A New Oral History Project Seeks the Stories of World War II Before It’s Too Late

Every member of the greatest generation has a tale to tell, no matter what they did during the war

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/d1/c5d14569-e010-48df-bf6f-ebe90c7b5ede/img542502262.jpg)

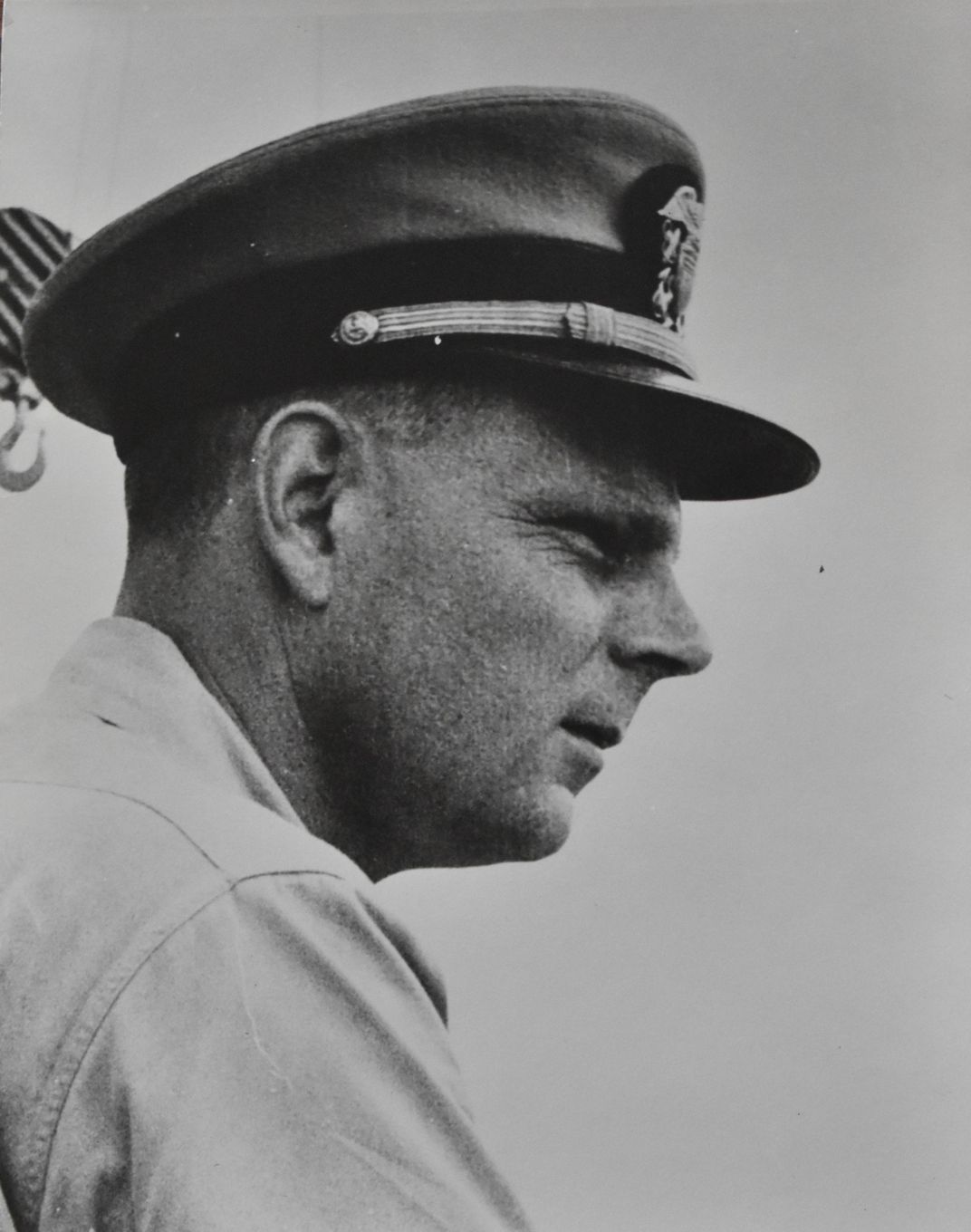

On December 7, 1941, a young Navy Junior named Tom Noble got a call in Honolulu. His father, a naval officer who had been temporarily transferred to the USS Detroit, wouldn't be home that day, said a family friend—something was going on at Pearl Harbor. It was "a strange exercise," Noble recalled. "He said they've even spread oil on Hickam Field and set it afire, very realistic drill."

This was no drill. World War II had just burst into flames. On that day, Noble and his family became part of the United States' vast home front—a victory-oriented war machine that needed its civilians as much as its military.

Noble's father survived the attack, but life changed swiftly as the war progressed. The Nobles painted their windows black and filled their bathtubs with water when false rumors circulated that the Japanese had poisoned their reservoirs. They rationed whiskey and were eventually evacuated from Hawaii.

When Noble came of age, he became a naval officer like his father and served for over 20 years. His memories of the war include his father's military service, but also many not-so-ordinary moments of life as a civilian amid rattling plates and panicked adults, police radios and rationing. He's not alone: Tens of millions of Americans who lived through the war are still alive today.

Now, an unusual oral history project is asking them to tell their stories. It's called The StoryQuest Project, and so far it has captured over 160 stories from both veterans and civilians about their experiences during the war. At first glance, the project seems similar to those of other institutions that collect oral histories. But in the case of StoryQuest, it's as much about who collects the histories as what those stories contain.

Historians, archivists and graduate students aren't at the heart of the project. Rather, the research team consists of undergrads from C.V. Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience at Washington College, where the project is based. Undergraduates receive training in oral history, interview people like Tom Noble about their experiences during the war, then transcribe and preserve the interviews for the future. Along the way, they develop oral history, technology and critical thinking skills.

It goes deeper than that, though, says Adam Goodheart, a historian who directs the C.V. Starr Center and oversees the project. "A key to the success of this program is that it involves 19-year-olds sitting down with 90-year-olds," says Goodheart. "An older person often is more comfortable sharing stories with people from that very young generation than they are with people closer in age to them. When they sit down with a group of people who look a lot like their grandchildren, they have a sense of passing along their story to a new generation."

Undergraduates are often the same age as interviewees were during World War II, he adds—and their presence helps ensure that the speaker takes nothing for granted.

StoryQuest's young interviewers elicit fascinating stories of the everyday. Interviewees have told them about their childhood fears of what Germans might do to kids if they invaded the Eastern Seaboard, how bubble gum was rationed, and how toilet paper fell from the sky on V-J Day. They have shared what it was like when family members didn't come back from the war and how their families responded to calls to grow their own food and host war workers in their homes. And their stories of lesser-known home fronts like Panama and America's long-forgotten camps for German prisoners of war bring to life facets of the war that might otherwise be forgotten.

It's not enough to simply collect the stories, says Goodheart—part of the program's imperative is to preserve and publicize them. To that end, StoryQuest participants are working to create a publicly accessible database of transcripts and audio files for whomever wishes to use them. (Right now only selected excerpts are available online.) The stories will be permanently housed in the college's archives. StoryQuest also plans to take its concept to other institutions in the hopes that even more students can collect World War II stories before it's too late.

"What good are all of these cultural treasures unless other people can learn from them?" says Alisha Perdue, corporate responsibility community manager at Iron Mountain. Perdue, who oversees the multinational information management company's charitable giving and partnerships, reached out to Goodheart and his team after hearing about the project online. "We were particularly drawn to the fact that they're collecting veteran's stories and the stories of people who might be lesser known for their contributions [during World War II]," she says. The company now provides financial sponsorship and strategic support to the growing project.

StoryQuest faces two big challenges as it moves forward. The first is time: Many of those who remember the era are simply dying off. "It's about to slip completely out of reach," says Goodheart. He hopes that as survivors realize that their numbers are dwindling, they'll become more eager to share their stories.

But the biggest struggle of all is interviewees' reluctance to see themselves as part of history. "A lot of these folks don't think that their stories are important," says Goodheart. "It's a challenge to get them to the point where they feel like their own personal history has value and importance beyond themselves."

Noble agrees. "I was a young teenager during the war—not a true veteran," he tells Smithsonian.com. "I thought it wasn't really what they were looking for." But over the course of the interview, he was able to open up about his wartime experiences, even tearing up as he described the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Now, says Noble, he sees the value of sharing his story. "Now that we have email, people aren't handwriting any more," he says. "I think these oral history things are important, not because of us, but because of somebody downstream, 30 or 40 years later."

Then he catches himself. Seventy-five years later. "I had no trouble recalling it," he says, his voice quiet. "It was at the top of my head."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)