Looking at the Battle of Gettysburg Through Robert E. Lee’s Eyes

Anne Kelly Knowles, the winner of Smithsonian American Ingenuity Awards, uses GIS technology to change our view of history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ingenuity-Awards-Anne-Kelly-Knowles-631.jpg)

Anne Kelly Knowles loves places where history happened. She traces this passion to family trips she took as a girl in the 1960s, when her father would pile his wife and four children into a rented RV for odysseys from their home in Kalamazoo, Michigan, to iconic sites from America’s past.

“We’d study the road atlas and plot trips around places like the Little Bighorn and Mount Rushmore,” Knowles recalls. “Historical landmarks were our pins in the map.” Between scheduled stops, she and her father would leap out of the RV to take pictures of historical markers. “I was the only one of the kids who was really jazzed about history. It was my strongest connection with my dad.”

Decades later, Knowles’ childhood journeys have translated into a pathbreaking career in historical geography. Using innovative cartographic tools, she has cast fresh light on hoary historical debates—What was Robert E. Lee thinking at Gettysburg?—and navigated new and difficult terrain, such as mapping the mass shootings of Jews in Eastern Europe by Nazi death squads during World War II.

Knowles’ research, and her strong advocacy of new geographic approaches, have also helped revitalize a discipline that declined in the late 20th century as many leading universities closed their geography departments. “She’s a pioneer,” says Edward Muller, a histor- ical geographer at the University of Pittsburgh. “There’s an ingenuity in the way she uses spatial imagination to see things and ask questions that others haven’t.” Adds Peter Bol, a historian at Harvard and director of its Center for Geographic Analysis: “Anne thinks not just about new technology but how mapping can be applied across disciplines, to all aspects of human society.”

My own introduction to Knowles’ work occurred in August, when Smithsonian asked me to profile a recipient of the magazine’s award for ingenuity. Since the prizewinners weren’t yet public, I was initially told nothing other than the recipient’s field. This made me apprehensive. My formal education in geography ended with fifth-grade social studies class, during which a teacher traced the path of the Amazon on a Mercator projection map that made Greenland loom larger than South America. I knew, vaguely, that new technology had transformed this once-musty discipline, and I expected the innovator I’d been asked to profile would be a NASA scientist or an engineering nerd closeted in a climate-controlled computer lab in Silicon Valley.

No part of this proved true, beginning with the setting. Knowles, 55, is a professor at Middlebury College, which is close to the Platonic ideal of a New England campus. Its rolling lawns and handsome buildings, mostly hewn from Vermont marble, perch on a rise with sweeping views of the Green Mountains and Adirondacks. Knowles fits her liberal arts surrounds, despite belonging to a specialty she calls “fairly macho and geeky.” A trim woman with short hair and cornflower-blue eyes, she wears a white tunic, loose linen trousers and clogs, and seems very at home amid the Yankee/organic quaintness of Middlebury.

But the biggest surprise, for me, was Knowles’ book-lined office in the geography department. Where I’d imagined her crunching data before a vast bank of blinking screens, I instead found her tapping at a humble Dell laptop.

“The technology is just a tool, and what really matters is how you use it,” she says. “Historical geography means putting place at the center of history. No supercomputers are required.” When I asked about her math and computing skills, she replied: “I add, subtract, multiply, divide.”

Her principal tool is geographic information systems, or GIS, a name for computer programs that incorporate such data as satellite imagery, paper maps and statistics. Knowles makes GIS sound simple: “It’s a computer software that allows you to map and analyze any information that has a location attached.” But watching her navigate GIS and other applications, it quickly becomes obvious that this isn’t your father’s geography.

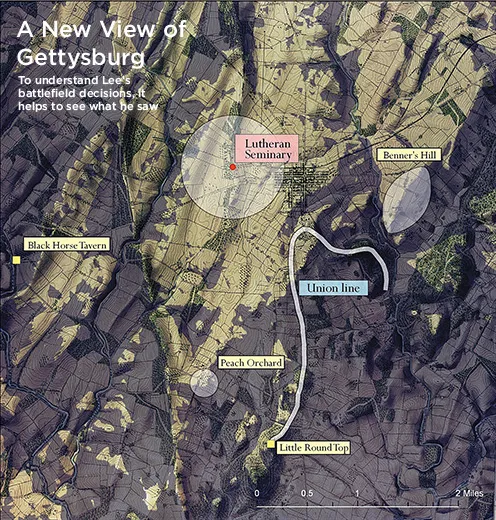

First, a modern topographical map of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, appears on her screen. “Not enough detail,” she says, going next to a contour map of the same landscape made in 1874, which she has traced and scanned. “Here’s where the carto-geek in me comes out,” she says, running her finger lovingly across the map and noting how it distinguishes between hardwood forest, pine woods and orchards—the kind of fine-grained detail that is crucial to her work.

Then, deploying software used in the defense industry, she taps functions such as “triangulated irregular network” and “viewshed analysis” and something that “determines the raster surface locations visible to a set of observer features.” I’m simplifying here. Imagine pixels and grids swimming across the screen in response to keystroke commands that are about as easy to follow as the badly translated instructions that came with your last electronic device. “There’s a steep learning curve to GIS,” Knowles acknowledges.

What emerges, in the end, is a “map” that’s not just color-coded and crammed with data, but dynamic rather than static—a layered re-creation that Knowles likens to looking at the past through 3-D glasses. The image shifts, changing with a few keystrokes to answer the questions Knowles asks. In this instance, she wants to know what commanders could see of the battlefield on the second day at Gettysburg. A red dot denotes General Lee’s vantage point from the top of the Lutheran Seminary. His field of vision shows as clear ground, with blind spots shaded in deep indigo. Knowles has even factored in the extra inches of sightline afforded by Lee’s boots. “We can’t account for the haze and smoke of battle in GIS, though in theory you could with gaming software,” she says.

Scholars have long debated Lee’s decision to press a frontal assault at Gettysburg. How could such an exceptional commander, expert in reading terrain, fail to recognize the attack would be a disaster? The traditional explanation, favored in particular by Lee admirers, is that his underling, Gen. James Longstreet, failed to properly execute Lee’s orders and marched his men sideways while Union forces massed to repel a major Confederate assault. “Lee’s wondering, ‘Where is Longstreet and why is he dithering?’” Knowles says.

Her careful translation of contours into a digital representation of the battlefield gives new context to both men’s behavior. The sight lines show Lee couldn’t see what Longstreet was doing. Nor did he have a clear view of Union maneuvers. Longstreet, meanwhile, saw what Lee couldn’t: Union troops massed in clear sight of open terrain he’d been ordered to march across.

Rather than expose his men, Long- street led them on a much longer but more shielded march before launching the planned assault. By the time he did, late on July 2, Union officers—who, as Knowles’ mapping shows, had a much better view of the field from elevated ground—had positioned their troops to fend off the Confederate advance.

Knowles feels this research helps vindicate the long-reviled Longstreet and demonstrates the difficulties Lee faced in overseeing the battle. But she adds that her Gettysburg work “raises questions rather than providing definitive answers.” For instance: Lee, despite his blind spots, was able to witness the bloody repulse of Longstreet’s men that afternoon. “What was the psychological effect on Lee of seeing all that carnage? He’s been cool in command before, but he seems a bit unhinged on the night of the second day of battle, and the next day he orders Pickett’s Charge. Mapping what he could see helps us ask questions that haven’t been asked much before.”

Knowles says her work has been well received by Civil War scholars. But that’s partly because military historians are more open than others to new geographical techniques. Many historians lack the technical know-how and assistance to master systems like GIS, and are accustomed to emphasizing written rather than visual sources.

“The old school, in history and geography, dug up records and maps, but did not pay much attention to the spatial aspect of history,” says Guntram Herb, a colleague of Knowles’ in Middlebury’s geography department. “And there’s this lingering image of geography as boring and pointless—what’s the capital of Burkina Faso, that sort of thing.”

Knowles’ work has helped reshape this outdated image. To students who now arrive at college with computer savvy and familiarity with Google Earth and GPS, geography seems cool and relevant in a way it didn’t in my long-ago social studies class. Knowles has also brought GIS, once a fringe methodology mainly used by planners to plot transportation routes and land-use surveys, into the historical mainstream. And she’s done so by creating teams of scholars from different areas of expertise, which is common in the sciences but less so among historians. “Technical expertise, archival expertise, geographic imagination—no one has it all,” Knowles says. “You have to work together.”

This embrace of collaboration, and willingness to cross academic boundaries, stems from the unusual path Knowles has followed since her girlhood in Kalamazoo. If she were to map her own career, it would show loops and islands rather than a linear progression. At first, her love of family journeys through the American past didn’t translate into an academic interest in history. “I wrote poetry and loved literature,” she says. As an English major at Duke, she started a magazine and was also a talented modern dancer, which led her to New York City after college.

There, she did editing work and after marrying and moving to Chicago, she worked for textbook publishers. One of her assignments was developing a text that told U.S. history through maps. The consulting editor was a University of Chicago geographer who conceived and compiled 110 maps and took Knowles on field trips. “I was blown away,” she says. “Mapping history brought everything to ground and showed me how history resides in the landscape.”

This led her to graduate study in geography at the University of Wisconsin, a teaching stint in Wales, a postdoctorate at Wellesley College, and a lonely period when she couldn’t find a job and formed her own community of like-minded scholars, devoted to the historical application of GIS. This was also the period when she conceived her breakthrough study of Gettysburg. “I was unemployed, down in the dumps, and was brushing my teeth one morning when I thought, what could Lee see, actually? I knew there was a GIS method, used to site ski runs and real estate views, and wondered what would happen if I applied that to Gettysburg.”

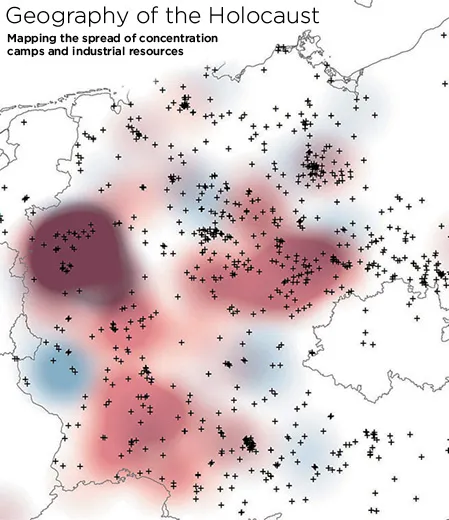

Though she’s now been ensconced at Middlebury for a decade, Knowles continues to push boundaries. Her current project is mapping the Holocaust, in collaboration with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and a team of international scholars. Previously, most maps of the Holocaust simply located sites such as death camps and ghettos. Knowles and her colleagues have used GIS to create a “geography of oppression,” including maps of the growth of concentration camps and the movement of Nazi death squads that accompanied the German Army into the Soviet Union.

The first volume of this work is going to press next year, and in it, Knowles and her co-writers acknowledge the difficulty of using “quantitative techniques to study human suffering.” Their work also raises uncomfortable questions about guilt and complicity. For instance, her colleagues’ research shows that Italians may have been more active in the arrest of Jews than commonly acknowledged, and that Budapest Jews, wearing yellow arm-bands, walked streets occupied by non-Jewish businesses and citizens rather than being sequestered out of sight.

Knowles hopes the ongoing work will contribute not only to an understanding of the Holocaust, but also to the prevention of genocide. “Mapping in this way helps you see patterns and predict what may happen,” she says.

More broadly, she believes new mapping techniques can balance the paper trail that historians have traditionally relied on. “One of the most exciting and important parts of historical geography is revealing the dangers of human memory.” By injecting data from maps, she hopes historical geography will act as a corrective and impart lessons that may resonate outside the academy. “We can learn to become more modest about our judgments, about what we know or think we know and how we judge current circumstances.”

Knowles is careful to avoid over-hyping GIS, which she regards as an exploratory methodology. She also recognizes the risk that it can produce “mere eye candy,” providing great visuals without deepening our understanding of the past. Another problem is the difficulty of translating complex maps and tables into meaningful words and stories. GIS-based studies can, at times, be about as riveting to read as reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Aware of these pitfalls, Knowles is about to publish a book that uses GIS in the service of an overarching historical narrative. Mastering Iron, due out in January, follows the American iron industry from 1800 to 1868. Though the subject matter may not sound as grabby as the Holocaust or Gettysburg, Knowles has blended geographical analysis with more traditional sources to challenge conventional wisdom about the development of American industry.

Like so much of Knowles’ work, the book sprang from her curiosity about place and past—an almost mystical connection she feels to historic ground. Years ago, while researching Welsh immigrants in Ohio, she visited the remains of an early 19th-century blast furnace. “It was draped in vines and seemed like a majestic ruin in the Yucatán. Something mighty and important, full of meaning and mystery. I wondered, how was that machine made and used, how did it work, how did people feel about it?”

Finding answers took years. Working with local histories, old maps and a dense 1859 survey called The Iron Manufacturer’s Guide (“one of the most boring books on earth,” Knowles says), she painstakingly created a database of every ironworks she could locate, from village forges to Pittsburgh rolling mills. She also mapped factors such as distances from canals, rail lines, and deposits of coal and iron ore. The patterns and individual stories that emerged ran counter to earlier, much sketchier work on the subject.

Most previous interpretations of the iron industry cast it as relatively uniform and primitive, important mainly as a precursor to steel. Knowles found instead that ironworks were tremendously complex and varied, depending on local geology and geography. Nor was the industry simply a steppingstone to steel. The manufacture of iron was “its own event,” vital to railroads, textile factories and other enterprises; hence, a driving force in the nation’s industrial revolution.

Knowles also brings this potentially dry subject alive with vivid evocations of place (Pittsburgh, according to a journalist she quotes, looked like “hell with the lid taken off”) and the words and stories of individuals who made and sold iron. The industry required extremely skilled laborers who “worked from sight and feel” at harsh jobs like puddling, which meant stirring “a mass of white-hot iron at close range to rid it of impurities.” At the other end were entrepreneurs who took remarkable risks. Many failed, including magnates who had succeeded in other industries.

To Knowles, this history is instructive, even though the story she tells ended a century and a half ago. “There are analogues to today, entrepreneurs overreaching their expertise and going into businesses they don’t understand.” As always, she also stresses the specificity of place. “In trying to export American capitalism, we fail to appreciate local circumstances that help businesses to succeed or fail. We shouldn’t assume we have a good model that can simply be exported.”

Though Knowles’ research has centered on gritty industry, genocide and the carnage at Gettysburg, she retreats at day’s end through rolling farmland to her home eight miles from Middlebury. En route, she instinctively reads the landscape, noting: “The forest cover would have been much less a hundred years ago, it was all cleared then. You can see that in how scrubby the trees are, they’re second and third growth.”

Her old farmhouse has wide pine floorboards and a barn and apple trees in the yard. She does most of her writing in a room with a view of an abandoned one-room schoolhouse. This faded rural setting is a striking contrast to the global and digital universe that Knowles inhabits in her research. But to her there’s no disconnect. One constant in her life is the keen sense of place she’s had since childhood. “Where we are on the map matters,” she says. “So does mental space. We all need that, and I find it here.”