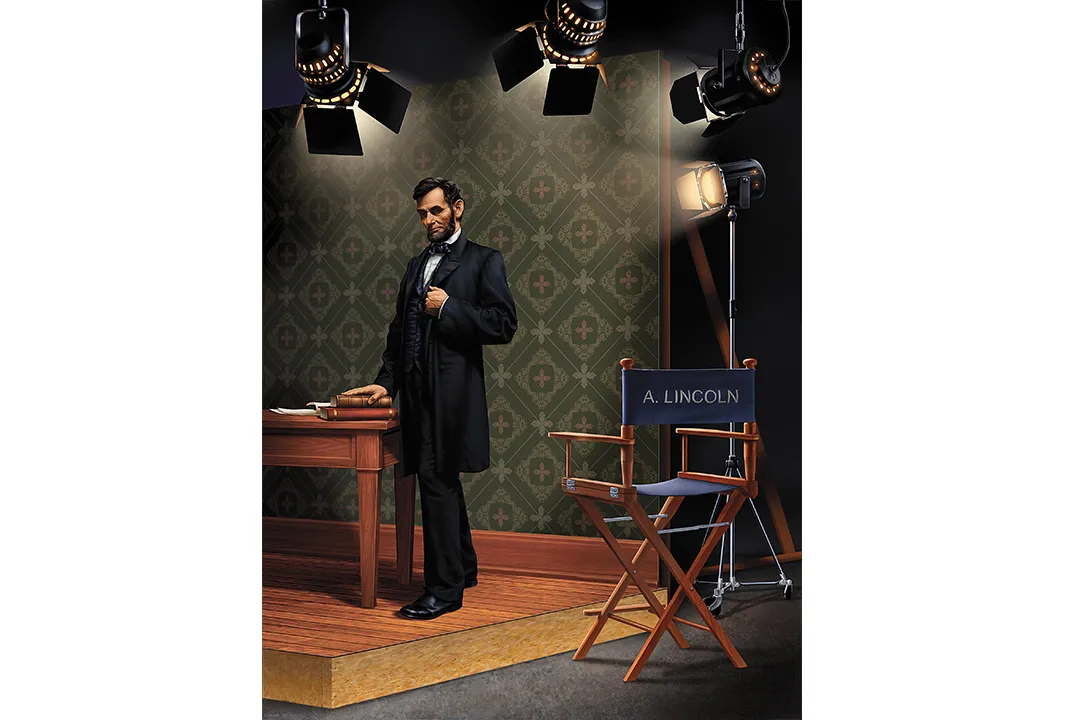

Mr. Lincoln Goes to Hollywood

Steven Spielberg, Doris Kearns Goodwin and Tony Kushner talk about what it takes to wrestle an epic presidency into a feature film

In Lincoln, the Steven Spielberg movie opening this month, President Abraham Lincoln has a talk with U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens that should be studied in civics classes today. The scene goes down easy, thanks to the moviemakers’ art, but the point Lincoln makes is tough.

Stevens, as Tommy Lee Jones plays him, is the meanest man in Congress, but also that body’s fiercest opponent of slavery. Because Lincoln’s primary purpose has been to hold the Union together, and he has been approaching abolition in a roundabout, politic way, Stevens by 1865 has come to regard him as “the capitulating compromiser, the dawdler.”

The congressman wore with aplomb, and wears in the movie, a ridiculous black hairpiece—it’s round, so he doesn’t have to worry about which part goes in front. A contemporary said of Stevens and Lincoln that “no two men, perhaps, so entirely different in character, ever threw off more spontaneous jokes.”

Stevens’ wit, however, was biting. “He could convulse the House,” wrote biographer Fawn M. Brodie, “by saying, ‘I yield to the gentleman for a few feeble remarks.’” Many of his declarations were too funky for the Congressional Globe (predecessor of the Congressional Record), which did, however, preserve this one: “There was a gentleman from the far West sitting next to me, but he went away and the seat seems just as clean as it was before.”

Lincoln’s wit was indirect, friendly—Doris Kearns Goodwin quotes him as describing laughter as “the joyous, universal evergreen of life” in her book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, on which the movie is partly based. But it was also purposeful. Stevens was a man of unmitigated principle. Lincoln got some great things done. What Lincoln, played most convincingly by Daniel Day-Lewis, says to Stevens in the movie, in effect, is this: A compass will point you true north. But it won’t show you the swamps between you and there. If you don’t avoid the swamps, what’s the use of knowing true north?

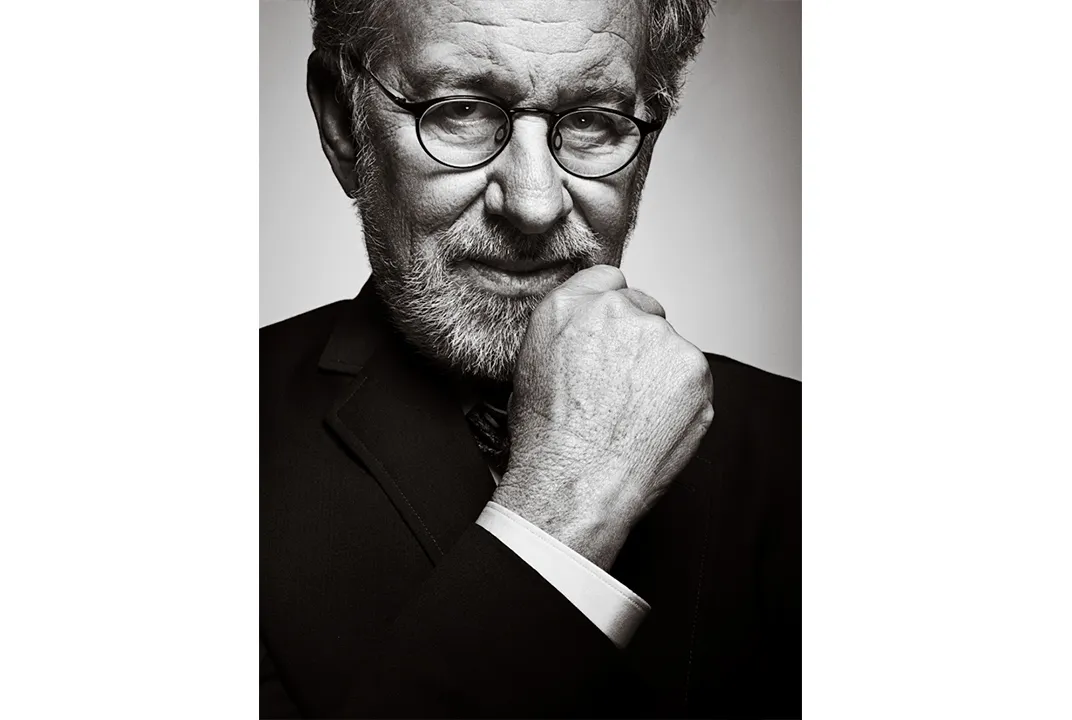

That’s a key moment in the movie. It is also something that I wish more people would take to heart—people I talk with about politics, especially people I agree with. Today, as in 1865, people tend to be sure they are right, and maybe they are—Stevens was, courageously. What people don’t always want to take on board is that people who disagree with them may be just as resolutely sure they are right. That’s one reason the road to progress, or regression, in a democracy is seldom straight, entirely open or, strictly speaking, democratic. If Lincoln’s truth is marching on, it should inspire people to acknowledge that doing right is a tricky proposition. “I did not want to make a movie about a monument,” Spielberg told me. “I wanted the audience to get into the working process of the president.”

Lincoln came out against slavery in a speech in 1854, but in that same speech he declared that denouncing slaveholders wouldn’t convert them. He compared them to drunkards, writes Goodwin:

Though the cause be “naked truth itself, transformed to the heaviest lance, harder than steel” [Lincoln said], the sanctimonious reformer could no more pierce the heart of the drinker or the slaveowner than “penetrate the hard shell of a tortoise with a rye straw. Such is man, and so must he be understood by those who would lead him.” In order to “win a man to your cause,” Lincoln explained, you must first reach his heart, “the great high road to his reason.”

As it happened, the fight for and against slave-owning would take the lowest of roads: four years of insanely wasteful war, which killed (by the most recent reliable estimate) some 750,000 people, almost 2.5 percent of the U.S. population at the time, or the equivalent of 7.5 million people today. But winning the war wasn’t enough to end slavery. Lincoln, the movie, shows how Lincoln went about avoiding swamps and reaching people’s hearts, or anyway their interests, so all the bloodshed would not be in vain.

***

When Goodwin saw the movie, she says, “I felt like I was watching Lincoln!” She speaks with authority, because for eight years, “I awakened with Lincoln every morning and thought about him every night,” while working on Team of Rivals. “I still miss him,” she adds. “He’s the most interesting person I know.”

Goodwin points to a whole 20-foot-long wall of books about Lincoln, in one of the four book-lined libraries in her home in Concord, Massachusetts, which she shares with husband Richard Goodwin, and his mementos from his days as speechwriter and adviser to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson—he wrote the “We Shall Overcome” speech that Johnson delivered on national television, in 1965, in heartfelt support of the Voting Rights Act. She worked with Johnson, too, and wrote a book about him. “Lincoln’s ethical and human side still outranks all the other presidents,” she says. “I had always thought of him as a statesman—but I came to realize he was our greatest politician.”

The movie project began with Goodwin’s book, before she had written much of it. When she and Spielberg met, in 1999, he asked her what she was working on, and she said Lincoln. “At that moment,” says Spielberg, “I was impulsively seized with the chutzpah to ask her to let me reserve the motion-picture rights.” To which effrontery she responded, in so many words: Cool. Her original plan had been to write about Mary and Abe Lincoln, as she had about Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. “But I realized that he spent more time with members of his cabinet,” she says.

And so Goodwin’s book became an infectiously loving portrait of Lincoln’s empathy, his magnanimity and his shrewdness, as shown in his bringing together a cabinet of political enemies, some more conservative than he, others more radical, and maneuvering them into doing what needed to be done.

Prominent among those worthies was Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. Goodwin notes that when that august-looking widower and his daughter Kate, the willowy belle of Washington society, “made an entrance, a hush invariably fell over the room, as if a king and his queen stood in the doorway.” And yet, wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, Chase was “destitute of wit.” He could be funny inadvertently. Goodwin cites his confiding to a friend that he “was tormented by his own name. He fervently wished to change its ‘awkward, fishy’ sound to something more elegant. ‘How wd. this name do (Spencer de Cheyce or Spencer Payne Cheyce,)’ he inquired.”

Not only was Chase fatuous, but like Stevens he regarded Lincoln as too conservative, too sympathetic to the South, too cautious about pressing abolition. But Chase was capable, so Lincoln gave him the dead-serious job of keeping the Union and its war effort financially afloat. Chase did so, earnestly and admirably. He also put his own picture on the upper left-hand corner of the first federally issued paper money. Chase was so sure he should have been president, he kept trying—even though Lincoln bypassed loyal supporters to appoint him chief justice of the United States—to undermine Lincoln politically so he could succeed him after one term.

Lincoln was aware of Chase’s treachery, but he didn’t take it personally, because the country needed Chase where he was.

Lincoln’s lack of self-importance extended even further with that pluperfect horse’s ass Gen. George B. McClellan. In 1861, McClellan was using his command of the Army of the Potomac to enhance his self-esteem (“You have no idea how the men brighten up now, when I go among them”) rather than to engage the enemy. In letters home he was mocking Lincoln as “the original gorilla.” Lincoln kept urging McClellan to fight. In reading Goodwin’s book, I tried to identify which of its many lively scenes would be in the movie. Of a night when Lincoln, Secretary of State William Seward and Lincoln’s secretary John Hay went to McClellan’s house, she writes:

Told that the general was at a wedding, the three waited in the parlor for an hour. When McClellan arrived home, the porter told him the president was waiting, but McClellan passed by the parlor room and climbed the stairs to his private quarters. After another half hour, Lincoln again sent word that he was waiting, only to be informed that the general had gone to sleep. Young John Hay was enraged....To Hay’s surprise, Lincoln “seemed not to have noticed it specially, saying it was better at this time not to be making points of etiquette & personal dignity.” He would hold McClellan’s horse, he once said, if a victory could be achieved.

Finally relieved of his command in November 1862, McClellan ran against Lincoln in the 1864 election, on a platform of ending the war on terms congenial to the Confederacy, and lost handily.

It’s too bad Lincoln could not have snatched McClellan’s horse from under him, so to speak. But after the election, notes Tony Kushner, who wrote the screenplay, “Lincoln knew that unless slavery was gone, the war wasn’t really going to end.” So although the movie is based in part on Goodwin’s book, Kushner says, Lincoln didn’t begin to coalesce until Spielberg said, “Why don’t we make a movie about passing the 13th Amendment?”

***

Kushner’s own most prominent work is the greatly acclaimed play Angels in America: angels, Mormons, Valium, Roy Cohn, people dying of AIDS. So it’s not as though he sticks to the tried and true. But he says his first reaction to Spielberg’s amendment notion was: This is the first serious movie about Lincoln in seventy-odd years! We can’t base it on that!

In January 1865, Lincoln has just been re-elected and the war is nearly won. The Emancipation Proclamation, laid down by the president under what he claimed to be special wartime powers, abolishes slavery only within areas “in rebellion” against the Union and perhaps not permanently even there. So while Lincoln’s administration has got a harpoon into slavery, the monster could still, “with one ‘flop’ of his tail, send us all into eternity.”

That turn of metaphor is quoted in Goodwin’s book. But the battle for the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery nationwide and permanently, is confined to 5 of her 754 pages. “I don't like biopics that trot you through years and years of a very rich and complicated life,” Kushner says. “I had thought I would go from September 1863 to the assassination, focusing on the relationship of Lincoln and Salmon Chase. Three times I started, got to a hundred or so pages, and never got farther than January 1864. You could make a very long miniseries out of any week Lincoln occupied the White House.”

He sent Goodwin draft after draft of the script, which at one point was up to 500 pages. “Tony originally had Kate in,” says Goodwin, “and if the film had been 25 hours long....” Then Spielberg brought up the 13th Amendment, which the Chases had nothing to do with.

In the course of six years working on the script, Kushner did a great deal of original research, which kept spreading. For example: “I was looking for a play Lincoln might have seen in early March of ’65...[and] I found a Romeo and Juliet starring Avonia Jones, from Richmond, who was rumored to be a Confederate sympathizer—she left the country immediately after the war, went to England and became an acting teacher, and one of her pupils was Belle Boyd, a famous Confederate spy. And the guy who was supposed to be in Romeo and Juliet with her was replaced at the last moment by John Wilkes Booth—who was plotting then to kidnap Lincoln. I thought, ‘I’ve discovered another member of the conspiracy!’”

Avonia didn’t fit in Lincoln, so she too had to go—but the Nashville lawyer W.N. Bilbo, another one of the obscure figures Kushner found, survived. And as played by James Spader, Bilbo, who appears nowhere in Team of Rivals, nearly steals the show as a political operative who helps round up votes for the amendment, offering jobs and flashing greenbacks to conceivably swayable Democrats and border-state Republicans.

If another director went to a major studio with a drama of legislation, he’d be told to run it over to PBS. Even there, it might be greeted with tight smiles. But although “people accuse Steven of going for the lowest common denominator and that kind of thing,” says Kushner, “he is willing to take big chances.” And nobody has ever accused Spielberg of not knowing where the story is, or how to move it along.

Spielberg had talked to Liam Neeson, who starred in his Schindler’s List, about playing Lincoln. Neeson had the height. “But this is Daniel’s role,” Spielberg says. “This is not one of my absent-father movies. But Lincoln could be in the same room with you, and he would go absent on you, he would not be there, he would be in process, working something out. I don’t know anybody who could have shown that except Daniel.”

On the set everyone addressed Day-Lewis as “Mr. Lincoln” or “Mr. President.” “That was my idea,” Spielberg says. “I addressed all the actors pretty much by the roles they were playing. When actors stepped off the set they could be whoever they felt they needed to be, but physically on the set I wanted everybody to be in an authentic mood.” He never did that in any of his 49 other directorial efforts. (“I couldn’t address Daniel at all,” says Kushner. “I would send him texts. I called myself ‘Your metaphysical conundrum,’ because as the writer of the movie, I shouldn’t exist.”)

Henry Fonda in Young Mister Lincoln (1939) might as well be a youngish Henry Fonda, or perhaps Mister Roberts, with nose enhancement. Walter Huston in Abraham Lincoln (1930) wears a startling amount of lipstick in the early scenes, and later when waxing either witty or profound he sounds a little like W.C. Fields. Day-Lewis is made to resemble Lincoln more than enough for a good poster shot, but the character’s consistency is beyond verisimilitude.

Lincoln, 6-foot-4, was taller than everyone around him by a greater degree than is Day-Lewis, who is 6-foot-1 1/2. I can’t help thinking that Lincoln’s voice was even less mellow (it was described as high-pitched and thin, and his singing was more recitational than melodious) than the workable, vaguely accented tenor that Day-Lewis has devised. At first acquaintance Lincoln came off gawkier, goofier, uglier than Day-Lewis could very well emulate. If we could reconstitute Lincoln himself, like the T. Rex in Jurassic Park, his looks and carriage might put us off.

Day-Lewis gives us a Lincoln with layers, angles, depths and sparks. He tosses in some authentic-looking flat-footed strides, and at one point stretches unpresidentially across the floor he’s lying on to stoke the fire. More crucially, he conveys Lincoln’s ability to lead not by logic or force but by such devices as timing (knowing when a time is ripe), amusement (he not only got away with laughing at his own stories, sometimes for reasons unclear, but also improved his hold on the audience thereby) and at least making people think he was getting into where they were coming from.

We know that Lincoln was a great writer and highly quotable in conversation, but Lincoln captures him as a verbal tactician. Seward (ably played by David Straithairn) is outraged. He’s yelling at Lincoln for doing something he swore he wouldn’t, something Seward is convinced will be disastrous. Lincoln, unruffled, muses about looking into the seeds of time and seeing which grains will grow, and then says something else that I, and quite possibly Seward, didn’t catch, and then something about time being a great thickener of things. There’s a beat. Seward says he supposes. Another beat. Then he says he has no idea what Lincoln’s talking about.

Here’s a more complicated and masterly example. The whole cabinet is yelling at Lincoln. The Confederacy is about to fall, he’s already proclaimed emancipation, why risk his popularity now by pushing for this amendment? Well, he says affably, he’s not so sure the Emancipation Proclamation will still be binding after the war. He doesn’t recall his attorney general at the time being too excited about it being legal, only that it wasn’t criminal. His tone becomes subtly more backwoodsy, and he makes a squeezy motion with his hands. Then his eyes light up as he recalls defending, back in Illinois, a Mrs. Goings, charged with murdering her violent husband in a heated moment.

Melissa Goings is another figure who doesn’t appear in Team of Rivals, but her case is on the record. In 1857, the newly widowed 70-year-old stood accused of bludgeoning her 77-year-old husband with a piece of firewood. In the most common version of the story, Lincoln, sensing hostility in the judge but sympathy among the townspeople, called for a recess, during which his client disappeared. Back in court, the bailiff accused Lincoln of encouraging her to bolt, and he professed his innocence: “I did not run her off. She wanted to know where she could get a good drink of water, and I told her there was mighty good water in Tennessee.” She was never found, and her bail—$1,000—was forgiven.

In the movie, the cabinet members start laughing as Lincoln reminisces, even though they may be trying to parse precisely what the story has to do with the 13th Amendment. Then he shifts into a crisp, logical explication of the proclamation’s insufficiency. In summary he strikes a personal note; he felt the war demanded it, therefore his oath demanded it, and he hoped it was legal. Shifting gears without a hitch, he tells them what he wants from them: to stand behind him. He gives them another laugh—he compares himself to the windy preacher who, once embarked on a sermon, is too lazy to stop—then he puts his foot down: He’s going to sign the 13th Amendment. His lips press so firmly together they tremble just slightly.

Lincoln’s telling of the Goings case varies slightly from the historical record, but in fact there is an account of Lincoln departing from the record himself, in telling the story differently from the way he does in the movie. “The rule was,” says Kushner, “that we wouldn’t alter anything in a meaningful way from what happened.” Conversations are clearly invented, but I haven’t found anything in the movie that is contradicted by history, except that Grant looks too dressy at Appomattox. (Lee does, for a change, look authentically corpulent at that point in his life.)

Lincoln provides no golden interracial glow. The n-word crops up often enough to help establish the crudeness, acceptedness and breadth of anti-black sentiment in those days. A couple of incidental pop-ups aside, there are three African-American characters, all of them based reliably on history. One is a White House servant and another one, in a nice twist involving Stevens, comes in almost at the end. The third is Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker and confidante. Before the amendment comes to a vote, after much lobbying and palm-greasing, there’s an astringent little scene in which she asks Lincoln whether he will accept her people as equals. He doesn’t know her, or her people, he replies. But since they are presumably “bare, forked animals” like everyone else, he says, he will get used to them.

Lincoln was certainly acquainted with Keckley (and presumably with King Lear, whence “bare, forked animals” comes), but in the context of the times, he may have thought of black people as unknowable. At any rate the climate of opinion in 1865, even among progressive people in the North, was not such as to make racial equality an easy sell.

In fact, if the public got the notion the 13th Amendment was a step toward establishing black people as social equals, or even toward giving them the vote, the measure would have been doomed. That’s where Lincoln’s scene with Thaddeus Stevens comes in.

***

Stevens is the only white character in the movie who expressly holds it self-evident that every man is created equal. In debate, he vituperates with relish—You fatuous nincompoop, you unnatural noise!—at foes of the amendment. But one of those, Rep. Fernando Wood of New York, thinks he has outslicked Stevens. He has pressed him to state whether he believes the amendment’s true purpose is to establish black people as just as good as whites in all respects.

You can see Stevens itching to say, “Why yes, of course,” and then to snicker at the anti-amendment forces’ unrighteous outrage. But that would be playing into their hands; borderline yea-votes would be scared off. Instead he says, well, the purpose of the amendment—

And looks up into the gallery, where Mrs. Lincoln sits with Mrs. Keckley. The first lady has become a fan of the amendment, but not of literal equality, nor certainly of Stevens, whom she sees as a demented radical.

The purpose of the amendment, he says again, is—equality before the law. And nowhere else.

Mary is delighted; Keckley stiffens and goes outside. (She may be Mary’s confidante, but that doesn’t mean Mary is hers.) Stevens looks up and sees Mary alone. Mary smiles down at him. He smiles back, thinly. No “joyous, universal evergreen” in that exchange, but it will have to do.

Stevens has evidently taken Lincoln’s point about avoiding swamps. His radical allies are appalled. One asks whether he’s lost his soul; Stevens replies, mildly, that he just wants the amendment to pass. And to the accusation that there’s nothing he won’t say toward that end, he says: Seems not.

Later, after the amendment passes, Stevens pays semi-sardonic tribute to Lincoln, along the lines of something the congressman actually once said: that the greatest measure of the century “was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America.”

That is the kind of purity we “bare, forked animals” can demand of political leaders today, assuming they’re good enough at it.

Of course, Lincoln got shot for it (I won’t spoil for you the movie’s masterstroke, its handling of the assassination), and with that erasure of Lincoln’s genuine adherence to “malice toward none,” Stevens and the other radical Republicans helped make Reconstruction as humiliating as possible for the white South. For instance, Kushner notes, a true-north Congress declined to give Southern burial societies any assistance in finding or identifying remains of the Confederate dead, thereby contributing to a swamp in which equality even before the law bogged down for a century, until nonviolent tricksters worthy of Lincoln provoked President Johnson, nearly as good a politician as Lincoln, to push through the civil rights acts of the 1960s.

How about the present? Goodwin points out that the 13th Amendment was passed during a post-election rump session of Congress, when a number of representatives, knowing they weren't coming back anyway, could be prevailed upon to vote their consciences. "We have a rump session coming up now," she observes.