How We’ve Commemorated the Civil War

Take a look back at how Americans have remembered the civil war during significant anniversaries of the past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-commemoration-Picketts-charge-631.jpg)

A little over ten years after the start of the Civil War, in July 1871, Gen. George Meade spoke to a reunion of Union Army veterans in Boston.

“Comrades of the Army of the Potomac,” he began, “The first thing I shall do, which we ought to do…is to return our thanks to the Great Being who, in His infinite mercy, has allowed us to be here, to enjoy the pleasures of this meeting, who has blessed us and spared us through all the dangers of the war.”

Reconciliation; unification; a re-examination of the whys and wherefores of the greatest conflict in American history: All of these would be themes of later Civil War reunions and observances, leading up to the current 150th commemoration. What those veterans celebrated in the first major anniversary of the war was the simple fact that they had made it through alive.

“There was a desire among soldiers on both sides to bring moral clarity and purpose to what they had just experienced,” says Peter Carmichael, director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. “We cannot forget that especially for Northern soldiers their celebration of Union meant something deep to them. They went to war to preserve the Union.”

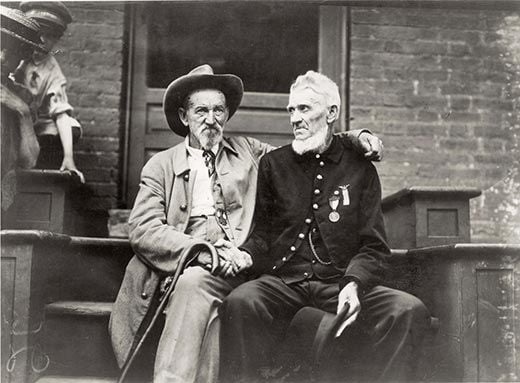

By the time of the 25th anniversary of the war, the veterans of blue and gray were beginning the long process of reconciliation. In 1886, survivors of Confederate Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett’s division were welcomed to a reunion at Gettysburg with Union veterans of the battle from Philadelphia. “Then they were enemies,” wrote the New York Times. “Now they are come together as friends and as citizens of a common country, having no resentments and cherishing no animosities” (At least not in public: “privately,” Carmichael says, “many Confederate veterans were seething over military defeat. There was no question in their mind that the wrong side won the war.”)

Reunification was a dominant theme in the 50th anniversary observances of 1911-1915. George Carr Round, a Union veteran who after the war became a lawyer and settled in Manassas, Virginia, helped organize the Manassas National Jubilee of Peace, in July 1911, in observance of the 50th anniversary of the war’s first battle (also known as Bull Run).

According to historian Joan Zenzen, author of the 1998 book Battling for Manassas—about the preservation of the battlefield—a host of luminaries were on hand for the Peace Jubilee, including President William Howard Taft, who gave the keynote address to an estimated crowd of 10,000 people. As part of the Jubilee, 300 aged Confederates and 125 Federals “marched” up to each other, shook hands, and then joined in “laughter and smiles and backslapping.” For Round, the warm feelings of the Peace Jubilee proved that “hatred, resentments, misunderstandings and injustices” between North and South were “buried, forgotten and forever settled.”

Two years later, an even grander expression of that statement was demonstrated when 55,000 veterans joined hands at Gettysburg.

In 1936, the 75th anniversary of the war, we see the first example of a new phenomenon: The Civil War reenactment, as the Battle of Bull Run was refought on the actual site, although not by enthusiasts studiously attired in period garb, but 1,500 U.S. soldiers and Marines of 1936, who were ordered to fight like it was 1861. The 75th anniversary was held in the midst of the Great Depression—and the forces of the New Deal were marshaled on the Manassas battlefield, as well. According to national parks historian John Reid, hundreds of workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps worked to prepare the battlefield for the reenactment and served as ushers to the surprisingly large crowd of 31,000 spectators—only 5,000 of whom were able to be seated in the wooden stand constructed by the CCC and the National Park Service for the event.

The culmination of the 75th anniversary was the Gettysburg encampment on Independence Day weekend 1938. President Franklin Roosevelt addressed 1,800 veterans (most of them in their 90s) in what was billed as the “last reunion.” The high point of that weekend featured hundreds of U.S. tanks rolling across the battlefield, followed by a simulated air assault on the town of Gettysburg. The old veterans reportedly cheered the display of modern military technology.

By 1961, all living participants in the Civil War had passed away, but interest in the conflict was growing. In the previous decade, the emergence of Civil War Round Tables had created a cadre of eager history buffs and enthusiasts; tourism at battlefields was up and popular histories on the war by writers such as Bruce Catton had become best sellers. According to historian Robert J. Cook—whose 2007 book Troubled Commemoration looks at the 1961-1965 centennial—an opportunity was seen to create what he calls an “ambitious Cold War pageant” overseen by a federal commission. It fizzled, however—largely because of what Cook considers an overcommercialized approach, as well as organizers’ “readiness to allow white segregationists to turn the event into a heavily politicized celebration of the Confederacy at a time when Jim Crow institutions and customs were coming under increasing attack.”

The centennial, begun with high hopes for success, ended with what Cook calls “a suitably dull ceremony held under lowering skies at Appomattox Court House in April 1965.” In a country distracted by a growing war in Vietnam, there was little media attention given to the 100th anniversary re-enactment of the surrender that marked the Civil War’s end.

How the 150th will unfold remains to be seen. Many exhibitions and events being staged for the sesquicentennial in various states and cities offer previously overlooked perspectives of the war—including those of African-Americans, civilians and Native Americans, who are getting long overdue recognition.

Still, Carmichael says, “There’s a tension we see in commemorative activities by soldiers who fought that war, and that persists to this day. That is, how do you convey the brutal reality of the Civil War, without sacrificing some of the higher ideas that sustained these men throughout this conflict?”