How Nantucket Came to Be the Whaling Capital of the World

Ron Howard’s new film “In the Heart of the Sea” captures the greed and blood lust of the Massachusetts island

Today Nantucket Island is a fashionable summer resort: a place of T-shirt shops and trendy boutiques. It’s also a place of picture-perfect beaches where even at the height of summer you can stake out a wide swath of sand to call your own. Part of what makes the island unique is its place on the map. More than 25 miles off the coast of Massachusetts and only 14 miles long, Nantucket is, as Herman Melville wrote in Moby-Dick, “away off shore.” But what makes Nantucket truly different is its past. For a relatively brief period during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, this lonely crescent of sand at the edge of the Atlantic was the whaling capital of the world and one of the wealthiest communities in America.

The evidence of this bygone glory can still be seen along the upper reaches of the town’s Main Street, where the cobbles seem to dip and rise like an undulant sea and where the houses—no matter how grand and magisterial—still evoke the humble spirituality of the island’s Quaker past. And yet lurking beneath this almost ethereal surface is the story of a community that sustained one of the bloodiest businesses the world has ever known. It’s a story that I hadn’t begun to fully appreciate until after more than a decade of living on the island when I started researching In the Heart of the Sea, a nonfictional account of the loss of the whaleship Essex, which I revisit here. While what happened to the crew of that ill-fated ship is an epic unto itself—and the inspiration behind the climax of Moby-Dick—just as compelling in its own quintessentially American way is the island microcosm that the Nantucket whalemen called home.

**********

When the Essex departed from Nantucket for the last time in the summer of 1819, Nantucket had a population of about 7,000, most of whom lived on a gradually rising hill crowded with houses and punctuated by windmills and church towers. Along the waterfront, four solid-fill wharves extended more than 100 yards into the harbor. Tied up to the wharves or anchored in the harbor were, typically, 15 to 20 whale ships, along with dozens of smaller vessels, mainly sloops and schooners that carried trade goods to and from the island. Stacks of oil casks lined each wharf as two-wheeled, horse-drawn carts continually shuttled back and forth.

Nantucket was surrounded by a constantly shifting maze of shoals that made the simple act of approaching or departing the island an often harrowing and sometimes disastrous lesson in seamanship. Especially in winter, when storms were the most deadly, wrecks occurred almost weekly. Interred across the island were the corpses of anonymous seamen who had washed onto its wave-pummeled shores. Nantucket—“faraway land” in the language of the island’s native inhabitants, the Wampanoag—was a deposit of sand eroding into an inexorable ocean, and all its residents, even if they had never sailed away from the island, were keenly aware of the inhumanity of the sea.

Nantucket’s English settlers, who first disembarked on the island in 1659, had been mindful of the sea’s dangers. They had hoped to earn their livelihoods not as fishermen but as farmers and shepherds on this grassy isle dotted with ponds, where no wolves preyed. But as the burgeoning livestock herds, combined with the increasing number of farms, threatened to transform the island into a windblown wasteland, Nantucketers inevitably turned seaward.

Every autumn, hundreds of right whales converged to the south of the island and remained until the early spring. Right whales—so named because they were “the right whale to kill”—grazed the waters off Nantucket as if they were seagoing cattle, straining the nutrient-rich surface of the ocean through the bushy plates of baleen in their perpetually grinning mouths. While English settlers at Cape Cod and eastern Long Island had already been pursuing right whales for decades, no one on Nantucket had summoned the courage to set out in boats and hunt the whales. Instead they left the harvesting of whales that washed ashore (known as drift whales) to the Wampanoag.

Around 1690, a group of Nantucketers was gathered on a hill overlooking the ocean where some whales were spouting and frolicking. One of the islanders nodded toward the whales and ocean beyond. “There,” he said, “is a green pasture where our children’s

grandchildren will go for bread.” In fulfillment of the prophecy, a Cape Codder, one Ichabod Paddock, was subsequently lured across Nantucket Sound to instruct the islanders in the art of killing whales.

Their first boats were only 20 feet long, launched from beaches along the island’s south shore. Typically a whaleboat’s crew comprised five Wampanoag oarsmen, with a single white Nantucketer at the steering oar. Once they’d dispatched the whale, they towed it back to the beach, where they sliced out the blubber and boiled it into oil. By the beginning of the 18th century, English Nantucketers had introduced a system of debt servitude that provided a steady supply of Wampanoag labor. Without the native inhabitants, who outnumbered Nantucket’s white population well into the 1720s, the island would never have become a prosperous whaling port.

In 1712, a Captain Hussey, cruising in his little boat for right whales along Nantucket’s south shore, was pushed out to sea in a fierce northerly gale. Many miles out, he glimpsed several whales of an unfamiliar type. This whale’s spout arched forward, unlike a right whale’s vertical spout. In spite of the high winds and rough seas, Hussey managed to harpoon and kill one of the whales, its blood and oil calming the waves in nearly biblical fashion. This creature, Hussey quickly perceived, was a sperm whale, one of which had washed up on the island’s southwest shore a few years earlier. Not only was the oil derived from the sperm whale’s blubber far superior to that of the right whale, providing a brighter and cleaner-burning light, but its block-shaped head contained a vast reservoir of even better oil, called spermaceti, that could simply be ladled into an awaiting cask. (It was spermaceti’s resemblance to seminal fluid that gave rise to the sperm whale’s name.) The sperm whale might have been faster and more aggressive than the right whale, but it was a far more lucrative target. With no other source of livelihood, Nantucketers dedicated themselves to the single-minded pursuit of the sperm whale, and they soon surpassed their whaling rivals on the mainland and Long Island.

By 1760, the Nantucketers had virtually exterminated the local whale population. By that time, however, they had enlarged their whaling sloops and outfitted them with brick tryworks capable of processing the oil on the open ocean. Now, since it was no longer necessary to return to port as often to deliver bulky blubber, their fleet had a far greater range. By the advent of the American Revolution, Nantucketers had reached the verge of the Arctic Circle, the west coast of Africa, the east coast of South America and the Falkland Islands to the south.

In a speech before Parliament in 1775, the British statesman Edmund Burke cited the island’s inhabitants as the leaders of a new American breed—a “recent people” whose success in whaling had exceeded the collective might of all of Europe. Living on an island nearly the same distance from the mainland as England was from France, Nantucketers developed a British sense of themselves as a distinct and exceptional people, privileged citizens of what Ralph Waldo Emerson called the “Nation of Nantucket.”

The Revolution and the War of 1812, when the British Navy preyed upon offshore shipping, proved catastrophic to the whale fishery. Fortunately, Nantucketers possessed sufficient capital and whaling expertise to survive these setbacks. By 1819, Nantucket was well positioned to reclaim and, as the whalers ventured into the Pacific, even overtake its former glory. But the rise of the Pacific sperm whale fishery had a regrettable consequence. Instead of voyages that had once averaged about nine months, two- and three-year voyages had become typical. Never before had the division between Nantucket’s whalemen and their people been so great. Long vanished was the era when Nantucketers could observe from shore as the men and boys of the island pursued the whale. Nantucket was now the whaling capital of the world, but there were more than a few islanders who had never glimpsed a whale.

Nantucket had forged an economic system that no longer depended on the island’s natural resources. The island’s soil had long since been depleted by overfarming. Nantucket’s large Wampanoag population had been reduced to a handful by epidemics, forcing shipowners to look to the mainland for crew. Whales had almost completely disappeared from local waters. And still the Nantucketers prospered. As one visitor observed, the island had become a “barren sandbank, fertilized with whale-oil only.”

**********

Throughout the 17th century, English Nantucketers resisted all efforts to establish a church on the island, partly because a woman named Mary Coffin Starbuck forbade it. It was said that nothing of importance was undertaken on Nantucket without her consent. Mary Coffin and Nathaniel Starbuck had been the first English couple married on the island, in 1662, and had established a profitable outpost for trading with the Wampanoag. Whenever an itinerant minister arrived in Nantucket intending to establish a congregation, he was summarily rebuffed by Mary Starbuck. Then, in 1702, she succumbed to a charismatic Quaker minister, John Richardson. Speaking before a group assembled in the Starbucks’ living room, Richardson succeeded in moving her to tears. It was Mary Starbuck’s conversion to Quakerism that established the unique convergence of spirituality and covetousness that would underlie Nantucket’s rise as a whaling port.

Nantucketers perceived no contradiction between their source of income and their religion. God himself had granted them dominion over the fishes of the sea. Pacifist killers, plain-dressed millionaires, the whalemen of Nantucket (whom Herman Melville described as “Quakers with a vengeance”) were simply enacting the Lord’s will.

On the corner of Main and Pleasant streets stood the Quakers’ immense South Meetinghouse, constructed in 1792 from pieces of the even larger Great Meeting House that once loomed over the stoneless field of the Quaker Burial Ground at the end of Main Street. Instead of an exclusive place of worship, the meetinghouse was open to nearly anyone. One visitor claimed that almost half those who attended a typical meeting (which sometimes attracted as many as 2,000 people—more than a quarter of the island’s population) were not Quakers.

While many of the attendees were there for the benefit of their souls, those in their teens and early 20s tended to harbor other motives. No other place on Nantucket offered a better opportunity for young people to meet members of the opposite sex. Nantucketer Charles Murphey described in a poem how young men such as himself used the long intervals of silence typical of a Quaker meeting:

To sit with eager eyes directed

On all the beauty there collected

And gaze with wonder while

in sessions

On all the various forms

and fashions.

**********

No matter how much this nominally Quaker community might attempt to conceal it, there was a savagery about the island, a blood lust and pride that bound every mother, father and child in a clannish commitment to the hunt. The imprinting of a young Nantucketer commenced at the earliest age. The first words a baby learned included the language of the chase—townor, for instance, a Wampanoag word signifying that the whale has been sighted for a second time. Bedtime stories told of killing whales and eluding cannibals in the Pacific. One mother approvingly recounted that her 9-year-old son affixed a fork to a ball of darning cotton and then went on to harpoon the family cat. The mother entered the room just as the terrified pet attempted to escape, and unsure of what she had found herself in the middle of, she picked up the cotton ball. Like a veteran boatsteerer, the boy shouted, “Pay out, mother! Pay out! There she sounds through the window!”

There was rumored to exist a secret society of young women on the island whose members vowed to wed only men who had already killed a whale. To help these young women identify them as hunters, boatsteerers wore chockpins (small oak pins used to secure the harpoon line in the bow groove of a whaleboat) on their lapels. Boatsteerers, outstanding athletes with prospects of lucrative captaincies, were considered the most eligible Nantucket bachelors.

Instead of toasting a person’s health, a Nantucketer offered invocations of a darker sort:

Death to the living,

Long life to the killers,

Success to sailors’ wives

And greasy luck to whalers.

Despite the bravado of this little ditty, death was a fact of life all too familiar among Nantucketers. In 1810 there were 472 fatherless children on Nantucket, while nearly a quarter of the women over the age of 23 (the average age of marriage) had lost their husbands to the sea.

Perhaps no community before or since has been so divided by its commitment to work. For a whaleman and his family, it was a punishing regimen: two to three years away, three to four months at home. With their men absent for so long, Nantucket’s women were obliged not only to raise the children but also to oversee many of the island’s businesses. It was women for the most part who maintained the complex web of personal and commercial relationships that kept the community functioning. The 19th-century feminist Lucretia Coffin Mott, who was born and raised on Nantucket, remembered how a husband returned from a voyage commonly followed in the wake of his wife, accompanying her to get-togethers with other wives. Mott, who eventually moved to Philadelphia, commented on how odd such a practice would have seemed to anyone from the mainland, where the sexes operated in entirely distinct social spheres.

Some of the Nantucket wives adapted readily to the rhythm of the whale fishery. The islander Eliza Brock recorded in her journal what she called the “Nantucket Girl’s Song”:

Then I’ll haste to wed a sailor,

and send him off to sea,

For a life of independence,

is the pleasant life for me.

But every now and then I shall

like to see his face,

For it always seems to me to beam with manly grace....

But when he says “Goodbye my love, I’m off across the sea,”

First I cry for his departure, then laugh because I’m free.

**********

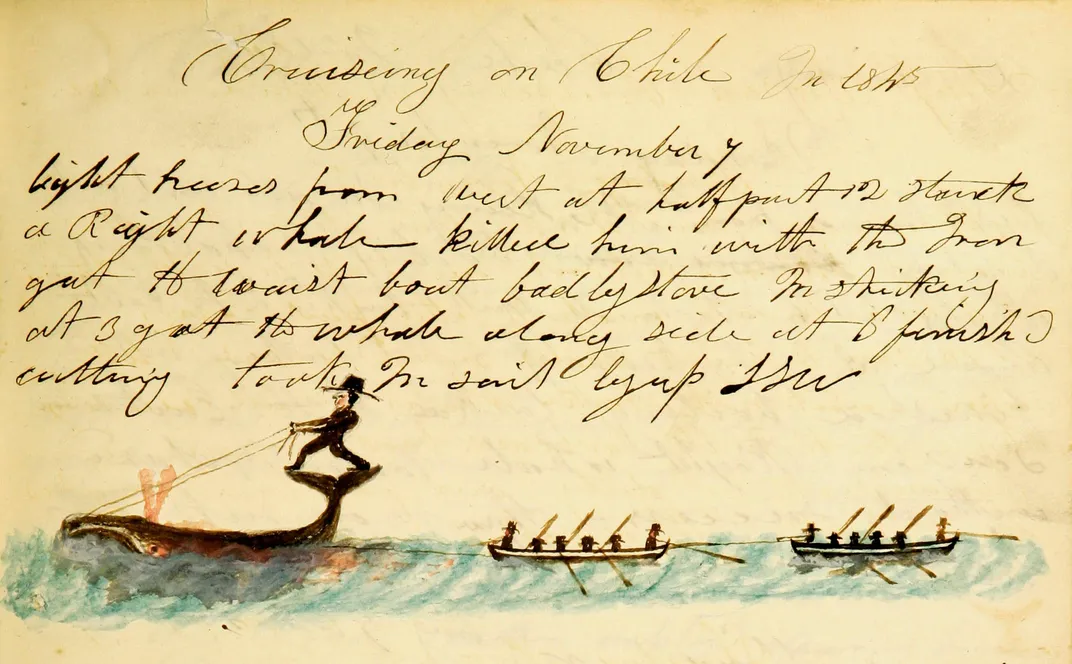

As their wives and sisters conducted their lives back on Nantucket, the island’s men and boys pursued some of the largest mammals on earth. In the early 19th century a typical whaleship had a crew of 21 men, 18 of whom were divided into three whaleboat crews of six men each. The 25-foot whaleboat was lightly built of cedar planks and powered by five long oars, with an officer standing at the steering oar on the stern. The trick was to row as close as possible to their prey so that the man at the bow could hurl his harpoon into the whale’s glistening black flank. More often than not the panicked creature hurtled off in a desperate rush, and the men found themselves in the midst of a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” For the uninitiated, it was both exhilarating and terrifying to be pulled along at a speed that approached as much as 20 miles an hour, the small open boat slapping against the waves with such force that the nails sometimes started from the planks at the bow and stern.

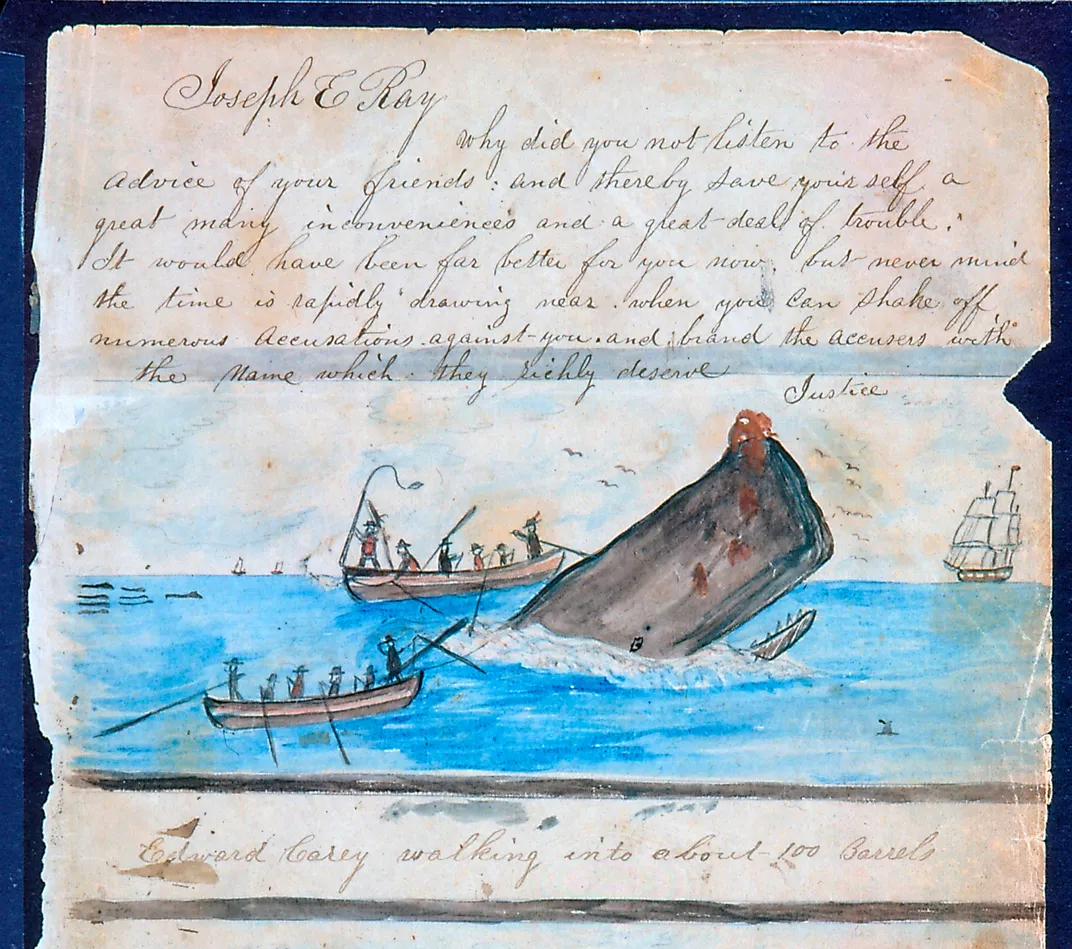

The harpoon did not kill the whale. It was the equivalent of a fishhook. After letting the whale exhaust itself, the men began to haul themselves, inch by inch, to within stabbing distance of the whale. Taking up the 12-foot-long killing lance, the man at the bow probed for a group of coiled arteries near the whale’s lungs with a violent churning motion. When the lance finally plunged into its target, the whale would begin to choke on its own blood, its spout transformed into a 15-foot geyser of gore that prompted the men to shout, “Chimney’s afire!” As the blood rained down on them, they took up the oars and backed furiously away, then paused to observe as the whale went into what was known as its “flurry.” Pounding the water with its tail, snapping at the air with its jaws, the creature began to swim in an ever-tightening circle. Then, just as abruptly as the attack had begun with the initial harpoon thrust, the hunt ended. The whale fell motionless and silent, a giant black corpse floating fin up in a slick of its own blood and vomit.

Now it was time to butcher the whale. After laboriously towing the corpse back to the vessel, the crew secured it to the ship’s side, the head toward the stern. Then began the slow and bloody process of peeling five-foot-wide strips of blubber from the whale; the sections were then hacked into smaller pieces and fed into the two immense iron trypots mounted on the deck. Wood was used to start the fires beneath the pots, but once the boiling process had commenced, crisp pieces of blubber floating on the surface were skimmed off and tossed into the fire for fuel. The flames that melted down the whale’s blubber were thus fed by the whale itself and produced a thick pall of black smoke with an unforgettable stench—“as though,” one whaleman remembered, “all the odors in the world were gathered together and being shaken up.”

**********

During a typical voyage, a Nantucket whaleship might kill and process 40 to 50 whales. The repetitious nature of the work—a whaler was, after all, a factory ship—desensitized the men to the awesome wonder of the whale. Instead of seeing their prey as a 50- to 60-ton creature whose brain was close to six times the size of their own (and, what perhaps should have been even more impressive in the all-male world of the fishery, whose penis was as long as they were tall), the whalemen preferred to think of it as what one observer described as “a self-propelled tub of high-income lard.” In truth, however, the whalemen had more in common with their prey than they would have ever cared to admit.

In 1985 the sperm whale expert Hal Whitehead used a cruising sailboat fitted with sophisticated monitoring equipment to track sperm whales in the same waters that the Essex plied in the summer and fall of 1820. Whitehead found that the typical pod of whales, which ranges between 3 and 20 or so individuals, comprised almost exclusively interrelated adult females and immature whales. Adult males made up only 2 percent of the whales he observed.

The females work cooperatively in taking care of their young. The calves are passed from whale to whale so that an adult is always standing guard when the mother is feeding on squid thousands of feet below the ocean’s surface. As an older whale raises its flukes at the beginning of a long dive, the calf will swim to another nearby adult.

Young males depart the family unit at around 6 years of age and make their way to the cooler waters of the high latitudes. Here they live singly or with other males, not returning to the warm waters of their birth until their late 20s. Even then, a male’s return is fairly transient; he spends only eight or so hours with any particular group, sometimes mating but never establishing strong attachments, before returning to the high latitudes.

The sperm whales’ network of female-based family units resembled, to a remarkable degree, the community the whalemen had left back home on Nantucket. In both societies the males were itinerants. In their pursuit of killing sperm whales the Nantucketers had developed a system of social relationships that mimicked those of their prey.

**********

Herman Melville chose Nantucket to be the port of the Pequod in Moby-Dick, but it would not be until the summer of 1852—almost a year after publication of his whaling epic—that he visited the island for the first time. By then Nantucket’s whaling heyday was behind it. The mainland port of New Bedford had assumed the mantle as the nation’s whaling capital, and in 1846 a devastating fire destroyed the island’s oil-soaked waterfront. The Nantucketers quickly rebuilt, this time in brick, but the community had begun a decades-long descent into economic depression.

Melville, it turned out, was experiencing his own decline. Despite being regarded today as a literary masterpiece, Moby-Dick was poorly received by both critics and the reading public. In 1852, Melville was a struggling writer in desperate need of a holiday, and in July of that year he accompanied his father-in-law, Justice Lemuel Shaw, on a voyage to Nantucket. They likely stayed at what is now the Jared Coffin House at the corner of Center and Broad streets. Diagonally across from Melville’s lodgings was the home of none other than George Pollard Jr., the former captain of the Essex.

Pollard, as it turned out, had gone to sea again after the loss of the Essex, as captain of the whaleship Two Brothers. That ship went down in a storm in the Pacific in 1823. All the crew members survived, but, as Pollard confessed during the return voyage to Nantucket, “No owner will ever trust me with a whaleship again, for all will say I am an unlucky man.”

By the time Melville visited Nantucket, George Pollard had become the town’s night watchman, and at some point the two men met. “To the islanders he was a nobody,” Melville later wrote, “to me, the most impressive man, tho’ wholly unassuming even humble—that I ever encountered.” Despite having suffered the worst of all possible disappointments, Pollard, who retained the watchman position until the end of his life in 1870, had managed a way to continue on. Melville, who was doomed to die almost 40 years later in obscurity, had recognized a fellow survivor.

**********

In February 2011—more than a decade after publication of my book In the Heart of the Sea—came astonishing news. Archaeologists had located the underwater wreck of a 19th-century whaling vessel and solved a Nantucket mystery. Kelly Gleason Keogh was wrapping up a monthlong expedition in the remote Hawaiian Islands when she and her team indulged in some last-minute exploring. They set out to snorkel the waters near Shark Island, an uninhabited speck 600 miles northwest of Honolulu. After 15 minutes or so, Keogh and a colleague spotted a giant anchor some 20 feet below the surface. Minutes later, they came upon three trypots—cast-iron cauldrons used by whalers to render oil from blubber.

“We knew we were definitely looking at an old whaling ship,” says Keogh, 40, a maritime archaeologist who works for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument—at 140,000 square miles, the largest protected marine conservation area in the United States. Those artifacts, the divers knew, indicated that the ship likely came from Nantucket in the first half of the 19th century. Could it be, Keogh wondered, that they had stumbled across the long-lost Two Brothers, infamous in whaling history as the second vessel that Capt. George Pollard Jr. managed to lose at sea?

The Two Brothers—a 217-ton, 84-foot-long vessel built in Hallowell, Maine, in 1804—also carried two other Essex survivors, Thomas Nickerson and Charles Ramsdell. The ship departed Nantucket on November 26, 1821, and followed an established route, rounding Cape Horn. From the western coast of South America, Pollard sailed to Hawaii, making it as far as the French Frigate Shoals, an atoll in the island chain that includes Shark Island. The waters, a maze of low-lying islands and reefs, were treacherous to navigate. The entire area, Keogh says, “acted a bit like a ship trap.” Of the 60 vessels known to have gone down there, ten were whaleships, all of which sank during the peak of Pacific whaling, between 1822 and 1867.

Bad weather had thrown off Pollard’s lunar navigation. On the night of February 11, 1823, the sea around the ship suddenly churned white as the Two Brothers hurtled against a reef. “The ship struck with a fearful crash, which whirled me head foremost to the other side of the cabin,” Nickerson wrote in an eyewitness account he produced some years after the shipwreck. “Captain Pollard seemed to stand amazed at the scene before him.” First mate Eben Gardner recalled the final moments: “The sea made it over us and in a few moments the ship was full of water.”

Pollard and the crew of about 20 men escaped in two whaleboats. The next day, a vessel sailing nearby, the Martha, came to their aid. The men all eventually returned home, including Pollard, who knew that he was, in his words, “utterly ruined.”

Wrecks of old wooden sailing ships seldom resemble the intact hulks seen in movies. Organic materials such as wood and rope break down; only durable objects, including those made from iron or glass, remain. The waters off the northwestern Hawaiian Islands are particularly turbulent; Keogh compares diving there to being tumbled inside a washing machine. “The wave actions, the salt water, the creatures underwater have all taken their toll on the shipwreck,” she says. “A lot of things after 100 years on the seafloor don’t look like man-made objects anymore.”

The remains of Pollard’s ship went undisturbed for 185 years. “No one had gone searching for these things,” Keogh says. Following the discovery, Keogh traveled to Nantucket, where she conducted extensive archival research on the Two Brothers and its unfortunate captain. The following year she returned to the site and followed a trail of sunken bricks (originally used as ballast) to discover a definitive clue to the ship’s identity—harpoon tips that matched those produced in Nantucket during the 1820s. (The Two Brothers was the only Nantucket whaler shipwrecked in these waters in that decade.) That finding, Keogh says, was the smoking gun. After a visit to the site turned up shards of cooking pots that matched advertisements in Nantucket newspapers from that era, the team announced its discovery to the world.

Nearly two centuries after the Two Brothers departed Nantucket, the objects aboard the ship have returned to the island. They are featured in an interactive exhibition chronicling the saga of the Essex and her crew, “Stove by a Whale,” at the Nantucket Whaling Museum. The underwater finds, says Michael Harrison of the Nantucket Historical Association, are helping historians to “put some real bones to the story” of the Two Brothers.

The underwater investigation will continue. Archaeologists have found hundreds of other artifacts, including blubber hooks, additional anchors, the bases of gin and wine bottles. According to Keogh, she and her team were lucky to have spotted the site when they did. Recently, a fast-growing coral has encased some items on the seafloor. Even so, Keogh says, discoveries may yet await. “Sand is always shifting at the site,” she says. “New artifacts may be revealed.”

**********

In 2012 I received word of the possibility that my book might be made into a movie starring Chris Hemsworth and directed by Ron Howard. A year after that, in November 2013, my wife, Melissa, and I visited the set at the Warner Brothers lot in Leavesden, England, about an hour outside London. There was a wharf extending out into a water tank about the size of two football fields, with an 85-foot whaleship tied up to the pilings. Amazingly authentic buildings lined the waterfront, including a structure that looked almost exactly like the Pacific National Bank at the head of Main Street back on Nantucket. Three hundred extras walked up and down the muddy streets. After having once tried to create this very scene through words, it all seemed strangely familiar. I don’t know about Melissa, but at that moment I had the surreal sense of being—even though I was more than 3,000 miles away—home.

Additional reporting by Max Kutner and Katie Nodjimbadem.

**********