Samuel Adams delivered what may count as the most remarkable second act in American life. It was all the more confounding after the first: He was a perfect failure until middle age. He found his footing at 41, when, over a dozen years, he proceeded to answer to Thomas Jefferson’s description of him as “truly the man of the Revolution.” With singular lucidity Adams plucked ideas from the air and pinned them to the page, layering in the moral dimensions, whipping up emotions, seizing and shaping the popular imagination.

On a wet night in 1774, when a group of Massachusetts farmers settled in a tavern before the fire and, pipes in hand, discussed what had driven Bostonians mad—reasoning that Parliament might soon begin to tax horses, cows and sheep; wondering what additional affronts could come their way; and concluding that it was better to rebel sooner rather than later—it was because the long arm of Adams had reached them. He muscled words into deeds, effecting, with various partners, a revolution that culminated, in 1776, with the Declaration of Independence. It was a sideways, looping, secretive business. Adams steered New Englanders where he was certain they meant, or should mean, to head, occasionally even revealing the destination along the way. As a grandson acknowledged: “Shallow men called this cunning, and wise men wisdom.” The patron saint of late bloomers, Adams proved a political genius.

John Adams swore that his cousin Samuel was born to sever the cord between Great Britain and America. John also believed Samuel an original; Samuel mystified even his peers. Serene, sunny, tender, he seemed instinctively to grasp what righteous anger could accomplish. From four feckless decades he emerged intensely disciplined, an indomitable master of public opinion. In a colony from which, as a Crown officer observed, “all the smoke, flame and lava” erupted, Samuel Adams seemed everywhere at once. If there was a subversive committee in Massachusetts, he sat on it. If there was a subversive act, he was somewhere near or behind it. “He eats little, drinks little, sleeps little, thinks much, and is most decisive and indefatigable in the pursuit of his objects,” a Philadelphia colleague noted, unhappily. His enemies, insisted Samuel, came in handy: “Our friends are either blind to our faults or not faithful enough to tell us of them.” He knew that we are governed more by our feelings than by reason; with rigorous logic, he lunged at the emotions. He made a passion of decency. He was a prudent revolutionary. Among the last of his surviving words is a warning to Thomas Paine: “Happy is he who is cautious.”

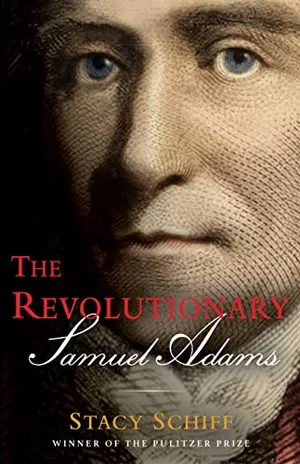

The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams

Stacy Schiff tells the story of Adams’ improbable life, illuminating his transformation from aimless son of a well-off family to tireless, beguiling radical who mobilized the colonies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1d/10/1d10c89a-b77a-4b32-93fc-dc481847ab61/oct2022_i05_samadams.jpg)

Deeply idealistic—a moral people, Adams held, would elect moral leaders—he believed virtue the soul of democracy. To have a villainous ruler imposed on you was a misfortune. To elect him yourself was a disgrace. At the same time, he was unremittingly pragmatic. Adams saw no reason that high-minded ideals should shy from underhanded tactics. Power worried him; no one ever believed he possessed too much of the stuff. His sympathies lay with the man in the street, to whom he believed government answered. A friend reduced Adams’ politics to two maxims: “Rulers should have little, the people much.” And privilege should make way for genius and industry. Railing against “the odious hereditary distinction of families,” Adams fretted about vanity, frivolity and “political idolatry.” He did his best to contain himself when his colleague John Hancock—who traveled with “the pomp and retinue of an Eastern prince”—appeared in a gold-trimmed, crimson-velvet waistcoat and an embroidered white vest. In 1794, Adams was inaugurated as governor of Massachusetts. To maintain ceremonial standards, a benefactor produced a carriage. Adams directed the coachman to drive his wife to the State House, to which he proceeded, at 71, on foot.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8c/04/8c04eb9a-a842-4299-ae62-8a28dfe2c264/oct2022_i04_samadams.jpg)

On no count did he mystify more than in his disregard for money. “I glory in being what the world calls a poor man. If my mind has ever been tinctured with envy, the rich and the great have not been its objects,” he wrote his wife of 16 years, who hardly needed a reminder. At a precarious point, she supported the family. Having dissipated a fortune, having run his father’s malt business into the ground, having contracted massive debts, Adams lived on air, or on what closer inspection revealed to be the charity of friends. A rarity in an industrious, hard-driving, aspirational town, he was the only member of his Harvard class to whom no profession could be ascribed. Certainly no one turned up at the Second Continental Congress as ill-dressed as Adams, who for some weeks wore the suit in which he dove into the woods near Lexington, hours before the battle. It was shabby to begin with. Alone among our founders, his is a riches-to-rags story.

There was an elemental purity about the man whom Crown officers believed the greatest incendiary in the king’s dominion. Puritan simplicity never lost its appeal; afflictions invigorated. Adams handily beat Ben Franklin at Franklin’s 13-point project for arriving at moral perfection. On meeting Adams in the 1780s, a foreigner marveled: It was unusual, in life or on the stage, for anyone to conform so neatly to the role he played. Here was what a republican looked like.

In July 1774, newly arrived in London and reeling still from seasickness, Thomas Hutchinson, the royal governor of Massachusetts, was whisked off for a private interview with George III. For two hours, Hutchinson briefed his sovereign on American affairs. The king seemed as eager to show off his knowledge as to learn what was happening in the most unruly of his American colonies. He asked about Indian extinction and the composition of New England bread. He had heard of Adams but had not grasped that he was the cause of so many royal headaches. Hutchinson revealed that Adams was “a great man of the party.” What gave him his influence? inquired the king. “A great pretended zeal for liberty, and a most inflexible natural temper,” Hutchinson explained, adding that Adams had been the first to advocate for American independence.

Making the same point differently, Jefferson called Adams “the earliest, most active and persevering man of the Revolution.” For many years it was possible to assert that he ranked with, if not above, George Washington. His fame spread alongside New England obstreperousness, which he hoped to make contagious. “Very few have fortitude enough,” Adams wrote, neatly summarizing his life’s work, “to tell a tyrant they are determined to be free.” Various patriots made their mark as the Samuel Adams of North Carolina, the Samuel Adams of Rhode Island, or the Samuel Adams of Georgia. “The character of your Mr. Samuel Adams runs very high here. I find many who consider him the first politician in the world,” a Bostonian reported from 1774 London. John Adams was met with a hero’s welcome when he arrived in France four years later to help solicit an alliance. He hurried to clarify: He was not the renowned Mr. Adams. That was another gentleman. (No one believed him.) “Without the character of Samuel Adams,” declared John, “the true history of the American Revolution can never be written.”

And yet it was, for various reasons. Samuel Adams engaged in a delicate, dangerous business. He was in the eyes of the British administration for years a near-outlaw, ultimately an actual outlaw. Had events turned out differently he would have been first to the gallows. Much of his work depended on plausible deniability. He covered tracks and erased fingerprints. He made no copies of his letters. John Adams watched helplessly in 1770s Philadelphia as his cousin fed whole handfuls of papers to the fire in his room. Was he perhaps overreacting? asked John. “Whatever becomes of me,” Samuel explained, “my friends shall never suffer by my negligence.” In the summer, he used scissors to cut bundles of letters to shreds and scattered the confetti from the window, sparing his associates if stopping the biographer’s heart. A portion of what he did not manage to destroy met with some mistreatment, of which we have only hints. He operated by stealth, melting into committees and crowd actions, pseudonyms and smoky back rooms. “There ought to be a memorial to Samuel Adams in the CIA,” quips a modern historian, dubbing him America’s first covert agent. We are left to read him in the twisted arm, the borrowed set of talking points, the indignation of America’s enemies. We know more about him from his apoplectic adversaries than from his friends, sworn to secrecy.

Unlike his contemporaries, Adams did not preen for posterity. He wrote no memoir, resisting even calls to assemble his political writings. He left the history to others, with predictable results, the more so as his ideas diverged from those of post-Revolutionary America, where he wound up intellectually homeless. Sometimes history blossoms after the fact, and sometimes it evaporates. Adams escaped the golden haze that settled around his fellow founders, as if it were too extravagant for him. He hailed from the messy, anarchic, provocative years. It would not help that he would be confused with John, who collected his own letters, wrote prolifically for the record, and, since adolescence, had rehearsed for greatness.

Adams was rare for his ability to keep a secret, any number of which he took to the grave, including the backstory of the Boston Tea Party, which he knew as well as anyone. (Dryly he noted that some individuals enjoyed every political gift except that of discretion.) He freely discussed his limitations, reminding friends that he understood nothing of military matters, commerce or ceremony, though Congress charged him, at various times, with all three. Most of America’s founders became giants after independence. Adams began to shrink. A cloud of notoriety survives him. The fame does not; he would be minimized in any number of ways. He is the sole signer of the Declaration of Independence to come down to us as an incendiary, and a beer.

Throughout the 1760s, Adams warned of and watched for imperial overreach. The Americans should resist all blandishments; their rights stood in danger. That was before the royal governor of Massachusetts requested troops to maintain order in restive Boston. Crown officials had been terrorized; the home of Thomas Hutchinson, then lieutenant governor, had been sacked; the newspapers bristled with sedition. To much consternation, two regiments materialized in the harbor late in 1768. In a massive military parade, bayonets fixed, flags flying, fifes and drums playing, redcoats marched into central Boston on October 1. A train of artillery followed behind. At least for the next weeks the town went uncharacteristically quiet. Crown officials reported that they had not slept so well in years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/32/18/3218bd3e-ca81-483a-81aa-2f68b9731191/oct2022_i01_samadams.jpg)

At the same time, occupation moved Adams to the moral high ground. Was it not an insult for a free people to be surrounded by men of war, the streets invaded by soldiers? Two additional regiments soon washed up in Boston, which added up to a redcoat for nearly every adult man. Tensions mounted weekly, exacerbated by Adams and his friends, who advertised the troops’ antics, real and fictional. Adams pronounced himself pleased that by the following winter even women and children had begun to ridicule the occupiers, plundering the New England vocabulary for every insult, blasting redcoats with “all the abusive language they could invent.” The soldiers were “bloody-back thieving dogs” or “damned rascally scoundrel lobster sons of bitches.” They were stalked, threatened, hissed at, knocked down, pelted with stones, mud, spittle, snowballs and pieces of brick, dismissed by the magistrates to whom they took their complaints. Boston made trophies of their swords and epaulets. The town was a tinderbox well before the first week of March 1770 when—ill humor pooling all around—a brawl erupted steps from Adams’ front door.

Around a steaming tar kettle, ropewalk workers exchanged blows with grenadiers from the 29th Regiment. The soldiers battled with cutlasses and clubs, the workers with long sticks used to twist lengths of hemp. They went four rounds. Though considerably outnumbered, the ropeworkers drove off the soldiers. Scuffles continued through the weekend, as cutlasses flashed and insults flew. By Sunday a cudgel had, too. One British soldier wound up with a fractured arm and skull. Mutters of revenge circulated. In a shop, a grenadier’s wife crowed that before Tuesday the soldiers would wet their swords in New England blood. The maid who spent her Sunday near the ropewalks heard there would be a fight the following evening. Ringing bells would signal a brawl rather than a fire, information she did not share with Hutchinson, her employer and the acting governor. His council did, warning that “it was apprehended that the smaller frays would be followed by one more general.” Later in the year Adams would claim that soldiers—gloating that blood would soon run through the streets—promised “that many who would dine on Monday would not breakfast on Tuesday.”

Early on the evening of March 5, 1770, under a slim moon, parties of soldiers could be seen prowling about. According to Adams, they carried a variety of weapons. The town’s winding lanes crackled with tension as, amid drifts of fresh snow, Boston came alive. Blows were exchanged in several neighborhoods. A crowd collected in central Boston, on King Street, near the customs house; they hurled snowballs, oyster shells and chunks of ice at a sentry, taunting him and creating a commotion. Earlier he had tangled with a few boys, whom he attempted to strike with the end of his gun. Whistling and shrieking, the boys returned with friends. The sentry cried out for assistance. Thomas Preston, the regimental captain, rushed to his side, accompanied by seven men. They and their bayonets electrified the crowd.

Preston ordered his soldiers to level their guns. The townspeople surged toward the jagged semi-circle, pressing closely upon the redcoats, nearly impaling themselves. A hat would not fit between the soldiers and the civilians, too close to hurl anything but words—as they did, from every direction. Their backs to the brick customs house wall, the soldiers found themselves surrounded on three sides by jeering Bostonians, pushing and shoving, the ground slippery underfoot. “God damn you, fire and be damned; we know you dare not,” they shouted, whistling at the “cowardly rascals” and attempting to knock muskets free. Overhead, the bells began to toll. Moonlight glinted on the weapons. A concerned citizen maneuvered his way through the crowd. A hand on Preston’s crimson-coated shoulder, he asked if the soldiers’ guns were loaded. They were. Did the captain intend to fire upon the inhabitants? By no means, Preston replied, as he must truly have believed. He stood directly in front of his men.

No sooner had he spoken than a stick slashed through the air, sending a grenadier sprawling across the ice. A shot rang out. Seconds or minutes later came another crackle of musket fire. Cries of “To arms, to arms!” filled the air. The town drums beat for a militia. Bells rang frantically. Many scrambled home for guns. Some cowered behind frosted windows. Others rushed to King Street. The crowd swelled to more than a thousand.

Before the situation deteriorated further, someone had the good sense to sprint the half mile to Hutchinson’s house to alert the acting governor. The town was in an uproar. The sight of dead bodies and crimson snow had made it wild. There would soon be carnage everywhere. On Boston’s south side, the bells interrupted a meeting of a small social club. Its members snatched hats and coats and ran out to assist, they too evidently assumed, in quenching a fire: Bells rang in the night for only one reason. John Adams was among the club members who joined the throng streaming toward King Street. His cousin may have been as well. Only amid the pandemonium—the bells clanging furiously—did they understand why some had traded buckets for clubs and canes. Soldiers had fired upon civilians. The good citizen who had confronted Preston nursed a scorched sleeve. Blood splattered the waistcoats of bystanders. It stained fingers. It gushed from a massive wound in a victim’s head. At least one man gasped for breath on the ground. Another was lifeless.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/07/b8/07b825b4-56af-4912-966a-1e01ac56cb01/oct2022_i09_samadams.jpg)

In the street, Hutchinson saw sticks and cutlasses; he would not know until afterward about the club that had been lifted over his head, then quietly snatched away. With difficulty he was conveyed through back alleys to King Street, where he attempted to shout his way through a conversation with Preston. Had the captain ordered his men to fire on civilians? Hutchinson crossly demanded. Preston replied with equal sharpness. The men had fired of their own accord, though in the commotion Hutchinson could not make out his words. Later there would be other difficulties in obtaining explanations; Hutchinson would say that there were so many disparate accounts of the evening that he could not possibly supply a true one with all the time in the world.

Swept up the stairs to the balcony of the Town House, the seat of colonial government, he pleaded with the crowd below. He promised a full and impartial inquiry. Nothing further could be done that evening. At length he prevailed on the throng to retire; only a small huddle refused, their breaths misting the icy darkness. Hutchinson immediately began to depose witnesses. By 1 a.m. he had arranged for the regiments to return to their barracks. By 2 a.m. he had arrested Preston. The eight soldiers who had either fired or not fired joined him in prison. By 4 a.m. the town was quiet. Hutchinson knew early on there were two casualties; by dawn there would be another. Five men were killed and six wounded. A 47-year-old Black sailor had been shot twice in the chest. Two bullets in his back, a ship’s mate had died on the spot. By the time Adams got his hands on events, it had been their misfortune to have faced hooligans “with guns loaded and bayonets fixed, trembling with rage, and ready to fire upon a multitude in the street.”

Invisible on March 5, Adams was the center of attention the following morning when Hutchinson convened his council. He summoned as well the commanding officers of the Boston regiments; he wanted as many Crown officers in the room as possible. Across town, doctors conducted autopsies and tended to the wounded. At the Town House, Hutchinson found Boston’s selectmen waiting for him on the doorstep. Would he, they inquired, kindly remove the troops at once? Inside, several council members echoed the request. Hutchinson answered that he was without authority to order an evacuation.

From the selectmen Hutchinson learned that the town too had convened an emergency meeting. It appointed a committee, Adams at its head, to call on Hutchinson. As John Adams later drew the picture, his cousin stood late that morning before a sober, bewigged crew in scarlet cloaks and gold-laced hats. Commanding, life-size images of Charles II and James II peered over their shoulders from ornate gold frames. Hutchinson sat at the head of the table, Col. William Dalrymple, commander of the land forces, at his side. Before them Adams delivered what John considered one of the most significant speeches of the age. The gist alone survives. It was a precarious moment. Nothing would restore the town to order but the immediate removal of the troops, declared Adams. Under no circumstances, Hutchinson countered, would he order any evacuation. He regretted the events of the previous evening but had consulted with the officers of two regiments. They answered to their general in New York. Hutchinson could not countermand him. For his part, Col. Dalrymple offered to withdraw the 29th Regiment. Ultimately, Hutchinson conceded. The regiment had made itself obnoxious. It could move to the Castle, the fort in Boston Harbor, if that would appease the people. He assumed the matter closed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/50/19/5019ea36-d5e0-455d-a096-e8e0d4f9be0f/oct2022_i08_samadams.jpg)

Adams conveyed Hutchinson’s reply to the town meeting, which swelled by afternoon to 3,000 people. Packed into the pews of the Old South Church, they deemed the removal of a single regiment insufficient. Late that Tuesday, Adams made his way across Boston for a second time to remind Hutchinson that, by the Massachusetts charter, the governor—and in his absence the acting governor—assumed command of all military and naval forces within his jurisdiction. Was there to be more carnage in Boston? Adams asked. The troops, Hutchinson repeated, had their commander and their orders. He could not interfere with them. Adams warned Hutchinson of the price of his intransigence: The Massachusetts towns would descend on Boston. Ten thousand men would expel the troops if Hutchinson did not. The night ahead “would be the most terrible that had ever been seen in America.” Hutchinson reminded Adams of the definition of high treason.

With a vigorous dash of color, John Adams much later described the scene. His cousin was no orator. On great occasions, however, “when his deeper feelings were excited, he erected himself, or rather nature seemed to erect him, without the smallest symptom of affectation, into an upright dignity of figure and gesture, and gave a harmony to his voice, which made a strong impression on spectators and auditors, the more lasting for the purity, correctness and nervous elegance of his style.” March 6, 1770, was one such occasion, though the style hardly mattered. Few seemed to share his aptitude or appetite for wearing down an opponent. And no Bostonian more expertly rattled Hutchinson; it was as if decades had prepared Samuel Adams for this afternoon. “With a self-recollection, a self-possession, a self-command, a presence of mind, that was admired by every man present,” he rose. He stretched forth a trembling arm. The town had voted. No redcoat could consider himself safe in Boston, nor could any inhabitant. “If you have power to remove one regiment,” Adams enjoined Hutchinson, “you have power to remove both.” Three thousand people awaited his decision. “They are become,” added Adams, his voice sonorous, “very impatient. A thousand men are already arrived from the neighborhood, and the country is in general motion.” It was nearly dusk. An immediate answer was expected. Any bloodshed would be on the hands of Hutchinson, who should consider his life in danger.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/63/876318ef-3f24-4f0b-8749-2516cb52d952/oct2022_i06_samadams.jpg)

The language was potent, stronger than Hutchinson cared to repeat or so much as recall. It made for a spellbinding moment. Adams’ ultimatum set every pulse in the room racing. Even Dalrymple reported that Adams made him quake; he seemed more impressed by him than by the acting governor. Adams focused only on Hutchinson, “weak as water,” as unsteady as he had ever seen him. “I observed his knees to tremble,” Adams later revealed. “I thought I saw his face grow pale (and I enjoyed the sight).” He had personal reason to savor the moment but deferred to something loftier. Adams thrilled to the display of “determined citizens peremptorily demanding the redress of grievances.”

While Hutchinson seriously doubted that a mob could drive off 600 well-trained regulars, he did not care to approach that Rubicon. He recanvassed the four Crown officers in the room. They remained of the same mind. Hutchinson alone resisted a concession. It would be difficult to explain to London. He looked to Dalrymple; he preferred an officer make the decision. The previous night had been the worst Hutchinson had known in 59 years, including that on which his home had been pillaged. No one else in the room, he was reminded, believed he could deny the will of the people. Finally, Hutchinson informed Adams that he would demand Dalrymple remove both regiments. Adams’ admirers would deem the confrontation pivotal. Hutchinson emphasized its import as well, though for a different reason: Samuel Adams’ triumph, he cringed, “gave greater assurances than ever that, by firmness, the great object, exemption from all exterior power, civil or military, would finally be obtained.” In his many miserable accounts of the afternoon he rarely mentioned Adams by name, as if preferring not to put a face to his humiliation.

The streets were nearly dark when Adams returned to the Old South meeting house. A hush fell as John Hancock rose to announce his news. The room then erupted, echoing for some time with shouts and applause. The meeting also voted a night watch for the town until the troops had evacuated. For the next weeks, with muskets and cartridge boxes, a group that included John and Samuel Adams patrolled the Boston streets until dawn.

John Adams deemed his cousin’s showdown with Hutchinson worthy of Livy or Thucydides. It struck him as deserving of portraiture. The great painter John Singleton Copley caught some of its flavor when Adams sat for him later. Copley depicted Adams with the intensity on display throughout the duel. He quite literally takes a stand, ramrod straight, militant in his bearing. He is a man fortified by words. With his left index finger, he directs us to the Massachusetts charter. With his right hand he clenches the town instructions in a manner that suggests that ideas, too, deliver lethal blows. The result is a battle cry of a painting, much copied through the 1770s. Adams defends the charter like “Moses with his tablets, Luther with the Epistles,” as one historian has put it. The picture hinted that an occasional check might intrude, but that—as Hutchinson feared—“the progress of liberty would recommence.”

A week later troops still stomped about Boston. Adams prodded. Forty-eight hours had been required to land the men. Why was it taking so long to remove them? In the end, an Adams associate accompanied the redcoats to the wharf—“to protect them,” it was explained, “from the indignation of the people.” By the end of March, Boston was at last free of all redcoats save for the nine behind prison bars. Hutchinson’s brother-in-law groaned, “Thus, has an unarmed multitude in their own opinion gained a complete victory over two regiments of His Majesty’s regular troops.”

Over the next harried weeks Adams focused not on how he would be portrayed, but on how the events of March 5 would be; there is no better instance of him bracing for and improving upon events. A tragedy had relieved the town of troops. But how would the rest of the province, the other colonies, and the British Ministry react? There was much to do, in little time and for immeasurably high stakes. For starters, the evening of Monday, March 5, needed a name. Adams appears to have been the first to refer to the skirmish as a “horrid massacre,” a name that stuck. It was imperative as well to dredge from the murk a coherent narrative. Nothing about the 20 chaotic minutes had been clear, least of all to anyone in the thick of them. Soldiers had fired on and killed civilians. But had Preston—a cool-headed, popular officer with a reputation for benevolence—ever issued a command? Some distinctly heard him order his men to fire. Others swore he had not. Who had attacked whom? Had snowballs flown through the air, or had those been bricks, clubs and sticks? Were thousands of people, or 50, on hand? Witnesses reported that the first victim carried a stick. Others saw him empty-handed. There was disagreement even on the position of the moon. A sentry had been assaulted. Minutes later, three or four men lay dead. What had happened? All agreed the snow was a foot deep, the evening bright. On all other counts it was cloaked in shadow, an obscurity that Adams rushed to illuminate, both before and after the soldiers stood trial. To his dismay, all but two were exonerated. Did he really mean to suggest that—after four judges and 24 jurors had devoted weeks to the case—they were fools, and he alone could discern the truth, an antagonist challenged Adams? It seemed he did.

Adams would go on to make nearly as much trouble for historians as he did for the British. Biographers have turned him into a neurotic, a Socialist, a mobster. One profile consists solely of blistering contempt. Another whitewashes him to the point of anemia. Even when historians acknowledge his influence he disappears between the lines. “Probably no American did more than Samuel Adams to bring on the revolutionary crisis,” contended Edmund Morgan. “No one took republican values as seriously as Adams did,” writes Gordon Wood. He was “the premier leader of the revolutionary movement,” “as astute a politician as ever America has produced.” All echo Hutchinson in their claims—“the whole continent is ensnared by that Machiavelli of chaos,” Hutchinson complained—but the superlatives then slink off, headlines without articles, as if fearing the envy of John, the disapproval of Samuel, or the need to dislodge a man from behind more than 30 pseudonyms. When he does not get enough credit, he gets too much. He single-handedly directed the Stamp Act riots and the Boston Tea Party in some accounts, the Battle of Lexington in others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/dd/6cdd750f-0330-466c-8456-b1cbf022c2b4/oct2022_i03_samadams.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/98/6c98cae7-1af5-4f3b-853f-d645e5c8ed03/oct2022_i02_samadams.jpg)

Before his first inaugural address, Thomas Jefferson asked himself: “Is this exactly in the spirit of the patriarch of liberty, Samuel Adams?” Would he approve of it? To understand why the new president hoped to channel Adams’ spirit is to discover not only where a daring revolutionary came from but where a revolution did. His curious career explains how the American colonies lurched from “spotlessly loyal” to “stark, staring mad” in 15 dizzying years, how a group of drenched, pipe-smoking Massachusetts farmers, 40 miles from Boston and thousands from London, might reason that they should act sooner rather than later if they did not care to be “finessed out of their liberties.” Adams introduced them into the political system, persuading them their liberties were worth the risk of their lives. To lose sight of him is to lose sight of a man who calculated what would be required to upend an empire and who—radicalizing men, women and children, with boycotts and pickets, street theater, invented traditions, a news service, a bit of character assassination and any number of innovative, extralegal institutions—led American history’s seminal campaign of civil resistance.

Adams banked on the sage deliberations of a band of ambitious farmers reasoning their way toward rebellion. That was how democracy worked. He dreaded disunity. “Neither religion nor liberty can long subsist in the tumult of altercation, and amidst the noise and violence of faction,” he warned. He refused to believe that prejudice and private interest would ultimately trample knowledge and benevolence. Self-government was in his view inseparable from governing the self; it demanded a certain asceticism. He wrote anthem after anthem to the qualities he believed essential to a republic—austerity, integrity, selfless public service—qualities that would become more military than civilian. The contest was never for Adams less than a spiritual struggle. It is impossible with him to determine where piety ended and politics began; the watermark of Puritanism shines through everything he wrote. Faith was there from the start, as was the scrappy, iconoclastic spirit, as were the daring, disruptive excursions beyond the law.

Much of the maneuvering Adams kept out of sight while practicing it in plain view. He bobs and weaves, vanishing around corners and behind his peers. At times he amounts to little more than a flicker and dash. Even in his letters he seems to have one foot out the door. The clock strikes midnight; he cannot linger; he hates to leave us hanging—or so he says. He will tell us more, he promises, the next time.

Adapted from The Revolutionary by Stacy Schiff. Copyright © 2022. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York. All rights reserved.

Smithsonian Associates will host an evening with Stacy Schiff on Tuesday, Nov. 1 at 6:45 p.m. ET. The event will be held live at the Smithsonian’s S. Dillon Ripley Center and simulcast on Zoom. Buy your tickets here.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1761x2010:1762x2011)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/80/2b80f06e-a978-4b86-9262-f53042abbed8/sam_adams_b2.jpg)