The Injustice of Japanese-American Internment Camps Resonates Strongly to This Day

During WWII, 120,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into camps, a government action that still haunts victims and their descendants

Jane Yanagi Diamond taught American History at a California high school, “but I couldn’t talk about the internment,” she says. “My voice would get all strange.” Born in Hayward, California, in 1939, she spent most of World War II interned with her family at a camp in Utah.

Seventy-five years after the fact, the federal government’s incarceration of some 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent during that war is seen as a shameful aberration in the U.S. victory over militarism and totalitarian regimes. Though President Ford issued a formal apology to the internees in 1976, saying their incarceration was a “setback to fundamental American principles,” and Congress authorized the payment of reparations in 1988, the episode remains, for many, a living memory. Now, with immigration-reform proposals targeting entire groups as suspect, it resonates as a painful historical lesson.

The roundups began quietly within 48 hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941. The announced purpose was to protect the West Coast. Significantly, the incarceration program got underway despite a warning; in January 1942, a naval intelligence officer in Los Angeles reported that Japanese-Americans were being perceived as a threat almost entirely “because of the physical characteristics of the people.” Fewer than 3 percent of them might be inclined toward sabotage or spying, he wrote, and the Navy and the FBI already knew who most of those individuals were. Still, the government took the position summed up by John DeWitt, the Army general in command of the coast: “A Jap’s a Jap. They are a dangerous element, whether loyal or not.”

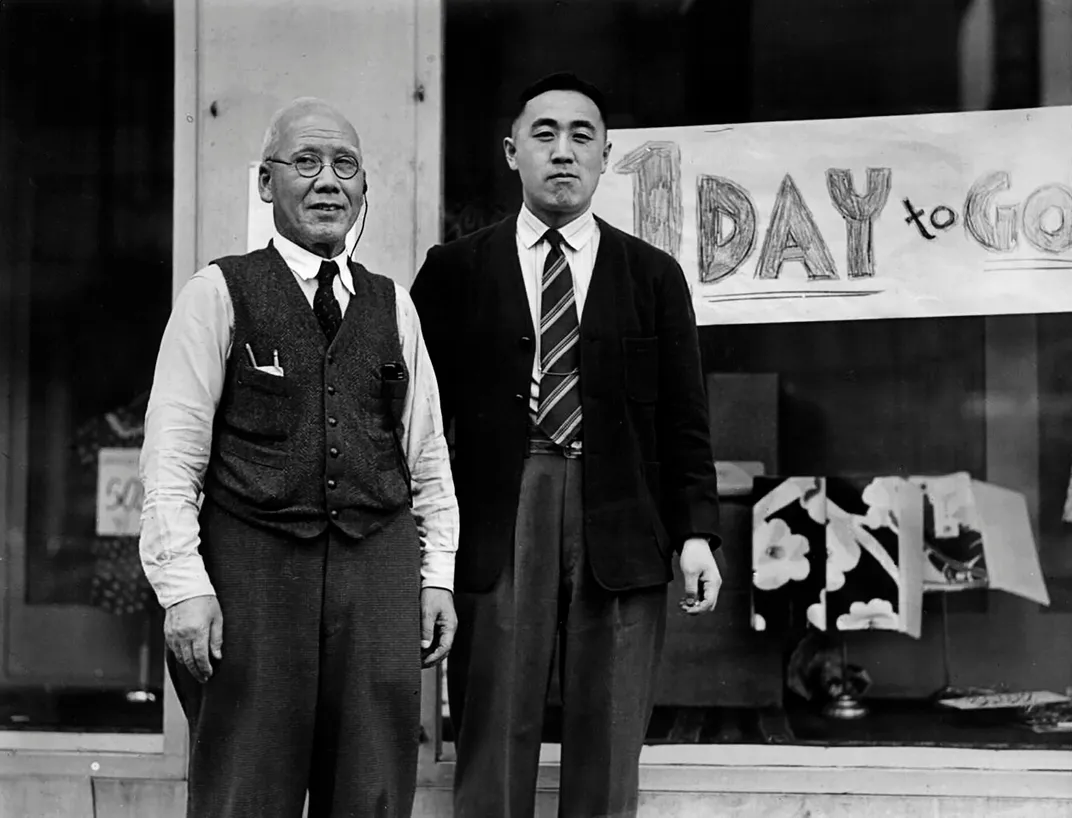

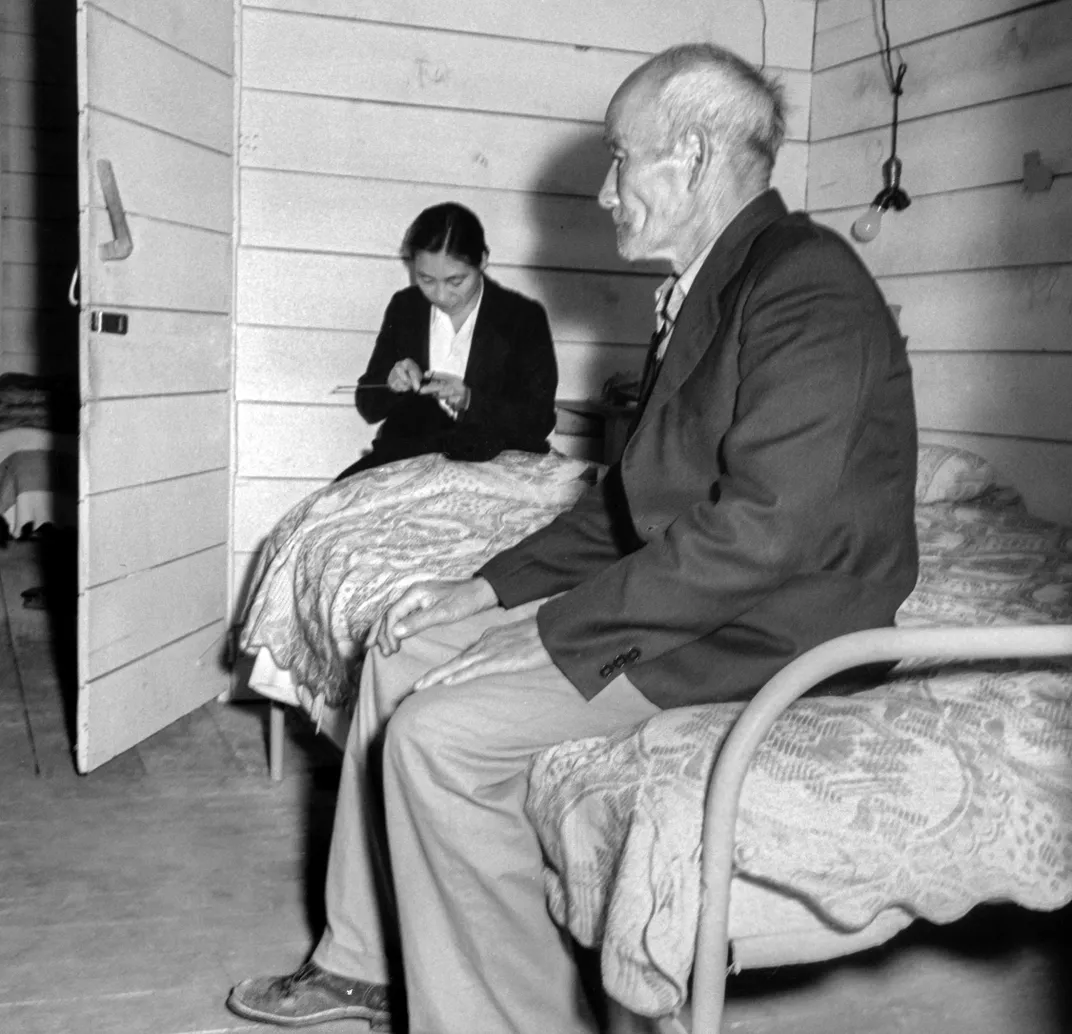

That February, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, empowering DeWitt to issue orders emptying parts of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona of issei—immigrants from Japan, who were precluded from U.S. citizenship by law—and nisei, their children, who were U.S. citizens by birth. Photographers for the War Relocation Authority were on hand as they were forced to leave their houses, shops, farms, fishing boats. For months they stayed at “assembly centers,” living in racetrack barns or on fairgrounds. Then they were shipped to ten “relocation centers,” primitive camps built in the remote landscapes of the interior West and Arkansas. The regime was penal: armed guards, barbed wire, roll call. Years later, internees would recollect the cold, the heat, the wind, the dust—and the isolation.

There was no wholesale incarceration of U.S. residents who traced their ancestry to Germany or Italy, America’s other enemies.

The exclusion orders were rescinded in December 1944, after the tides of battle had turned in the Allies’ favor and just as the Supreme Court ruled that such orders were permissible in wartime (with three justices dissenting, bitterly). By then the Army was enlisting nisei soldiers to fight in Africa and Europe. After the war, President Harry Truman told the much-decorated, all-nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team: “You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice—and you have won.”

If only: Japanese-Americans met waves of hostility as they tried to resume their former lives. Many found that their properties had been seized for nonpayment of taxes or otherwise appropriated. As they started over, they covered their sense of loss and betrayal with the Japanese phrase Shikata ga nai—It can’t be helped. It was decades before nisei parents could talk to their postwar children about the camps.

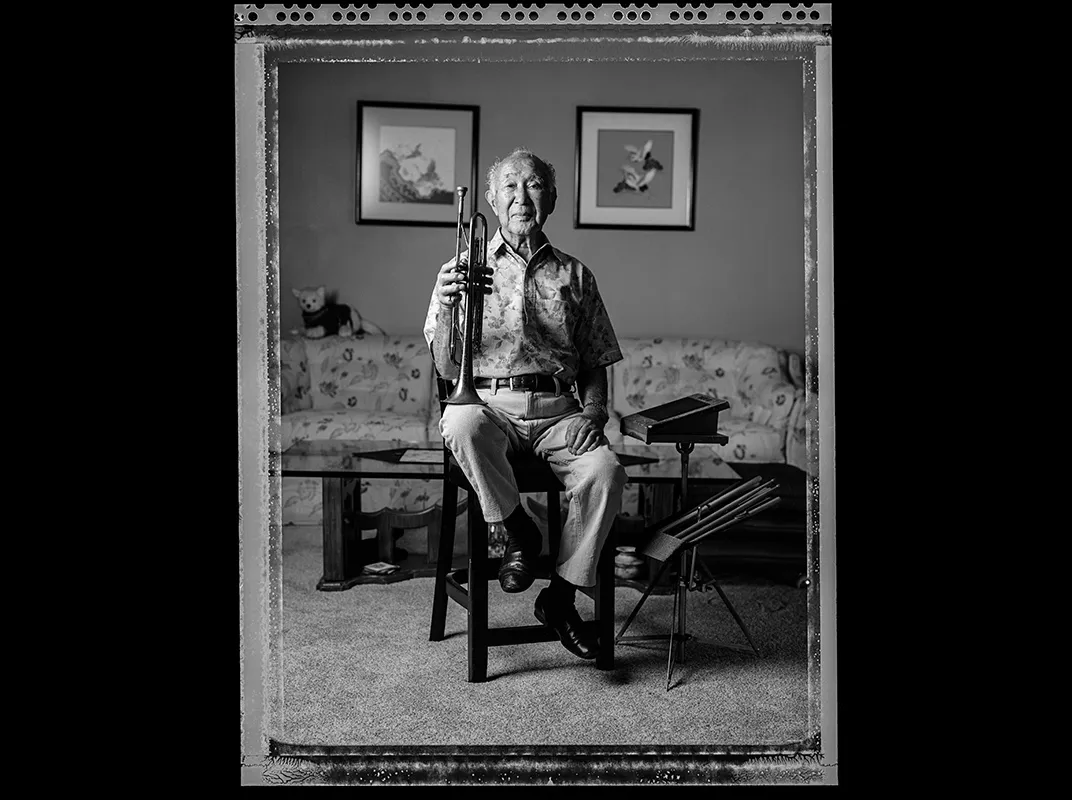

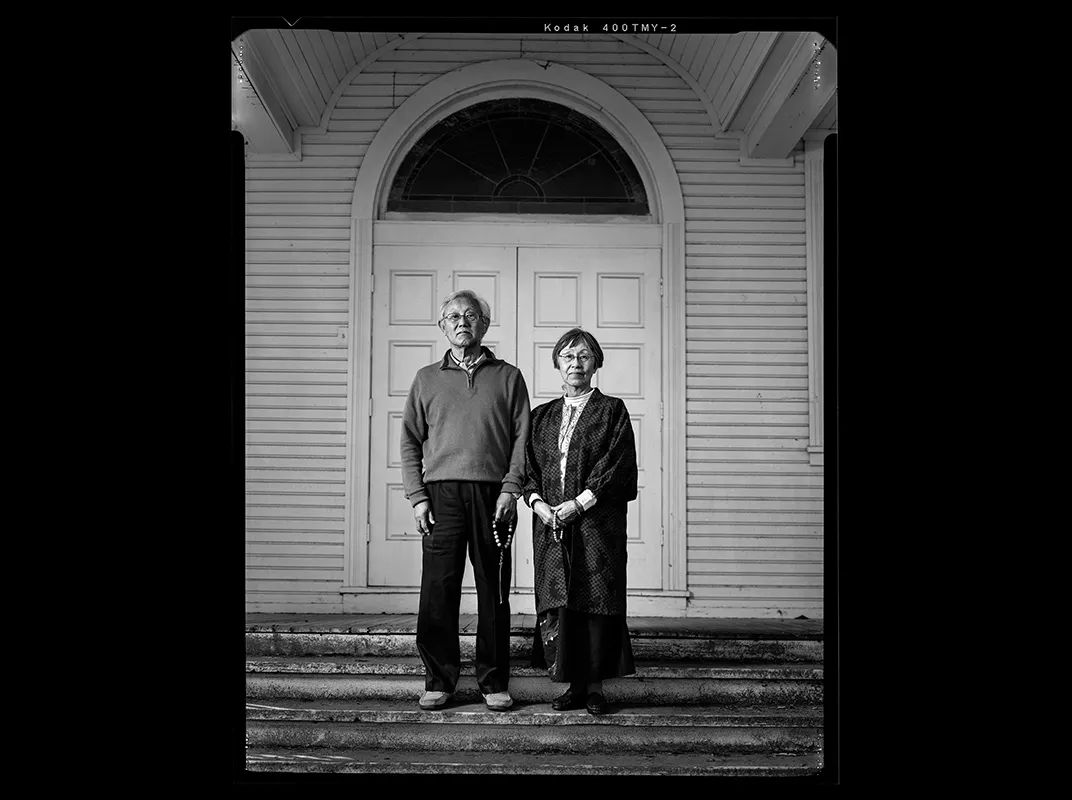

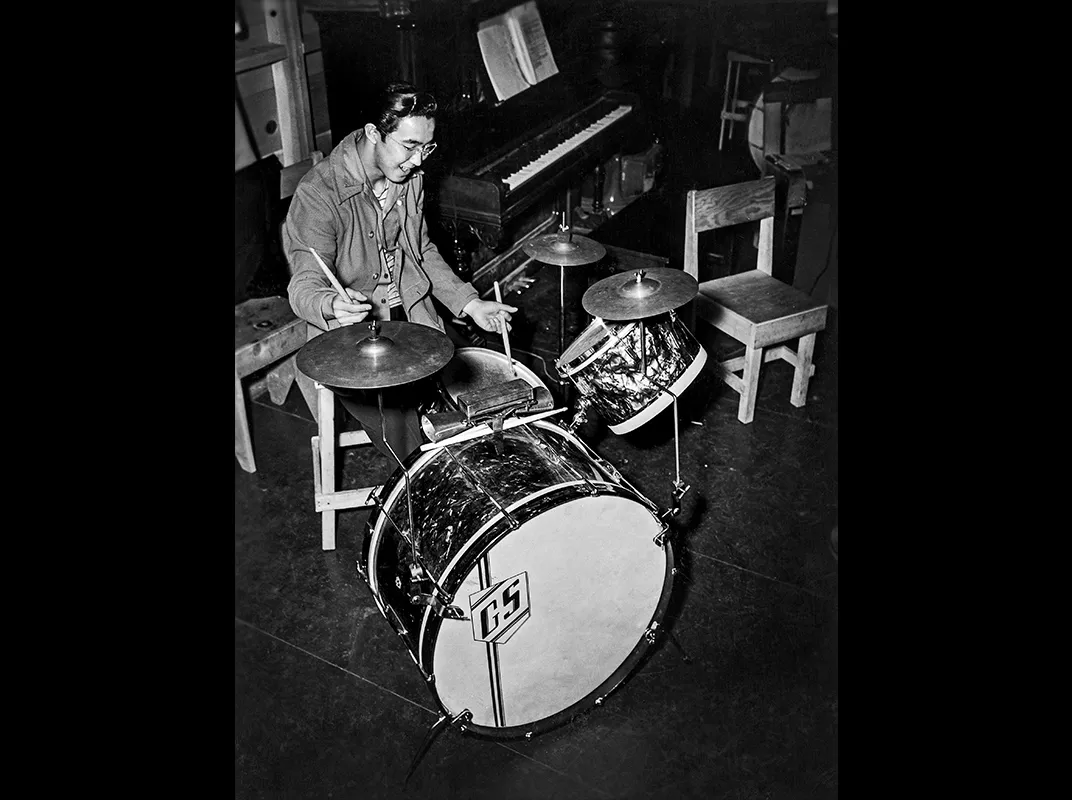

Paul Kitagaki Jr., a photojournalist who is the son and grandson of internees, has been working through that reticence since 2005. At the National Archives in Washington, D.C., he has pored over more than 900 pictures taken by War Relocation Authority photographers and others—including one of his father’s family at a relocation center in Oakland, California, by one of his professional heroes, Dorothea Lange. From fragmentary captions he has identified more than 50 of the subjects and persuaded them and their descendants to sit for his camera in settings related to their internment. His pictures here, published for the first time, read as portraits of resilience.

Jane Yanagi Diamond, now 77 and retired in Carmel, California, is living proof. “I think I’m able to talk better about it now,” she told Kitagaki. “I learned this as a kid—you just can’t keep yourself in gloom and doom and feel sorry for yourself. You’ve just got to get up and move along. I think that’s what the war taught me.”

Subject interviews conducted by Paul Kitagaki Jr.

Related Reads

Impounded

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/27/1b27ce17-ef7e-47bb-901e-1a1cc28bc4e1/janfeb2017_k10_japaneseinternmentcamps.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/e7/0fe74f75-550c-4016-9631-7710aed1eb95/janfeb2017_k01_japaneseinternmentcamps.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)