Madame Restell: The Abortionist of Fifth Avenue

Without benefit of medical training, Madame Restell spent 40 years as a “female physician”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121127102112restell1smaller2-web.jpg)

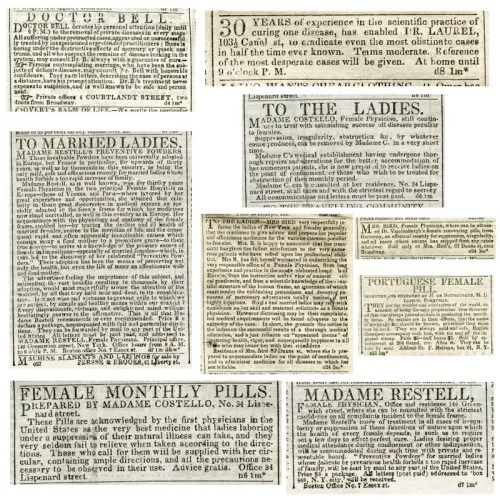

Victorian-era women experiencing “female trouble” could pick up a daily newspaper, scan the advertisements and translate the euphemisms. A dash of “uterine tonic,” an application of a “female wash,” a brushing of “carbolic purifying powder” or any product with “French” in the title promised to prevent conception, while a “female regulator,” “rose injections” or a dose of “cathartic pills” could alleviate “private difficulties” and “remove obstructions.” They knew the key ingredients—pennyroyal, savin, black draught, tansy tea, oil of cedar, ergot of rye, mallow, motherwort—as well as the most trusted name in the business: Ann Lohman, alias Madame Restell, whose 40-year career as a “female physician” made her a hero to desperate patients and “the Wickedest Woman in New York” to nearly everyone else.

Restell, like many self-proclaimed physicians of the time, had no real medical background. Born Ann Trow in May 1812 in Painswick, England, she had little formal education and began working as a maid at age 15. A year later she married a tailor named Henry Summers. They had a daughter, Caroline, in 1830, and the following year sailed for New York City, where they settled on William Street in Lower Manhattan. A few months after they arrived, in August 1831, Henry died of bilious fever. Ann supported herself as a seamstress, doing piecework at home so she could look after Caroline while she worked, all the while longing for something better. Around 1836, she met 27-year-old Charles Lohman, a printer at the New York Herald. He was well-educated and literate, a habitué of a bookstore on Chatham Street where the city’s radical philosophers and freethinkers gathered to debate, and he began publishing tracts about contraception and population control.

It’s unclear how Ann first embarked upon the patent-medicine business, but Charles encouraged her fledgling career. Together they concocted a story of a trip to Europe where Ann allegedly trained as a midwife with her grandmother, a renowned French physician named Restell. Upon her return, she assumed the moniker “Mrs. Restell” (soon tweaking it to “Madame Restell”), and Charles encouraged her to advertise in the newspapers. Her first notice ran in the New York Sun of March 18, 1839, and read, in part:

TO MARRIED WOMEN.—Is it not but too well known that the families of the married often increase beyond what the happiness of those who give them birth would dictate?… Is it moral for parents to increase their families, regardless of consequences to themselves, or the well being of their offspring, when a simple, easy, healthy, and certain remedy is within our control? The advertiser, feeling the importance of this subject, and estimating the vast benefit resulting to thousands by the adoption of means prescribed by her, has opened an office, where married females can obtain the desired information.

Clients arrived at her Greenwich Street office from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., and if they couldn’t seek treatment in person, Restell responded by mail, sending Preventative Powder at $5 per package or Female Monthly Pills, $1 apiece. Her pills (as well as those of her competitors) simply commercialized traditional folk remedies that had been around for centuries, and were occasionally effective. Restell counted on clients returning for surgical abortions if the abortifacients failed—$20 for poor women, $100 for the rich.

As her practice flourished it attracted other aspiring “female physicians,” male and female, and Restell began warning prospective clients to “beware of imitators.” To remain competitive she began expanding her range of services. In addition to selling abortifacients, she opened a boardinghouse where clients with unwanted pregnancies could give birth in anonymity. For an additional fee, she facilitated the adoption of infants. Restell placed more newspaper ads, many referring to the thousands of letters she’d received from grateful customers.

When Madame Restell began her practice, New York State law regarding abortion reflected contemporary folk wisdom, which held that a fetus wasn’t technically alive until “quickening”—the moment when the mother felt it first move inside the womb, usually around the fourth month. An abortion before quickening was legal, but an abortion after quickening was considered to be second-degree manslaughter. Restell tried to determine how far along a patient was in her pregnancy before offering her services; if she intervened too late, she risked a $100 fine and one year in prison.

She had her first major brush with the law in 1840, when a 21-year-old woman named Maria Purdy lay on her deathbed, suffering from tuberculosis. She told her husband she wished to make a confession: While pregnant the previous year, she decided she didn’t want to give birth again; they had a ten-month-old child and she couldn’t handle another so soon. She had visited Restell’s office on Greenwich Street and joined several women waiting in the front parlor. When her turn came, Restell listened to her story and gave her a small vial of yellow medicine in exchange for a dollar.

Purdy took one dose that night and two the next day but then stopped, suddenly worried about the potential consequences. A doctor analyzed the medicine and concluded it contained oil of tansy and spirits of turpentine and advised her to never take it again. She returned to Restell, who told her that for $20 an operation could be performed without pain or inconvenience. Purdy had no cash, and instead offered a pawn ticket for a gold watch chain and a stack of rings, which Restell accepted. She led Purdy behind a curtain to a darkened room, where a strange man—not Restell’s husband—placed his hands on her abdomen and declared she was only three months along (if Purdy was past the first trimester, she didn’t correct him). She had the surgery, and was convinced that her present illness was a result. After hearing her deathbed confession her husband went to the police, who arrested Restell and charged her with “administering to Purdy certain noxious medicine… … procuring her a miscarriage by the use of instruments, the same not being necessary to preserve her life.”

The case launched a debate that played out in the press, and the debate was as charged as it is today. One antiabortion advocate called Restell “the monster in human shape” responsible for “one of the most hellish acts ever perpetrated in a Christian land.” She was a threat to the institution of marriage, allowing women to “commit as many adulteries as there are hours in the year without the possibility of detection.” She encouraged prostitution by removing the consequences. She allowed wives to shirk the duties of motherhood. She insulted poor women by providing abortions when they could seek aid and solace from their church. She not only abetted immoral behavior but also harmed misguided and naïve women, acting as a “hag of misery” preying upon human weakness. The word “Restellism” became synonymous with abortion.

Restell decided to defend herself, placing an ad in the New York Herald in which she offered $100 to anyone who could prove that her medicine was harmful. “I cannot conceive,” she wrote, “how men who are husbands, brothers, or fathers can give utterance to an idea so intrinsically base and infamous, that their wives, their sisters or their daughters, want but the opportunity and ‘facility’ to be vicious, and if they are not so, it is not from an innate principle of virtue, but from fear. What is female virtue, then, a mere thing of circumstance and occasion?”

She was found guilty at trial, but the case was appealed on the ground that Maria Purdy’s deathbed statement was not admissible. The appellate court ruled that such depositions were admissible only in civil suits. Restell was retried, with Purdy’s statement removed from the evidence, and found not guilty. Emboldened, Restell opened branch offices in Boston and Philadelphia and increased her advertising, targeting “married ladies whose delicate or precarious health forbids a too rapid increase of family.”

In 1845, the New York State legislature passed a bill stipulating that providing abortions or abortifacients at any stage of pregnancy was a misdemeanor punishable by a mandatory year in prison. Women who sought abortions or attempted to self-abort would also be liable, subject to a $1,000 fine, a prison sentence of tree to 12 months, or both. The legislators apparently overlooked the possibility that this provision would discourage testimony from women who had undergone abortions, making it more difficult to prosecute abortionists.

Public scrutiny of Restell continued unabated—she was accused in the press, on the basis of an anonymous letters, of performing a fatal abortion on Mary Rogers, the real-life inspiration for the title character in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Mystery of Marie Roget”—but she managed to avoid legal trouble for two years. In the fall of 1847, a woman named Maria Bodine visited her clinic, having been referred by an anonymous “sponsor.” Restell decided she was too far along for an abortion and suggested the woman stay and board instead, but Bodine’s lover insisted. Restell refused several times before allowing the surgery. Afterward, in pain, Bodine consulted a physician, who suspected an abortion and reported her to the police. She turned state’s evidence, and Restell was arrested for second-degree manslaughter.

Restell was found guilty of misdemeanor procurement and sentenced to a year on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). Upon her release she claimed she would no longer offer surgical abortions, but would still provide pills and stays in her boardinghouse. In an attempt to improve her image she applied for United States citizenship—one had to be a “person of good character” to be approved—and was naturalized in 1854. The mayor of New York, Jacob A. Westervelt, officiated at her daughter’s wedding.

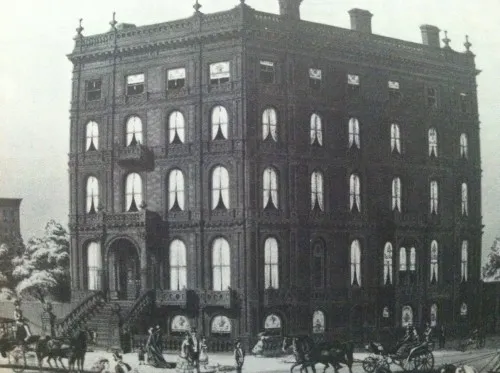

But Restell wasn’t able to escape her reputation. Newspaper reports seemed as bothered by her wealth as by how she obtained it, detailing her collection of diamonds and pearls, her furs, her ostentatious carriage with four horses and a liveried coachman, her brownstone mansion on the corner of 52nd Street and 5th Avenue (built in part, it was said, to annoy the first Roman Catholic archbishop of New York, John Hughes, who had denounced her from his pulpit and who had bought the next block on which to build St. Patrick’s Cathedral). She was now so infamous nationwide that she was included in several guidebooks to the city, one of which dubbed her “the Wickedest Woman in New York.”

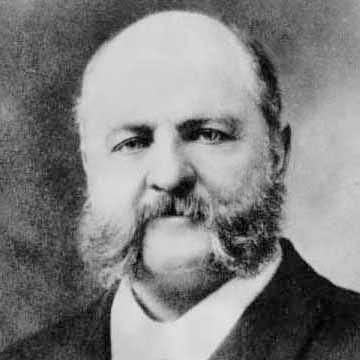

Anthony Comstock, the founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, likened pornography to cancer and drew no distinction between birth control and abortion. A federal passed in March 1873, which became known as the Comstock Law, made it a misdemeanor to sell or advertise obscene matter by mail, and made specific reference to “any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion.” Telling someone where they could find such information carried a prison sentence of six months to five years and a fine of up to $2,000.

Comstock embarked on a personal campaign to hunt down violators. In 1878 he rang the bell of Madame Restell’s basement office on East 52nd Street, claiming to be a married man whose wife had already given him too many children. He was worried about her health and hoped Restell might be able to help, he said. She sold him some pills. Comstock returned the following day with a police officer and had her arrested. During a search he found pamphlets about birth control and some “instruments,” along with instructions for their use.

Once again Restell defended herself in the press. “He’s in this nasty detective business,” she said of Comstock. “There are a number of little doctors who are in the same business behind him. They think if they can get me in trouble and out of the way, they can make a fortune. If the public are determined to push this matter, they will have a good laugh when they learn the nature of the terrible items of the preventative prescriptions. Of course, if there’s a trial it will all come out.”

This time there was no trial. On April 1, 1878, Restell’s chambermaid found her nude body half-submerged in the bathtub, her throat slit from ear to ear. House servants told reporters that Restell had been restless and despondent, pacing her home and crying, “Why do they persecute me so? I have done nothing to harm anyone.” Since it was April Fool’s Day, Comstock initially believed the report to be a tasteless joke. When he realized it was true, he reached for his file on Ann Lohman and penned a final comment: “A bloody ending to a bloody life.”

Sources:

Books: Clifford Browder, The Wickedest Woman in New York. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1988; A. Cheree Carlson, The Crimes of Womanhood. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009; Louis J. Palmer, Encyclopedia of Abortion in the United States. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002; Janet Farrell Brodie, Contraception and Abortion in 19th Century America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994; Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and the Law in the United States, 1867-1973. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1997.

Articles: “End of an Infamous Life.” New York Herald Tribune, April 2, 1878; “A Vile Business Stopped.” New York Herald Tribune, February 12, 1878; “Madame Restell and Her Furnace for Destroying Babies.” Washington (PA) Review and Examiner, January 16, 1867; “Madame Restell Repudiated.” Newport Mercury, March 24, 1855; “Case of Madam Restell.” Boston Evening Transcript, February 9, 1848; “Another Death by Female Physicians and Arrest of Madame Restell.” Boston Courier, April 18, 1844; “The Wickedest Woman in New York.” Helena (MT) Weekly, November 26, 1868.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)