Pablo Fanque’s Fair

The showman whom John Lennon immortalized in song was a real performer—a master horseman and Britain’s first black circus owner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110908011354pablo-fanque.jpg)

Anyone who has ever listened to The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band–and that’s a few hundred million people at the last estimate–will know the swirling melody and appealingly nonsensical lyrics of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” one of the most unusual tracks on that most eclectic of albums.

For the benefit of Mr. Kite

There will be a show tonight on trampoline

The Hendersons will all be there

Late of Pablo Fanque’s Fair—what a scene

Over men and horses, hoops and garters

Lastly through a hogshead of real fire!

In this way Mr. K. will challenge the world!

But who are these people, these horsemen and acrobats and “somerset turners” of a bygone age? Those who know a bit about the history of the circus in its mid-Victorian heyday–before the coming of the music halls and the cinema stole its audience, at a time when a traveling show could set up in a mid-size town and play for two or three months without exhausting demand–will recognize that John Lennon got his vocabulary right when he wrote those lyrics. “Garters” are banners stretched between poles aloft held by two men; the “trampoline,” in those days, was simply a springboard, and the “somersets” Mr. Henderson undertakes to “throw on solid ground” were somersaults.

While true Beatlemaniacs will know that Mr. Kite and his companions were real performers in a real troupe, however, few will realize that they were associates of what was probably the most successful, and almost certainly the most beloved, “fair” to tour Britain in the mid-Victorian period. And almost none will know that Pablo Fanque–the man who owned the circus—was more than simply an exceptional showman and perhaps the finest horsemen of his day. He was also a black man making his way in an almost uniformly white society, and doing it so successfully that he played to mostly capacity houses for the best part of 30 years.

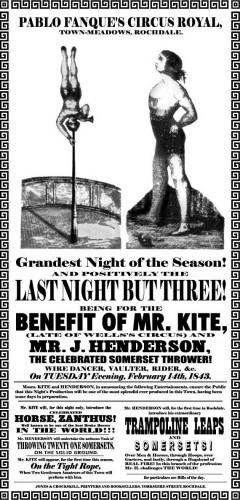

The 1843 benefit poster advertising a performance in Rochdale by Pablo Fanque's circus. It was this bill that John Lennon discovered in a Kent antique shop and used as inspiration for his song "Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite."

The song that lent Fanque his posthumous fame had its origins in a promotional film shot for “Strawberry Fields Forever”—another Lennon track—at Sevenoaks in Kent in January 1967. During a break in the filming, the Beatle wandered into a nearby antique shop, where his attention was caught by a gaudy Victorian playbill advertising a performance of Pablo Fanque’s Circus Royal in the northern factory town of Rochdale in February 1843. One by one, in the gorgeously prolix style of the time, the poster ran through the wonders that would be on display, among them “Mr. Henderson, the celebrated somerset thrower, wire dancer, vaulter, rider &c.” and Zanthus, “well known to be one of the best Broke Horses in the world!!!”—not to mention Mr. Kite himself, pictured balancing on his head atop a pole while playing the trumpet.

Something about the poster caught Lennon’s fancy; knowing his dry sense of humor, it was probably the bill’s breathless assertion that this show of shows would be “positively the last night but three!” of the circus’s engagement in the town. Anyway, he bought it, took it home and (the musicologist Ian MacDonald notes) hung it in his music room, where “playing his piano, sang phrases from it until he had a song.” The upshot was a track unlike any other in the Beatles’ canon—though it’s fair to say that the finished article owes just as much to the group’s producer, George Martin, who responded heroically to Lennon’s demand for “a ‘fairground’ production wherein one could smell the sawdust.” (Adds MacDonald, wryly: “While not in the narrowest sense a musical specification, was, by Lennon’s standards, a clear and reasonable request. He once asked Martin to make one of his songs sound like an orange.”) The Abbey Road production team used a harmonium and wobbly tapes of vintage Victorian calliopes to create the song’s famously kaleidoscopic wash of sound.

What the millions who listened to the track never knew was that Lennon’s poster caught Pablo Fanque almost exactly midway through a 50-year career that brought with it some remarkable highs and astonishing lows, all of them made a little more exceptional by the unpromising circumstances of his birth. Parish records show that Fanque was born William Darby in 1796, and grew up in the English east coast port of Norwich, the son of a black father and a white mother. Nothing certain is known about Darby senior; it has been suggested he was born in Africa and came to Norwich as a household servant, even that he may have been a freed slave, but that is merely speculation. And while most sources suggest that he and his wife died not long after their son’s birth, at least one newspaper account has the father appearing in London with the son as late as the mid-1830s. Nor do we know exactly how “Young Darby” (as he was known for the first 15 or 20 years of his circus career) came to be apprenticed to William Batty, the proprietor of a small traveling circus, around 1810, or why he chose “Pablo Fanque” as his stage name.

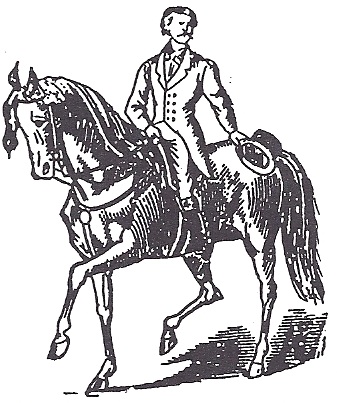

Andrew Ducrow rides five-in-hand during a performance of "Mazeppa", an elaborately staged spectacle, loosely based on the life of the Cossack chief, that helped make his name.

What we can say is that Fanque proved to be a prodigy. He picked up numerous acrobatic skills (he was billed at various stages of his career as an acrobat and tightrope walker) and became renowned as the best horse trainer of his day. The latter talent was most likely developed during a spell with Andrew Ducrow, one of the most prestigious names in the history of the circus and a man sometimes considered the “greatest equestrian performer who has ever appeared before the public.” By the mid-1830s, Fanque was noted not only as a daringly acrobatic master of the corde volante, but also as a superb horseman, billed in the press as “the loftiest jumper in England.”

His most remarkable feat, according to the circus historian George Speight, was leaping on horseback over a coach “placed lengthways with a pair of horses in the shafts, and through a military drum at the same time,” and during the 1840s, the Illustrated London News reported, “by his own industry and talent, he got together as fine a stud of horses and ponies as any in England,” at least one of which was purchased from Queen Victoria’s stables. Fanque was capable of turning out horses that “danced” along to well-known tunes, and it was said that “the band has not to accommodate itself to the action of the horse, as in previous performances of this kind.”

John Turner, who has researched Fanque’s life more thoroughly than any other writer, says that he found little or no evidence that Fanque suffered racial discrimination during his long career. Contemporary newspapers mention his color infrequently, and incidentally, and many paid warm tribute to his charity work; the Blackburn Standard wrote that, in a world not often noted for plain dealing, “such is Mr. Pablo Fanque’s character for probity and respectability, that wherever he has been once he can go again; aye, and receive the countenance and support of the wise and virtuous of all classes of society.” After Fanque’s death, the chaplain of the Showman’s Guild remarked: “In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line, for, although Pablo was of African extraction, he speedily made his way to the top of his profession. The camaraderie of the Ring has but one test, ability.”

Yet while all this may be true—there’s plenty of evidence, in late Victorian show-business memoirs, that Fanque was a well-respected member of an often disrespected profession—racism was pervasive in the nineteenth century. William Wallett, one of the great clowns of the mid-Victorian age, a friend of Fanque’s who worked with him on several occasions, recalls in his memoirs that on one visit to Oxford, “Pablo, a very expert angler, would usually catch as many fish as five or six of us within sight of him put together”—and this, Wallett adds, “suggested a curious device” to one irked Oxford student:

One of the Oxonians, with more love for angling than skill, thought there must be something captivating in the complexion of Pablo. He resolved to try. One morning, going down to the river an hour or two earlier than usual, we were astonished to find the experimental philosophical angler with his face blacked after the most approved style of the Christy Minstrels.

The acrobat and equestrian John Henderson as owner of his own circus in the 1860s, from a contemporary circus poster.

Although Wallett does not say so, the gesture was a calculated insult, and it may also be significant that it took Fanque years to gather up the wherewithal to go into business for himself. He did not own his circus until 1841, three decades into his career, and when he did finally leave Batty it was with just two horses and a motley assortment of acts, all of them provided by a single family: a clown, “Mr. R. Hemmings and his dog, Hector,” together with “Master H. Hemmings on the tightrope and Mr. E. Hemmings’ feats of balancing.’ ”

Still, Fanque’s showmanship, and a reputation for treating his acts well, helped him to expand his troupe. We have already seen that he was joined by William Kite, the acrobat, and John Henderson, well-known as a rider, wire-walker and tumbler, in Rochdale in 1843. By the middle of the century, historian Brian Lewis notes, Fanque’s circus had become a fixture in the north of England, so it seemed entirely natural for the schoolchildren of one mill town to celebrate a holiday with “a tour of a bazaar … refreshments and a visit to Pablo Fanque’s circus.” The troupe grew to include a stable of 30 horses; clowns; a ring master, Mr. Hulse; a band, and even its own “architect”–a Mr. Arnold, who was charged with erecting the wooden “amphitheatres” in which they generally performed. When the circus rolled into the Lancashire town of Bolton in March 1846, Fanque himself announced its coming by driving through the main streets twelve-in-hand, a spectacular feat of horsemanship that brought considerable publicity. There were many extended seasons in locations throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. At one point, the circus was based in its own purpose-built auditorium in Manchester, capable of holding an audience of 3,000.

One reason for Fanque’s success that goes unremarked in the circus histories is his keen appreciation of the importance of advertising. Among the advantages that his circus enjoyed over its numerous rivals was that it enjoyed the services of Edward Sheldon, a pioneer in the art of billposting whose family would go on to build the biggest advertising business in Britain by 1900. Fanque seems to have been among the first to recognize Sheldon’s genius, hiring him when he was just 17. Sheldon spent the next three years as Pablo’s advance man, advertising the imminent arrival of the circus as it moved from town to town. Several other mentions of Fanque also testify to his talent for self-promotion. In Dublin in 1851 (and perhaps not entirely inadvertently), another of his stunts prompted a virtual riot. The Musical World reported:

The Dublin playgoers … have nearly torn down a theatre, because of a shockingly bad riddle. “Pablo Fanque, the acrobat,” advertised the gift of a pony and car to the propounder of the best riddle. There were 1,056 competitors, and the prize was awarded to Miss Emma Stanley, for a conundrum so mediocre, that we will not attempt to transcribe it; it is neither good enough nor bad enough for notice. The audience, touched with a sense of national degradation, that out of more than a thousand Irish, not one could make a better piece of wit, broke into such excesses, that a body of police had to be marched into the building, to preserve it from wreck.

Emily Jane Wells, the teenage equestrienne, performed alongside Fanque's circus c.1860 in a benefit for her father, John. She was "regarded as the most finished and graceful" of British circus horsewomen.

The lineup of performers in Fanque’s circus varied endlessly. At one point, Pablo traveled with Jem Mace, the celebrated bare-knuckle boxing champion, who put on exhibitions of fisticuffs, while toward the end of his career he employed a “Master General Tom Thumb”—a play on Barnum’s famous midget—and Elizabeth Sylvester, Britain’s first female clown. He also exploited the provocative allure of “Miss Emily Jane Wells,” whose “pleasing Act of Horsemanship” was daringly performed in “Full Bloomer Costume!!” Late in life, Fanque switched to an entirely family-oriented show, recognizing that it would appeal to a broader range of customers. Bringing in a more middle-class audience allowed Fanque to charge the then-high price of a shilling for a box seat and sixpence for the pit.

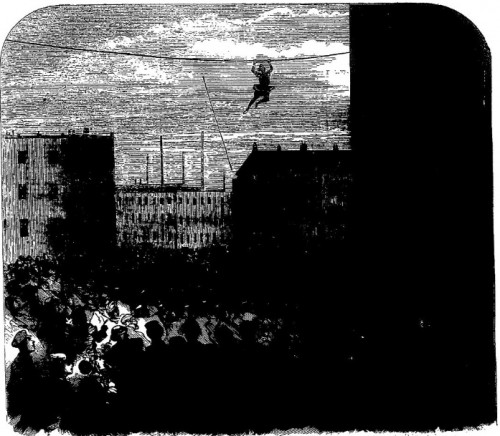

For most of these years, Fanque remained respected and esteemed, a fixture on the northern touring circuit, while attaining national prominence just once, when, in Bolton in May 1869, his decision to hire another female performer, “Madame Caroline,” (billed as “the Female Blondin” in imitation of the world-famous tightrope walker and conqueror of the Niagara Falls), almost resulted in tragedy. As the “wire dancer” set off on a rope strung between two buildings in one of the town’s busiest streets, the Penny Illustrated Paper reported, she

stumbled, threw away the balance pole, but by a desperate effort grabbed the rope. She made strenuous efforts to regain her position, but although a strong muscular woman, she was unable to do so and remained suspended in mid-air. Loud cries then arose from the crowd… Attempts were made to lower the rope, which was at a height of about 30 feet, but these were unsuccessful. Just as the poor woman was becoming exhausted, men’s jackets were piled below her and she was persuaded to drop into the arms of those beneath … sustaining no injury beyond the fright and a shake.

Yet Pablo’s life was not without its tragedies. The circus was a harsh mistress. Wallett’s memoirs are filled with gleeful accounts of “triumphs” interspersed with almost equally numerous descriptions of the “chequered fortunes” that saw the circus play to tiny crowds, in bitter weather, or lose out to the more compelling spectacles offered by competing shows. Members of the profession lived on the cusp of financial disaster; the Law Times of December 1859 contains the record of a successful action that Fanque brought against a bankrupt performer to whom he had lent “a number of horses and theatrical accessories,” while he was forced on at least one occasion to close down his circus and sell most of his horses, retaining just enough “to preserve the nucleus.” (On this occasion, Turner notes, “short of resources, Pablo is reported to have appeared at William Cooke’s circus, on the tight-rope.”) On another occasion, Fanque found his troupe sold from under him when a creditor transferred Fanque’s debts to his old master, William Batty, who—Wallett recorded–”came down, holding a bill of sale, and in a most wanton and unfeeling manner sold up the whole concern.”

The lowest point of Fanque’s career, however, came on March 18, 1848, when his circus was playing in Leeds. The troupe took over a wooden amphitheatre that had been erected for his rival Charles Hengler, and used it to put on a benefit performance for Wallett. Partway through the show, when the pit was packed with an audience estimated at well over 600, some supports gave way and the floor collapsed, pitching the spectators down into the lower gallery used for selling tickets. Fanque’s wife, Susannah—the daughter of a Birmingham button-maker and mother to several children who also performed with the circus—was in the ticket booth, and happened to be leaning forward when the structure, according to the Annals and History of Leeds:

fell with a tremendous crash, precipitating a great number of people into the gallery… Mrs Darby and Mrs Wallett were… were both knocked down by the falling timber; two heavy planks fell upon the back part of the head and neck of Mrs Darby, and killed her on the spot. Mrs Wallett, besides a many others, received bruises and contusions, but the above was the only fatal accident.

Fanque rushed to the scene, helped to move the heavy timbers, and carried his wife in his arms to a nearby tavern; a surgeon was called for, but there was nothing to be done. A few days later Susannah “was interred at the Woodhouse cemetery, where a monument records the melancholy event.” At the inquest into her death, it emerged that the builder’s men had partially dismantled the amphitheatre before Fanque arrived, removing a number of the supporting beams, and the structure had been sold to him “as it stood,” with the new owner undertaking “to make any alterations as he liked at his own expense.” Although Pablo still employed Arnold, the architect, nothing was apparently done to strengthen to flooring, but no charges were ever brought against either man for negligence. To make matters worse, it was discovered that as Mrs. Darby lay dead amid the pandemonium, the box containing the evening’s takings, amounting to more than £50, had been stolen.

After his wife’s death, Fanque married Elizabeth Corker of Sheffield, who was 20 years younger than he. They had several children, all of whom joined their circus, and one of whom, known professionally as Ted Pablo, once performed before Queen Victoria and lived into the 1930s.

As for Fanque himself, he survived just long enough to witness the beginnings of the circus’s terminal decline. He died, aged 76 and “in great poverty” (so the equestrian manager Charles Montague recalled in 1881), in a rented room in a Stockport inn.

He was remembered fondly, though. A vast crowd lined the route of his funeral procession in Leeds in May 1871. He was buried alongside his first wife.

Sources

Anon. “Irish war.” The Musical World, 19 April 1851; Anon. “Hope and another v Batty,” The Law Times, November 19, 1859; Brenda Assael. The Circus and Victorian Society. Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2005; Thomas Frost. Circus Life and Circus Celebrities. London: Chatto and Windus, 1881; Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (ed). Black Victorians/Black Victoriana. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2003; Brian Lewis. The Middlemost and the Milltowns: Bourgeois Culture and Politics in Early Industrial England. Stanford : Standford University Press, 2001; Ian MacDonald. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico, 1994; John Mayhall. Annals and History of Leeds and Other Places in the County of York. Leeds: Joseph Johnson, 1860; Henry Downes Miles. Pugilistica: the history of British boxing containing lives of the most celebrated pugilists… London: J. Grant 1902; Cyril Sheldon. A History of Poster Advertising. London: Chapman and Hall, 1937; John Turner. ‘Pablo Fanque’. In King Pole, December 1990 & March 1991; John Turner. The Victorian Arena: The Performers; A Dictionary of British Circus Biography. Formby, Lancashire: Lingdales Press, 1995; W.F. Wallett. The Public Life of W.F. Wallett, the Queen’s Jester. London: Bemrose & Sons, 1870.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)