Pay No Attention to the Spies on the 23rd Floor

For years, the KGB secretly spied on visitors to the Hotel Viru in Estonia. A new museum reveals the fascinating time capsule and all the secrets within

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/KGB-Hotel-Estonia-Collage-631.jpg)

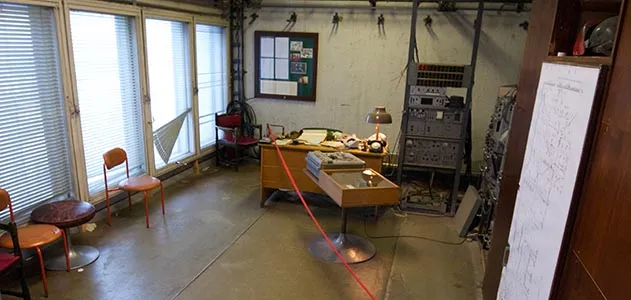

The radio room on the top floor of the Hotel Viru in Tallinn, Estonia hasn’t been touched since the last KGB agent to leave turned out the lights in 1991. A sign stenciled on the door outside reads “Zdes' Nichevo Nyet”: There Is Nothing Here.

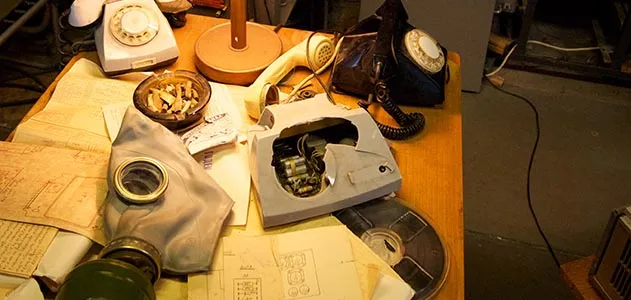

The floor inside is yellowed linoleum. A cheap orange typewriter still has a sheet of paper in it; sheets filled with typed notes spill off the table and onto the floor. The dial of a light-blue telephone on the particleboard desk has been smashed. There’s a discarded gas mask on the desk and an olive-green cot in the corner. The ashtray is full of cigarette butts, stubbed out by nervous fingers more than 20 years ago. Mysterious schematics labeled in Cyrillic hang on the wall, next to steel racks of ruined radio equipment.

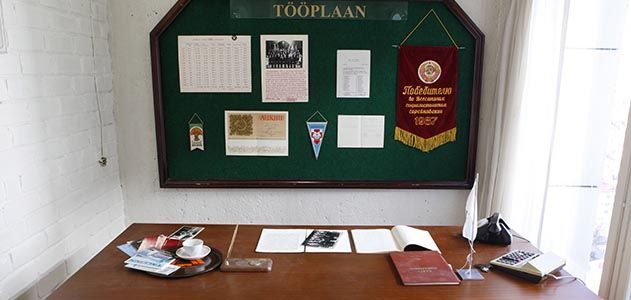

The Hotel Viru’s unmarked top floor, just above the restaurant, belonged to the Soviet secret police. At the height of the Cold War, this room was manned by KGB agents busy listening in on hotel guests. The air here is thick with untold stories. Today, an unlikely museum to Estonia’s Soviet past tries to tell some of them. Guided tours leave the hotel lobby several times a day, traveling up 23 floors and 22 years back in time.

The hotel, a glass and concrete block that towers over the capital’s historic city center, opened in the early 1970s an ambitious bid to attract tourist dollars from Finland and Western Europe. Yet on an August night in 1991, perhaps spooked by the imminent collapse of the Soviet Union, the hotel’s behind-the-scenes overseers simply vanished. Hotel employees waited for weeks before finally creeping up to the dreaded 23rd floor. There they found signs of a hasty departure: Smashed electronics, scattered papers and overflowing ashtrays. Bulky radio equipment was still bolted to the concrete walls.

A few years later, the Viru was privatized and purchased by the Finnish Sokos Hotels chain. With remarkable foresight, the new owners left the top floor untouched when they remodeled the building, sealing it off for more than 20 years. “As an Estonian, at the beginning of the ‘90s you wanted to get away from the Soviet past as fast as possible,” says Peep Ehasalu, the Viru’s communications director. “The Finns could look at it with some more perspective.”

Tiny Estonia – today there are just 1.5 million people in the whole country -- was absorbed into the USSR after WWII.

After the Iron Curtain descended, Estonia had virtually no contact with the outside world. In the 1960s, Tallinn got just a few hundred foreign visitors a year. “Billions of dollars in tourism were just passing the Soviet Union by,” says tour guide Kristi Jagodin. “The bosses in Moscow thought maybe re-opening a ferry line to Finland would be a way to get their hands on some of that hard currency.”

Not long after ferry service began, Estonia found itself flooded with 15,000 tourists a year, mostly Finns and homesick Estonian exiles. For the Soviets, this was both a crisis and an opportunity: Foreigners brought in much-needed hard currency, but they also brought in ideas that threatened the socialist order.

The solution: A brand-new hotel, wired for sound. The KGB, Ehasalu says, was interested above all in Estonians living in the West, who might sow dissent among their countrymen in the Soviet Union and were immune to Soviet propaganda. Sixty guest rooms were bugged, with listening devices and peepholes concealed in the walls, phones and flowerpots. In the hotel restaurant, heavy-bottomed ashtrays and bread plates held yet more listening devices. Sensitive antennae on the roof could pick up radio signals from Helsinki, 50 miles away across the Baltic Sea, or from ships passing by the Estonian coast.

Even the walls of the sauna – a typical place for visiting Finns to discuss business – were bugged. Businessmen discussing contracts in the hotel often found their negotiating partners the next day unusually well-informed about their plans. “It’s hard to explain today,” Ehasalu says. “If the whole country is paranoid, then everything and everybody is dangerous.”

Foreign journalists were also a target – the KGB wanted to know who they were talking to in Tallinn and what they might write about the USSR when they went home.

The Soviets imported Finnish workers to make sure the building was completed on time and measured up to Western standards. When it opened in 1972, life inside was virtually unrecognizable to everyday Estonians. The restaurant always had food on the menu; there was a racy cabaret and even a recording studio that doubled as a way to pirate cassettes brought in by Finnish sailors and tourists. “The hotel was a propaganda tool,” Jagodin says. “Everything was provided in the hotel so guests wouldn’t have to leave.”

When the hotel installed its first fax machine, in 1989, the operator traveled to Moscow for two weeks of training. Any incoming fax was copied twice – once for the recipient, once for the KGB. Sakari Nupponen, a Finnish journalist who visited Estonia regularly in the 1980s and wrote a book about the hotel, remembers the desk clerk scolding him for buying bus tickets: “’Why are you leaving the hotel so much?’ she wanted to know.”

Behind the scenes, the hotel was a mirror image of a Western business. It was wildly inefficient, with 1080 employees serving 829 guests. Maids were picked for their lack of language skills, so as to prevent unauthorized chit-chat. The kitchen staff tripled: One employee put portions on the plate, and two weighed the meals to make sure nothing had been skimmed off the top. The dark-paneled bar on the second floor was the only place in Estonia that served Western alcohol brands – and only accepted dollars, which were illegal for Soviet citizens to possess.

People in Tallinn still have strong feelings about the Soviet past. “It’s not ancient Rome,” says Ehasalu. “It was 20 years ago.” While teenagers visiting the museum are surprised by tales of life in Tallinn before they were born, their parents have complex, often conflicting memories of their decades as unwilling parts of the USSR.

The museum has to tread carefully to avoid putting too lighthearted a spin on history while acknowledging the dark humor people still find in the Soviet past. “There’s nostalgia, for sure. People were young in those days, and they have good memories. Other people were tortured and suffered under the KGB,” Ehasalu says. “We want to show that people lived two parallel lives. There was life, and on the other hand this over-regulated and absurd world around them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)