Making the Rounds With Santa Claus Smith

For six years, an elderly tramp toured the U.S., paying those who helped him with checks for sums of up to $900,000

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111205115021santa-claus-smith-web.jpg)

On the evening of July 18, 1935, in an America still crushed in the coils of the Great Depression, an old man with a long white beard appeared on the front lawn of a farm off Route 1 in Metamora, Indiana.

It was late, nearly dusk, and when the farmer’s wife came out to ask what the man wanted, he begged her for a piece of bread. “He had a very kind face,” she wrote some days later,

and it has always been my custom to give to tramps if I have anything I can handy give. He was carrying a pack on his back so I told him to set it down on the lawn. I had a nice warm supper cooked so I served him on the lawn. He seemed to be very hungry. I gave him a second serving. When he finished he took from his pack two checks copied from brown paper, looked like they were cut from paper bags. He came forward and handed these to me with his plate.

According to this woman, “his face was so kind it is hard to believe he meant anything false.” But when she looked down at the paper checks, she saw that one had been written for $25,000, and the other for $1,000.

More than a year later, on October 23, 1936, the same old man wandered into a lunchroom on a highway outside Columbus, Texas. He told the waitress he had no money but asked her for a cup of coffee. Feeling sorry for him, she took him into the kitchen and fed him a bowl of stew and a jelly roll with his coffee. The old man ate his fill and, while the waitress was serving other customers, took another piece of paper from his pack, scribbled on it in indelible pencil, and slipped it beneath his coffee cup before taking up his pack and hurrying off into the night. The waitress returned to find that the slip of paper was a blank check for $27,000, written on the Irving National Bank of New York and signed “John S. Smith of Riga, Latvia, Europe.” On the back he had scribbled the words: “Fill your name in, send to bank.”

Four days after that, John S. Smith was in Yuma, Arizona, where he left a check for $2,000 in exchange for a cup of coffee. Early in November, in Indianola, Mississippi, he handed another farmer’s wife two checks totaling $26,000. And in December, in Fort Worth, a young woman sitting in a parked car was approached by an elderly, bearded man who begged her for a nickel. She gave him a dime, prompting him to use her fender as a desk and write a check for $950. When the girl laughed and thanked him, he took the check back, tore it up, and wrote out another one for $26,000.”That’s for your sweet smile,” he said.

In all, between 1934 and 1940, the mysterious John S. Smith traveled as far north as Clinton, Connecticut, and as far west as Los Angeles, scattering pencil-and-paper checks written on the Irving National for sums totaling several million dollars. He paid as little as $90 for what a minister’s wife in Terre Haute, Indiana, insisted was “a good, hot lunch,” and as much as $600,000 for a hamburger cooked for him by a waitress in New Iberia, Louisiana. He paid more for food than he did for the rides he sometimes hitched, and more to women than to men. He also showed an affinity for cats, leaving checks totaling $5,000 to a woman in South Dakota to pay for “upkeep the black and white cat name Smiles.” All his checks were written on brown paper, often spotted with grease, and they shared several other distinctive characteristics: handwriting in a vaguely gothic style, the misspelling of “thousand” as “tousand” and the crude symbol of a smiley face, with pencil dots for eyes and nose.

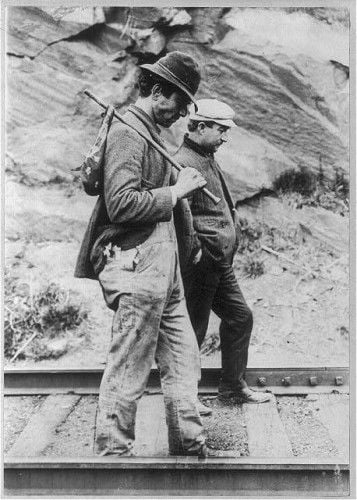

Eccentric though he clearly was, John S. Smith was only one of the hundreds of thousands of men who took to the roads and rails of the United States between the coming of railways and the 1930s, an era when—for all its harshness and its frequent tragedy—the traveling life was regarded by many romantic young men as the ultimate test of manhood. Some traveled because they had to, because they were craftsmen who had grown up in towns too small to make full-time use of their services. Others were itinerants who met the need for seasonal labor on farms. And a smaller, but far from insignificant, number drifted because it suited them. “To those who idealized them, hoboes and tramps were the last of the rugged individualists,” the writer Richard Wormser notes. “But the reality of the hobo world was often far different. It was a life in which a man might go days without food, weeks without a decent place to sleep, and months without clothing…. Jack London, who chose tramp life as a teenager, saw it for what it was: ‘I was in the pit, the abyss, the human cesspool, the schools and charnel house of our civilization. This is the part that society chooses to ignore.’ ”

What drove John S. Smith onto the roads is harder to know. He confided to a woman in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, that he had left home in 1934 because the Depression had “got on his mind”; she suspected, rather, that he had “got loose from an institution and has been lost ever since.” The most romantic depiction of the tramp can be found in a letter written by a young woman from San Antonio, who received a check for $6,000 from him. “He stated that he purposely wore ragged clothes and rewarded those who helped him,” she recorded.

That letter, and others like it, found its way into the files of the Irving Trust—a New York institution based at 1 Wall Street, the successor of the defunct Irving National Bank and the unwilling recipient for reams of correspondence that flowed in from people who encountered John S. Smith. Most of the letters were accompanied by Smith’s grease-stained slips of rough brown paper. They inquired whether the checks could be cashed, and adopted a variety of tones: some suspicious, some disbelieving, not a few filled with hope. “I received these checks from an old gentleman who ate breakfast at our home,” a Texas farmer wrote in December 1937. “I asked the bank here to handle same for me, and they seemed to think they were no good. This man had no reason to give us these checks knowing they were no good. So I still believe he wanted us to have this amount of money and we sure need it. Wishing you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.”

According to the great New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell, who was given access to the tramp’s odd file in 1940 in exchange for his promise not to name any of the hopeful letter-writers, the clerks at the Irving Trust devoted considerable effort to solving the many mysteries John S. Smith created. First they puzzled over the problem that the Irving National Bank had gone out of existence in 1923, 11 years before the first checks drawn on it were written; did this mean the old tramp had long ago kept an account there? They searched their records, together with those of the old Irving National, for any that might have belonged to a man who had been born in Riga, Latvia, Europe. None could be found under any name at any date. Next, believing that Smith might once have worked in their building as a janitor or guard, they scoured their employment rolls. Again, they found no trace of any John S. Smith.

In the end, Mitchell noted, the Trust officials concluded that Smith was “a simple-minded, goodhearted old man who feels that he should reward those treating him with kindness.” They made no attempt to trace him or have him arrested, since there was no evidence of forgery or fraud, and he seemed never to attempt to cash a check or actually buy anything with one. “The bank people call him Santa Claus Smith and wish that he had millions of dollars on deposit,” Mitchell added, and he noted that, from time to time, a bank official would pull the Smith file and amuse himself by tracing the tramp’s peregrinations on a map.

For a short time, it seemed the mystery might be solved. A letter written by John S. Smith, postmarked Wabash, Indiana, and (Mitchell observed) “scribbled wildly on the back of seven lunchroom menus” was delivered to the bank. Sadly, while it began, “Irv. Nat. Bank of N.Y. Dear Sir,” it then became illegible. The letter had apparently been kept in the tramp’s pockets for a while and become stained with grease and tobacco crumbs. After that it appeared to have been dipped in water, reducing Smith’s scribbles to nothing more than purple blots. Still, one of the bank officials fetched a magnifying glass, and—”after a considerable amount of agonizing labor,” Mitchell wrote—made out a handful of phrases. These were: “listen those three waitress,” “put something in that bank,” “in USA for 26yrs 30yrs 22,” “mortgage and now,” “to see about cats,” “waitress girl in that place in Ohio,” and “all over USA.”

Attached to the letter were two of Smith’s checks. One was for $15,000 and the other for $6,000. Both were written on the Irving National Bank, and both were made payable to the Irving National Bank. Somehow, it seemed a fitting end to the tale of one old tramp’s perpetual circuit of the country.

Sources

Joseph Mitchell. Up in the Old Hotel. New York: Vintage Books, 1993; Mark West. Hoboes: Bindlestiffs, Fruit Tramps, and the Harvesting of the West. New York: Hill and Wang, 2011; Richard Wormser. Hoboes: Wandering in America, 1870-1940. New York: Walker & Co., 1994.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)