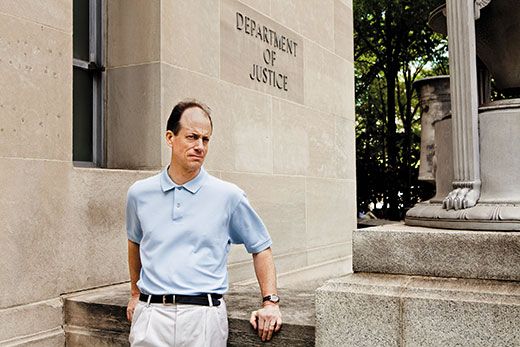

Leaks and the Law: The Story of Thomas Drake

The former NSA official reached a plea deal with the government, but the case still raises questions about the public’s right to know

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Drake-Department-of-Justice-631.jpg)

Editor's Note: This article was updated from the version in the July/August 2011 issue of the printed magazine to reflect Thomas Drake's June 9 plea agreement and his July 15 sentencing.

Thomas A. Drake was a senior executive at the National Security Agency for seven years. When his efforts to alert his superiors and Congress to what he saw as illegal activities, waste and mismanagement at the NSA led nowhere, he decided to take his allegations to the press. Although he was cautious—using encrypted e-mail to communicate with a reporter—his leak was discovered. Last year the government indicted Drake under the Espionage Act. If convicted, he would have faced up to 35 years in prison.

The Drake case loomed as the biggest leak prosecution since the trial of Daniel Ellsberg four decades ago. The indictment against him included not only five counts of violating the Espionage Act, but also one charge of obstruction of justice and four counts of making false statements to the FBI while he was under investigation. Drake, who resigned from the NSA under pressure in 2008, has been working in recent months at an Apple computer store outside Washington, D.C., answering questions from customers about iPhones and iPads.

He was to be tried in Baltimore on June 13, but the trial was averted four days earlier. After key rulings on classified evidence went against the prosecutors, they struck a plea agreement: in exchange for Drake’s pleading guilty to one count of exceeding the authorized use of a government computer, they dropped all the original charges and agreed not to call for prison time. On July 15, he was sentenced to one year of probation and 240 hours of community service.

Despite that outcome, the Drake case will have broad implications for the relationship between the government and the press. And it did not settle the broader question that overshadowed the proceedings: Are employees of sensitive agencies like the NSA, the CIA and the FBI who leak information to the news media patriotic whistleblowers who expose government abuses—or lawbreakers who should be punished for endangering national security? The question is becoming only more complicated in an age marked by unprecedented flows of information and the threat of terrorism.

As president-elect, Barack Obama took the position that whistleblowing by government employees was an act “of courage and patriotism” that “should be encouraged rather than stifled.” But Drake’s indictment was only one in an extraordinary string of leak investigations, arrests and prosecutions undertaken by the Obama administration.

In May 2010, Pfc. Bradley Manning was arrested and charged with leaking more than 250,000 State Department cables and thousands of intelligence reports to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Manning, a 23-year-old Army intelligence analyst, is in military custody, charged with aiding the enemy, publishing intelligence on the Internet, multiple theft of public records and fraud. Although aiding the enemy is a capital offense, Army prosecutors have said they will not recommend the death penalty. If convicted, Manning could be sent to prison for life. His trial has not been scheduled.

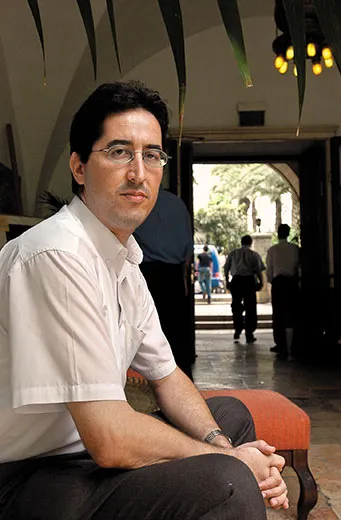

Also in May 2010, Shamai K. Leibowitz of Silver Spring, Maryland, a 39-year-old Israeli-American who worked on contract for the FBI as a Hebrew linguist, was sentenced to 20 months in prison after pleading guilty to leaking classified documents to a blogger.

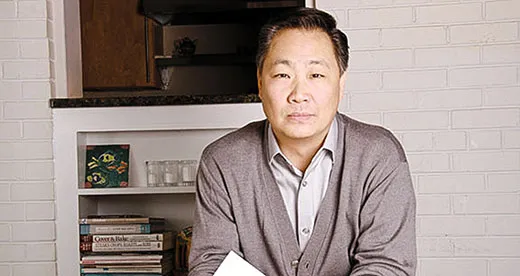

Last August, Stephen Jin-Woo Kim, 43, a senior adviser for intelligence on contract to the State Department, was charged with leaking defense data. Although the indictment did not spell out any details, news media reported that Kim had provided information to Fox News, which aired a story saying the CIA had warned that North Korea would respond to U.N. sanctions with another nuclear weapons test. His trial also remains unscheduled.

And in January of this year, Jeffrey A. Sterling, 43, a former CIA employee, was arrested and charged with leaking defense information to “an author employed by a national newspaper,” a description that pointed to reporter James Risen of the New York Times. In his 2006 book, State of War, Risen disclosed a failed CIA operation, code-named Merlin, in which a former Russian nuclear scientist who had defected to the United States was sent to Iran with a design for a nuclear weapons device. The blueprint contained a flaw meant to disrupt the Iranian weapons program. Certain that Iranian experts would quickly spot the flaw, the Russian scientist told them about it. The indictment of Sterling, in circumspect language, says in effect that he had been the Russian’s case officer. His trial was scheduled for September 12.

According to Jesselyn A. Radack of the Government Accountability Project, a whistleblower advocacy organization, the Obama administration “has brought more leak prosecutions than all previous presidential administrations combined.” Radack, a former Justice Department attorney, was herself a whistleblower, having told a reporter in 2002 that FBI interrogators violated the right of American terrorism suspect John Walker Lindh to have an attorney present during questioning. (Lindh later pleaded guilty to two charges and is serving a 20-year prison sentence.) Radack introduced Drake at a reception at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. this past April, at which he received the Ridenhour Prize for Truth-Telling. The $10,000 award is named for Ron Ridenhour, the Vietnam veteran who in 1969 wrote to Congress, President Richard M. Nixon and the Pentagon in an attempt to expose the killing of civilians in the Vietnamese village of My Lai the previous year; the massacre was later brought to light by reporter Seymour Hersh.

“I did not take an oath to support and defend government illegalities, violations of the Constitution or turn a blind eye to massive fraud, waste and abuse,” Drake said in accepting the award, his first public comment on his case. (He declined to be interviewed for this article.) His oath to defend the Constitution, he said, “took precedence...otherwise I would have been complicit.”

The Justice Department has taken a different view. When Drake was indicted, Assistant Attorney General Lanny A. Breuer issued a statement saying, “Our national security demands that the sort of conduct alleged here—violating the government’s trust by illegally retaining and disclosing classified information—be prosecuted and prosecuted vigorously.”

Drake’s case marked only the fourth time the government had invoked the espionage laws to prosecute leakers of information related to national defense.

The first case was that of Daniel Ellsberg, who in 1971 leaked the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the Vietnam War, to the New York Times. Two years later, Judge William Byrne Jr. dismissed the charges against Ellsberg due to “improper government conduct,” including tapping Ellsberg’s telephone and breaking into his psychiatrist’s office in search of damaging information about him. The Nixon White House also tried to suborn Judge Byrne, offering him the job of FBI director while he was presiding over the trial.

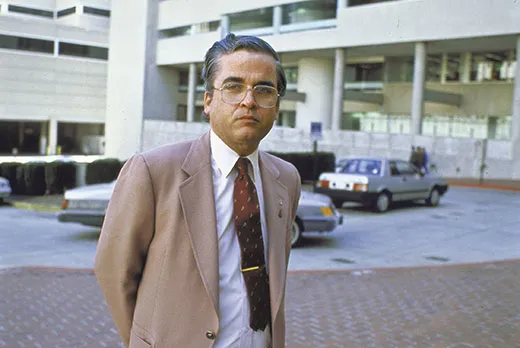

Next came the Reagan administration’s prosecution of Samuel Loring Morison, a Navy intelligence analyst convicted in 1985 and sentenced to two years in prison for leaking—to Jane’s Defence Weekly, the British military publication—three satellite photos of a Soviet ship under construction. After Morison was released from prison, he was pardoned by President Bill Clinton.

And in 2005, the Bush administration charged Lawrence A. Franklin, a Pentagon official, with leaking classified information on Iran and other intelligence to two employees of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, the pro-Israel lobby. Franklin was convicted and sentenced to more than 12 years in prison, but in 2009 that was reduced to probation and ten months in a halfway house after the Obama administration dropped its case against the two AIPAC officials.

Tom Drake, who is 54, married and the father of five sons, worked in intelligence for most of his adult life. He volunteered for the Air Force in 1979 and was assigned as a cryptologic linguist working on signals intelligence—information derived from the interception of foreign electronic communications—and flying on spy planes that scoop up such data. He later worked briefly for the CIA. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1986 from the University of Maryland’s program in Heidelberg, Germany, and in 1989 a master’s degree in international relations and comparative politics from the University of Arizona. Beginning in 1989, he worked for several NSA contractors until he joined the agency as a senior official in the Signals Intelligence Directorate at the agency’s headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland. His first day on the job was September 11, 2001.

The NSA, which is so secretive that some joke its initials stand for “No Such Agency,” collects signals intelligence across the globe from listening platforms under the sea, in outer space, in foreign countries, on ships and on aircraft. Technically part of the Defense Department, it receives a sizable chunk of the $80 billion annual U.S. intelligence budget and has perhaps 40,000 employees, although its exact budget and size are secret. In addition to collecting electronic intelligence, the agency develops U.S. codes and tries to break the codes of other countries.

Despite the NSA’s secrecy, it was widely reported that the agency has had great difficulty keeping up with the vast pools of data it collected—billions of e-mails sent daily; text and voice messages from cell phones, some of which are encrypted; and the millions of international telephone calls that pass through the United States each day.

Developing the ability to cull intelligence from so much data became even more critical after 9/11. With the secret authorization of President George W. Bush, Air Force Gen. Michael V. Hayden, then the NSA director, initiated a program of intercepting international phone calls and e-mails of people in the United States without a warrant to do so. The program was launched even though the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) provided for a special court to approve wiretap warrants and the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. The Bush administration said it relied on the president’s constitutional power as commander in chief of the armed forces when it authorized the secret eavesdropping. It also said the wiretapping was justified by a Congressional resolution passed after 9/11 authorizing the president to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against those responsible for the attacks.

The warrantless wiretapping was disclosed in 2005 by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau of the New York Times. They received a Pulitzer Prize for their reporting, and the government began investigating the source of the leak. Several months after the Times wiretapping story appeared, USA Today disclosed that the NSA was collecting the records of billions of domestic telephone calls with the cooperation of major telecommunications companies. (A 2008 revision of the FISA law has expanded the executive branch’s authority to conduct electronic surveillance and reduced court review of some operations.)

Drake’s troubles began when he became convinced that an NSA program intended to glean important intelligence, code-named Trailblazer, had turned into a boondoggle that cost more than a billion dollars and violated U.S. citizens’ privacy rights. He and a small group of like-minded NSA officials argued that an alternate program, named ThinThread, could sift through the agency’s oceans of data more efficiently and without violating citizens’ privacy. (ThinThread cloaked individual names while allowing their identification if necessary.) Drake has said that if the program had been fully deployed, it would likely have detected intelligence related to Al Qaeda’s movements before 9/11.

When Drake took his concerns to his immediate boss, he was told to take them to the NSA inspector general. He did. He also testified under subpoena in 2001 before a House intelligence subcommittee and in 2002 before the joint Congressional inquiry on 9/11. He spoke to the Defense Department’s inspector general as well. To him it seemed that his testimony had no effect.

In 2005, Drake heard from Diane Roark, a former Republican staff member on the House intelligence committee who had monitored the NSA. According to the indictment of Drake, Roark, identified only as Person A, “asked defendant Drake if he would speak to Reporter A,” an apparent reference to Siobhan Gorman, then a Baltimore Sun reporter covering intelligence agencies. Roark says she didn’t. “I never urged him to do it,” she said in an interview. “I knew he could lose his job.”

In any case, Drake contacted Gorman, and they subsequently exchanged encrypted e-mails, according to the indictment. At a court hearing in March, defense attorneys confirmed that Drake had given Gorman two documents, but said Drake believed they were unclassified. (Gorman, now with the Wall Street Journal, declined to comment for this article.)

In 2006 and 2007, Gorman wrote a series of articles for the Sun about the NSA, focusing on the intra-agency controversy over Trailblazer and ThinThread. Her stories, citing several sources and not naming Drake, reported that Trailblazer had been abandoned because it was over budget and ineffective.

In November 2007, federal agents raided Drake’s house. He has said they questioned him about the leak to the New York Times regarding warrantless wiretapping and that he told them he had not spoken to the Times. He has also said he told them he provided unclassified information about Trailblazer to the Sun. The government’s investigation continued, and in April 2010 a federal grand jury in Baltimore issued the indictment against him.

Drake was not charged with classic espionage—that is, spying for a foreign power. (The word “espionage,” in fact, appears only in the title of the relevant section of the U.S. Code, not in the statutes themselves.) Rather, the five counts under the Espionage Act accused him of “willful retention of national defense information”—the unauthorized possession of documents relating to the national defense and failure to return them to officials entitled to receive them.

Understanding these charges requires a short course in U.S. espionage law. Congress passed the original Espionage Act on June 15, 1917—two months after the United States entered World War I—and President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law the same day. There was no formal system for classifying nonmilitary information until President Harry Truman established one, by executive order, in September 1951. With the exception of information dealing with codes and communications intelligence, the language of the espionage laws refers not to classified documents per se, but to information “relating to the national defense”—a broader category.

In practice, prosecutors are usually reluctant to bring a case under the espionage laws unless they can show that a defendant has revealed classified information; jurors might be reluctant to conclude that the release of unclassified information has harmed national security. But in Drake’s case, the government was careful to say that the documents he allegedly leaked were related, in the language of the statute, “to the national defense.”

The point was highlighted at a pre-trial hearing this past March 31, when Drake’s attorneys—public defenders Deborah L. Boardman and James Wyda—produced a two-page document described in the indictment as “classified” that was clearly stamped “unclassified.”

Judge Richard D. Bennett turned to the government attorneys. “Your position on this is that, despite an error with respect to that particular document having ‘Unclassified’ stamped on it, it still related to the national defense...?”

“Yeah, that’s right,” replied Assistant U.S. Attorney William M. Welch II, according to a transcript of the hearing. Bennett then denied a defense motion to dismiss the count of the indictment relating to the document in question. In subsequent rulings, however, Bennett said the prosecution could not substitute unclassified summaries of classified evidence during the trial, severely limiting the government’s case.

In his Ridenhour Prize acceptance speech, Drake insisted that the government’s prosecution was intent “not on serving justice, but on meting out retaliation, reprisal and retribution for the purpose of relentlessly punishing a whistleblower,” and on warning potential whistleblowers that “not only can you lose your job but also your very freedom.” Dissent, he added, “has become the mark of a traitor.... as an American, I will not live in silence to cover for the government’s sins.”

Strong words, but Drake’s case raises another question. Why has the Obama administration pursued so many leakers?

All presidents abhor leaks. They see leaks as a challenge to their authority, as a sign that people around them, even their closest advisers, are talking out of turn. There will be no more “blabbing secrets to the media,” James Clapper warned in a memo to personnel when he took over as President Obama’s director of national intelligence last year. Of course, some leaks may interfere with the execution of government policy, or indeed harm national security.

Lucy A. Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, says the Obama administration “is clearly making a point of going after people who have access to sensitive and classified information. They are aggressively pursuing government employees who have access to that information and release it to journalists.” Technology has made the job of government investigators much easier, she adds. “If you are a public employee, they can get your e-mail records. They can get anyone’s phone records. People these days leave electronic trails.”

As a result, she says, potential whistleblowers will think twice before going to the press. “It’s going to have a chilling effect—sources will be less likely to turn information over to reporters,” she said. “As a result citizens will have less of the information they need about what is going on in our country and who they should vote for.”

There is, it must be noted, a double standard in the handling of leaks of classified information. In Washington, the same senior officials who deplore leaks and warn that they imperil national security regularly hold “backgrounders,” calling in reporters to discuss policies, intelligence information and other sensitive issues with the understanding that the information can be attributed only to “administration officials” or some other similarly vague source. The backgrounder is really a kind of group leak.

Backgrounders have been a Washington institution for years. Even presidents employ them. As the columnist James Reston famously noted, “The ship of state is the only known vessel that leaks from the top.” Lower-level officials who divulge secrets can be jailed, but presidents and other high officials have often included classified material in their memoirs.

Despite this double standard, Congress has recognized that it is often in the public interest for government employees to report wrongdoing and that public servants who do so should be protected from retaliation by their superiors. In 1989, Congress enacted the Whistleblower Protection Act, designed to protect employees who report violations of law, gross mismanagement, waste, abuse of authority or dangers to public health and safety.

Critics say the statute has too often failed to prevent retaliation against whistleblowers. Repeated efforts to pass a stronger law failed this past December when a single senator anonymously placed a “hold” on the bill. The legislation would have covered workers at airports, at nuclear facilities and in law enforcement, including the FBI. Earlier versions of the bill, backed by the Obama administration, would have included employees of intelligence and national security agencies, but House Republicans, apparently worried about leaks on the scale of the WikiLeaks disclosures, cut those provisions.

Meanwhile, whistleblowers may draw solace from reports this past April that the Justice Department had suspended its investigation of Thomas Tamm, a former department lawyer. Tamm has said he was a source for the 2005 New York Times story disclosing the existence of the warrantless wiretapping program. After a probe lasting five years, that leak case was effectively closed. But that decision did not close the case of U.S.A. v. Thomas Andrews Drake.

David Wise has written several books on national security. The latest is Tiger Trap: America’s Secret Spy War with China.