On the Hunt for Jefferson’s Lost Books

A Library of Congress curator is on a worldwide mission to find exact copies of the books that belonged to Thomas Jefferson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Library-of-Congress-631.jpg)

For more than a decade, Mark Dimunation has led a quest to rebuild an American treasure—knowing he will likely never see the complete results of his efforts.

On an August day 195 years ago, the British burned the U.S. Capitol in the War of 1812 and by doing so, destroyed the first Library of Congress. When the war ended, former President Thomas Jefferson offered to sell his personal library, which at 6,487 books was the largest in America, to Congress for whatever price the legislators settled upon. After much partisan debate and rancor, it agreed to pay Jefferson $23,950.

Then another fire in the Capitol on Christmas Eve of 1851 incinerated some 35,000 volumes, including two-thirds of the books that had belonged to Jefferson. And although Congress appropriated funds to replace much of the Library of Congress collection, the restoration of the Jefferson library fell by the wayside.

Since 1998, Dimunation, the rare-books and special collections curator for the Library of Congress, has guided a slow-moving, yet successful search for the 4,324 Jefferson titles that were destroyed. The result of his labor thus far is on view at the library in the Jefferson Collection Exhibition.

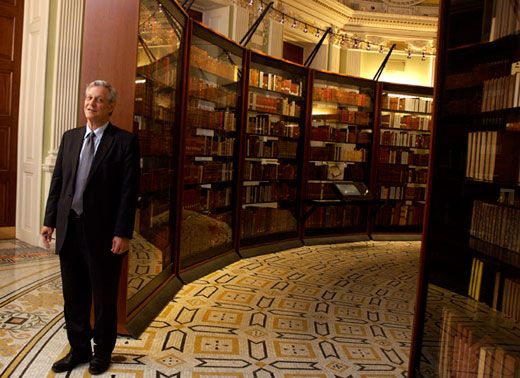

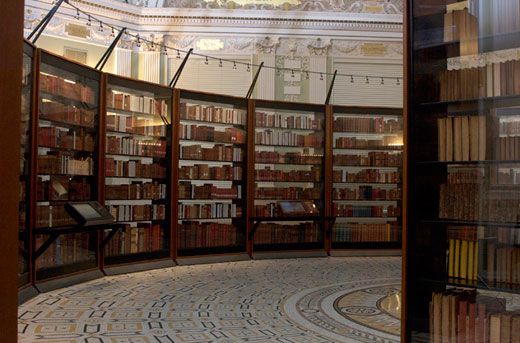

Standing in the center of the exhibit surrounded by circular shelving containing books of all shapes and subjects, visitors get a sense of the scale of Jefferson's library. Some of the spines appear wizened with age, others straight at attention. Many of the books have a green or yellow ribbon peeking out from their top. Those with a green ribbon were owned by Jefferson and those with a yellow ribbon are replacements. Books without a ribbon were taken from elsewhere in the library. "Our objective is to put on the shelf exactly the same book Jefferson would have owned. Not another edition, not the same work but printed later. The exact book that he would have owned," Dimunation says.

White boxes (297 in all) tucked in between the aged books represent missing books. "The inflow of books has slowed down right now, but it's moving at enough of a deliberate pace that it will continue," says Dimunation. "I just ordered one this week."

Make that 297 missing books.

But how did the curator and others at the Library of Congress obtain more than 4,000 18th-century books that exactly matched those owned by Jefferson? With research, patience and help from an unnamed source.

The Jefferson project, as the undertaking is called, began in 1998 with the goal of collecting as many of Jefferson's books in place as possible by the library's bicentennial in 2000. Working up to 20 hours a day, Dimunation led his team through first identifying what in the library at the time of the fire had belonged to Jefferson, what had survived and what was missing.

An essential reference in this initial stage was a 1959 five-volume catalog of Jefferson's original books compiled by Millicent Sowerby, a library employee. Not only did Sowerby note which books were Jefferson's using historical and library records, she also scoured the president's personal papers, adding annotations to the catalog every time he mentioned a work in his writings.

When the exhibit opened in 2000 after a thorough search in the library that resulted in some 3,000 matches, two-thirds of the entire collection was on display. Then, in a nod to Jefferson's methods of acquisition, Dimunation hired a rare-book dealer who had the contacts and resources to find specific things within the highly selective antique book market. This individual, who got involved because of the historic nature of the project, chooses to remain anonymous "as a gesture to the American people," says Dimunation. By using a dealer, no one knew that the Library of Congress was behind the purchases, which decreased the chances that booksellers would inflate their prices.

The mysterious dealer delivered. For eight months, boxes containing 15 to 20 books, among them a volume about horse breeding and a gardener's dictionary, arrived in regular intervals at the library. Meanwhile, Dimunation also hunted for books by calling specialized dealers and going through subject lists with them. Funding for the Jefferson project was provided by a $1 million grant from Jerry and Gene Jones, owners of the Dallas Cowboys football team.

As the library's dealer began to have less success locating books, Dimunation spent a year brainstorming a new approach, and in following years, targeted his searches by the volume's country of origin and subject. Then in 2006, he sent Dan De Simon, curator of the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection at the library and a former bookseller, to Amsterdam, Paris and London with a list of about 400 books to find. He came home with more than 100, quite a haul given the project's stagnation. It included a work by famed game-expert Edmond Hoyle about "whist, quadrille, piquet and bac-gammon."

Currently, lists of books wanted by Dimunation are circulating throughout markets in two continents. But the last 297 volumes will take time to find, and Dimunation isn't sure he will ever see them. Jefferson preferred second editions of books, because he thought first editions had errors, and "Dublin," or pirated, editions, because of their handy size. Both of these preferences make it hard to find exact matches.

In addition, some of the titles are simply obscure (such as a pamphlet on growing pomegranates), some of the listings might have mistakes, and some might not even be books, meaning they are articles or chapters submitted off printing presses before being bound. Two or three books on the list are American imprints that haven't been on the market in more than 100 years, and should they become available, the library would be in a long line to acquire them.

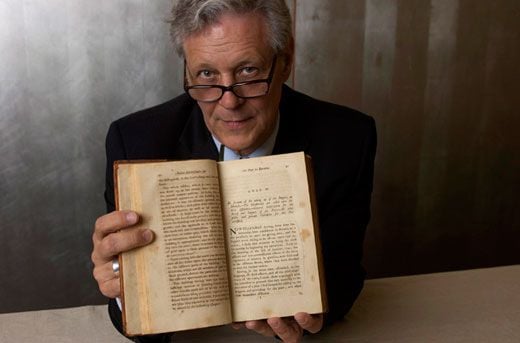

All of these challenges, however, haven't diminished Dimunation's enthusiasm for the project or his sense of humor. "There's a certain level of job security with this project," he says with a laugh, pushing his brown-rimmed glasses on to his forehead. "But those of us who are really involved in the long-term, you just become really committed to get it done. It is the foundation of the world's largest library. It's a very compelling story."

Moreover, these books aren't meant to be hallowed tomes locked behind glass. Many are still used by researchers today. Dimunation remembers a woman who requested a compilation of essays about theater during the English Restoration visiting shortly after the exhibit opened in 2000.

"I showed her how to handle the book, which is what we do in the rare-book reading room, and then I said, ‘Could you please make sure this green ribbon stays visible?' and she said, ‘Oh sure. Why, what is it?' And I said it comes from an exhibit and is Thomas Jefferson's copy," he recalls. "She threw her hands back and said, ‘I don't want to touch it.' I said she had to because it's the only copy we have!"

She sat and stared at the book for several minutes before gingerly turning the pages. "Jefferson would have loved that moment," Dimunation says. "People would travel to Jefferson to see and use his books, and here this woman is doing it almost 200 years later."