A Photographic Chronicle of America’s Working Poor

Smithsonian journeyed from Maine to California to update a landmark study of American life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/54/8d544b4f-9623-46cb-831c-5a047dd7c770/dec2016_g04_letusnowpraisefamousmen.jpg)

Just north of Sacramento is a tiny settlement that residents call La Tijera, The Scissors, because two roads come together there at a sharp angle. On the dusty triangle of ground between the blades sit more than a dozen dwellings: trailers, flimsy clapboard cabins, micro duplexes. A mattress under a mulberry tree lies amid broken-down cars and other castoffs. Roosters crow. Traffic roars past. Heat ripples off the pavement, a reminder of California’s epic drought.

Martha, 51, emerges from one of the tiny duplexes to greet me and Juanita Ontiveros, a farmworker organizer, who’d telephoned ahead. Martha’s hair is slicked back and she wears freshly applied eye shadow. Yet she looks weary. I ask her about work. Martha replies in a mixture of Spanish and English that she will soon begin a stint in a watermelon-packing plant. The job will last two months, for $10.50 an hour.

After that?

“Nothing.”

Her husband, Arturo, does irrigation labor for $9 per hour. The state minimum wage is $10. “They won’t pay more than $9,” she says. “‘You don’t want it? Eh. Plenty of other people will take the job.’ ” Adding to their woes, his job is seasonal, and after several months he’s laid off, a problem faced by about a million farmworkers, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Martha, originally from Tijuana, and Arturo, from Mexicali, are undocumented workers who have been in the United States most of their lives. (Martha came at age 8.) They are three months behind on the $460 rent. “Maybe I’ll marry Donald Trump,” she says, deadpan, then laughs. “I volunteer at the church. I bag food for families.” Because she volunteers, the church gives her extra food. “So I share,” she says of the goods she passes along to neighbors. “Helping people, God helps you more.”

I went to The Scissors, driving by vast walnut groves and endless fields of safflower, tomatoes and rice, to report on a particular kind of poverty in the country right now, and I did so with an amazing, strange American artwork in mind. It was 75 years ago that the writer James Agee and the photographer Walker Evans published the most lyrical chronicle of the lives of poor Americans ever produced, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and to consider even briefly some of the notions raised in that landmark book seemed a useful thing to do, and a necessary one in this age of widening income disparity.

Agee moved in with cotton sharecroppers in rural, Depression-scarred Alabama in the summer of 1936. Though their project started out as a Fortune assignment (which the magazine never published), in the end it flouted all journalistic constraints and appeared as a 470-page book, a potent combination of Evans’ indelible black-and-white pictures and Agee’s operatic prose. Their effort, Agee wrote, was to undertake “an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.” The book tanked, despite its startling originality—“the most realistic and the most important moral effort of our American generation,” the critic Lionel Trilling wrote in 1942. Then, in the 1960s, as Agee’s reputation grew (his posthumous novel A Death in the Family won the 1958 Pulitzer Prize) and there was renewed interest in America’s poverty problem, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men experienced a rebirth, and is now admired as a classic of literary reportage.

Thirty years ago, I went to Alabama with the photographer Michael S. Williamson to follow up on the people described by Agee and Evans. We met with 128 survivors or descendants, and in 1989 published a book, And Their Children After Them. It was, I wrote then, “about a group of men and women who long ago told us something about America that we, as a society, do not readily want to face, and who today have something else to tell us about ourselves.”

To mark the 75th anniversary of the Agee-Evans enterprise, the photographer Matt Black and I traveled to California’s Central Valley, Cleveland and northern Maine—places that, in their own ways, are close to the bottom of the nation’s stratified economy. Like Agee and Evans, we generally focused on people who can be described as the working poor.

The official U.S. poverty level is an annual income below $11,880 for a single person or $24,300 for a household of four. That yields a rate of 13.5 percent of the population, or 43.1 million people, according to the U.S. Census. But because these figures don’t fully account for the skyrocketing cost of housing, among other things, they underestimate the number of Americans enduring hard times. “Low income”—which I take as synonymous with “working poor”—is $23,760 for a single person, $48,600 for a four-person household. At that cutoff, 31.7 percent of the population is seriously struggling. That’s 101 million Americans.

Undoubtedly the economic story of our time is the growing income gap: Between 2009 and 2015, the top 1 percent nabbed 52 percent of the income gains in the so-called recovery, according to Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. I found ample evidence for the troubling decline in what experts call the “labor share” of revenue, the amount devoted to workers’ pay rather than executive salaries and corporate profits.

But I encountered something else that Agee didn’t find 75 years ago and that I didn’t find even 30 years ago. It came from a former drug dealer in Cleveland who is now taking part in a kind of economic experiment. It was a word I haven’t heard in decades of reporting on poverty: “hope.”

**********

California’s Central Valley covers some 20,000 square miles, an area larger than nine different states. Some 250 different crops are grown, one-quarter of America’s food: 2 billion pounds of shelled nuts annually, for example, 30 billion pounds of tomatoes. Near the edges of the farms and orchards, the illusion of an eternal flat plain is broken only by glimpses of the persimmon-colored Coast Ranges or the Sierra foothills.

The official poverty rate in the valley is stunning: one in five residents in many of its counties. In Fresno, the third-poorest U.S. city with a population over 250,000, one out of three residents lives below the poverty line, and of course far more than that qualify as “working poor.” Certainly the seasonal nature of farm work has always been part of the struggle. But life is also growing harder for farmworkers because of increasing mechanization, according to Juanita Ontiveros, a veteran activist, who marched with Cesar Chavez in the 1960s. It has long been an American contradiction that those who grow our food often go hungry. You can see the desperation in the drawn faces of farmworkers walking along the roads, feel it when passing countless dusty settlements like The Scissors.

In Cantua Creek, 200 miles south of Sacramento, a taco wagon was parked at a crossroads across from a cotton field. The talk there, as it was everywhere I went in the valley, was about the cutbacks in planting and harvesting brought on by the drought, now in its sixth year. Maribel Aguiniga, the owner, said business was down. “People are like the squirrels,” she said. “They save up to get ready for winter.”

I thought about the poverty that Agee saw in 1936, when Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal gave many poor Americans a lift. In fact, the three Alabama families documented by Agee at first assumed that he and Evans were New Deal agents who had arrived to help. Government was seen by many as a savior. Fifty years later, when I followed in Agee’s footsteps, the mood in the country had changed, as epitomized by President Ronald Reagan’s statement that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” The government certainly wasn’t involved in the lives of the 128 people we met connected to the Agee-Evans book. None was on welfare. They were on their own, working in tough jobs for low pay.

What I found in my travels this year is a stark contrast to the top-down approach of the 1930s and the go-it-alone 1980s. This time the energy is coming not from the federal government but from city governments, local philanthropies and a new generation of nonprofit organizations and for-profit businesses with social missions.

In the town of Parksdale, at a freshly leveled former vineyard, ten families, most who work in agriculture, were helping each other build homes through Self-Help Enterprises Inc., a nonprofit in Visalia that cobbles low-interest loans with federal and state funding. Since 1965, it has created nearly 6,200 homes in the region. Instead of a down payment, participants put in sweat equity, doing some 65 percent of the labor. Each family must contribute 40 hours per week over the roughly one-year construction period.

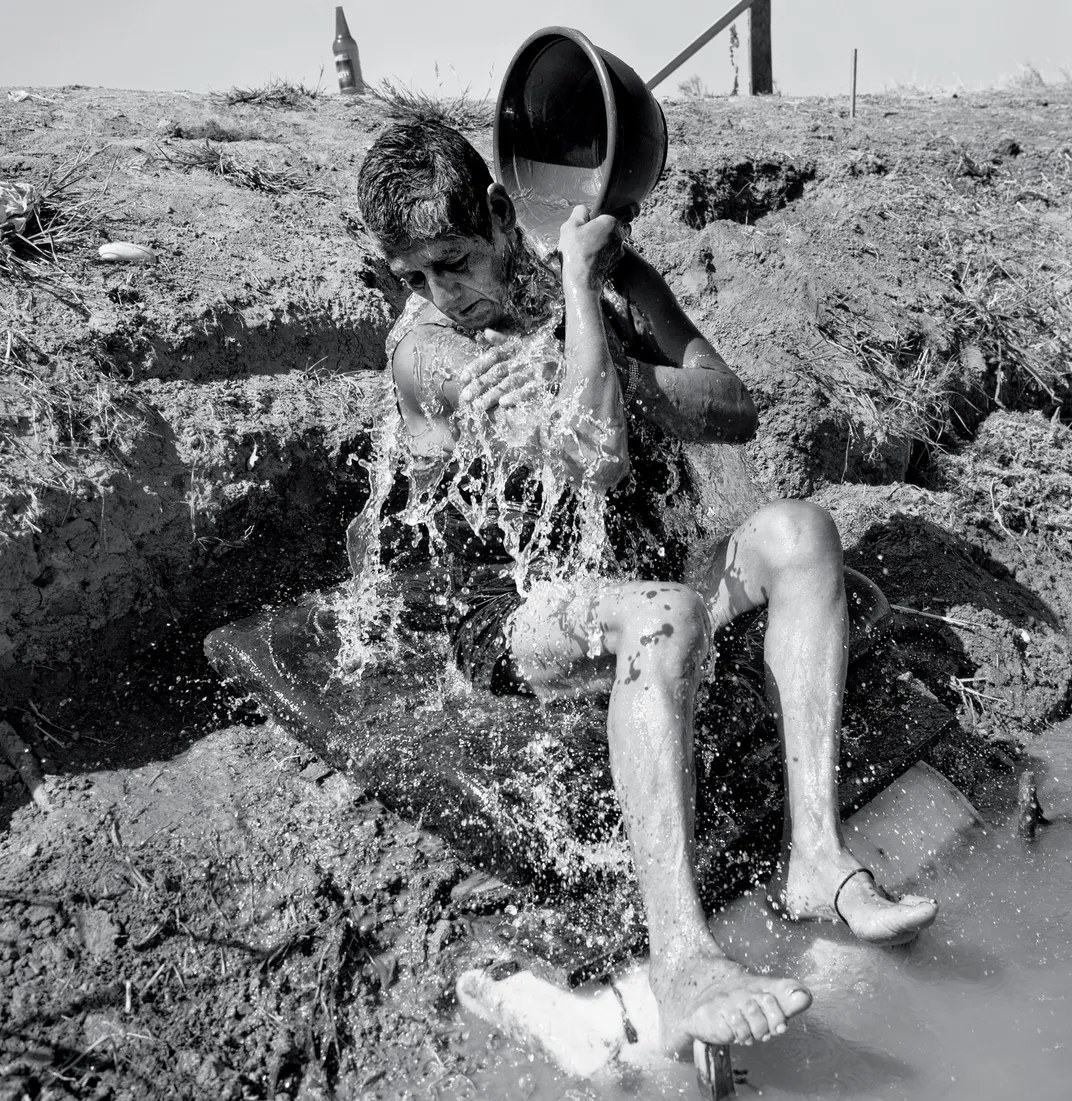

I volunteered for three days. On the first, I took turns with Albino Rameriz, 43, operating a 70-pound Makita jackhammer to chisel holes into the concrete-like “soil.” The sun burned down. It was 103 degrees. Rameriz outworked me. Though he stands just over five feet, he whipped the jackhammer around. On a break, he held up his hands.

“I’ve got blisters,” he said in Spanish, showing me his fingers. “It’s a sign that we’re working. If you want a little, you get a little. If you want more, you work for it.”

Amazingly, he’d already put in a shift harvesting tomatoes before coming here. Green stains marked his pants. His fingernails were black at the quicks from the acid in the jugo de tomate. I was further amazed that the house isn’t for him. He was donating hours to help a friend.

I was interested in getting to know Simon Salazar, 40, who was building with his wife, Luz, 42, and their three children. His family now lives in a three-bedroom house that faces the Highway 99 freeway and its constant thunder of passing cars and big rigs. His rent, which is subsidized by the county, is $1,300. They’ll move into a four-bedroom house on this quiet cul-de-sac. The mortgage: $720.

The group got to talking about the cost of living. “I don’t think you struggle like us,” Salazar said to me. This wasn’t as dismissive as it might appear in print. It was an honest observation. I felt the economic divide between us. Salazar, who was born in nearby Madera, had wanted to take part in this program in 2015, but he earned too little, less than $20,000, to qualify. This year, because his job as a mechanic in a raisin-processing plant went full time, he cracked $30,000. He was working 12-hour shifts during the grape harvest.

On the second day, I helped wire together steel rebar in foundation forms. I asked Salazar: “Do you consider yourself poor?” He paused. Rubbed his beard. He pointed to a white 2005 Honda Odyssey parked on the street. He saved two years before buying the used minivan with cash. He said that some people might appear to be rich, but are they really wealthy if they owe money on most of their possessions?

“There are a lot of rich people that are just like us. They have nothing. Everything’s in debt.” Except for his rent or mortgage, he said, “Everything is mine. No debt to nobody. It’s better to be healthy than to have money. We’re trying to make our house. To have something for the kids. For us when we get old. I’m poor. It’s OK. For me it’s very rich having a house.”

**********

In northern Maine, one out of five residents falls below the poverty line. Maine is the whitest state in the union, at 94.9 percent. The median age is 44, tied for oldest. Paper mills, once a key source of jobs, have shuttered all over, but the Millinocket area was especially hit hard by the closing in the last eight years of two mills owned by the Great Northern Paper Company. At their peak the mills employed more than 4,000 people.

Roaming downtown Millinocket, with its many vacant storefronts, I found a song lyric scrawled on an abandoned building:

I hold

My own

death as a

card in the

deckto be played

when there

are no

other cards

left

A few blocks south was a vine-covered chain-link fence. Behind it were the ruins of the mill that closed in 2008. Nearby, an insurance adjuster was measuring a run-down house. I asked him what people do for work. He said he felt lucky to have a job. His neighbors? “Up here, they’re starving. Kids in high school, the first thing they want to do is get out.”

I came across two young men, seemingly in their late teens, carrying fishing poles and a canoe, which they were about to put into the river flowing past the dead mill. I asked what people here do, meaning, for work. “Drugs,” one answered, “because there’s nothing to do.” In fact, Maine is on a course to reach nearly 400 drug overdose deaths this year, the majority involving heroin—a 40 percent increase over 2015, according to the state attorney general’s office. While well-off people also use heroin, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control says the majority of deaths in Maine are taking place in the poorest counties.

In the coastal city of Machias, there’s a tradition of seasonal jobs: hand-raking blueberries; “tipping,” or cutting, fir branches for holiday wreaths; fishing. But blueberry fields are increasingly being mechanically picked. Fishing is vastly diminished because of overharvesting.

Katie Lee, 26, is a single mother of three, and her life on this stony coast is grist for a country and western song: pregnant at 15, lived in a tent for a while, survived on meager welfare. Now she has an $11.70 per hour job at a care home and puts in endless hours. Each time solvency nears, though, an unexpected bill hits. When we met, her car had just broken down and she faced a $550 repair. It might as well have been $55,000.

She dreams of better pay and was about to start taking college classes through a program with Family Futures Downeast, a nonprofit community organization. She’d also like to be a role model for her children. “I want to teach the kids that I never gave up,” Lee said of her college ambition. Her eyes were heavy—she’d been up for 26 hours straight because of a long shift and her children. “I’m hoping by next year that I’m going to be able to save and not live paycheck to paycheck.”

Farther north, at a cove off the Bay of Fundy some four miles from the Canadian border, the tide was out, exposing vast mud flats dotted with a few tiny specks. The specks began to move—people who dig steamer clams for a living. I donned rubber boots lent to me by Tim Sheehan, the owner of Gulf of Maine Inc., which buys from the clammers. “There’s no other real work left here for someone without an education,” Sheehan told me. Top diggers earn as much as $20,000 per year.

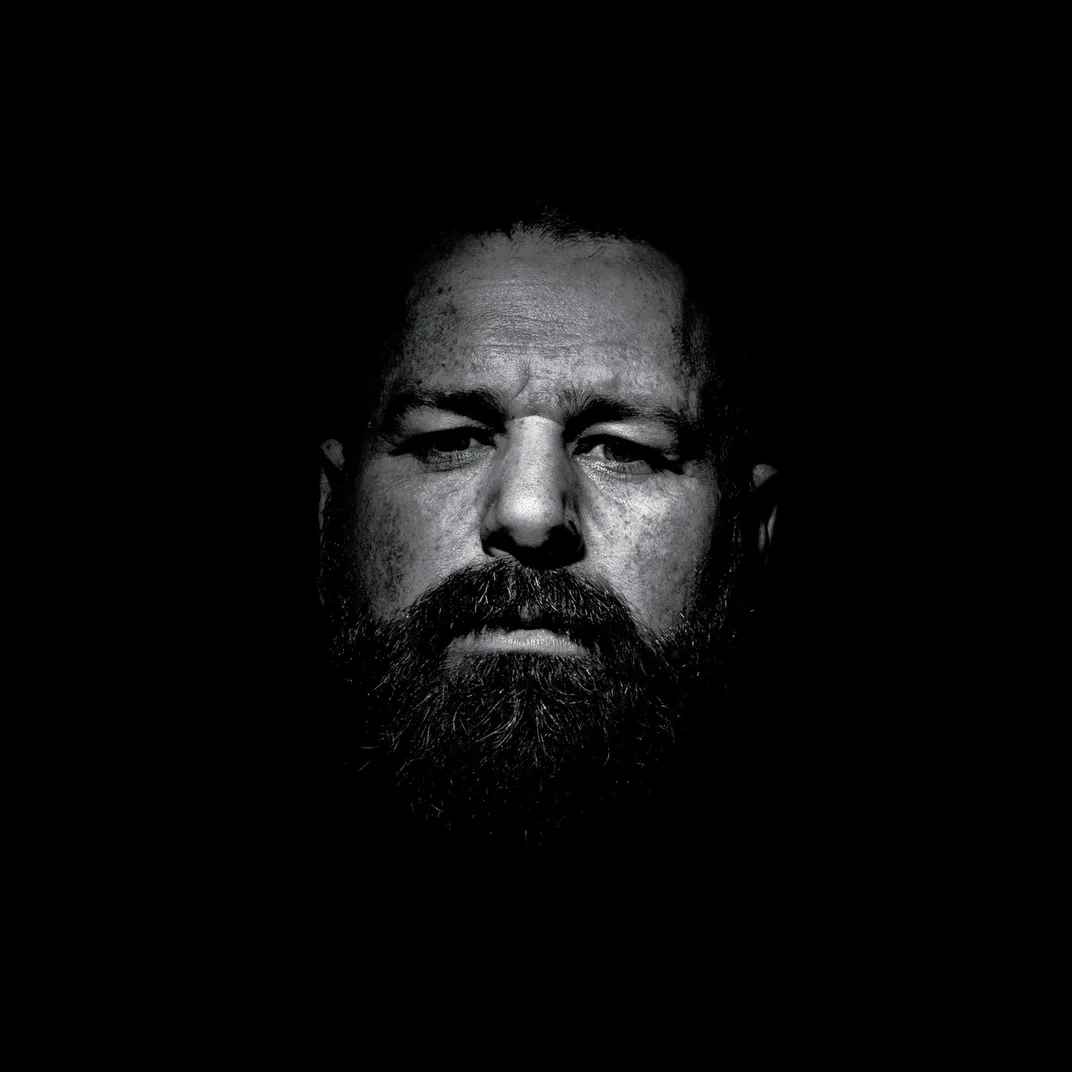

Eric Carson, 38, was chopping the mud with a short-handled fork that had long steel prongs. With one blue rubber-gloved hand, he moved aside a clump of seaweed. Crabs skittered away as the fork overturned mud. With his other hand he grabbed legal-size clams, at least two inches, tossing them into a basket. “It’s an extremely hard way to make a living,” he said with great understatement.

He had a beard the color of the tawny mud flats and around his eyes he had wrinkles formed by 20 years of squinting in the sun. “I didn’t start making any real money at it until after the first five years.”

The price posted that morning at the Gulf of Maine was $3 per pound. But it drops as low as $1.80 in winter. Harvesting is commonly closed because of red tides or rain. The market sometimes suddenly shuts down. In January, the flats are often frozen.

Carson had an extra fork. I tried digging. Perhaps I added eight ounces of clams to his basket in a half-hour. I broke about as many as I gathered, ruining them, and my back started hurting, so I stopped. Carson paused only to light a cigarette now and then.

When the tide rose, Carson took his clams in. The price, dictated by the market, had dropped to $2.50. A 77-year-old man, who told me that he dug “to pay the bills,” brought in ten pounds, and was paid $25. Carson had 86 pounds, a $215 payday.

Other than some long-ago start-up money that Sheehan got from Coastal Enterprises Inc., a community development corporation, the clammers are pretty much on their own, among a dwindling fraction of Americans who still manage to wrest a living from the land and sea.

I asked Carson if he thought of himself as poor. He said he didn’t think so. In the aughts, Carson and his girlfriend, Angela Francis, 34, lived in Bangor. He “ran equipment” and Francis worked at a Texas Roadhouse. They paid $750 a month rent. Francis got sick and had to quit. He cleared some $1,300, he said, “and if you take $750 from that, there’s not a whole lot left.” Now they live on two acres of land he inherited. When the couple moved from Bangor six years ago he bought an old 14- by 20-foot cabin for $500 and “loaded it on a flatbed and brought it there.” He built on additions. They grow a lot of food, canning tomatoes, beans, squash. Potatoes are stored for the winter. He cuts five cords of firewood to heat the house.

“I don’t need or want for too much else. My house is nothing lavish, but it’s mine. Taxes are $300 per year. I don’t have any credit cards. I don’t have a bank account. If you don’t have much overhead, you have nothing to worry about. I’ve created my own world. I don’t need anybody other than the people who buy the clams. Otherwise, it’s just us. It’s almost like a sovereign nation. We govern ourselves.”

**********

Driving back roads in Pennsylvania and Ohio, through former steel industry strongholds, including Johnstown and a string of rusting cities in the Monongahela Valley, I saw the two Americas, rich and poor. Downtown Pittsburgh, ballyhooed as having “come back” since the mills shuttered, glistened. Even Youngstown, emblematic of steel’s decline, has trendy downtown lofts and the “Las Vegas-style” Liquid Blu Nightclub. But always nearby, often within blocks, I found ruin and desperation.

In Cleveland, where the Republican National Convention had just been held, some close-in neighborhoods are being colonized by hipsters. Tymocs, a shot-and-beer joint in Tremont that my grandfather patronized after shifts at the B&O Railroad, is now Lucky’s Cafe, a brunch scene with pecan bacon and lemon waffles. But the overall picture is grim. Cleveland is the second-poorest large American city, census data show, with 39.2 percent of residents in poverty, just one-tenth of a point behind Detroit. The city is 53.3 percent black, 37.3 percent white.

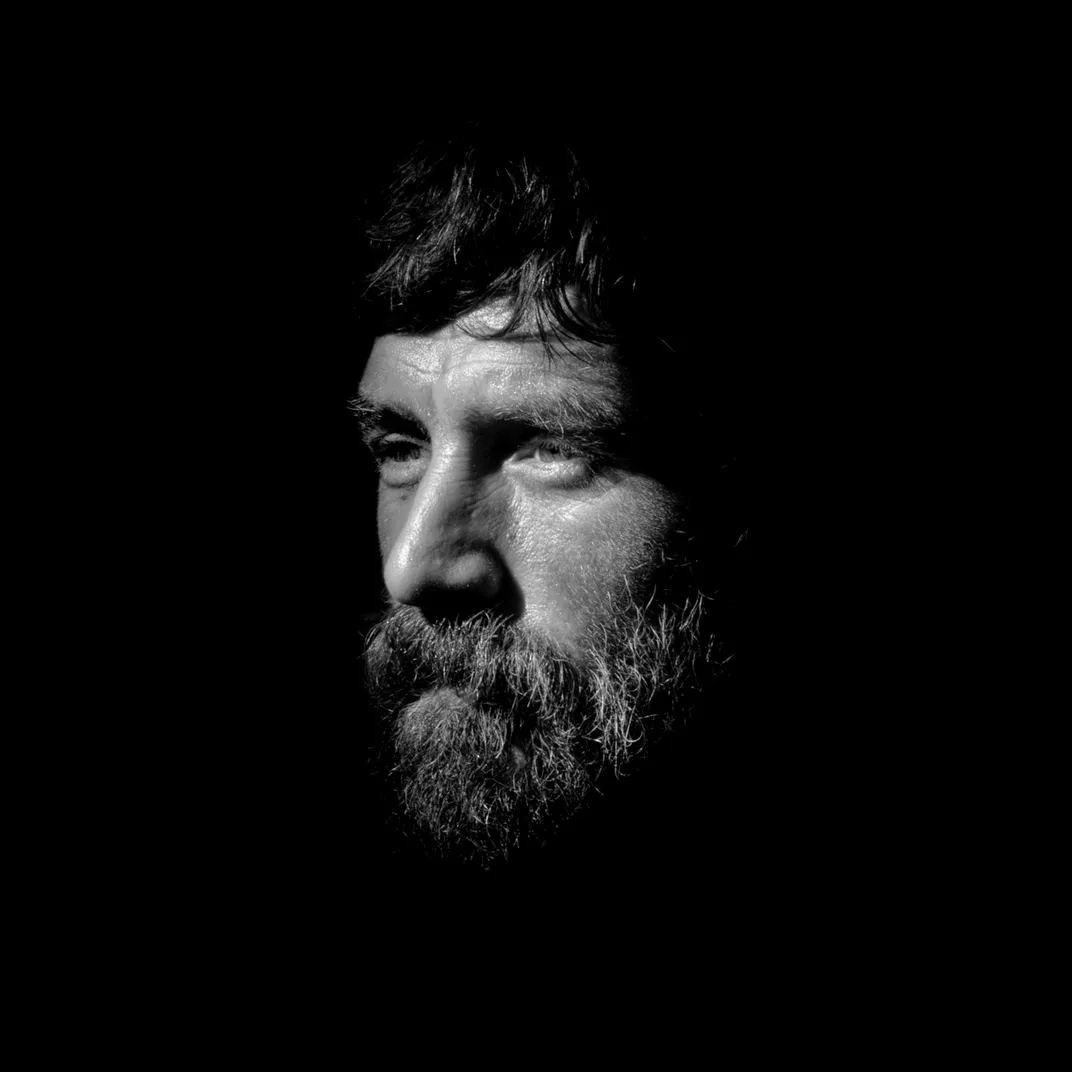

I headed to Glenville, a neighborhood that began a long decline after riots in 1968, and I ended up meeting Chris Brown, 41, at Tuscora Avenue and Lakeview Road.

Over 20 years earlier, Brown sold crack cocaine at this corner. “It was rough. In this neighborhood, if you weren’t selling crack, people looked at you funny.” He packed an Uzi. “I’d shoot it in the air. Any problems was gone, because I would tell them, ‘You might shoot me, but I’ll kill y’all.’” Brown shook his head. “Stupid,” he said in judgment of himself.

His early life began with promise. He’d gone off to college in 1993, and shortly after his girlfriend became pregnant. “I had a screaming, hollering baby,” he recalled. “No marketable skills. I got to feed this baby.” He dropped out and began dealing drugs. He knew he’d get busted someday. That day came in 1999. He points to the lawn where cops tackled him. He spent three years in prison.

“I’m going to tell you the game changer was going to prison,” he said. He took college classes. “It set me up to be serious.”

Visiting this corner wasn’t easy for Brown—his brow was furrowed and he spoke gravely. He showed what had been his “office” in an alley, now gone. Trees grow where one apartment building stood. The other’s roof has caved in. Empty lots and houses dot the area, which looks as if it was abandoned half a century ago. “No, man,” he said. “This is from 2000 on.” He pointed to where there had been a barbershop, hardware store, market, bakery. Crack, he said, “tore this neighborhood up.”

A sudden burst of gunfire, six to eight shots, interrupted our conversation. Close. Brown’s eyes darted. “Let’s get out of here. We’re in the open. We’re targets.”

We sped off in my rental car. “Ain’t no crack anymore,” he said. “The younger dudes, all they do is rob.”

I dropped Brown off at the Evergreen Laundry. It’s one of three cooperative Evergreen companies in Cleveland that employ a total of 125 people; there’s also an energy business and a hydroponic greenhouse. The Evergreen Cooperative Corporation is for-profit but owned by the workers. (It’s patterned after the Mondragón Corporation in Spain, one of the world’s largest cooperative businesses, with some 75,000 worker-owners.) Funding in part came from the Cleveland Foundation. The companies are tied to “anchor institutions” such as the renowned Cleveland Clinic, which buys lettuce, and University Hospitals, which has millions of pounds of laundry for the co-op.

After prison, Brown worked as a roofer and then at a telemarketing company. “I wasn’t really a salesman. I was selling gold-dipped coins. Crack? You didn’t have to talk nobody into that.” His previous job, as a janitor, had low pay and no benefits. The Evergreen Laundry paid him $10 an hour to start, with benefits. Six months later, he became plant supervisor.

I talked with different workers at the Evergreen companies, which have an average hourly wage of $13.94. Some 23 of them have purchased rehabilitated houses for $15,000 to $30,000 through an Evergreen program that deducts the loan from their pay. A worker owns the house free and clear in five years.

One afternoon, I volunteered in the three-and-a-quarter-acre hydroponic greenhouse. Cleveland Crisp and butter lettuce grow on serving-tray-size plastic foam “rafts” that float on 13 rectangular “ponds.” They begin as sprouts on one side and 39 days later, slowly pushed 330 feet, the rafts reach the far shore ready for harvest.

Workers hustled. A man transplanting lettuce “starts” was moving his hands at nearly a blur. Others plucked rafts and stacked them on giant carts. Our job was to put the rafts on a conveyor belt. If lettuce wasn’t fed into the refrigerated packing room fast enough, complaints came from inside. Some 10,800 heads of lettuce were shipped that day.

The harvest manager, Ernest Graham, and I talked as we worked. I mentioned the farmworkers in California. He said this is a better situation—the lettuce is eaten locally, no workers get abused and everyone is a co-owner. That really motivates workers, he said.

“This is the United States of America,” said Graham. “Greed is part of our M.O.” He mentioned income inequality. “We have significant wage gaps now,” he said. If the cooperative movement spreads and more people share in the wealth, “that’s where you want society to be. If everybody was well off it would be a better country. Can you imagine if every company was a co-op? Everyone would be happy.”

Begun in 2009, the Evergreen Cooperatives enterprise has been so successful it’s known as the “Cleveland Model,” and it’s being embraced by eight U.S. cities, including Albuquerque, New Orleans, Richmond and Rochester, New York. A half-dozen others are actively considering this co-op/social enterprise business approach because the “level of pain in many cities is so high and continuing to grow,” said Ted Howard, executive director of the Democracy Collaborative, a community development organization that helped start the Evergreen program.

For Brown, his work at the laundry was a fresh start. “This is my chance to right some of those wrongs,” he said of his past. “It’s like a shot at the title when you don’t deserve it. This makes my mother proud. My neighbors want to know about Evergreen.”

Brown earns less than his wife, who is an administrative assistant and show coordinator for a software engineering firm. On paper, he said, their combined income might make it appear that they’re doing fine. But then there are the bills.

The biggest ones?

“Mortgage and tuition,” Brown said, which amount to some $17,000 per year. “My stepson is in junior high school,” Brown explained. “He’s in a private school because our public school is garbage. That costs $8,000. You got to walk a fine line growing up black and poor. An education is an important thing. If we want to break the cycle, that’s where it starts, right there.”

As for the other expenses, food runs “three to four hundred a month.” The couple has one car, with a $350 monthly payment. Brown usually takes the bus to the Evergreen Laundry to start his 4 a.m. to 2 p.m. shift. They live paycheck to paycheck. “Save? I’m using everything I got to keep my head above water. It’s still always a struggle. I still ain’t made it where I don’t have to worry.”

I asked, Are you poor?

“I used to be poor. Poorness to me is you’re in a position to do things you don’t want to do,” he said, such as selling crack. “I might not make a lot of money, but I’ve got a job, I got a family, and I don’t have to be lookin’ over my shoulder. From where I come from, it’s night and day. What I’ve got that I didn’t have is hope.”

**********

"Louise” was Mary Lucille, then age 10—Agee had given all his subjects pseudonyms. Agee told her she could become a nurse or teacher and escape poverty. She didn’t. She sharecropped into the 1960s, then worked long hours at a café. On February 20, 1971, at the age of 45, she drank arsenic. “I wanna die,” she told her sister. “I’ve took all I can take.”

It was a brutal end to a brutally hard life. I grew close to three out of four of Lucille’s children—Patty, Sonny and Detsy. Patty and Sonny died too young in the ensuing years, alcoholism a factor for each. Last year, I visited Detsy in Florida, 30 years after we first met. She was now working a good job at a nearby hotel.

I’ve been on that story long enough to know that as much as I admire Agee’s work, I’m also painfully aware of the limitations of a poetic approach to writing about poverty. Many Americans have embraced a mythology about the Great Depression that there was national unity and shared suffering. The reality is the country was as divided then as it is today, with liberals or progressives calling for more government assistance and conservatives—John Steinbeck called them “rabid, hysterical Roosevelt hater(s)”—quick to blame and even villainize the poor.

Sure, many things have changed in the past 75 years. The vast majority of working poor people, starkly unlike the families Agee chronicled, live in dwellings with plumbing and electricity and television. They drive cars, not mule-drawn wagons. And just about everyone has a cellphone. Conservatives argue that today’s poor are “richer” because of these things, and have choices in a market-based economy; there are tax credits.

Living standards today are better. But the gap between rich and poor is still large, and growing, which adds a psychological dimension to poverty. More and more, Americans are increasingly either at the top or bottom. The middle class “may no longer be the economic majority in the U.S.,” according to a Pew Research Center study this year. The middle class has “lost ground in nine out of ten metropolitan areas.”

Poverty is not knowing if you’ll be able to pay the bills or feed your children. Some one in eight Americans, or 42.2 million people, are “food insecure,” which means they sometimes go hungry because they cannot afford a meal, according to Feeding America, the nationwide food bank. I’ve visited the homes of many working people and seen that, at the end of the month, before the next paycheck, the refrigerator is empty.

Agee and Evans documented the very peculiar system that was sharecropping, a feudal order that was an outgrowth of slavery. It was an extreme. In some ways it’s unfair to contrast that system with poverty today, other than in one important manner, told by way of a joke I once heard in Alabama: A tenant brings five bales of cotton to the gin. The landlord, after doing a lot of calculation, tells the tenant he broke even for the year. The tenant grows excited, and says to the landlord there’s one more bale back home that wouldn’t fit on the wagon. “Shucks,” the landlord replies. “Now I’ll have to figure it all over again so we can come out even.”

It’s virtually the same today for tens of millions of Americans who are “gainlessly” employed. They feel the system is gamed so that they always come out just even. I spoke with Salazar, the mechanic who works in a California raisin plant, about the minimum wage increase, to be phased in to $15 per hour by 2022.

Salazar shrugged. I asked why. “The cost of everything will just go up,” he said, and explained that merchants and others will charge more because they can. He doesn’t expect any extra money in his pocket.

Out of all the things I learned in my travels across America this summer and fall, the thing that stands out is the emergence of new for-profit social benefit organizations and cooperatives like Evergreen Corporation. They are one of the great untold stories of the past decade. These efforts are unprecedented in American history, and many can be traced to 2006, with the launch of B Lab, a nonprofit organization in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, that certifies B, or “benefit” corporations that “use the power of markets to solve social and environmental problems.” There are now nearly 1,700 B corporations.

In 2008, Vermont became the first state to recognize low-profit limited liability corporations, or L3Cs, that focus on “social impact investing.” There are now “a couple of thousand” L3Cs in numerous states, says Bob Lang, CEO of the Mary Elizabeth & Gordon B. Mannweiler Foundation, which advocates using for-profit vehicles to achieve charitable missions.

More than 200 new worker-owned cooperatives have formed since 2000, according to Project Equity and the Democracy at Work Institute. The forecast is for growth. In Cleveland, the Evergreen companies envision a tenfold increase in jobs, to someday have 1,000 worker-owners. It’s heartening to see these things happening after more than 30 years of covering working-class issues and poverty.

For some people stuck at the bottom of the poverty scale, however, the bar for what they see as improving their lives is far lower than the one set by Evergreen’s high ambitions. In one of my conversations with Graham, the greenhouse harvest manager, we veered into criticizing Walmart, which is fairly notorious for its low-wage jobs, often part-time, and often without benefits.

Then I remembered something Martha said. We were standing outside amid the dust in the blazing California sun. She dreamily described her ideal job. It would be inside, she said, in a clean, air-conditioned place, out of the dirt and heat. “Everyone here wants to get out of here,” she said, looking around The Scissors. “I would love to be able to work at Walmart.”

This story was supported by the journalism non-profit The Economic Hardship Reporting Project.