Minter’s Ring: The Story of One World War II POW

When excavators in Inchon, Korea discovered a U.S. naval officer’s ring, they had no knowledge of the pain associated with its former owner, Minter Dial

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/POW-Ring-631.jpg)

In the spring of 1962, the United States Navy was excavating a site in Inchon, Korea, when the discovery of human remains led officers to believe they had come across the site of a prisoner-of-war camp. More than a decade earlier, during the Korean War, General Douglas MacArthur commanded some 75,000 United Nations ground forces and more than 250 ships into the Battle of Inchon—a surprise assault that led, just two weeks later, to the recapture of Seoul from the North Korean People’s Army. But the 1962 Inchon excavation led to an unexpected find.

Yi So-young, a Korean laborer at the site, noticed that one of his fellow workers had discovered a gold ring buried in the mud. Yi took a good long look, then turned his back as the worker pocketed the ring, disobeying site rules. Under his breath, the worker said he was going to pawn it at the end of the day.

But Yi was also a driver for U.S. Navy officers, and that afternoon, he found himself chauffeuring Rear Admiral George Pressey, commander of the U.S. Naval forces in Korea. Yi was struck by the resemblance of the ring found at the site to the Annapolis class ring on Pressey’s finger. Yi mentioned the morning’s find to the admiral, and Pressey asked where the ring was.

Suddenly, the vehicle was speeding through the crowded streets of Inchon as the two men visited one pawnshop after another until they found the guilty laborer. The ring was in the process of being smelted. The admiral demanded that it be recovered. It had been partially melted down, but once it cooled and he was able to wipe away the grime, Pressey recognized that it was indeed an Annapolis class ring. Class of 1932. Pressey had been at the U.S. Naval Academy at the same time. His heart began to pound as he tilted the blue stone ring toward the light. Engraved on the inside was a name he knew: Dial.

Nathaniel Minter Dial had been one of Pressey’s best friends at Annapolis. They were teammates on the lacrosse squad, and Pressey and his wife had been members of the wedding party when Dial married his longtime sweetheart, Lisa Porter, in 1934. Pressey had just one thought—to get the ring back to Lisa.

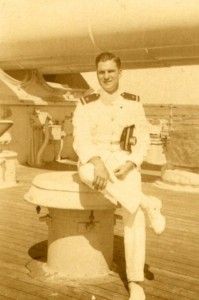

Memories and sadness came flooding over the 51-year-old admiral. Minter Dial, the son of U.S. Senator Nathaniel B. Dial of South Carolina, was the quintessential all-American boy. He was affable, educated, terrifically athletic and married to a beautiful young woman who had given up her theatrical ambitions to start a home and raise a family. He was going places, and in the summer of 1941, he headed for the Pacific.

The last Pressey had heard of his friend was during the Second World War. Both men commanded ships in the Philippines, but Pressey knew Dial had been captured and held at a Japanese camp in northern Luzon. Pressey had even visited the site, years ago. A scrap of paper had been discovered and identified as Dial’s. “Oh God, how hungry…how tired I am,” his friend had scribbled. But that was nearly twenty years before Dial’s ring had been found, and more than a thousand miles from Inchon. Dial had died in captivity near the Philippine city of Olangapo. So what was his ring doing in Korea?

Read more about the sad story of Minter Dial after the jump…

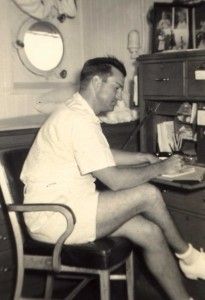

In July of 1941, Minter Dial had taken command of the U.S.S. Napa, a fleet tug used principally to lay down mines and torpedo nets. At first he used his time at sea to develop his typing skills on a portable Underwood, pounding out letters to his wife. But after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor that December, the Napa’s .50.30-caliber Lewis machine guns saw heavy anti-aircraft duty. The Japanese assault on the Philippines that winter overwhelmed American and Filipino forces, trapping more than 75,000 troops on the Bataan peninsula with dwindling supplies and inferior arms. By April of 1942, the self-styled Battling Bastards of Bataan were starving.

The Napa continued to pull duty, running fuel to ships around Manila Bay under heavy fire, until eventually, the fuel ran out. The ship was scuttled off Corregidor Island, and Dial and his crew reported for duty at Corregidor just as Bataan fell to the Japanese. With the Americans trapped on Corregidor, the Japanese shelled them at a rate that made the island one of the most intensely bombed places in the history of warfare. “Try not to worry,” Dial wrote to his wife just days before American and Filipino forces surrendered on May 6, 1942. “Remember that I worship you and always will.” It was the last letter he wrote in freedom.

A week later, Lisa Dial received a cable from the Navy Department saying that her husband was missing and might be a prisoner of war. In a letter to her, Lieutenant Bob Taylor, one of her husband’s good friends, elaborated on the details of the surrender in the Philippines and asked her to “please remember that a prisoner of war has some advantages. He isn’t fighting anymore, and he is fed more than the poor devils on the Corregidor have been getting.” Months would pass before Lisa heard anything else about her husband.

Just before the surrender, Dial had been hospitalized with pneumonia; it was weeks before he was fit enough to be transported to a Japanese POW camp. As fate would have it, he escaped the deadly 60-mile POW transfer known as the Bataan Death March, on which thousands of other American prisoners died of disease and malnutrition. He made the same journey weeks later in the back of a truck, sick with dysentery.

In Feburary of 1943, the Red Cross informed Lisa Dial that her husband was a POW at Cabanatuan Prison Camp, where he would spend the next two and a half years. Surely it was a relief to know that her husband was alive. But she had no way of knowing that Cabanatuan camp would become infamous for disease, malnourishment and torture.

Prisoners went to extraordinary lengths to give hope to people back home. After escaping, Dial’s friend Major Michael Dobervich of the U.S. Marines wrote Lisa Dial that her husband was in “excellent health and spirits” when he last saw him, in October of 1942.

Every few months, the Imperial Japanese Army permitted prisoners to fill out Red Cross cards to inform loved ones of their health, along with fifty-word messages subject to heavy censorship. In one such message to his wife, Dial said he wanted to give his regards to “John B. Body, 356-7 Page St., Garden City, N. Y.” She sent a letter to Mr. Body, but the post office returned it. Several months later, Ruffin Cox, another of Dial’s Annapolis friends, returned from duty and deciphered the message. Recalling that they used to read aloud to each other for cheap entertainment during the Depression, Cox found a copy of John Brown’s Body, by Stephen Vincent Benet—published in Garden City, New York. There, on page 356, were the words of a young Southern prisoner who had been imprisoned in a Union Army camp: “And, woman and children, dry your eyes/The Southern Gentleman never dies./He just lives on by his strength of will,/Like a damn ole rooster too tough to kill.”

As the months passed, the war began to turn against the Japanese. More than two years after he fled the Philippines with the promise, “I came out of Bataan and I shall return,” General Douglas MacArthur indeed returned, and by December of 1944, the Americans had established airstrips on the Philippine island of Mindoro. Luzon was in MacArthur’s sights. That month, Minter Dial’s Red Cross card put his weight at 165 pounds, down from his pre-captivity weight of 200 pounds. Like most of the prisoners at Cabanatuan, he was slowly starving on rations of ten ounces of rice each day. He might easily have used his Annapolis ring to bribe a guard for a few extra helpings of rice, but that would not do. In fact, many of the POW officers hid their Navy and Marine Corps rings (including, at times, in body cavities) to avoid confiscation, and when the men became too weak and feared they might not survive another night, they would pass their valuables on to stronger prisoners, along with messages for their wives.

On December 12, 1944, Dial wrote a letter to his wife—the only letter to reach her after his captivity: “Hug the children close and tell them I adore them. You too must keep brave! And I will. We will be together again—and have a life brimming with happiness. Until then—chin up! You are my life! My love! My all! Yours for always, Minter.”

Dial knew he was about to leave Cabanatuan for another camp, “probably in Japan proper,” and he and the other 1,600 POWs had heard about hazardous and miserable transfers aboard Japanese ships. His December 12 letter included directions on family financial arrangements—a living will, in essence.

On the following morning, Dial and the other prisoners were lined up in the searing heat, staring at the 7,300-ton Oryoku Maru, a passenger ship built around 1930. Japanese soldiers took positions on the top decks, while Japanese civilians (2,000 men, women and children) were placed below deck. The POWs were crammed into three separate holds. Dial and more than eight hundred others were packed into the stern hold, roughly 50 x 70 feet and with ceilings too low for most men to stand up straight. The lack of ventilation and sanitation, together with the rising temperatures within the ship’s metal walls and minimal water rations, led to bouts of severe dehydration. By the following morning, fifty men were dead; their bodies were piled beneath the ship’s driveshaft. And Oryoku Maru had still not departed from Manila Harbor.

The ship set sail at dawn on December 14. That day there was no water for the prisoners—just a small amount of rice. Against international laws, Oryoku Maru was left unmarked as a prisoner ship, and American planes attacked it nine times that day. Bullets ricocheted around the holds as temperatures soared to over 120 degrees. Japanese military personnel were removed from the ship, but the POWs remained locked below. Men were driven to madness on the second night. The “combination of hopelessness, nervous tension and thirst drove us through the most horrible night that a human being could endure,” wrote John Wright, a survivor aboard what became known as the “hell ship.” In the darkness there were screams. Some men committed suicide. Others were murdered. Desperate men drank the blood of warm corpses, or their own urine.

By morning, 50 more prisoners had died before an American torpedo plane scored a direct hit on the ship, instantly killing 200 more. Oryoku Maru caught fire and took on water; surviving prisoners were ordered to abandon ship and swim for shore. Dial began to swim, but he and the other POWs were soon taking fire from both the Japanese guards and oblivious American pilots. He made it to land, but not without injury. Two .50-caliber shells had left gaping wounds in his side and leg. Japanese guards confined the prisoners on a tennis court in the city of Olangapo, and with scant medical help available, he faded fast. Lieutenant Douglas Fisher, one of Dial’s closest friends at Cabanatuan, held him in his arms. Under the torrid Philippine sun, he handed over his Annapolis ring and asked Fisher to give it to his wife. On December 15, 1944, Lieutenant Minter Dial drew his last breath. He was 33 years old.

After five days on the tennis court with no shelter and small rations of rice, Fisher and the other 1,300 or so surviving POWs were boarded on the Enoura Maru and jammed shoulder to shoulder in holds used to transport artillery horses. Ankle-deep in manure, fighting off horse flies and driven mad by thirst, the most desperate prisoners began biting into their own arms so they could suck their blood. The dead were left in the holds for days as the ship sailed for Taiwan, under constant American fire, with one direct hit killing 300 prisoners. Survivors were transferred to the Brazil Maru, which eventually made it to Japan, and, after a total of 47 days, Korea.

From the sweltering heat below decks of the hell ships through the bitter Korean winter, Commander Douglas Fisher managed to survive, clinging to Dial’s ring. He would tie it inside the shreds of clothing his captors provided, or tuck it away beneath a bunk slat at night. When he arrived at a camp in Inchon in February of 1945, his health, too, was failing. Of the 1,620 prisoners taken from the Philippines aboard the Japanese ships, barely 400 would survive the war.

One morning, Fisher awoke in a hospital. The ring was gone. He searched his bunk and the folds of his clothes, but it was nowhere to be found. “I suspected someone had taken it,” he later said.

Fisher survived his ordeal, but was deeply saddened that he failed to honor his friend’s dying wish. After the war, he traveled to Long Beach, California, to meet Lisa Dial and tell her of her husband’s captivity and death. Then, in tears, he apologized for not bringing Minter’s ring with him. Despite Lisa’s expressions of gratitude for his efforts, Fisher was overcome with sorrow; he handed his wristwatch to Minter’s eight-year-old son, Victor, as a token of friendship. Through the freezing and thawing of 18 Korean winters, the ring was buried in the dirt beneath Fisher’s old bunk.

In May of 1962, one month after he discovered the ring in an Inchon pawn shop, Admiral George Pressey arranged for it to be returned to Lisa Dial. Lisa remarried soon after the war in an attempt to bring stability to her family. But she was never able to recover fully from Minter’s death and suffered from depression for the remainder of her life. Stricken with cancer, she died in 1963, at the age of forty-nine.

Victor Dial had the ring mounted in a framed case beside the Navy Cross and the Purple Heart that his father was awarded posthumously. He hung the case at the house where he and his wife were living in the suburbs of Paris, but when they came down for breakfast one morning in 1967, it was missing. Burglars had stolen it from their home while they slept.

Once again, Minter Dial’s ring had vanished.

Sources: Minter Dial II, personal collections; Edward F. Haase, “EF Haase Papers” by Edward F. Haase, United States Navy, a collection of memoirs; Austin C. Schofner, Death March from Bataan. Angus & Robertson, Ltd., Sydney, Australia, 1945; Stephen Vincent Benet, John Brown’s Body. Doubleday, 1928; David Halberstam, The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. Hyperion, 2007; Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific. Quill Press, 1994; Betty B. Jones, The December Ship: A Story of Lt. Col. Arden R. Boellner’s Capture in the Philippines, Imprisonment and Death on a World War II Japanese Hellship. McFarland & Co. Inc. 1992; John M. Wright Jr., Captured on Corregidor: Diary of an American POW in World War II. McFarland Press, 1988. For more information about Lt. Cdr. Minter Dial’s ring: http://www.facebook.com/LtCdrMinterDial

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)