For More Than 100 Years, the U.S. Forced Navajo Students Into Western Schools. The Damage Is Still Felt Today

Photographer Daniella Zalcman explores how native populations had a new nation foisted upon them

At the beginning of Navajo time, the Holy People (Diyin Dine’é) journeyed through three worlds before settling in Dinétah, our current homeland. Here they took form as clouds, sun, moon, trees, bodies of water, rain and other physical aspects of this world. That way, they said, we would never be alone. Today, in the fourth world, when a Diné (Navajo) baby is born, the umbilical cord is buried near the family home, so the child is connected to its mother and the earth, and will not wander as if homeless.

In 1868, five years after the U.S. government forcibly marched the Diné hundreds of miles east from their ancestral lands in Arizona and New Mexico and imprisoned them at Fort Sumner, an act of brutality we know as Hwéeldi, or “the time of overwhelming grief,” a treaty was signed that delineated the borders of present-day Dinétah: 27,000 square miles in New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, and three smaller reservations in New Mexico at Ramah, Alamo and Tohajiilee. The treaty brought devastating changes, including compulsory education for children, who were sent to faraway government and missionary schools.

For Diné families, sustained by kinship and clan connections that emphasized compassion, love and peacefulness, the separation was all but unendurable. It threatened our very survival, as it was intended to do. Our language—which retains our timeless traditions and embodies our stories, songs and prayers—eroded. Ceremonial and ritual ties weakened. The schools followed military structure and discipline: Children were divided into “companies,” issued uniforms and marched to and from activities. Their hair was cut or shaved. Because speaking Navajo was forbidden, many children did not speak at all. Some disappeared or ran away; many never returned home.

As a child at a mission boarding school in the 1960s, I was forced to learn English. Nowhere in our lessons was there any mention of Native history. But at night, after lights out, we girls gathered in the dark to tell stories and sing Navajo songs, quietly, so as to not wake the housemother. We were taught that if we broke the rules, we would go to hell, a place we could not conceive of—there is no Navajo analogy. As I learned to read, I discovered in books a way to assuage my longing for my parents, my siblings, my home. So in this way my schooling was a mixed experience, a fact that was true for many Native children.

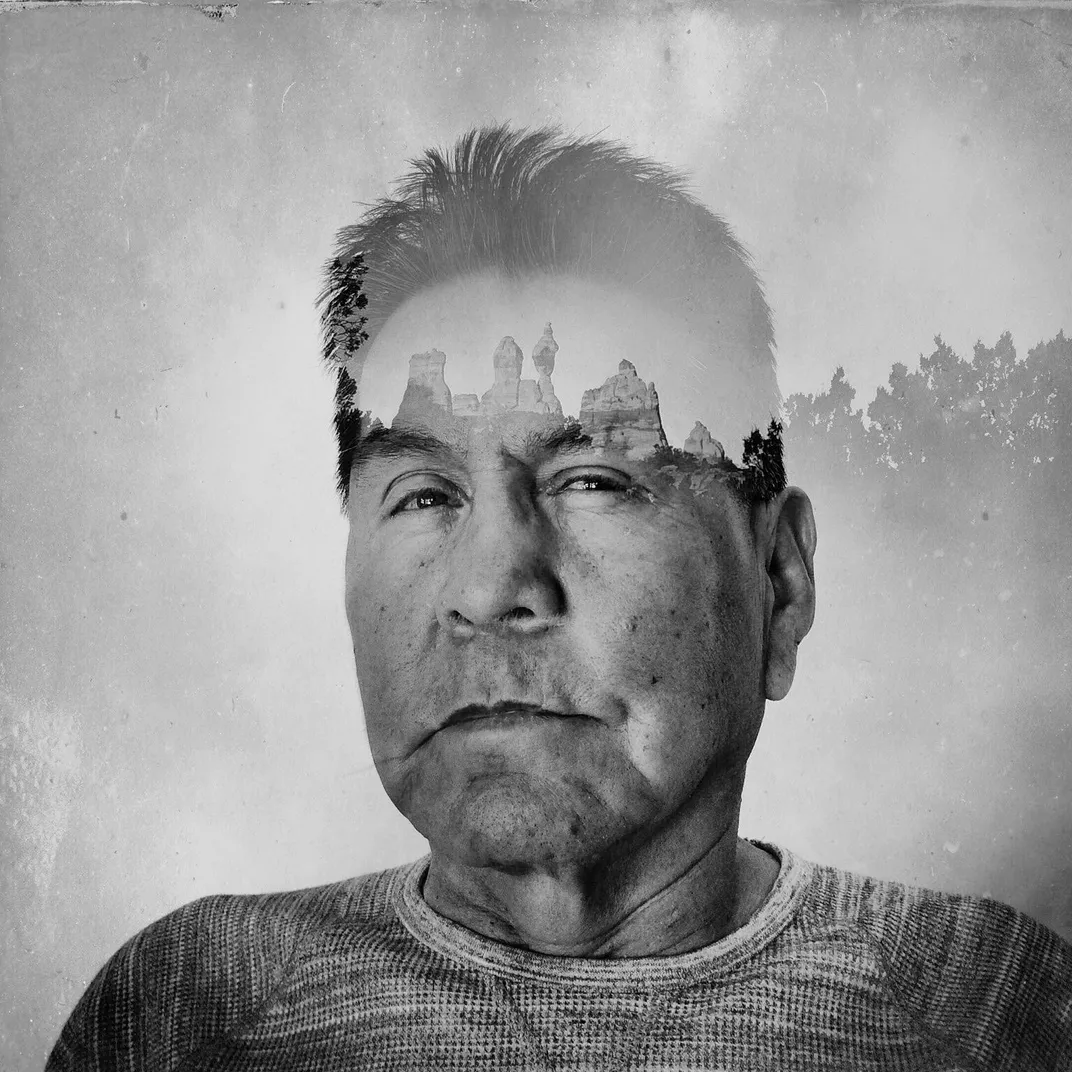

The stories of former students are captured in striking images by the photographer Daniella Zalcman, who uses multiple digital exposures to layer portraits atop landscapes with special meaning—the abandoned interior of a shuttered dormitory, a church atop a desolate hill. Today those students are parents and grandparents. Many hold onto a lingering homesickness and sense of alienation. Others are beset by nightmares, paranoia and a deep distrust of authority.

In time, injustices in the school system came under public scrutiny. The 1928 Meriam Report stated “frankly and unequivocally that the provisions for the care of Indian children in boarding schools are grossly inadequate.” Almost half a century later, a 1969 Senate report constituted, in the words of its authors, “a major indictment of our failure.” The report’s hundreds of pages were not enough to tell the story, the authors wrote, of “the despair, the frustration, the hopelessness, the poignancy...of families which want to stay together but are forced apart.”

Real reform began after the passage of the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, though it would be several years before widespread changes would take hold. But by 1990, when Congress enacted a law to protect Native languages, tribal involvement in education had become the norm. Some boarding schools were shut down. Others operate to this day but are mainly community, or tribal, run. No longer are they designed to eliminate Native culture. Diné language is now taught alongside English. Navajo history and culture are embedded in the curriculum.

As a poet and professor of English, I conceive of my work in Navajo and translate it into English, drawing on the rich visual imagery, metaphorical language and natural cadences of my first language. My daughter, an educator herself, not long ago moved into my parents’ old house, in Shiprock, New Mexico, when she got a job at nearby Diné College. Our children, once taken from Dinétah, have returned home.

Daniella Zalcman's photography was supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

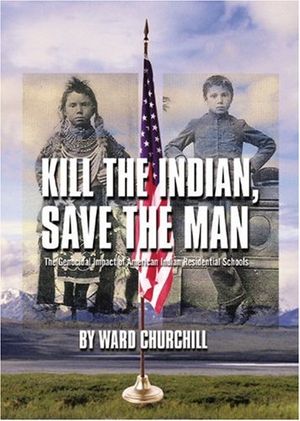

Kill the Indian, Save the Man