Power and the Presidency, From Kennedy to Obama

For the past 50 years, the commander in chief has steadily expanded presidential power, particularly in foreign policy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presidency-Power-JFK-with-Robert-631.jpg)

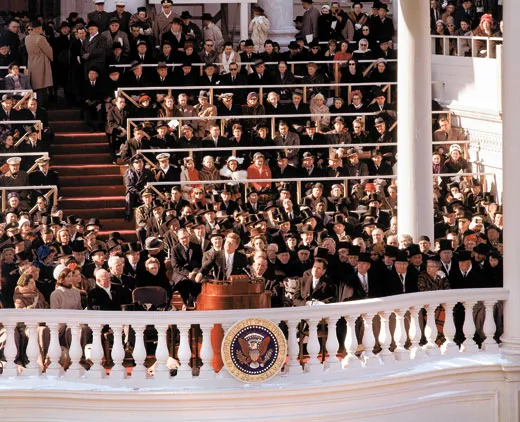

Fifty Januaries ago, under a pallid sun and amid bitter winds, John F. Kennedy swore the oath that every president had taken since 1789 and then delivered one of the most memorable inaugural addresses in the American canon. “We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom,” the 35th president began. After noting that “the world is very different now” from the world of the Framers because “man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life,” he announced that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans” and made the pledge that has echoed ever since: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.”

After discoursing on the challenges of eradicating hunger and disease and the necessity of global cooperation in the cause of peace, he declared that “[i]n the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger.” Then he issued the call for which he is best remembered: “And so, my fellows Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

The address was immediately recognized as ex-ceptionally eloquent—“a rallying cry” (the Chicago Tribune), “a speech of rededication” (the Philadelphia Bulletin), “a call to action which Americans have needed to hear for many a year” (the Denver Post)—and acutely attuned to a moment that promised both advances in American prowess and grave peril from Soviet expansion. As James Reston wrote in his column for the New York Times, “The problems before the Kennedy Administration on Inauguration Day are much more difficult than the nation has yet come to believe.”

In meeting the challenges of his time, Kennedy sharply expanded the power of the presidency, particularly in foreign affairs. The 50th anniversary of his inauguration highlights the consequences—for him, for his successors and for the American people.

To be sure, the President’s control over foreign affairs had been growing since the Theodore Roosevelt administration (and still grows today). TR’s acquisition of the Panama Canal Zone preceded Woodrow Wilson’s decision to enter World War I, which was a prelude to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s management of the run-up to the victorious American effort in World War II. In the 1950s, Harry S. Truman’s response to the Soviet threat included the decision to fight in Korea without a Congressional declaration of war, and Dwight Eisenhower used the Central Intelligence Agency and brinksmanship to contain Communism. Nineteenth-century presidents had had to contend with Congressional influences in foreign affairs, and particularly with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. But by the early 1960s, the president had become the undisputed architect of U.S. foreign policy.

One reason for this was the emergence of the United States as a great power with global obligations. Neither Wilson nor FDR could have imagined taking the country to war without a Congressional declaration, but the exigencies of the cold war in the 1950s heightened the country’s reliance on the president to defend its interests. Truman could enter the Korean conflict without having to seek Congressional approval simply by describing the deployment of U.S. troops as a police action taken in conjunction with the United Nations.

But Truman would learn a paradoxical, and in his case bitter, corollary: with greater power, the president also had a greater need to win popular backing for his policies. After the Korean War had become a stalemate, a majority of Americans described their country’s participation in the conflict as a mistake—and Truman’s approval ratings fell into the twenties.

After Truman’s experience, Eisenhower understood that Americans still looked to the White House for answers to foreign threats—as long as those answers did not exceed certain limits in blood and treasure. By ending the fighting in Korea and holding Communist expansion to a minimum without another limited war, Eisenhower won re-election in 1956 and maintained public backing for his control of foreign affairs.

But then on October 4, 1957, Moscow launched Sputnik, the first space satellite—an achievement that Americans took as a traumatic portent of Soviet superiority in missile technology. Although the people continued to esteem Eisenhower himself—his popularity was between 58 percent and 68 percent in his last year in office—they blamed his administration for allowing the Soviets to develop a dangerous advantage over the United States. (Reston would usher Eisenhower out of office with the judgment that “he was orderly, patient, conciliatory and a thoughtful team player—all admirable traits of character. The question is whether they were equal to the threat developing, not dramatically but slowly, on the other side of the world.”) Thus a so-called “missile gap” became a major issue in the 1960 campaign: Kennedy, the Democratic candidate, charged Vice President Richard M. Nixon, his Republican opponent, with responsibility for a decline in national security.

Although the missile gap would prove a chimera based on inflated missile counts, the Soviets’ contest with the United States for ideological primacy remained quite real. Kennedy won the presidency just as that conflict was assuming a new urgency.

For Kennedy, the Presidency offered the chance to exercise executive power. After serving three terms as a congressman, he said, “We were just worms in the House—nobody paid much attention to us nationally.” His seven years in the Senate didn’t suit him much better. When he explained in a 1960 tape recording why he was running for president, he described a senator’s life as less satisfying than that of a chief executive, who could nullify a legislator’s hard-fought and possibly long-term initiative with a stroke of the pen. Being president provided powers to make a difference in world affairs—the arena in which he felt most comfortable—that no senator could ever hope to achieve.

Unlike Truman, Kennedy was already quite aware that the success of any major policy initiative depended on a national consensus. He also knew how to secure widespread backing for himself and his policies. His four prime-time campaign debates against Nixon had heralded the rise of television as a force in politics; as president, Kennedy held live televised press conferences, which the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who was a special assistant in the Kennedy White House, would recall as “a superb show, always gay, often exciting, relished by the reporters and by the television audience.” Through the give-and-take with the journalists, the president demonstrated his command of current issues and built public support.

Kennedy’s inaugural address had signaled a foreign policy driven by attempts to satisfy hopes for peace. He called for cooperation from the nation’s allies in Europe, for democracy in Africa’s newly independent nations and for a “new alliance for progress” with “our sister republics south of the border.” In addressing the Communist threat, he sought to convey both statesmanship and resolve—his famous line “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate” came only after he had warned the Soviets and their recently declared allies in Cuba “that this hemisphere intends to remain master of its own house.”

Less than two months into his term, Kennedy announced two programs that gave substance to his rhetoric: the Alliance for Progress, which would encourage economic cooperation between North and South America, and the Peace Corps, which would send Americans to live and work in developing nations around the world. Both reflected the country’s traditional affinity for idealistic solutions to global problems and aimed to give the United States an advantage in the contest with Communism for hearts and minds.

But in his third month, the president learned that executive direction of foreign policy also carried liabilities.

Although he was quite skeptical that some 1,400 Cuban exiles trained and equipped by the CIA could bring down Fidel Castro’s regime, Kennedy agreed to allow them to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. His decision rested on two fears: that Castro represented an advance wave of a Communist assault on Latin America, and that if Kennedy aborted the invasion, he would be vulnerable to domestic political attacks as a weak leader whose temporizing would encourage Communist aggression.

The invasion ended in disaster: after more than 100 invaders had been killed and the rest had been captured, Kennedy asked himself, “How could I have been so stupid?” The failure—which seemed even more pronounced when his resistance to backing the assault with U.S. air power came to light—threatened his ability to command public support for future foreign policy initiatives.

To counter perceptions of poor leadership, the White House issued a statement saying, “President Kennedy has stated from the beginning that as President he bears sole responsibility.” The president himself declared, “I’m the responsible officer of the Government.” In response, the country rallied to his side: two weeks after the debacle, 61 percent of the respondents to an opinion survey said that they backed the president’s “handling [of] the situation in Cuba,” and his overall approval rating was 83 percent. Kennedy joked, “The worse I do, the more popular I get.”

Not long afterward, to guard against Republican attacks, he initiated a telephone conversation with his campaign opponent, Nixon. “It really is true that foreign affairs is the only important issue for a President to handle, isn’t it?” he asked rhetorically. “I mean, who gives a s--- if the minimum wage is $1.15 or $1.25, in comparison to something like this?” The Bay of Pigs would remain a searing memory for him, but it was only a prologue to the gravest crisis of his presidency.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to place medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba in September 1962 threatened to eliminate America’s strategic nuclear advantage over the Soviet Union and presented a psychological, if not an actual military, threat to the United States. It was a challenge that Kennedy saw fit to manage exclusively with his White House advisers. The Executive Committee of the National Security Council—ExComm, as it became known—included not a single member of Congress or the judiciary, only Kennedy’s national security officials and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and his vice president, Lyndon Johnson. Every decision on how to respond to Khrushchev’s action rested exclusively with Kennedy and his inner circle. On October 16, 1962—while his administration was gathering intelligence on the new threat, but before making it public—he betrayed a hint of his isolation by reciting, during a speech to journalists at the State Department, a version of a rhyme by a bullfighter named Domingo Ortega:

Bullfight critics row on row

Crowd the enormous plaza de toros

But only one is there who knows

And he’s the one who fights the bull.

While ExComm deliberated, concerns about domestic and international opinion were never far from Kennedy’s thinking. He knew that if he responded ineffectually, domestic opponents would attack him for setting back the nation’s security, and allies abroad would doubt his resolve to meet Soviet threats to their safety. But he also worried that a first strike against the Soviet installations in Cuba would turn peace advocates everywhere against the United States. Kennedy told former Secretary of State Dean Acheson a U.S. bombing raid would be seen as “Pearl Harbor in reverse.”

To avoid being seen as an aggressor, Kennedy initiated a marine “quarantine” of Cuba, in which U.S. ships would intercept vessels suspected of delivering weapons. (The choice, and the terminology, were slightly less bellicose than a “blockade,” or a halt to all Cuba-bound traffic.) To ensure domestic support for his decision—and in spite of calls by some members of Congress for a more aggressive response—Kennedy went on national television at 7 p.m. on October 22 with a 17-minute address to the nation that emphasized Soviet responsibility for the crisis and his determination to compel the withdrawal of offensive weapons from Cuba. His intent was to build a consensus not merely for the quarantine but also for any potential military conflict with the Soviet Union.

That potential, however, went unfulfilled: after 13 days in which the two sides might have come to nuclear blows, the Soviets agreed to remove their missiles from Cuba in exchange for a guarantee that the United States would respect the island’s sovereignty (and, secretly, remove U.S. missiles from Italy and Turkey). This peaceful resolution strengthened both Kennedy’s and the public’s affinity for unilateral executive control of foreign policy. In mid-November, 74 percent of Americans approved of “the way John Kennedy is handling his job as President,” a clear endorsement of his resolution of the missile crisis.

When it came to Vietnam, where he felt compelled to increase the number of U.S. military advisers from some 600 to more than 16,000 to save Saigon from a Communist takeover, Kennedy saw nothing but trouble from a land war that would bog down U.S. forces. He told New York Times columnist Arthur Krock that “United States troops should not be involved on the Asian mainland....The United States can’t interfere in civil disturbances, and it is hard to prove that this wasn’t the situation in Vietnam.” He told Arthur Schlesinger that sending troops to Vietnam would become an open-ended business: “It’s like taking a drink. The effect wears off, and you have to take another.” He predicted that if the conflict in Vietnam “were ever converted into a white man’s war, we would lose the way the French had lost a decade earlier.”

Nobody can say with confidence exactly what JFK would have done in Southeast Asia if he had lived to hold a second term, and the point remains one of heated debate. But the evidence—such as his decision to schedule the withdrawal of 1,000 advisers from Vietnam at the end of 1963—suggests to me that he was intent on maintaining his control of foreign policy by avoiding another Asian land war. Instead, the challenges of Vietnam fell to Lyndon Johnson, who became president upon Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963.

Johnson, like his immediate predecessors, assumed that decisions about war and peace had largely become the president’s. True, he wanted a show of Congressional backing for any major steps he took—hence the Tonkin Gulf Resolution in 1964, which authorized him to use conventional military force in Southeast Asia. But as the cold war accelerated events overseas, Johnson assumed he had license to make unilateral judgments on how to proceed in Vietnam. It was a miscalculation that would cripple his presidency.

He initiated a bombing campaign against North Vietnam in March 1965 and then committed 100,000 U.S. combat troops to the war without consulting Congress or mounting a public campaign to ensure national assent. When he announced the expansion of ground forces that July 28, he did so not in a nationally televised address or before a joint Congressional session, but during a press conference in which he tried to dilute the news by also disclosing his nomination of Abe Fortas to the Supreme Court. Similarly, after he decided to commit an additional 120,000 U.S. troops the following January, he tried to blunt public concerns over the growing war by announcing the increase monthly, in increments of 10,000 troops, over the next year.

But Johnson could not control the pace of the war, and as it turned into a long-term struggle costing the United States thousands of lives, increasing numbers of Americans questioned the wisdom of fighting what had begun to seem like an unwinnable conflict. In August 1967, R. W. Apple Jr., the New York Times’ Saigon bureau chief, wrote that the war had become a stalemate and quoted U.S. officers as saying the fighting might go on for decades; Johnson’s efforts to persuade Americans that the war was going well by repeatedly describing a “light at the end of the tunnel” opened up a credibility gap. How do you know when LBJ is telling the truth? a period joke began. When he pulls his ear lobe and rubs his chin, he is telling the truth. But when he begins to move his lips, you know he’s lying.

Antiwar protests, with pickets outside the White House chanting, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” suggested the erosion of Johnson’s political support. By 1968, it was clear that he had little hope of winning re-election. On March 31, he announced that he would not run for another term and that he planned to begin peace talks in Paris.

The unpopular war and Johnson’s political demise signaled a turn against executive dominance of foreign policy, particularly of a president’s freedom to lead the country into a foreign conflict unilaterally. Conservatives, who were already distressed by the expansion of social programs in his Great Society initiative, saw the Johnson presidency as an assault on traditional freedoms at home and an unwise use of American power abroad; liberals favored Johnson’s initiatives to reduce poverty and make America a more just society, but they had little sympathy for a war they believed was unnecessary to protect the country’s security and wasted precious resources. Still, Johnson’s successor in the White House, Richard Nixon, sought as much latitude as he could manage.

Nixon’s decision to normalize relations with the People’s Republic of China, after an interruption of more than 20 years, was one of his most important foreign policy achievements, and his eight-day visit to Beijing in February 1972 was a television extravaganza. But he planned the move in such secrecy that he didn’t notify members of his own cabinet—including his secretary of state, William Rogers—until the last minute, and instead used his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, to pave the way. Similarly, Nixon relied on Kissinger to conduct back-channel discussions with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin before traveling to Moscow in April 1972 to advance a policy of détente with the Soviet Union.

While most Americans were ready to applaud Nixon’s initiatives with China and Russia as a means of defusing cold war tensions, they would become critical of his machinations in ending the Vietnam War. During his 1968 presidential campaign, he had secretly advised South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu to resist peace overtures until after the U.S. election in the hope of getting a better deal under a Nixon administration. Nixon’s action did not become public until 1980, when Anna Chennault, a principal figure in the behind-the-scenes maneuvers, revealed them, but Johnson learned of Nixon’s machinations during the 1968 campaign; he contended that Nixon’s delay of peace talks violated the Logan Act, which forbids private citizens from interfering in official negotiations. Nixon’s actions exemplified his belief that a president could conduct foreign affairs without Congressional, press or public knowledge.

Nixon’s affinity for what Arthur Schlesinger would later describe as the “imperial presidency” was reflected in his decisions to bomb Cambodia secretly in 1969 to disrupt North Vietnam’s principal supply route to insurgents in South Vietnam and to invade Cambodia in 1970 to target the supply route and to prevent Communist control of the country. Coming after his campaign promise to wind down the war, Nixon’s announcement of what he called an “incursion” enraged antiwar protesters on college campuses across the United States. In the ensuing unrest, four students at Kent State University in Ohio and two at Jackson State University in Mississippi were fatally shot by National Guard troops and police, respectively.

Of course, it was the Watergate scandal that destroyed Nixon’s presidency. The revelations that he had deceived the public and Congress as the scandal unfolded also undermined presidential power. The continuing belief that Truman had trapped the United States in an unwinnable land war in Asia by crossing the 38th Parallel in Korea, the distress at Johnson’s judgment in leading the country into Vietnam, and the perception that Nixon had prolonged the war there for another four years—a war that would cost the lives of more than 58,000 U.S. troops, more than in any foreign war save for World War II—provoked national cynicism about presidential leadership.

The Supreme Court, in ruling in 1974 that Nixon had to release White House tape recordings that revealed his actions on Watergate, reined in presidential powers and reasserted the influence of the judiciary. And in response to Nixon’s conduct of the war in Southeast Asia, Congress, in 1973, passed the War Powers Resolution over his veto in an attempt to rebalance its constitutional power to declare war. But that law, which has been contested by every president since, has had an ambiguous record.

Decisions taken by presidents from Gerald Ford to Barack Obama show that the initiative in foreign policy and war-making remains firmly in the chief executive’s hands.

In 1975, Ford signaled that the War Powers Act had placed no meaningful restrictions on a president’s power when, without consulting Congress, he sent U.S. commandos to liberate American seamen seized from the cargo ship Mayaguez by the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia’s Communist government. When the operation cost 41 military lives to rescue 39 sailors, he suffered in the court of public opinion. And yet the result of Ford’s action did not keep Jimmy Carter, his successor, from sending a secret military mission into Iran in 1980 to free American hostages held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Carter could justify the secrecy as essential to the mission, but after sandstorms and a helicopter crash aborted it, confidence in independent executive action waned. Ronald Reagan informed Congress of his decisions to commit U.S. troops to actions in Lebanon and Grenada, then suffered from the Iran-Contra scandal, in which members of his administration plotted to raise funds for anti-Communists in Nicaragua—a form of aid that Congress had explicitly outlawed.

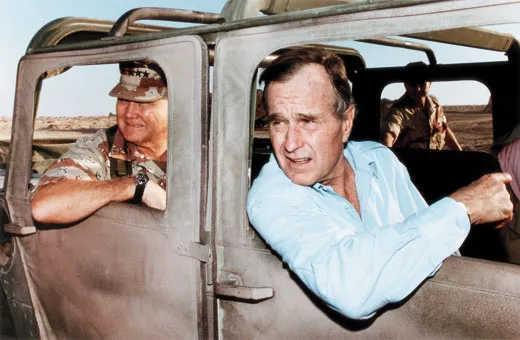

George H.W. Bush won a Congressional resolution supporting his decision to oust Iraqi forces from Kuwait in 1991. At the same time, he unilaterally chose not to expand the conflict into Iraq, but even that assertion of power was seen as a bow to Congressional and public opposition to a wider war. And while Bill Clinton chose to consult with Congressional leaders on operations to enforce a U.N. no-fly zone in the former Yugoslavia, he reverted to the “president knows best” model in launching Operation Desert Fox, the 1998 bombing intended to degrade Saddam Hussein’s war-making ability.

After the terrorist attacks of September 2001, George W. Bush won Congressional resolutions backing the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, but both were substantial military actions that under any traditional reading of the Constitution required declarations of war. The unresolved problems attached to these conflicts have once again raised concerns about the wisdom of fighting wars without more definitive support. At the end of Bush’s term, his approval ratings, like Truman’s, fell into the twenties.

Barack Obama does not appear to have fully grasped the Truman lesson on the political risks of unilateral executive action in foreign affairs. His decision in late 2009 to expand the war in Afghanistan—albeit with withdrawal timelines—rekindled worries about an imperial presidency. Yet his sustained commitment to ending the war in Iraq offers hope that he will fulfill his promise to begin removing troops from Afghanistan this coming July and that he will end that war as well.

Perhaps the lesson to be taken from the presidents since Kennedy is one Arthur Schlesinger suggested almost 40 years ago, writing about Nixon: “The effective means of controlling the presidency lay less in law than in politics. For the American President ruled by influence; and the withdrawal of consent, by Congress, by the press, by public opinion, could bring any President down.” Schlesinger also quoted Theodore Roosevelt, who, as the first modern practitioner of expanded presidential power, was mindful of the dangers it posed for the country’s democratic traditions: “I think it [the presidency] should be a very powerful office,” TR said, “and I think the president should be a very strong man who uses without hesitation every power that the position yields; but because of this fact I believe that he should be closely watched by the people [and] held to a strict accountability by them.”

The issue of accountability is with us still.

Robert Dallek’s most recent book is The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945-1953.