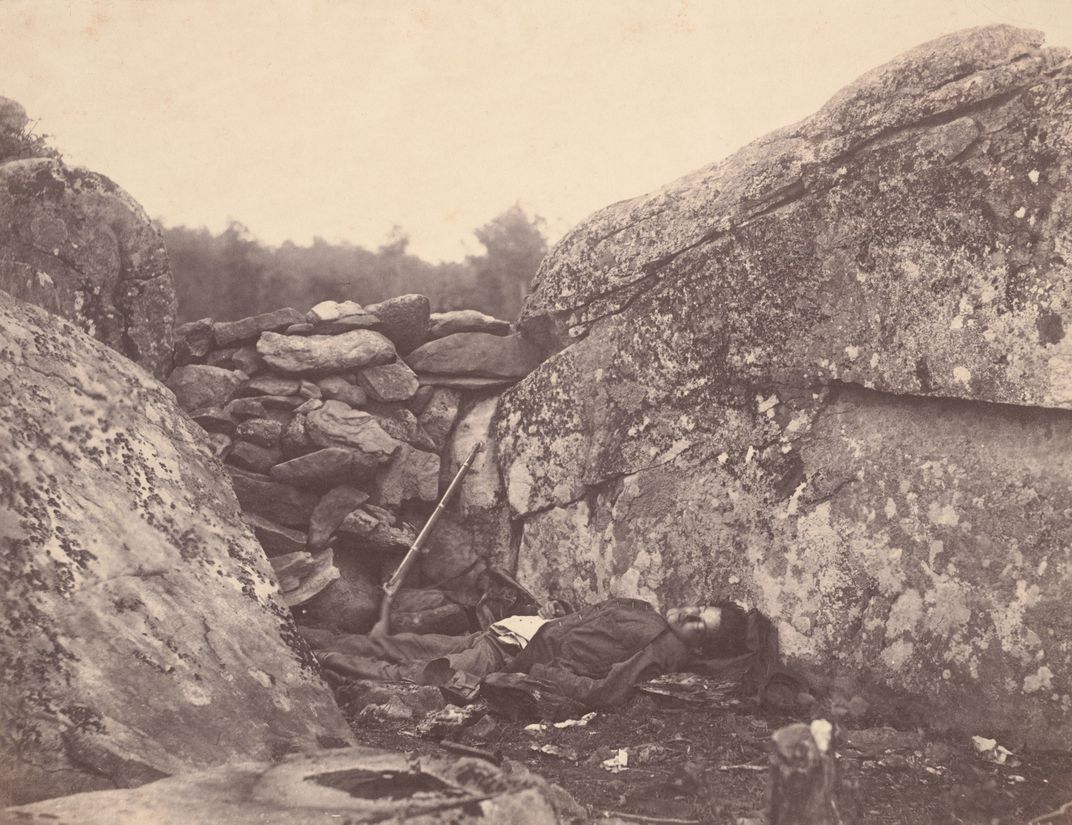

Curator April Watson celebrates photography as a way to close this gap between the military and American civilians. This week, the show “American Soldier” opened at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The exhibition explores how advancements in camera technology have changed the feeling of war photographs. In the early days of photography, bulky cameras took time to set up, and subjects needed to remain relatively still. As technology advanced, photographs displayed the action of war more and more, and were able to get up close and personal with soldiers.

The intimate relationship between soldiers and photography continually changes. April Watson hopes that connecting with that relationship will help visitors to reconnect with the soldier’s experience.

I spoke with Watson, about how she made her selections. The exhibition is on view through June 21.

What was your initial inspiration for the exhibit?

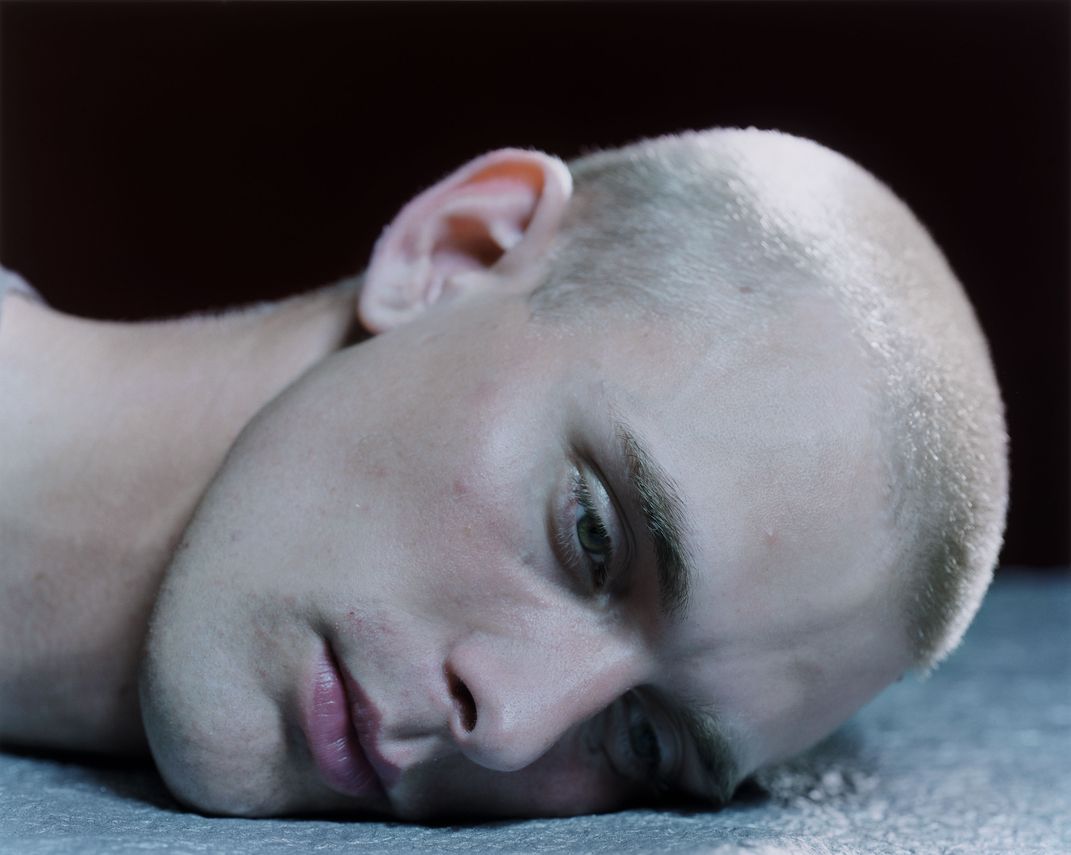

The idea came when the museum acquired a couple of works by Suzanne Opton and Richard Mosse. I was noticing that several contemporary artists and photojournalists were focusing on the individual stories of soldiers and military personnel that were coming back form Iraq and Afghanistan, and they were making different kind of pictures than I had been used to seeing. And [the Nelson-Atkins Museum has] such a strong collection of iconic pictures from the Civil War and World War II! I thought that is might be interesting to bring all of them together and think about the different ways that photographs have shaped our perspectives of soldiers over time.

What do you think the wide timespan brings to the exhibition?

I think people would be interested to see how the technologies change over time, and how that has impacted the parts of the soldier’s experience that were shown. In the 19th century, during the time of large format view cameras and Collodion on glass negatives, you don’t get up close images of soldiers. In World War II, the handheld Leica camera felt liberating for a lot of photographers, as they were finally able to get in close to their subjects. I think you wouldn’t get a sense for those parts of history if the exhibition just focused on contemporary photography.

How do you think this exhibition differs from other war photography exhibitions that don’t necessarily focus on that history?

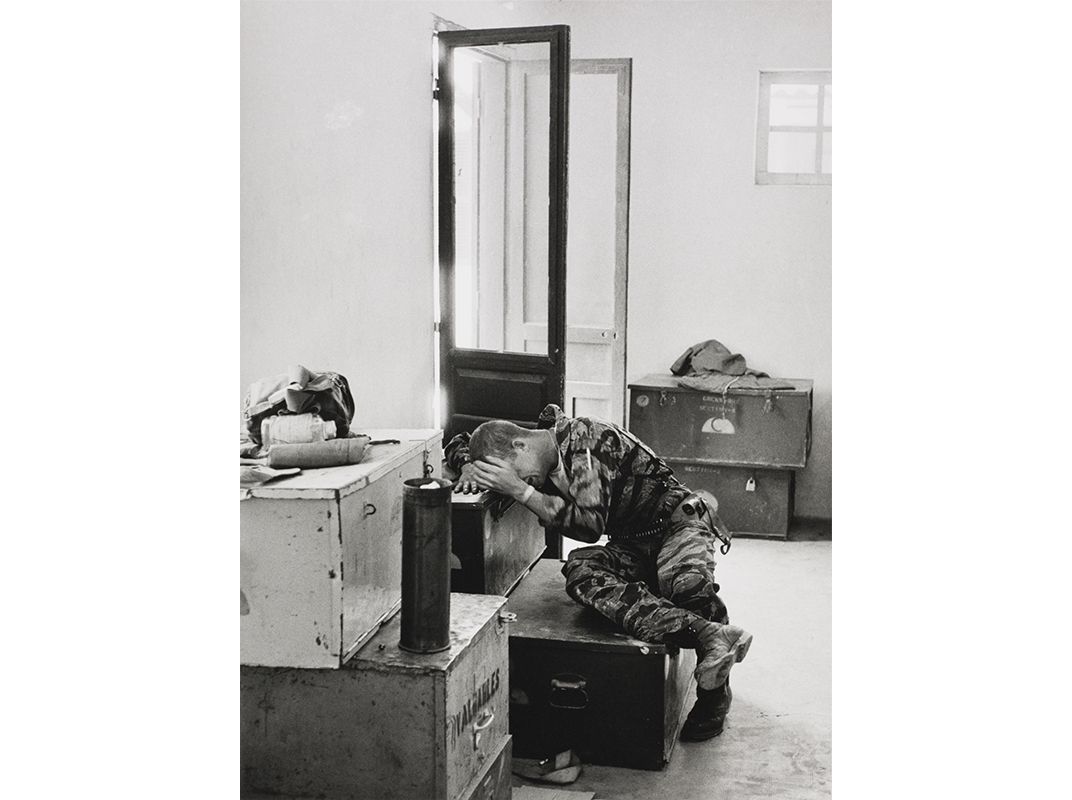

The exhibition is not meant to be epic in scale. There are no pictures of military strategy or aerial photographs, no landscapes. The show is mostly focused on portraits, centering on individual soldiers.

Is there a certain mood or message that you hope viewers will gain from the exhibition?

It’s a somber show for sure, but I tried to present the work in a neutral manner and to focus on the photographer’s intention, on the context, and who it was made for. I wanted to allow the viewers to read the images as they will. The general public will come to the show, and maybe they will have a personal connection to the military and maybe they won’t. I actually think people are very distanced from the soldier’s experience, especially in the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Do you think there’s a difference between art and photojournalism, and if so where do you think they overlap?

I think of art photography as the making of photographs that allow for a more complex reading of an image. And you’re not necessarily able to understand what the image is about in a split second. However, there’s no hard and fast rule there. Artists like Larry Burrows who worked in Vietnam, Tim Hetherington, or Ashley Gilbertson all may be working as photo-journalists or for news agencies, but they also make pictures that transcend that conveying of information. They make images that linger with you. It can be a grey area, but that’s how I’m thinking about it.