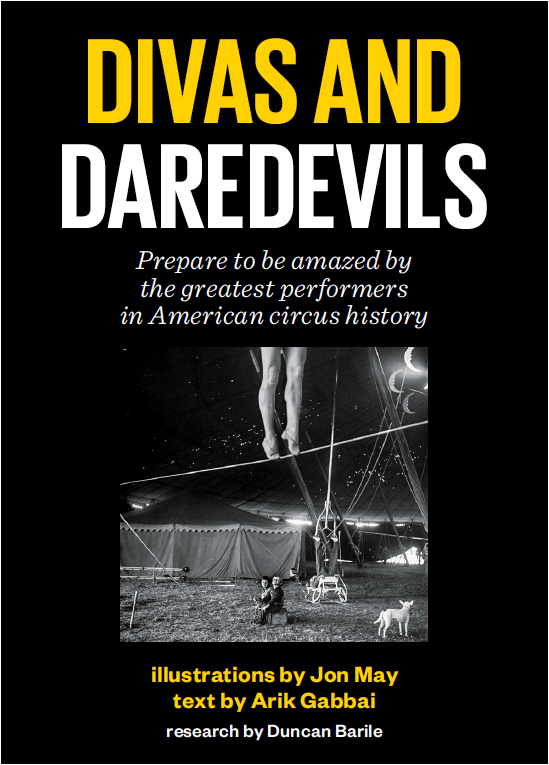

Step Right Up! See the Reinvention of the Great American Circus!

As Ringling Bros. packs up its tent for good, all sorts of newfangled spectacles have sprung up to take its place

:focal(2240x891:2241x892)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/be/c0bef4be-52ed-415a-8418-f1ccf334bc0d/julaug2017_k15_circus.jpg)

Printed in red capital letters on the back of the instructor’s black T-shirt is what seems to me a loaded question: WHY WALK WHEN YOU CAN FLY?

Looking down from nearly 20 feet up in the air, perched atop a 5-foot-wide platform, I can tell you why. I’m afraid of heights. I have a bad shoulder. There’s no such thing as “the friendly skies.” Furthermore, if jumping from this platform and dangling from a steel pole is safe, why did I have to sign a liability waiver?

“You can do it!” shouts our instructor, Ailsa “Al” Firstenberg, from below, flashing two thumbs up. My six classmates at trapeze school, all younger than I, look less certain, but are visibly riveted by my evident panic and the potential for disaster.

Standing beside me, another instructor, Patrick Howlett, an Australian doppelgänger for actor Chris Hemsworth, extends a Thor-like arm and catches the bar a co-worker on the far opposite platform sends sailing our way. Patrick smiles. “Come on, Hols,” he purrs, instantly nicknaming me. “Time to fly.”

It is so not time to fly. Just scaling the ladder without supplemental oxygen induced colon cramps. Going down? I think. No way.

Mind you, I’m no wimp. I’ve survived dangerous assignments: swimming with sharks in the Caribbean; riding a water buffalo in Brazilian rainforest; standing in line at a Nicholas Sparks book signing in Greenville, South Carolina.

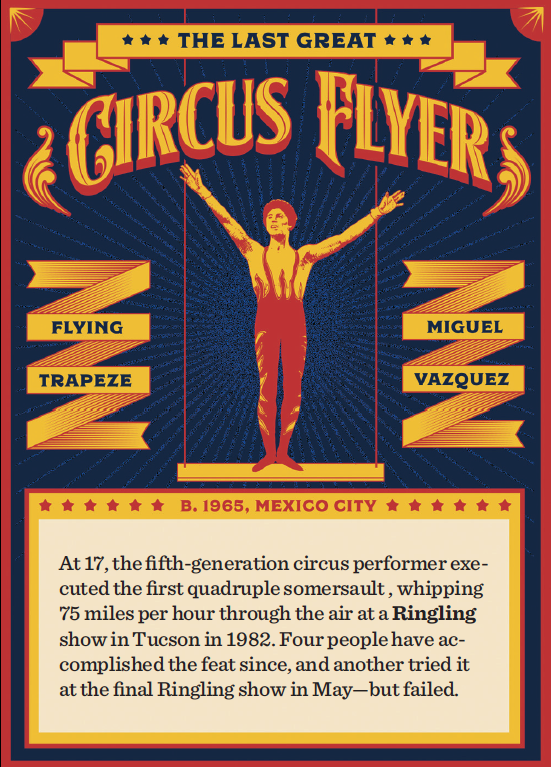

Surely flying at España-Streb Trapeze Academy in Williamsburg, Brooklyn is not going to kill me. Right? Learning the flying trapeze is, after all, the most popular offspring of the traditional traveling circus, whose demise has unearthed a flourishing ecosystem of boutique circuses and participatory upstarts across the country. Though the Ringling Bros. retired in May, dry your eyes and pop your clown nose on; there are plenty more circuses you can visit wide-eyed or run away to and join.

No joke: Circus scholar Janet Davis counts some 85 circus schools and training centers scattered across the country, where everyone from bona fide big-top and art-house pros to curious civilians and energetic youngsters learn the ropes, high wires and German wheels of circus yore. More grounded types can master juggling and clowning arts, while fitness fanatics elevate into yoga aerialists and trampoline acrobats.

And roving troupes and single-ring spectacles abound. Ninety percent of us live within an hour’s drive of a performing circus, according to the World Circus Federation, each with its own special flair for wow. Like Circus Amok, whose clowns in drag perform free outdoor shows, spotlighting social issues from AIDS to immigration to gentrification. Or Absinthe, a naughty Las Vegas cabaret-circus hybrid the New York Times cheers as “Cirque du Soleil as channeled through the Rocky Horror Picture Show.” Cirque des Voix, based in Sarasota, Florida, sets aerial routines to choral music performed by more than a hundred singers and a 40-piece orchestra, and Atlanta-based UniverSoul, the only African-American-owned circus, is an extravaganza of black culture from around the world. From Montreal, there’s Les 7 Doigts de la Main (The Seven Fingers of the Hand), which recently toured the United States with its show “Cuisine & Confessions,” in which a juggling, dancing, storytelling, acrobatic troupe also cooks and feeds the audience.

In simpler times, the big top was a thrilling escape from monotony. In today’s topsy-turvy world, these shows and scores of others offer an interactive and intimate respite from our tech-age overload—our emails, smartphones, Twitter feeds, queued-up Netflix TV shows, all demanding our attention, stealing our time, depriving us of memories.

Hence, my heart-pounding predicament at the España-Streb Trapeze Academy, which was founded by renowned acrobatic choreographer Elizabeth Streb and fifth-generation circus legends Noe and Ivan España, where almost everybody can learn to fly, as long as they’re between the ages of 5 and 85.

I grasp the trapeze bar in one hand while Patrick moves behind me to grip my safety belt, so I can lean forward beyond the platform to grab the distant other end with my free hand.

“The bar is heavy, so you’re going to feel like you want to bend forward,” Patrick says. “But keep your shoulders back and push your hips forward, nice and tall. Do not look down.”

Stretched out over the abyss, white-knuckling the bar, I wait for a spotter named Viktor, manning the safety ropes on my belt from below, to call out the commands. “Ready” means bend the knees. “Hep” means go. (Circus people tend not to say “go,” as it could be mistaken for “no.”)

“Ready! Hep!”

I jump, stunned by the cement weight of my body, which threatens to rip away from my shoulders and leave my limbs behind on the bar. My hands burn. I’m about to give up, let go, cry Uncle!, when the tonnage of flesh and bones and blood lightens on the upswing, and the magical sensation of flying kicks in. At the highest point, I feel featherweight and roller-coaster giddy as the air holds me in its breath before releasing me to swing back again.

It’s physics, Viktor explains later. “When you’re vertical, you experience three times your body weight in your grip. At apex—when your body peaks horizontal to the floor—you’re weightless.” (This is the moment when acrobats do tricks.)

Four trips up the ladder later and I’m launching myself, swinging upside down by my knees, and dismounting with a back flip into the gigantic airbag below, a superhero with a newfound power and an ego to match.

**********

Smithsonian Folklife Festival Highlights the Circus

Smithsonian Folklife Festival Highlights the Circus

Smithsonian Folklife Festival Highlights the Circus

Do you speak Circus? Yes, you do! Ever ordered jumbo fries? Those are named for the plus-sized zoo elephant bought and made famous by P.T. Barnum in 1882. Called someone a geek? That’s a sideshow freak. Gotten the show on the road or jumped on the bandwagon? Or—my personal favorite—been ditched? If so, the circus didn’t bother to formally fire you—it just left you standing beside the tracks after the train deviously pulled out of the station early.

For the citizens and 54 railway cars of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus Xtreme, Providence, Rhode Island, is the last stop on the line. Kenneth Feld, whose family owns the circus, appears and thanks the sold-out crowd of 14,000 for 146 years of “making the impossible possible. And now, for the Greatest Show on Earth—one last time!”

The long-ballyhooed goodbye begins! There are fire jugglers, camel-riding contortionists, glow-in-the-dark bungee-jumping acrobats, snake charmers wrapped in bright yellow pythons, a Mongolian strongman who lifts a 551-pound mass of Mongol gals and kettlebells with his “jaws of steel.” Clowns pop up and out all over the place, and I’m gleefully overstimulated. Then a 20-foot cannon, wheeled into the ring, grabs my attention. A fuse is lit. The audience counts down from five and bang! “Nitro” Nicole Sanders flies more than a hundred feet at 66 miles per hour into the pillowy embrace of a giant airbag, just as pioneer cannonballer Rosa “Zazel” Richter did 140 years earlier. And who rigged the first human cannon, you ask? That was funambulist (tightrope walker) William Leonard Hunt, a.k.a. the Great Farini, which raises the question, why wasn’t he the first human cannonball? (“Zazel, you go first.”)

After the blast, “Nitro” Nicole takes a bow, and intermission is announced with a reminder of how much the world has changed: “In the event of firearms, stay calm and look for the nearest exit.”

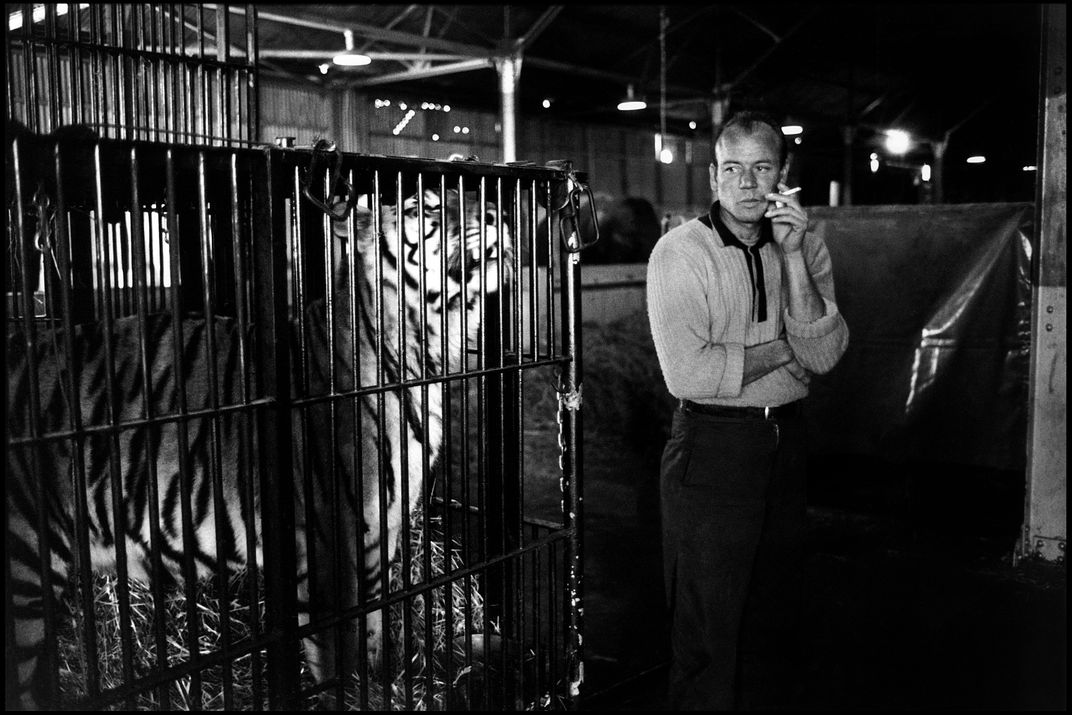

The highlight of the second half includes 12 tigers strutting inside a massive cage, encircling their buff, bald-headed trainer, Tabayara “Taba” Maluenda, a sixth-generation Chilean circus performer dressed in a bedazzled green sleeveless velvet jumpsuit, matching armbands and knee-high leather boots. With a flick of Taba’s whip, the regal beasts sit, jump from stool to stool, lie down side by side, roll over one after the other. Taba sweats bullets throughout, mopping his mug. But when he faces us and takes a bow, it’s clear those are tears streaming down his face.

The trainer turns and kisses one of the man-eaters on the nose. Sobbing, he addresses them. “For 30 years you put food on my table,” he says. “Catana, I have had you for 13 years, since you were 6 months old.” He calls Catana to him and buries his head in her fur. Then he dismisses the cats one by one, thanking each by name. With the last one gone, Taba kisses the empty floor.

To close the evening, and an era, Kristen Michelle Wilson, Ringling’s first (and last) female ringmaster, calls some 300 cast and crew into the ring, to sing “Auld Lang Syne.” From backstage, husbands, wives and children come join them. None of the babies are crying, but all of the grown-ups are.

“We circus people always say, ‘We’ll see you down the road,’” Wilson says, her voice rising with emotion. “So, ladies and gentlemen, children of all ages: We’ll see you down the road!”

**********

After nearly 150 years of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey hogging the circus spotlights, you might suppose they were the big bang of it all, but not so. Step right up and I’ll tell you a story of freaks and fantasy and flight and fortunes and a great American capitalistic dream come true. Excuse me, sir, please turn off your iPhone.

The first American circus debuted in Philadelphia, then the nation’s capital, on April 3, 1793. The founder and star was John Bill Ricketts, a dashing Scottish horseman, who would ride a stallion round a ring standing in the saddle, with a 9-year-old boy—also standing—on his shoulders. One of the show’s attractions was a Revolutionary War hero—a horse named Jack once ridden by Gen. George Washington (or so the tale goes), a confirmed circus fan who entrusted the steed to Ricketts for his show.

Soon ragtag troupes were driving wagons through small towns staging “mud shows” in canvas tents, inspired by the productions of their European forebears. Because this was the U.S.A., you had to have a gimmick; and what the American impresarios added was exotic fauna: lions and tigers and bears and other talented wildlife netted along the way.

The golden age of the American circus coincided with the Gilded Age, and one Phineas Taylor Barnum (P.T. for short) was a living emblem of both: a New York City swindler who called himself the “Prince of Humbug” and began his career selling tickets to see a mummified “mermaid” made of a monkey’s head sewn to a fish.

P.T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome filled not one but three tents—and sometimes as many as seven—dividing the audience’s attention among outlandish, phantasmagoric displays. To the lion tamers, clowns and trick riders he added freak shows: human zoos of bearded women and “armless wonders.” When Barnum merged with his competitor, J. A. Bailey, in 1881, they crowned their union the "Greatest Show on Earth.”

By the turn of the century, village schools, mills and shops shuttered for “Circus Day,” and hardscrabble farmers and their children boarded discounted trains to the nearest town center where the tent was raised. For kids seeing camels march down Main Street, “running away with the circus” became a dream—and an option.

The latter was true for five of the Ringling brothers, raised by a harness maker first in Iowa and later Wisconsin. After visiting the circus in 1870, they hand-stitched a rag tent in their backyard, charged a penny admission and earned enough to upgrade to muslin. By the time Barnum & Bailey returned from a six-year European tour in 1902, the Ringling circus was a potential usurper. The brothers had harnessed the same global gymnastics trend that revived the Olympics in 1896. Freaks and geeks were très passé; the Ringlings’ focus was action-oriented fare.

When the rivals coupled up in 1918, the combined show was called the “Big One.” They weren’t bragging: In the 1920s, the Big One had 1,600 performers traveling on four, 100-car trains. It was all fun and fantastical until the Great Depression. Soon afterward, the talkies seduced audiences. There were attempts to modernize: whole shows based on a single theme or orchestrated like complex ballets, including 1942’s Ballet of the Elephants, choreographed by George Balanchine with an original score by Igor Stravinsky.

In the 1970s, the nouveau cirque, groovy one-ring productions influenced by arty affairs from Europe that eschewed sideshows and animal acts, cast the seeds of the renewal blossoming today: smaller operations like the San Francisco-based Pickle Family Circus, with its cooperative structure and ensemble juggling, and the clown-focused Big Apple Circus (which, after shutting down in 2016, announced earlier this year that it would return with new ownership this fall).

In 1984, a band of 20 Québécois street performers led by the fire-breathing, stilt-walking accordionist and high-stakes poker player Guy Laliberté became Cirque du Soleil. Like everything in the ’80s—hair, shoulder pads, attitude—it went big and broad, reinventing spectacle on a grand international scale, with giant tents, lavish costumes and elaborate theatrics combined with awesome acrobatic skill. While Cirque grew into a billion-dollar industry, Ringling dwindled under the pressure of animal rights activists and shrinking ticket sales.

“It was a business model they just couldn’t continue,” says Linda Simon, author of The Greatest Shows on Earth: A History of the Circus. “They kept their ticket prices down, but to mount that kind of extravaganza, how are they going to support their railroad cars and their thousands of employees? And there you have it.”

**********

Inside the lobby of Madison Square Garden, I watch two male hand-balancers in red-and-white- striped leotards and wonder if they know their skintight onesies were first worn by the 19th-century French aerialist Jules Léotard, who created his namesake get-up to fly through the air with the greatest of ease, and without a wedgie. The duo shifts from one circus-sutra position to the next in a show of statuesque strength, as looky-loos and their little-loos drink cocktails and sodas and gobble popcorn and candy.

Chimes beckon all to their seats for the grand spectacular, Circus 1903: The Golden Age of Circus, a new traveling homage to the kind of old-timey show you would have seen more than a century ago, after Barnum & Bailey’s circus returned from its tour of Europe with the crème de la crème of foreign talents in tow.

A mustachioed, top-hatted ringmaster named William Winterbottom Whipsnade (a.k.a. David Williamson, a magician) scans the crowd. “I need a kid with personality!” he booms. Lucky Lucas, 7, gets plucked up. Whipsnade sits on a short stool and asks, “You ragamuffin, you want a good look at the elephants?”

You bet! Whipsnade pulls a balloon from his pocket, blows it up, and twisting it into an elephant says, “I like you, Lucas. You’re weird like me. You’ve got sawdust in those veins!”

This is a big tease. The magical appeal of Circus 1903 is a new breed of pachyderm: hyper-realistic, life-size puppets, by the creators of the Broadway smash War Horse. As Lucas runs off with his prize, Whipsnade scoffs at the light applause: “You’re not at the theater! You’re at the circus!”

Not to be a killjoy, but technically speaking, we’re not at a circus, as circus is Latin for circle. Any Roman will tell you that, and then try to take credit for starting the whole thing in a ring. And while they did innovate the ring, “the real origins of the circus,” says Simon, were “street entertainers in Europe, responding to things in their culture, showing off their talents.”

Which brings us full circle-ish back to here and now and Circus 1903, whose good-natured, kid-friendly shenanigans are presented facing the audience, from a stage. Among the world-class stars: the Sensational Sozonov, balancing on a teeterboard atop sky-high cylinders. The Cycling Cyclone, a “wizard of the wheel” on a bicycle—spinning, rearing, balancing—and doing on a bike what Philip Astley, father of the modern circus, did on a horse at the London opening of Astley’s Amphitheatre, in January 1768.

“Now for the weird and wonderful side of the human species,” Whipsnade bellows. “The sideshow!” He unveils the (faux) Bearded Lady, the (somewhat) Strong Man, and the Man-Eating Chicken: a man...eating chicken. “Now, for the beguilingly bizarre!” The Elastic Dislocationist, an apparently spineless woman from Ethiopia, bends in two, with her buttocks on her head. She stares hypnotically between her legs and proceeds to walk them 180 degrees spiderishly around herself. “Make her stop!” cries a tot next to me.

More bizarre than beguiling, I want to look away, but toward what? Then it hits me. This charming little circus is missing something: an audience on the other side of a ring, their expressions of joy, fear and awe amplifying my own, exciting and uniting all of us. (Gotta give it to the Romans.) I replay the moment for Simon, the historian, who gets it: “That communal experience of everybody being amazed at something, and knowing that everyone else is amazed—that’s lost.”

My grievance is cut short with the grand entrance of the elephant Queenie and her calf Peanut, who elicit a collective gasp and cheers from the crowd. The molded foam-and-fabric-mesh puppets, with their realistic glass eyes, completely capture the lumbering walk, weight and emotion of their wild mates, thanks to the four puppeteers on stilts half-hidden inside Queenie and the one beneath Peanut, precisely manipulating hinged trunks and limbs. Mother teaches child to do circus tricks—stand on a stool, turn in a circle, bow down, each to great, guilt-free applause. PETA would be proud.

But, for me, the real breath-takers are fifth-generation Mexican tightropers Los Lopez, who don’t just walk the wire but jump rope, ride unicycles and bike on it, too—with a bar balanced on their shoulders, while a woman in the middle slides into splits. This lady knows how to put the fun in funambulist.

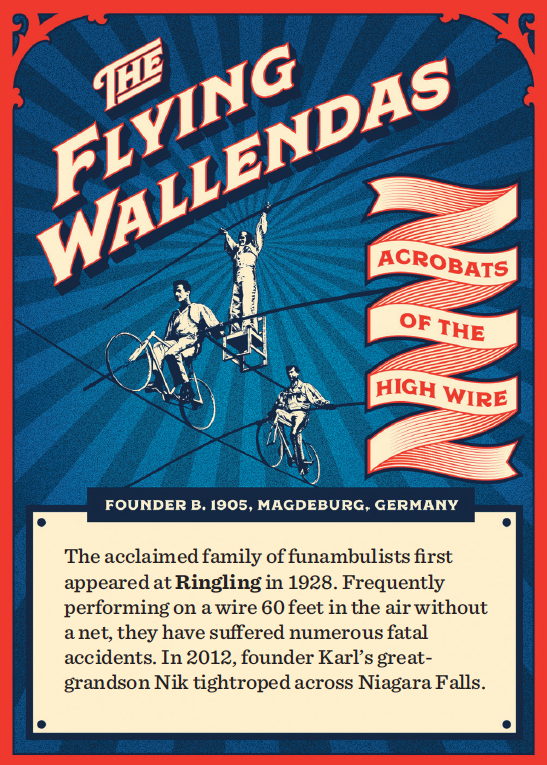

Hey, when it comes to the circus, it takes all kinds. “Life is on the wire,” mused Karl Wallenda, founder of the celebrated circus troupe. “The rest is just waiting.” For most of us, waiting is just fine, as long as we get to watch something worth waiting for. And that, in a circus peanut nutshell, is why the show will go on.

“The future of the circus,” says Simon, “is a combination of different genres—so there’s dance, acrobatics, trapeze, satire, critique, juggling, all of that in a different kind of intimate experience.”

**********

Even so, I would like to file a complaint. More often than not, these newfangled newbies seem to have ditched the very symbol of the circus and its beating emotional heart: the clown. Which brings me to, of all places, Yale.

On an overcast day this spring, students sporting red rubber noses wander around a classroom exhibiting raw bursts of emotion. If you suffer from coulrophobia, you’d be freaking out right now. Then again, if you, like me, have always wanted to say, “I went to Yale,” this class is more fun than skipping school.

Christopher Bayes, Yale School of Drama’s head of physical acting, gives the students vocal cues. “Anxiety!” There’s nail-biting, furrowed brows, hunched shoulders cowering in corners.

At “Anger!” the twenty-somethings look like me on the phone with Time Warner Cable.

“Despair!” They keen, wail, implore heaven; some even really cry.

“I try to get these guys to go primary, expressing without filter,” says Bayes, boyishly handsome in jeans, a gray T-shirt and wire-rimmed glasses. He starts with negative emotions. “Then we can find our way to play—have a Yay! party.” He adds, “It’s not therapy, but it can be therapeutic.”

Which is fitting, as clowns embody the spirit of the circus much as aerialists and acrobats represent its raw physicality. Each imbues the other with meaning, creating a balance. “After watching people fly through the air and do all kinds of death-defying stunts, clowns are something just really human, to make us laugh in a really simple way,” Bayes says. “They draw people further and further into the show in a way that’s much more naive and grounding.”

While the red nose was reportedly inspired by the rubicund honkers of buffoonish boozehounds, a nose is not required. Ancient cultures from Egypt and China to Greece and the American Indians had a version of the clown. Our modern exemplars include Charlie Chaplin, the Marx Brothers, Carol Burnett, Steve Martin and numerous “Saturday Night Live” icons.

Not for nothing, President Nixon, clown lover, signed Proclamation 4071 on August 2, 1971, declaring the first week of August “National Clown Week.” But it wasn’t long after that that the clown’s rep took a hit, thanks in part to John Wayne Gacy Jr., the killer clown in Stephen King’s novel It, and more recently the reports of real-life violent clowns lurking around certain American neighborhoods.

“I think the U.S. is the only place where we have that kind of culture surrounding clowns,” Bayes says. “They don’t have it in Europe. They don’t have Bozo, Krusty, these clowns who laugh for no good reason, who are grotesque, the creepy ones who put on a clown outfit but are not clowns.”

Which means the American clown’s future seems fairly uncertain. Bayes’ students won’t go to the circus, he guesses. “They’re going to be comic actors, some of them; some will make a lot of money, some will struggle. I’m trying to be a kind of infection: to send these beautiful students out into the world to start their own kind of revolution.” He is training them “to ungrow up,” he says, “and welcome back a kind of playfulness as something that has value.”

**********

The morning after my trapeze class, I’m back inside Elizabeth Streb’s SLAM warehouse (a.k.a. Streb Lab for Action Mechanics), where in addition to her trapeze academy she rents warehouse space to practicing professional daring-doers. There’s a girl spinning in aerial silks; guys flipping between trapeze bars; and the Streb Extreme Action company—a troupe of six men and three women equal in size and strength—rehearsing for the company’s show SEA (Singular Extreme Actions).

They launch from a trampoline, flying like synchronized missiles, full- body-planting into a floor mat one after another in hair-raising succession, side by side by side. Like cartoon characters, they incredibly survive impact, spring up, and go again and again: thud, thud, thud, thud. At first, the sound of raining bodies hitting the ground is slightly sickening, but soon it grows into an organic drumbeat, rhythmic and cool.

“Get some air, get some air!” shouts Streb, 67, seated in a metal folding chair a few feet away from the landing pad. “Yes! That’s it! Watch out!”

Streb combs a hand through her thick black punk-rock hair, adjusts her thick black-framed glasses. Dressed in a black suit with gold piping, the pants stuffed into knee-high motorcycle boots, she looks equal parts Goth ringmaster, avant-garde artist and intellectual godmother to the cirque new wave. All of which she is, as well as a 1997 MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Fellow, awarded for her “original approach to choreography that is action oriented and gravity defying.”

“I always tell them, ‘Harder, faster, sooner, higher!’ That’s the mantra,” Streb says. (Moments later, she yells: “Fall slower!”)

Streb has choreographed spectacles of all sizes, including a series of performances during the 2012 Olympic festival, when her troupe made jaw-dropping use of London landmarks: bungee-jumping acrobatics from the Millennium Bridge, “walking” down the side of the City Hall building, and dancing, while tethered, atop the spokes of the massive, revolving London Eye.

Her wild ideas were born in a tent in Rochester, New York, where Streb grew up going to the Shrine Circus every year. “It was my obsession,” she says. “I loved odd things: the smells, the sawdust, the dirtiness, the fact that it was in a tent. It was a magical world. I wanted to be a troubadour like that. I wanted that lifestyle right away. I knew it.”

After studying dance in college (though she’d never taken a dance class), Streb struck out for San Francisco before moving to New York, where her one-woman shows grew into the ensemble of acrobats she calls “action heroes,” who perform net-less, near-death, whimsically freakish physical feats that might incorporate ropes, cinder blocks and an iron beam, or trusses and giant custom-made machines like spinning ladders and wheels.

Ask how her troupe has evolved from the circus, and Streb points to the synchronized fliers, crashing flat-bodied against the floor. “The thing that we do that the other circuses won’t do—and now they’re going to steal my idea—is we land,” she says. “Why does the circus pretend that gravity doesn’t exist? And why do they think that’s beautiful? You’re lying about physicality!”

“In the traditional circus, you do the trick, you pose, you smile, they applaud,” says aerial specialist Bobby Hedglin-Taylor, a Streb instructor and actor who also trains Broadway stars. “Those days are gone. One thing that attracted me to Streb and her work is she doesn’t compete with the circus. She’s made it her own.”

A week later, Streb, dressed in a black suit with a Pac-Man print, looks anxious and excited as she paces before an audience of all ages and every race. An M.C. whips up the crowd: “We encourage you to make noise! Take pictures! Film the show! Post it to social media! Get the word out! And thank you for coming!”

Streb’s action heroes, in their shiny red footless unitards, fly and flip and fall. But an act called “Steel” steals the show. An eight-foot-long, 200-pound I-beam is lowered from the ceiling by a thick chain, and stops a foot from the ground. A performer on each end sends it spinning, the sound of their hands pounding against the metal ringing like a gong, the air from the whirling beam fanning the audience.

One by one, the troupe dodges and rolls under the whirling death girder, sitting up and lying down over and over as the beam misses their heads by mere inches, risking a major dental bill at best and brain scrambling at worst. It’s stomach churning. Half the crowd is watching through splayed fingers.

Afterward, when the show ends, Streb comes over, greets me with a hug and asks if I’ve gone flying lately. No, actually, I say: I threw out my back after dropping my keys and bending over to pick them up. She shakes her head and smiles. “Life is a dangerous game.”

**********

On the subway back to Manhattan, three teens congregate in the middle of the car. One wearing a black baseball cap announces, “Ladies, gentlemen! May we have your attention please! We are not homeless. We do not do drugs. The cops don’t like us because their daughters do.” At this, heads locked on smartphone screens look up, and there’s a chorus of laughter.

A boombox starts playing dance music, and a kid in a New England Patriots T-shirt grabs the parallel poles that run along the subway car’s ceiling and starts flipping and performing perfectly executed tricks and maneuvers. His friends cheer him on and in turn perform spinning stunts on the center passenger pole. Riders slide away to give the flying limbs room. Soon everybody’s encouraging them with “Woo-hoo’s!” and applause.

As the train pulls into the station, it occurs to me that you can always find a circus, and sometimes the circus will find you.

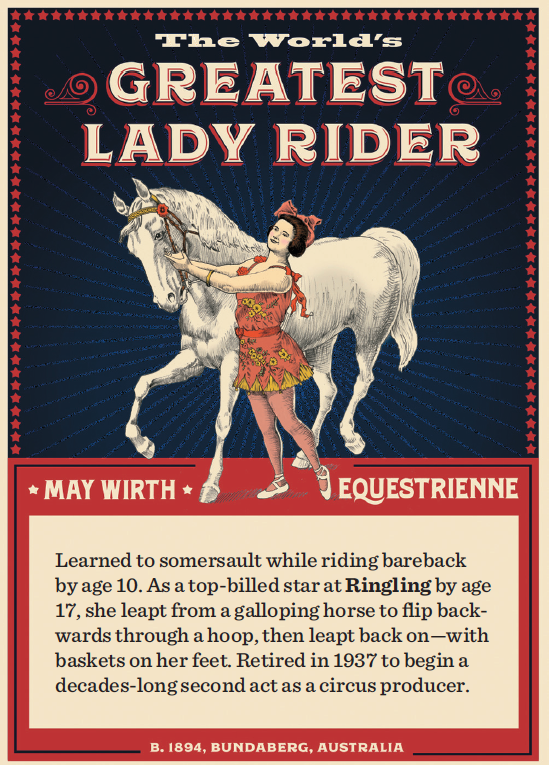

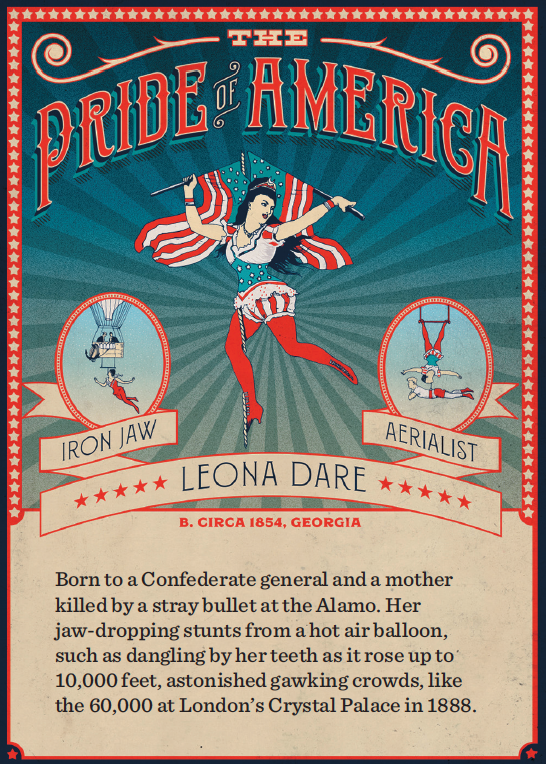

Editor's Note: In “Divas and Daredevils,” we said Leona Dare’s mother was killed by a stray bullet at the Alamo. In fact, her grandmother was killed there.

The Greatest Shows on Earth: A History of the Circus