How Advertisers Convinced Americans They Smelled Bad

A schoolgirl and a former traveling Bible salesman helped turn deodorants and antiperspirants from niche toiletries into an $18 billion industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Anti-Perspirant-Ads-Men-Gossips-631.jpg)

Lucky for Edna Murphey, people attending an exposition in Atlantic City during the summer of 1912 got hot and sweaty.

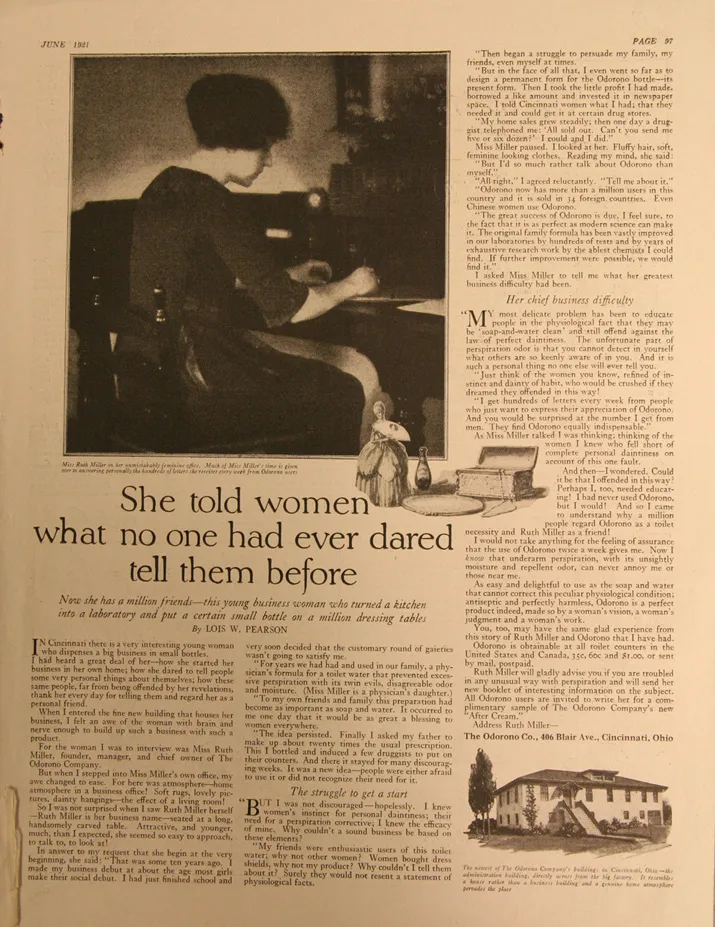

For two years, the high school student from Cincinnati had been trying unsuccessfully to promote an antiperspirant that her father, a surgeon, had invented to keep his hands sweat-free in the operating room.

Murphey had tried her dad’s liquid antiperspirant in her armpits, discovered that it thwarted wetness and smell, named the antiperspirant Odorono (Odor? Oh No!) and decided to start a company.

But business didn’t go well—initially—for this young entrepreneur. Borrowing $150 from her grandfather, she rented an office workshop but then had to move the operation to her parents’ basement because her team of door-to-door saleswomen didn’t pull in enough revenue. Murphey approached drugstore retailers who either refused to stock the product or who returned the bottles of Odorono back, unsold.

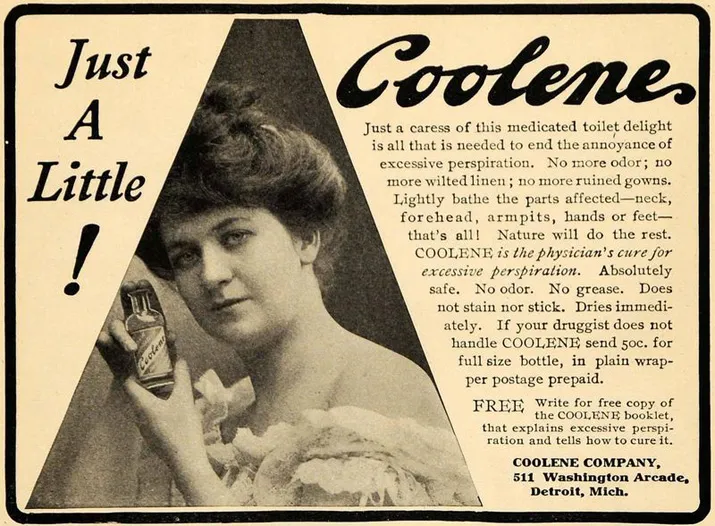

In the 1910s deodorants and antiperspirants were relatively new inventions. The first deodorant, which kills odor-producing bacteria, was called Mum and had been trademarked in 1888, while the first antiperspirant, which thwarts both sweat-production and bacterial growth, was called Everdry and launched in 1903.

But many people—if they had even heard of the anti-sweat toiletries—thought they were unnecessary, unhealthy or both.

“This was still very much a Victorian society,” explains Juliann Silvulka, a 20th-century historian of American advertising at Waseda Univesity in Tokyo, Japan. “Nobody talked about perspiration, or any other bodily functions in public.”

Instead, most people’s solution to body odor was to wash regularly and then to overwhelm any emerging stink with perfume. Those concerned about sweat percolating through clothing wore dress shields, cotton or rubber pads placed in armpit areas which protected fabric from the floods of perspiration on a hot day.

Yet 100 years later, the deodorant and antiperspirant industry is worth $18 billion. The transformation from niche invention to a blockbuster product was in part kick-started by Murphey, whose nascent business was nearly a failure.

According to Odorono company files at Duke University, Edna Murphey’s Odorono booth at the 1912 Atlantic City exposition initially appeared to be another bust for the product.

“The exhibition demonstrator could not sell any Odorono at first and wired back [to Murphey to send some] cold cream to cover expenses,” notes a company history of Odorono.

Luckily, the exposition lasted all summer. As attendees wilted in the heat and sweat through their clothing, interest in Odorono rose. Suddenly Murphey had customers across the country and $30,000 in sales to spend on promotion.

And in reality, Odorono needed some serious help in the marketing department.

Although the product stopped sweat for up to three days—longer-lasting than modern day antiperspirants—the Odorono’s active ingredient, aluminum chloride, had to be suspended in acid to remain effective. (This was the case for all early antiperspirants; it would take a few decades before chemists came up with a formulation that didn’t require an acid suspension.)

The acid solution meant Odorono could irritate sensitive armpit skin and damage clothing. Adding insult to injury, the antiperspirant was also red-colored, so it could also stain clothing—if the acid didn’t eat right through it first. According to company records, customers complained that the product caused burning and inflammation in armpits and that it ruined many a fancy outfit, including one woman’s wedding dress.

To avoid these problems, Odorono customers were advised to avoid shaving prior to use and to swab the product into armpits before bed, allowing time for the antiperspirant to dry thoroughly.

(Deodorants of the era didn’t have the problems with acid formulations, but many, such as Odorono’s main competitor, Mum, were sold as creams which users had to rub into their armpits—an application process many users did not like and which could leave sticky, greasy residues on clothing. In addition, some customers complained that Mum’s early formulation had a peculiar smell.)

Murphey decided to hire a New York advertising agency called J. Walter Thompson Company, who paired her with James Young, a copy writer hired in 1912 to launch the company’s Cincinnati office, where Murphey lived.

Young had once been a door-to-door Bible salesman. He had a high school diploma but no advertising training. He got the copywriter job in 1912 through a childhood friend from Kentucky, who was dating Stanley Resor, a JWT manager who would eventually lead the advertising company. Yet Young would become one of the most famous advertising copy writers of the 20th century, using Odorono as his launching pad.

Young’s early Odorono advertisements focused on trying to combat a commonly held belief that blocking perspiration was unhealthy. The copy pointed out that Odorono (occasionally written Odo-ro-no) had been developed by a doctor and it presented “excessive perspiration” as an embarrassing medical ailment in need of a remedy.

Within a year Odorono sales had jumped to $65,000 and the antiperspirant was being shipped as far as England and Cuba. But after a few years sales had flattened, and by 1919 Young was under pressure to do something different or lose the Odorono contract.

And that’s when Young went radical, and in doing so launched his own fame. A door-to-door survey conducted by the advertising company had revealed that “every woman knew of Odorono and about one-third used the product. But two thirds felt they had no need for [it],” Sivulka says.

Young realized that improving sales wasn’t a simple matter of making potential customers aware that a remedy for perspiration existed. It was about convincing two-thirds of the target population that sweating was a serious embarrassment.

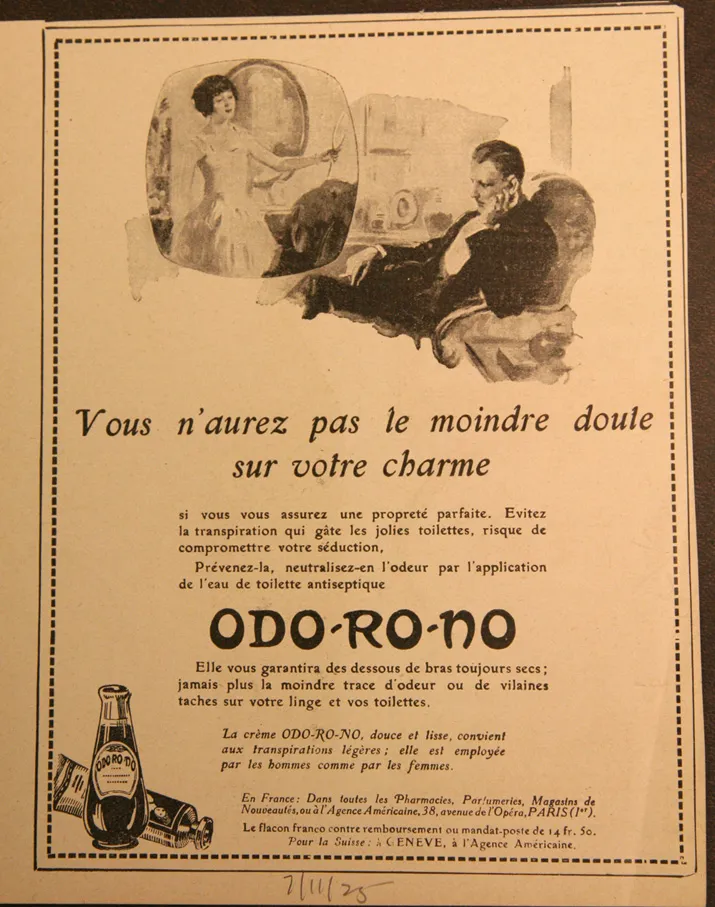

Young decided to present perspiration as a social faux pas that nobody would directly tell you was responsible for your unpopularity, but which they were happy to gossip behind your back about.

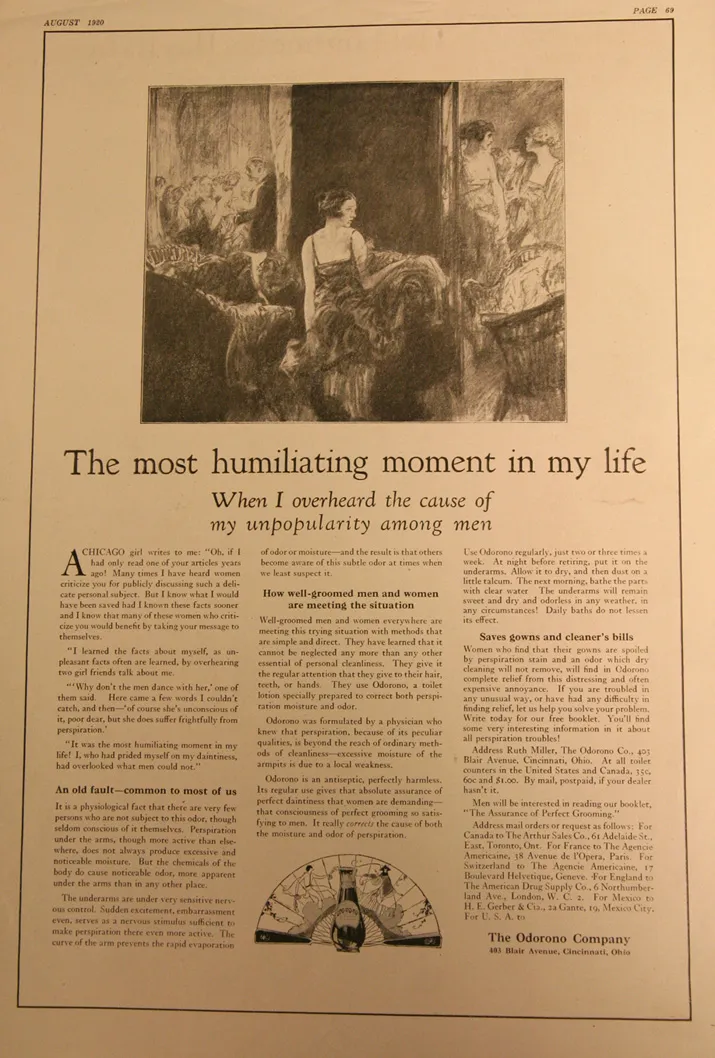

His advertisement in a 1919 edition of the Ladies Home Journal didn’t beat around the bush. “Within the Curve of a Woman’s arm. A frank discussion of a subject too often avoided,” announced the headline above an image of an imminently romantic situation between a man and a woman.

Reading more like a lyrical public service announcement than an advert, Young continued:

A woman’s arm! Poets have sung of it, great artists have painted its beauty. It should be the daintiest, sweetest thing in the world. And yet, unfortunately, it’s isn’t always.

The advertisement goes on to explain that women may be stinky and offensive, and they might not even know it. The take-home message was clear: If you want to keep a man, you’d better not smell.

The advertisement caused shock waves in a 1919 society that still didn’t feel comfortable mentioning bodily fluids. Some 200 Ladies Home Journal readers were so insulted by the advertisement that they canceled their magazine subscription, Sivulka says.

In a memoir, Young notes that women in his social circle stopped speaking to him, while other JWT female copy writers told him “he had insulted every woman in America.” But the strategy worked. According to JWT archives, Odorono sales rose 112 percent to $417,000 in 1920, the following year.

By 1927, Murphey saw her company’s sales reach $1 million dollars. In 1929, she sold the company to Northam Warren, the makers of Cutex, who continued using the services of JWT and Young to promote the antiperspirant.

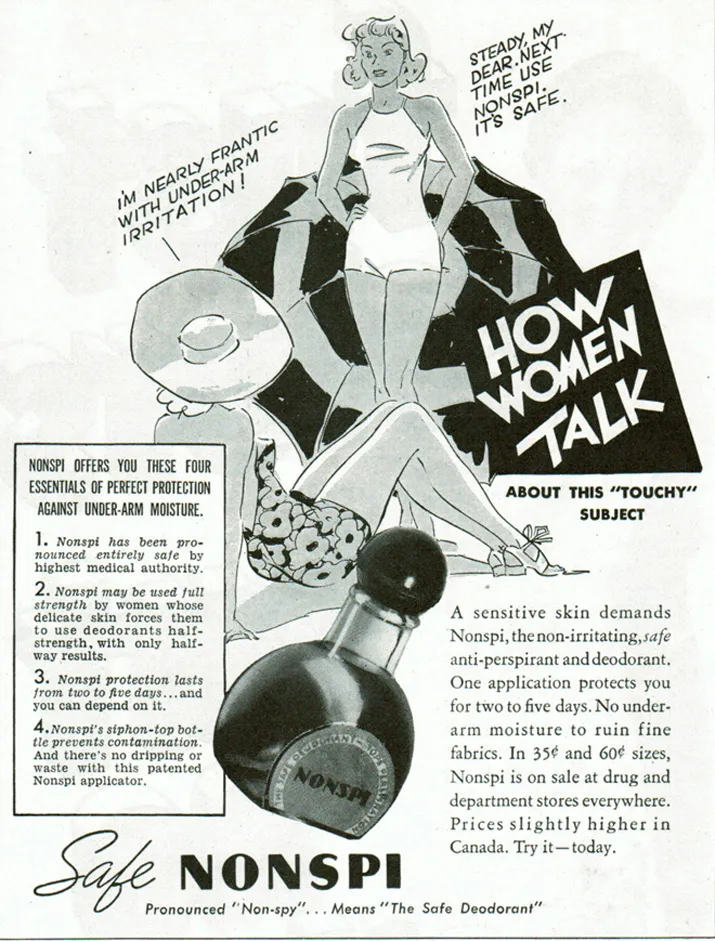

The financial success of Young’s strategy to exploit female insecurity was not lost on competitors. It didn’t take long before other deodorant and antiperspirant companies began to mimic Odorono’s so-called “whisper copy,” to scare women into buying anti-sweat products. (It would take another decade or two before the strategy would be used to get men to buy deodorants and antiperspirants.)

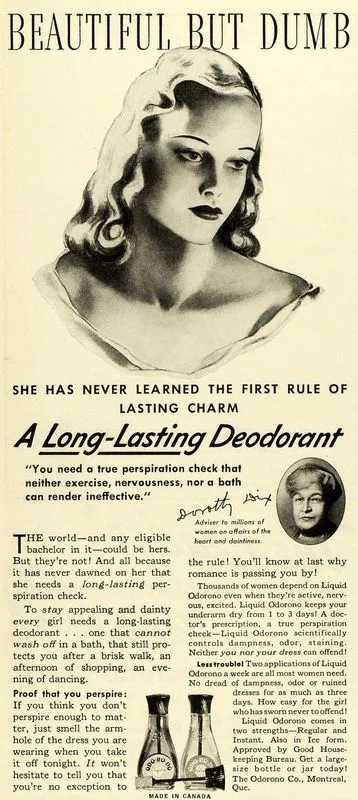

If the 1919 advertisement seemed extreme to some, by the mid 1930s, campaigns were substantially less subtle. “Beautiful but dumb. She has never learned the first rule of long lasting charm,” reads one 1939 Odorono headline, which depicts a morose yet attractive woman who does not wear the anti-sweat product.

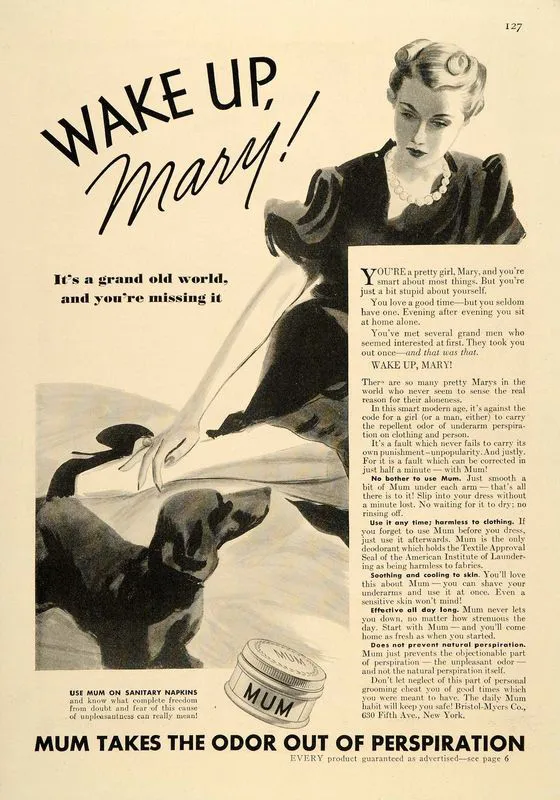

Or consider the 1937 Mum advertisement that speaks to a fictitious woman who does not use deodorant:

You’re a pretty girl, Mary, and you’re smart about most things but you’re just a bit stupid about yourself. You love a good time—but you seldom have one. Evening after evening you sit at home alone. You’ve met several grand men who seemed interested at first. They took you out once—and that was that. There are so many pretty Marys in the world who never seem to sense the real reason for their aloneness. In this smart modern age, it’s against the code for a girl (or a man either) to carry the repellent odor of underarm perspiration on clothing and person. It’s a fault which never fails to carry its own punishment—unpopularity.

The reference to men in the Mum advertisement is a pretty quintessential example of the tentative steps taken by deodorant and antiperspirant companies to begin selling their anti-sweat products to men.

At the beginning of the 20th century, body odor was not considered a problem for men because it was a part of being masculine, explains Cari Casteel, a history doctoral student at Auburn University, who is writing her dissertation on the advertisement of deodorants and antiperspirants to men. “But then companies realized that 50 percent of the market was not using their products.”

Initially copy writers for Odorno, Mum and other products “began adding snarky comments at the end of advertisements targeted to women saying, ‘Women, it’s time to stop letting your men be smelly. When you buy, buy two,’” Casteel says.

A 1928 survey of JWT’s male employees is revealing about that era’s opinions of deodorants and antiperspirants.

“I consider a body deodorant for masculine use to be sissified,” notes one responder. “I like to rub my body in pure grain alcohol after a bath but do not do so regularly,” asserts another.

However the potential profit was not lost on everybody: “I feel there is a market for deodorants among men that is practically unscratched. The copy approach is always directed at women. Why not an intelligent campaign in a leading men’s magazine?”

“If someone like Mennen’s got out a deodorant, men would buy it. Present preparations have a feminine association most men only shy at.”

According to Casteels research, the first deodorant for men was launched in 1935, put in black bottle and called Top-Flite, like the modern, but unrelated golf ball brand.

As with the products for women, advertisers preyed on men’s insecurities: In the Great Depression of the 1930s men were worried about losing their job. Advertisements focused on the embarrassment of being stinky in the office, and how unprofessional grooming could foil your career, she says.

“The Depression shifted the roles of men,” Casteel says. “Men who had been farmers or laborers had lost their masculinity by losing their jobs. Top Flite offered a way to become masculine instantly—or so the advertisement said.” To do so, the products had to distance themselves from their origins as a female toiletry.

For example, Sea-Forth, a deodorant sold in ceramic whiskey jugs starting in the 1940s, “because the company owner Alfred McKelvy said he ‘couldn’t think of anything more manly than whiskey,’” Casteel says.

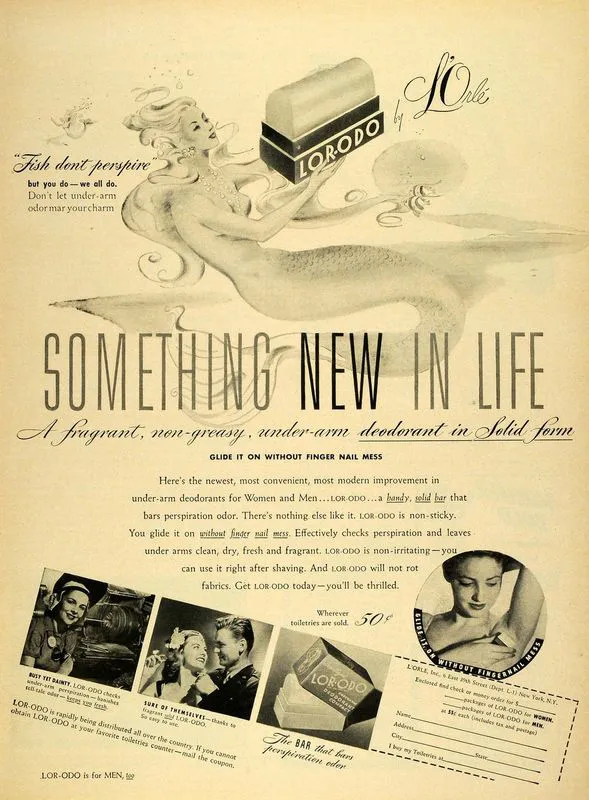

And so anti-sweat products became a part of America’s daily grooming routine for both men and women. A multitude of products flooded the marketplace, with names like, Shun, Hush, Veto, NonSpi, Dainty Dry, Slick, Perstop and Zip—to name just a few. With more companies invested in anti-sweat technology, the decades between 1940 and 1970 saw the development of new delivery systems, such as sticks, roll-ons (based on the ball-point pen), sprays and aerosols, as well as a bounty of newer, sometimes safer, formulations.

Naysayers might argue that western society would have eventually developed its dependence on deodorants and antiperspirants without Murphey and Young, but they certainly left their mark in the armpits of America, as did the heat of New Jersey’s summer of 1912.