Harriet Tubman’s Hymnal Evokes a Life Devoted to Liberation

A hymnal owned by the brave leader of the Underground Railroad brings new insights into the life of the American heroine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-Harriet-Tubman-631.jpg)

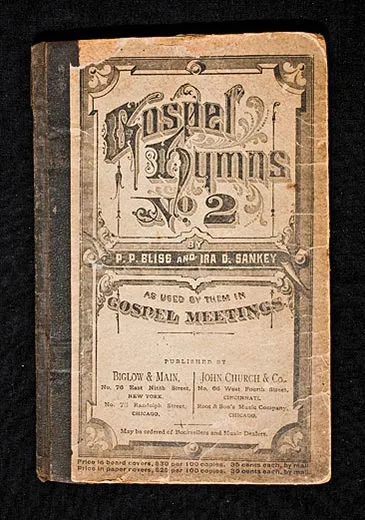

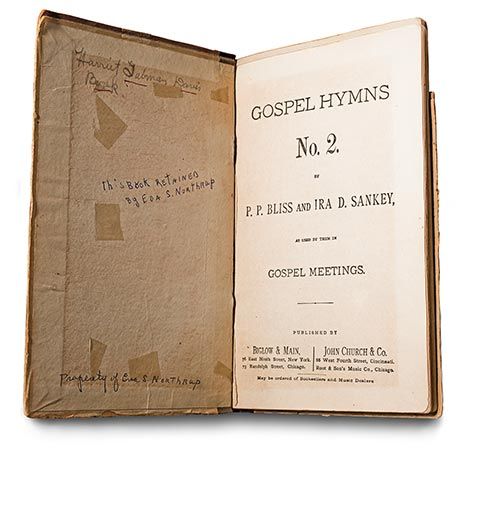

An 8- by 5-inch 19th-century hymnal, bound in faded paperboard and cloth, bears its owner’s name handwritten on the inside cover. The well-worn book of hymns belonged to one of American history’s most legendary heroines: Harriet Tubman.

Historian Charles Blockson recently donated the hymnal—along with other Tubman memorabilia—to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. It represents, says NMAAHC director Lonnie Bunch, an opportunity “to renew our awareness of Harriet Tubman as a human—to make her less of a myth and more of a girl and a woman with astonishing determination.”

Historians continue to investigate the inscription on the inside cover—“Harriet Tubman Davis Book.” (Tubman married Nelson Davis, a Civil War veteran, in 1869.) Denied education as a slave, Tubman, according to historical evidence, never learned to read or write. “We have more study to do,” says Bunch.

Born in 1822 in Maryland, Tubman suffered a serious head injury as a girl, when an overseer hurled a scale counterweight at another slave, hitting Tubman. The injury caused lifelong seizures and hallucinations that the young woman would interpret as religious visions.

In 1849, she fled Maryland to Philadelphia. Soon after, Tubman began her exploits—acts of bravery that would make her a legend. She returned secretly to Maryland to begin escorting other slaves to freedom. She often traveled at night to avoid capture by reward-seeking trackers. During the course of 13 such missions, she led nearly 70 slaves out of bondage. Even after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required free states to return runaway slaves, Tubman continued to guide her charges along the Underground Railroad north to Canada, earning the nom de guerre “Moses.” She would later recall with pride that she “never lost a passenger.”

“She believed in freedom when she shouldn’t have had a chance to believe in freedom,” says Bunch. Just as important, he adds, was that her increasingly famous acts of daring “belied the Southern contention that slaves actually liked their lives.”

During the Civil War, Tubman served with the Union Army as a rifle-toting scout and spy. In June 1863, she helped lead a gunboat raid on plantations along the Combahee River near Beaufort, South Carolina, an action that freed more than 700 slaves. As Union gunboats took on those who fled, Tubman calmed fears with a familiar abolitionist anthem:

Of all the whole creation in the east

or in the west

The glorious Yankee nation is the

greatest and the best

Come along! Come along!

don’t be alarmed.

In her long, eventful life, Tubman worked with abolitionist Frederick Douglass; anti-slavery firebrand John Brown (who called her “General Tubman”); and women’s rights pioneer Susan B. Anthony. In 1897, Queen Victoria recognized her achievements with the gift of a lace-and-silk shawl. (The garment is among 39 items in the Blockson donation.) Tubman died in 1913 at age 91, in Auburn, New York, where she had founded a nursing home for former slaves after the war.

Blockson, who lives outside Philadelphia, has since boyhood amassed material relating, he says, to “anyone of African descent.” Today, he is curator emeritus of his collection—numbering some 500,000 pieces—at Temple University.

He acquired the hymnal, the Victoria shawl, several rare photographs and other items as a bequest from Meriline Wilkins, Tubman’s great-great-niece who died at age 92 in 2008. The hymnal had belonged to Tubman’s great-niece, Eva S. Northrup. “[Meriline] said to me once, ‘I’m going to give you something one of these days,’” Blockson recalls. “But when the hymnal turned out to be one of the things she left to me, it was awesome to receive it. And it had to go to Washington, where it may attract other Tubman items.”

The gospel song “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which is in the hymnal, was among Tubman’s favorites. Says Blockson: “They sang it at her funeral.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)