The Holocaust’s Great Escape

A remarkable discovery in Lithuania brings a legendary tale of survival back to life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/f6/48f6f3fc-8149-4d59-8fc9-f13c15dac5a7/mar2017_h01_lithuania.jpg)

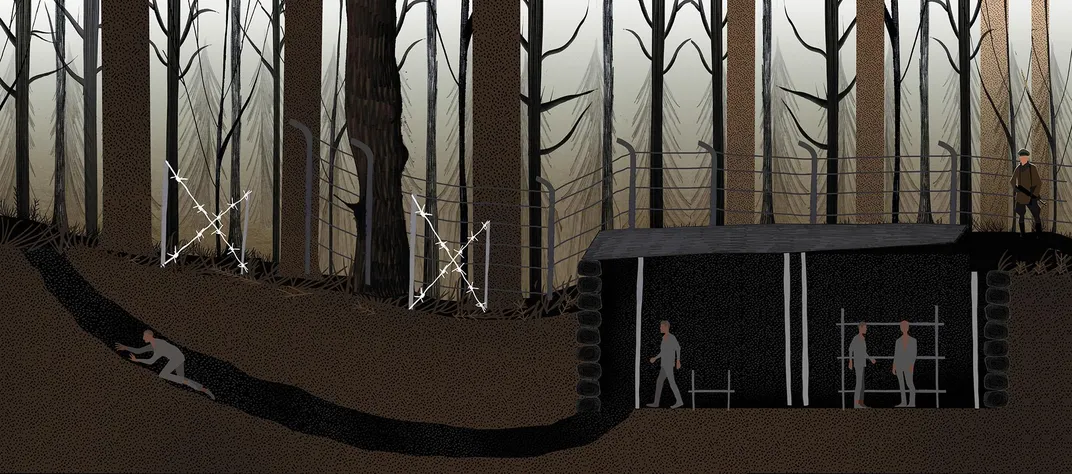

Shortly after dawn one January day in 1944, a German military truck departed the center of Vilnius, in what is today Lithuania, and rattled southwest toward the fog-laced towns that ringed the city. Near the village of Ponar, the vehicle came to a halt, and a pale 18-year-old named Motke Zeidel, chained at the ankles, was led from the cargo hold.

Zeidel had spent the previous two years in German-occupied Vilnius, in the city’s walled-off Jewish ghetto. He’d watched as the Nazis sent first hundreds and then thousands of Jews by train or truck or on foot to a camp in the forest. A small number of people managed to flee the camp, and they returned with tales of what they’d seen: rows of men and women machine-gunned down at close range. Mothers pleading for the lives of their children. Deep earthen pits piled high with corpses. And a name: Ponar.

Now Zeidel himself had arrived in the forest. Nazi guards led him through a pair of gates and past a sign: “Entrance Strictly Forbidden. Danger to life. Mines.” Ahead, through the gaps in the pines, he saw massive depressions in the ground covered with fresh earth—the burial pits. “This is it,” he said to himself. “This is the end.”

The Nazi killing site at Ponar is today known to scholars as one of the first examples of the “Holocaust by bullets”—the mass shootings that claimed the lives of upwards of two million Jews across Eastern Europe. Unlike the infamous gas chambers at places like Auschwitz, these murders were carried out at close range, with rifles and machine guns. Significantly, the killings at Ponar marked the transition to the Final Solution, the Nazi policy under which Jews would no longer be imprisoned in labor camps or expelled from Europe but exterminated.

Zeidel braced for the crack of a rifle.

It never came. Opening his eyes, he found himself standing face to face with a Nazi guard, who told him that beginning immediately, he must work with other Jewish prisoners to cut down the pine trees around the camp and transport the lumber to the pits. “What for?” Zeidel later recalled wondering. “We didn’t know what for.”

A week later, he and other members of the crew received a visit from the camp’s Sturmbannführer, or commander, a 30-year-old dandy who wore boots polished shiny as mirrors, white gloves that reached up to his elbows, and smelled strongly of perfume. Zeidel remembered what the commandant told them: “Just about 90,000 people were killed here, lying in mass graves.” But, the Sturmbannführer explained, “there must not be any trace” of what had happened at Ponar, lest Nazi command be linked to the mass murder of civilians. All the bodies would have to be exhumed and burned. The wood collected by Zeidel and his fellow prisoners would form the pyres.

By late January, roughly 80 prisoners, known to historians as the Burning Brigade, were living in the camp, in a subterranean wood-walled bunker they’d built themselves. Four were women, who washed laundry in large metal vats and prepared meals, typically a chunk of ice and dirt and potato melted down to stew. The men were divided into groups. The weaker men maintained the pyres that smoldered through the night, filling the air with the heavy smell of burning flesh. The strongest hauled bodies from the earth with bent and hooked iron poles. One prisoner, a Russian named Yuri Farber, later recalled that they could identify the year of death based on the corpse’s level of undress:

People who were murdered in 1941 were dressed in their outer clothing. In 1942 and 1943, however, came the so-called “winter aid campaign” to “voluntarily” give up warm clothing for the German Army. Beginning in 1942, people were herded in and forced to undress to their underwear.

Double-sided ramps were built inside the pits. One crew hauled stretchers filled with corpses up the ramp, and another crew pushed the bodies onto the pyre. In a week, the Burning Brigade might dispose of 3,500 bodies or more. Later, the guards forced prisoners to sift through the ashes with strainers, looking for bone fragments, which would then be pounded down into powder.

All told, historians have documented at least 80,000 people shot at Ponar between 1941 and 1944, and many believe the true number is greater still. Ninety percent of those killed were Jews. That the Nazis charged a brigade of prisoners to disinter and dispose of the bodies, in the most sickening of circumstances, only amplifies the horror.

“From the moment when they made us bring up the corpses, and we understood that we wouldn’t get out of there alive, we reflected on what we could do,” Zeidel remembered.

And so the prisoners turned to one thought: escape.

**********

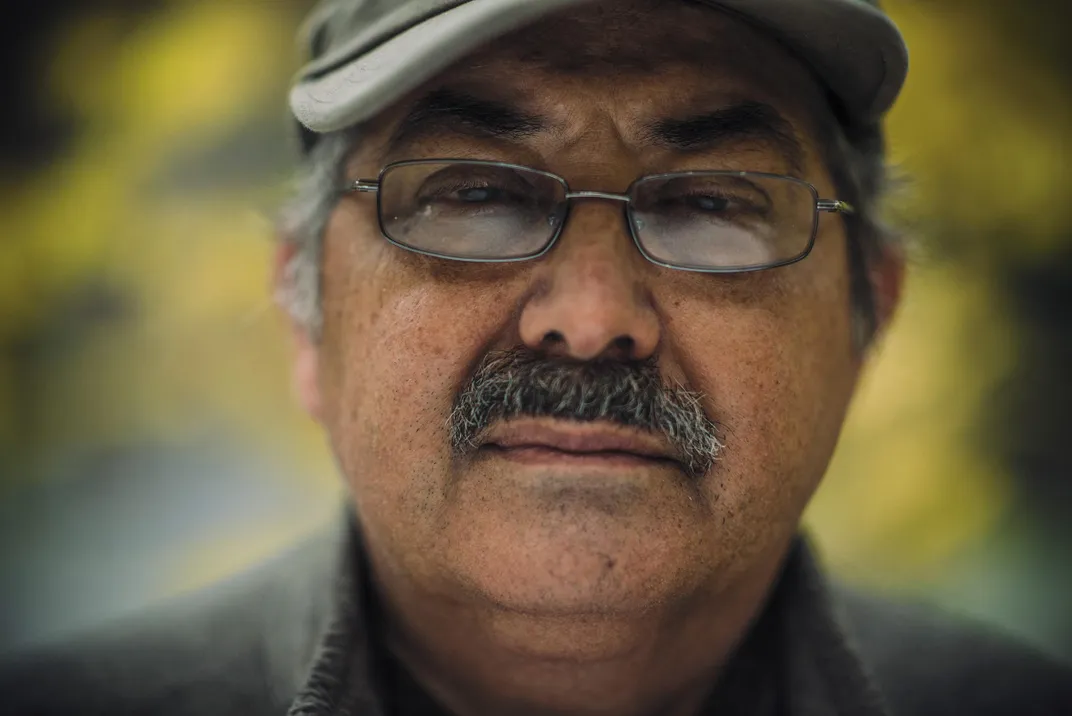

Richard Freund, an American archaeologist at the University of Hartford, in Connecticut, specializes in Jewish history, modern and ancient. He has been traversing the globe for almost three decades, working at sites as varied as Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, and at Sobibor, a Nazi extermination camp in eastern Poland. Unusually for a man in his profession, he rarely puts trowel to earth. Instead, Freund, who is rumpled and stout, with eyes that seem locked in a perpetual squint, practices what he calls “noninvasive archaeology,” which uses ground-penetrating radar and other types of computerized electronic technology to discover and describe structures hidden underground.

One day this past fall I walked the grounds of the Ponar forest with Freund and a couple of his colleagues, who had recently completed a surveying project of the area. Snow had been forecast, but by late morning the only precipitation was icy rain, driven sideways by the wind. The forest was mostly empty, save for a group of ten Israelis who had arrived that morning; they all had family from Vilnius, one of the men explained, and were honoring them by visiting local Holocaust sites.

I followed Freund up a short slope and past a trench where prisoners had been lined up and shot. It was now a barely perceptible dip in the loam. Freund stepped gingerly around it. In the distance, a train whistle howled, followed by the huff of a train, shuddering over tracks that had carried prisoners to their deaths decades earlier. Freund waited for it to pass. He recalled that he’d spent nearly a month researching the site—but “a few days,” he said, “is plenty of time to think about how many people died here, the amount of blood spilled.”

Although he was raised some 5,000 miles from Lithuania, on Long Island, New York, Freund has deep roots in the area. His great-grandparents fled Vilnius in the early 20th century, during an especially violent series of pogroms undertaken by the Czarist government, when the city still belonged to the Russian Empire. “I’ve always felt a piece of me was there,” Freund told me.

Which made him all the more intrigued to hear, two years ago, about a new research project led by Jon Seligman, of the Israel Antiquities Authority, at the site of Vilnius’s Great Synagogue, a once towering Renaissance-Baroque structure dating to the 1630s. The synagogue, which had also housed a vast library, kosher meat stalls and a communal well, had at one time been the crown jewel of the city, itself a center of Jewish life in Eastern Europe—the “Jerusalem of the North.” By one estimate, at the turn of the 20th century Vilnius was home to some 200,000 people, half of them Jewish. But the synagogue was damaged after Hitler’s army captured the city in June 1941 and herded the Jewish population into a pair of walled ghettos, whom it then sent, in successive waves, to Ponar. After the war the Soviets razed the synagogue entirely; today an elementary school stands in its place.

Lithuanian archaeologists had discovered remnants of the old synagogue—evidence of several intact subterranean chambers. “The main synagogue floor, parts of the grand Tuscan pillars, the bimah”—or altar—“the decorated ceiling,” Freund explained. “All of that had been underground, and it survived.”

Freund and his colleagues, including Harry Jol, a professor of geology and anthropology from the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, and Philip Reeder, a geoscientist and mapping expert from Duquesne University, in Pittsburgh, were brought in to explore further. They spent five days scanning the ground beneath the school and the surrounding landscape with ground-penetrating radar, and emerged with a detailed digital map that displayed not just the synagogue’s main altar and seating area but also a separate building that held a bathhouse containing two mikvaot, or ceremonial baths, a well for water and several latrines. Afterward, Freund met with the staff at the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, named after the famed 18th-century Talmudic scholar from Vilnius, and a partner on the Great Synagogue project. Then, Freund said, “We asked them: ‘What else would you like us to do? We’ll do it for free.’”

The next day, a museum staffer named Mantas Siksnianas took Freund and his crew to the forests of Ponar, a 20-minute drive from the city center. Most of the nearby Nazi-era burial pits had been located, Siksnianas explained, but local archaeologists had found a large area, overgrown with foliage, that looked as if it might be an unidentified mass grave: Could Freund and his colleagues determine if it was?

As Siksnianas led Freund through the woods, he told an astonishing story about a group of prisoners who had reportedly tunneled to freedom and joined partisan fighters hiding out in the forest. But when Freund asked to see exactly how they made it out, he got only shrugs. No one could show him; no one knew. Because a tunnel had never been definitively located and documented, the story had come to take on the contours of a fable, and three-quarters of a century on, it seemed destined to remain a legend without any verifiable evidence to back it up—a crucial piece of the historical record, lost to time.

So the following year, in June 2016, Freund returned with two groups of researchers and their equipment and for the first time mapped the unknown areas of the site, including any unmarked mass graves. Then, using a collection of aerial photographs of Ponar shot by Nazi reconnaissance planes and captured during the war, which helped give the researchers a better sense of the camp’s layout, Freund and his colleagues turned their attention to finding clues about how the camp’s fabled survivors were able to find a way out. (A “Nova” television documentary about the discoveries found in Vilnius, "Holocaust Escape Tunnel" will premiere on PBS on April 19. Check your local listings for times.)

Relying on a surveying device known as a total station—the tripod-mounted optical instrument employed by construction and road crews—Reeder set about measuring minute elevation changes across the land, searching for subtle gradations and anomalies. He zeroed in on a hummock that looked like the earthen side of a bunker, long since overgrown with moss and foliage, and roughly 100 feet away, a telltale dip in the earth.

Although the composition of the ground, largely sand, was favorable for ground-penetrating radar, the dense forest surrounding the site interfered enough with the radar signals that they decided to try another tack. Paul Bauman and Alastair McClymont, geophysicists with Advisian WorleyParsons, a transnational engineering company, had more luck with electrical resistivity tomography, or ERT, which was originally developed to explore water tables and potential mining sites. ERT technology sends jolts of electrical current into the earth by way of metal electrodes hooked up to a powerful battery and measures the distinctive levels of resistivity of different types of earth; the result is a detailed map to a depth of more than a hundred feet.

“We were able to get a readout not in real time, but close to it,” McClymont told me. “We’d pull the data off the control box, transfer it to a laptop we had with us in the field, run the data through software that does the conversion, and then we could see it”—a sliver of red against a backdrop of blue.

They were looking at a tunnel.

**********

The digging got underway the first night in February 1944, in a storeroom at the back of the bunker. To disguise their efforts, the prisoners erected a fake wall over the tunnel’s entrance, with “two boards hanging on loose nails that would come out with a good tug, making it possible to pass through,” Farber recalled in The Complete Black Book of Russian Jewry, a compilation of eyewitness testimonies, letters and other documents of the Nazi campaign against Jews in Eastern Europe published in part in 1944 and translated into English in 2001.

The men worked in shifts throughout the night, with saws, files and spoons stolen from the burial pits. Under the cover of darkness, they smuggled wood planks into the lengthening tunnel to serve as struts; as they dug, they brought sandy earth back out and spread it across the bunker floor. Any noise was concealed by the singing of the other prisoners, who were frequently forced to perform for the Sturmbannführer—arias from The Gypsy Baron, by the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II, were a favorite.

After a day of disinterring and burning corpses, “we returned [to the bunker] on all fours,” Zeidel recalled years later, in a series of interviews with the filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, today held at an archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “We really fell like the dead. But,” Zeidel continued, “the spirit of initiative, the energy, the will that we had” helped sustain them. Once oxygen in the tunnel became too scarce to burn candles, a prisoner named Isaac Dogim, who had worked in Vilnius as an electrician, managed to wire the interior with lights, powered by a generator the Nazis had placed in the bunker. Behind the fake wall, the tunnel was expanding: 10 feet in length, 15. Gradually, the entire Burning Brigade was alerted to the escape plan. Dogim and Farber promised that no one would be left behind.

There were setbacks. In March, the diggers discovered they were tunneling in the direction of a burial pit and were forced to reroute the passageway, losing days in the process. Not long afterward, Dogim was on burial pit duty when he unearthed the bodies of his wife, mother and two sisters. Every member of the Burning Brigade lived with the knowledge that some of the corpses he was helping to burn belonged to family members. And yet to see one’s wife lying in the pit was something else entirely, and Dogim was consumed with sadness and fury. “[He] said he had a knife, that he was going to stab and kill the Sturmbannführer,” Farber later recalled. Farber told Dogim that he was thinking selfishly—even if he succeeded, the rest of the prisoners would be killed in retribution.

Dogim backed down; the diggers pressed on. On April 9, Farber announced that they’d reached the roots of a tree near the barbed-wire fence that encircled the camp’s perimeter. Three days later, he made a tentative stab with a makeshift probe he’d fashioned out of copper tubing. Gone was the stench of the pits. “We could feel the fresh April air, and it gave us strength,” he later recalled. “We saw with our own eyes that freedom was near.”

The men selected April 15, the darkest night of the month, for the escape. Dogim, the unofficial leader of the group, was first—once he emerged from the tunnel, he would cut a hole in the nearby fence and mark it with a white cloth, so the others would know which direction to run. Farber was second. Motke Zeidel was sixth. The prisoners knew that a group of partisan fighters were holed up nearby, in the Rudnitsky Woods, in a secret camp from which they launched attacks on the Nazi occupiers. “Remember, there is no going back under any circumstances,” Farber reminded his friends. “It is better to die fighting, so just keep moving forward.”

They set off at 11 p.m., in groups of ten. The first group emerged from the tunnel without incident. Zeidel recalled slithering on his stomach toward the edge of the camp. He scarcely dared to exhale; his heart slammed against his chest wall. Later, Farber would speculate that it was the snap of a twig that alerted their captors to the escape. Dogim attributed it to a blur of movement spotted by the guards.

The forest burst orange with gunfire. “I looked around: Our entire path was filled with people crawling,” Farber has written. “Some jumped up and started running in various directions.” Farber and Dogim cut through the fence and tore off into the woods, with Zeidel and three others in tow. The men ran all night, through rivers, through forests, past villages. After a week, the escapees were deep inside the Rudnitsky Woods. Farber introduced himself to the partisan leader. “Where do you come from?” the man asked.

“From the other world,” Farber said.

“Where’s that?”

“Ponar.”

**********

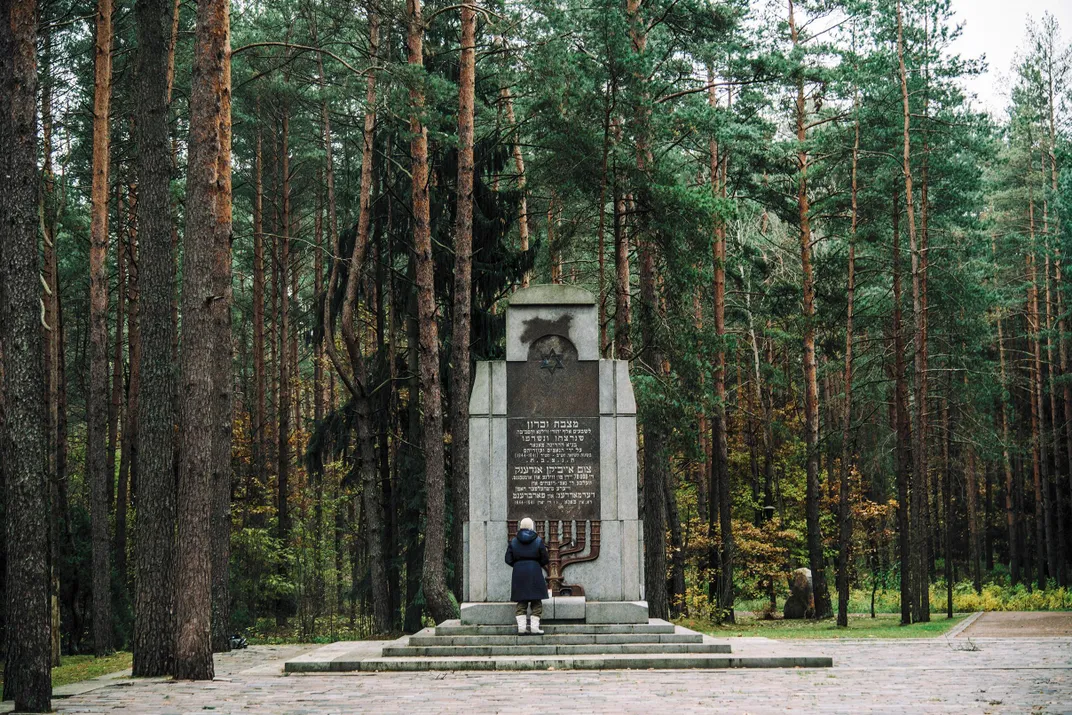

The killing grounds at Ponar are today part of a memorial site run by the Vilna Gaon Museum, in Vilnius. There is a granite obelisk inscribed with the date of the Soviet liberation of the region, and clusters of candles smoldering in the small shrines on the edge of the burial pits, in honor of the tens of thousands who perished here. A small museum near the entrance to the site collects photographs and testimonies from the camp. One enters the museum prepared to weep, and leaves insensate: The black-and-white images of tangled human limbs in a ditch, the crumpled corpses of children, the disinterred dead piled in wheelbarrows, waiting to be brought to the pyres—the effect of the material is deeply physical and hard to shake.

Not long after beginning the survey of the site, Freund and his team confirmed the existence of a previously unmarked burial pit. At 80 feet across and 15 feet deep, the scientists calculated that the grave contained the cremated remains of as many as 7,000 people. The researchers also released the preliminary results of their search for the tunnel, along with a series of ERT-generated cross sections that revealed the tunnel’s depth beneath the ground’s surface (15 feet at points) and its dimensions: three feet by three feet at the very widest, not much larger than a human torso. From the entrance inside the bunker to the spot in the forest, now long grown over, where the prisoners emerged measured more than 110 feet. At last, there was definitive proof of a story known until now only in obscure testimonies made by a handful of survivors—a kind of scientific witness that transformed “history into reality,” in the words of Miri Regev, Israel’s minister of culture, who highlighted the importance of documenting physical evidence of Nazi atrocities as a bulwark against “the lies of the Holocaust deniers.”

On June 29, the Times of Israel reported on the discovery: “New tech reveals forgotten Holocaust escape tunnel in Lithuania.” News media around the world picked up the story, including the BBC and the New York Times. To Freund, finding the tunnel finally made it possible to fully comprehend the perseverance the escapees had demonstrated. “What people were so captivated by, I think, was that this was a tale of hope,” he told me. “It proved how resilient humans can be.”

Freund and I walked the path of the tunnel, over the large hummock of earth, out toward the surrounding pines. Not such a long distance on foot, perhaps, but positively heroic when one considered that it had been dug, night after night, by chained men who had spent their daylight hours laboring at their unthinkable task, subsisting on nothing more than gruel.

“Could the tunnel ever be excavated?” I asked Freund. He told me that the Vilna Gaon Museum, although already planning renovations at the site, was still deciding how to proceed, but that he has counseled against full excavation: He’d invited an architect and tunnel expert named Ken Bensimon to analyze the site, and Bensimon had concluded that even if a rabbi signed off on a dig—a necessity, given the proximity to what amounts to mass graves—the integrity of the passageway would be unlikely to hold.

“I’ve offered three possibilities” to the museum, Freund said. The first was to try to partially excavate one section of the tunnel and protect it with climate-controlling plexiglass walls. Alternatively, a re-creation could be built, as had been done with the recently finished facsimile of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, in the Valley of the Kings, in Egypt. The last option, Freund allowed, was a “little futuristic”: Relying on the data from the scans, a 3-D film could be created so visitors could relive the experience of the escape.

“One of the things that I always say is you leave room for the next generation of technology to do things that you can’t fathom,” Freund said. “Look, I’m doing things that my teachers never thought of. I don’t have the chutzpah to think that I know all the answers, and maybe in another generation the technology will improve, people will have better ideas, you know?”

**********

The escapees spent several months hiding in the forest. In early July, the Red Army, having launched a new offensive against the Germans, encircled Vilnius. Zeidel joined with other partisans to fight alongside the Soviets to liberate the city, and by mid-July the Germans were driven out.

Once the war ended, Zeidel traveled overland before smuggling himself in the autumn of 1945 to what would become the State of Israel. He was among the estimated 60 million people unmoored by the seismic violence of the Second World War. He had no family left: His parents and siblings were presumed killed by the Nazis or their collaborators. In 1948, he married a woman he’d first met, years earlier, in the Jewish ghetto at Vilnius. He died in 2007, in his sleep, the last living member of the Burning Brigade.

This past fall, I reached out to Hana Amir, Zeidel’s daughter, and we spoke several times over Skype. From her home in Tel Aviv, Amir, who is slight and spectacled, with a gray bob, told me about how she learned of her father’s story. When Amir was young, Zeidel worked as a truck driver, and he was gone for long stretches at a time. At home, he was withholding with his daughter and two sons. “My father was of a generation that didn’t talk about their emotions, didn’t talk about how they felt about what they’d been through,” Amir told me. “This was their coping mechanism: If you’re so busy with moving forward, you can disconnect from your memories.” But there were signs that the past wasn’t done with Zeidel: Amir believes he suffered from recurrent nightmares, and he was fastidious about his personal hygiene—he washed his hands many times a day.

When she was 17, Amir took a class about the Holocaust. “How did you escape, Papa?” she remembers asking afterward. He agreed to explain, but what he recounted were mostly technical details: the size of the bunker, the number of bodies consumed by the flames. He explained that in addition to the five men who had fled with him to the Rudnitsky Woods, six other members of the Burning Brigade had survived the escape. The rest had perished.

Over the years, Zeidel’s recalcitrance melted away. In the late 1970s, he sat for interviews with Lanzmann, a few minutes of which were included in the 1985 documentary Shoah. To Lanzmann, Zeidel confided that after his escape, he was sure he stunk of death. Later Zeidel agreed to participate in the making of Out of the Forest, a 2004 Israeli documentary about the role of Lithuanian collaborators in the mass killings at Ponar.

Once a year, on the anniversary of the escape, Zeidel would meet for dinner with Isaac Dogim and David Kantorovich, another member of the Burning Brigade. “The Jews are the strongest people on earth,” Zeidel would say. “Look at what they tried to do to us! And still, we lived.”

Amir told me that Zeidel made several pilgrimages back to Ponar. And yet he was never able to locate the passageway that carried him to freedom. What Zeidel didn’t know was that three years before he died, a Lithuanian archaeologist named Vytautas Urbanavicius had quietly excavated what turned out to be the tunnel’s entrance. But after taking a few photographs and a notebook’s worth of measurements, he sealed up the hole with fresh mortar and stone without pressing any farther or prominently marking the area.

In one of the most affecting scenes from Out of the Forest, Zeidel circles the area of the old bunker, looking for the entrance. “Everything was demolished,” he tells the camera, finally, shaking his head in frustration. “Everything. Not that I care it was demolished, but I was certain there would be an opening, even if a blocked one, so I could show you the tunnel.” As it turned out, Zeidel had been standing very close to the tunnel; he just couldn’t know it.

Last summer, Amir returned home from a trip to the store to find her phone ringing. “Everyone wanted to know if I’d heard about my father,” she recalled. She booted up her computer and found an article about Freund’s work. “I started to shake,” she told me. “I thought, ‘If only he were here with me right now!’”

In a Skype call this fall, Amir cried as she described Zeidel’s final trip to Ponar, in 2002. He’d traveled with Amir and her brother and three of his grandchildren, and the family clustered together near a burial pit.

Cursing in Yiddish and Lithuanian, Zeidel shook his fist at the ghosts of his former Nazi captors. “Can you see me?” Zeidel asked. “I am here with my children, and my children had children of their own, and they are here, too. Can you see? Can you see?”

**********

Walking the grounds of the memorial site, I arrived with Freund at the lip of the pit that had housed the bunker where Zeidel and the other members of the Burning Brigade had lived. The circumference was tremendous, nearly 200 feet in total. On its grassy floor, the Vilna Gaon Museum had erected a model of a double-sided ramp that the Burning Brigade had used to drop bodies onto the pyres.

Freund pointed: On the eastern side of the pit was a slight impression in the wall. It was the entrance to the tunnel.

The tunnel, like the pit, wasn’t marked. Beer cans littered the clearing: Locals used the area to party. Freund kicked at one of the cans and shook his head.

“In any of these circumstances, what you want—the biggest thing you want, the most important—is to be able to make these places visible,” Freund told me later, back in Vilnius. “Your goal is to mark them in a way that people can come to them with tears in their eyes, come to them as memorials, come to them to say the mourner’s kaddish. Because the worst thing would be to look away. To forget.”