A Photographic Requiem for America’s Civil War Battlefields

Walking far-flung battlefields to picture the nation’s defining tragedy in a modern light

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/16/63169087-1a27-49af-b4dc-be2b2278aff1/julaug2015_dudik_cover.jpg)

In “Poem of Wonder at the Resurrection of the Wheat,” Walt Whitman describes a landscape that is oblivious to human suffering, with “innocent and disdainful” summer crops rising out of the same ground where generations lie buried. He published the lyric in 1856, not long before the Civil War transformed peach orchards and wheat fields into vistas of mortal anguish.

The “Broken Land” photography series, by Eliot Dudik, seems to challenge Whitman’s vision of an indifferent earth: In these battlefield panoramas, the new life of 150 summers can’t seem to displace death. Seasonal change is just another ghostly note in these images. Fresh snow, high cotton—it hardly matters. Moss advances in Shenandoah River bottoms and clouds storm Lookout Mountain, but nature never conquers memory here. The soil still looks red.

Dudik, who spent his childhood in Pennsylvania, moved to South Carolina in 2004. “Conversations there always seemed to turn toward the Civil War,” he says, and that made him “realize the importance of remembering and considering.” He embarked on “Broken Land” three years ago, and so far has photographed about a hundred battlegrounds in 24 states. He’s now founding a photography program at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia; this summer, while he’s on break, he hopes to add battlegrounds in three more states.

Using an antique view camera that weighs 50 pounds, he typically takes only a single, painstaking picture of each battlefield he visits. He prefers to shoot in winter, and “in rain, and on really overcast and nasty days. Blue sky is kind of my nemesis.” The subdued light makes landscapes look perfectly even. “I avoid the grandiose, the spectacular, the beautiful. It helps the viewer consider what’s being photographed.”

In Dudik’s pictures, trees are everywhere. “If I could take pictures of trees for the rest of my life, I would,” he says. He likes how their vertical forms balance long horizons, but they are spiritual presences, too. They go gray or blue, depending on the light. They hold the line, beckon, surrender:

Related Reads

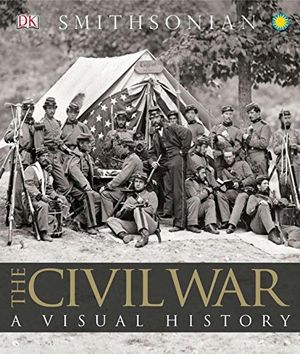

The Civil War: A Visual History