A New Museum Is Bringing Relics of the Revolutionary War Into Public View for the First Time in Decades

Scheduled to open next year in Philadelphia, the museum will immerse visitors into the time when the American colonies became the United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/47/b1479a0b-3a25-4348-b456-77ea352a2c9b/exterior_rendering.jpg)

In a nondescript warehouse mere miles from Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, where George Washington hunkered down for the winter of 1777, long-forgotten pieces of the Revolutionary War are preparing to emerge from a decades-long slumber.

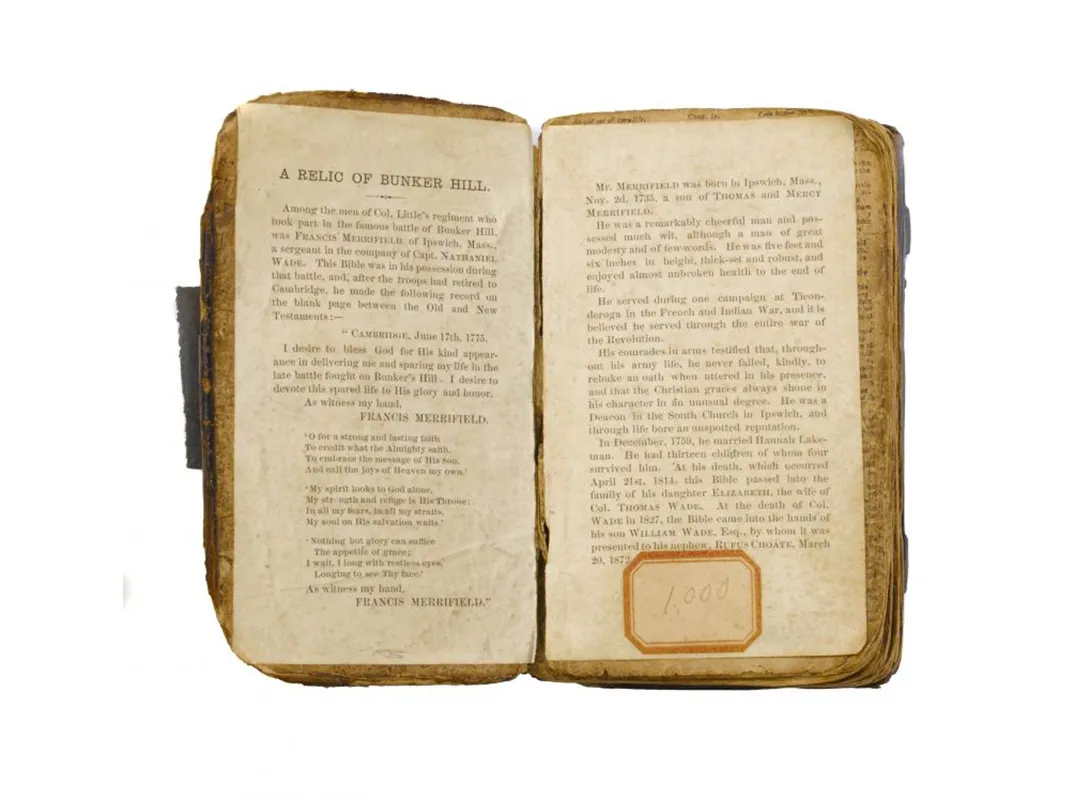

When I visit the preservation facility hidden in a bland office park one afternoon in May, history is virtually spilling off the shelves. The Museum of the American Revolution’s 3,000-piece collection of rarely seen artifacts and documents is in the process of traveling to a new facility in the heart of Philadelphia. On one table rests a pair of faded leather epaulettes, the only set worn by an non-commissioned officer in the Continental Army known to exist and thought to have been presented by French General Lafayette to American soldiers under his command. A pair of red booties, made from the pilfered coat of a British footsoldier, belonged to Sgt. James Davenport, a Massachusetts native who lost two brothers in the fight for independence. One of the more recent acquisitions to the collection is a small King James Bible carried at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775 by Francis Merrifield, a Continental sergeant who inscribed plaudits to God between verses of the Old Testament after returning home from battle with famed Colonel Moses Little ‘all bespattered with blood.’

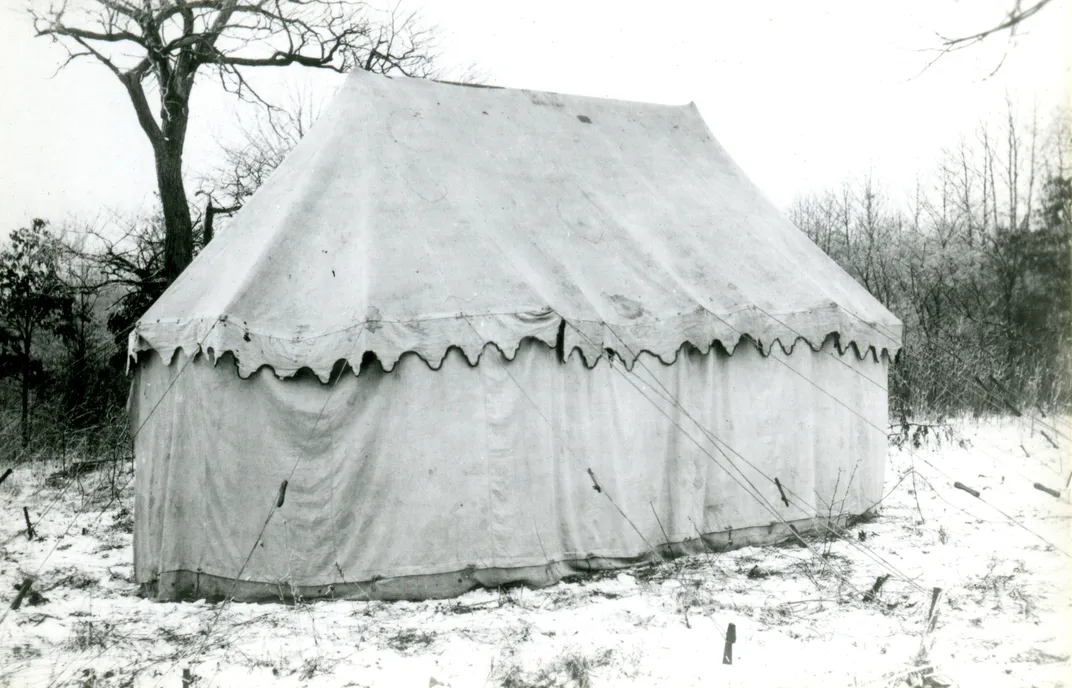

The heart and soul of the collection, as it was for the Continental Army, is Washington’s headquarters tent, the faded canvas that housed the founding father during the army’s difficult winter at Valley Forge. The tent will be the center of the permanent collection when the museum opens its doors next year on April 19. The tent will live in a 300-square-foot object case, the second-largest in the country; the largest contains the original Star-Spangled Banner at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Of the museum’s permanent collection, hundreds of artifacts haven’t been seen to the public in almost 80 years, if ever.

“We’re something like a 100-year-old start-up,” R. Scott Stephenson, the museum’s vice president of collections, exhibitions and programming, tells Smithsonian.com, describing the museum’s now decades-long effort to catalogue and curate the warehouse of hidden treasures the institutions inherited from the Valley Forge Historical Society in the early 2000s. “We’re still trying to figure how exactly some of these items ended up here.” (The society still exists, but shifted away from collecting.)

This secret reliquary to the Revolutionary War would not even exist were it not for the strange and litigious journey of the Washington headquarters tent. While George Washington never had a child, Martha Washington did, with Daniel Parke Custis, who she was married to until his death in 1757. Washington’s headquarters tent remained in the Custis family’s possession until the end of the Civil War, when it was confiscated from Confederate general Robert E. Lee and wife Mary Anna Custis Lee, a great-grandaughter of Martha Washington. The tent remained in federal custody for 40 years, occasionally displayed on the grounds of the Smithsonian, until Lee’s eldest daughter Mary successfully sued the government over its ownership at the turn of the century.

It was Reverend W. Herbert Burk who planted the seeds of the modern museum when he purchased the tent from the younger Mary Custis Lee in 1909 for $5,000 as she raised money for a Confederate widow’s home. Burk, an Episcopal minister in Valley Forge, was an aspiring historian and avid collector, and his informal collection of Revolutionary War artifacts were the core of what at the time was referred to as the Valley Forge Museum of American History (and, later, the Valley Forge Historical Society). While members of the society had discussed a vision of a more official museum in the years before Burk’s death in 1933, they quietly amassed a sprawling collection in anonymous warehouses for decades, farmed out to other institutions over the years but otherwise living in limbo, forgotten in a nondescript facility in central Pennsylvania.

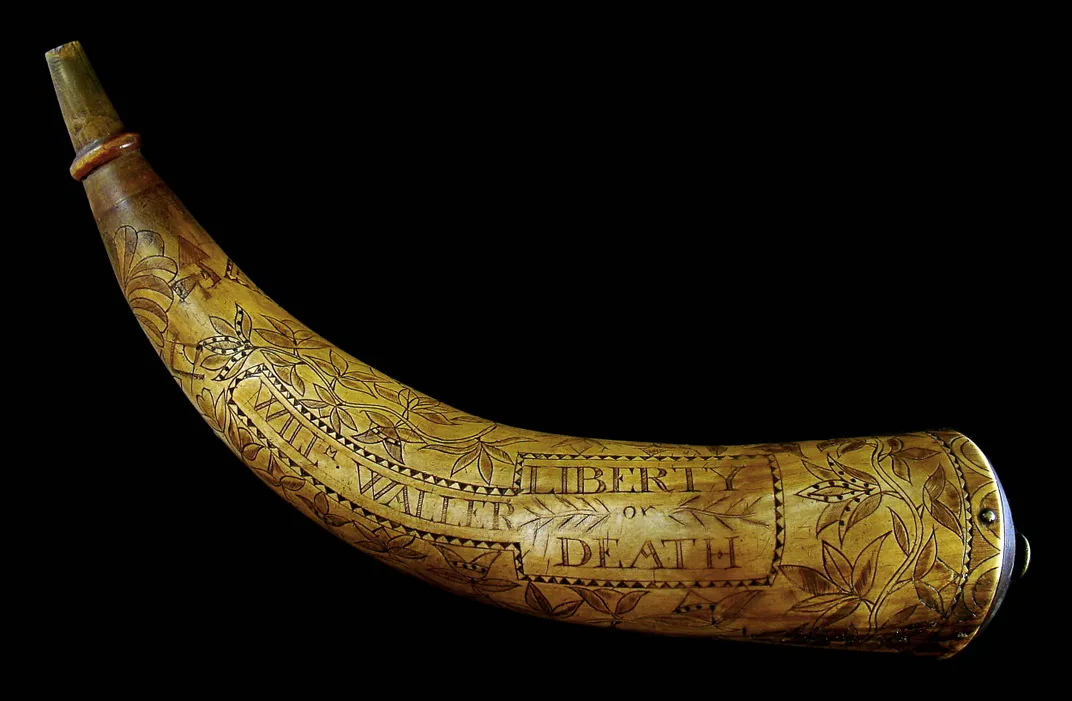

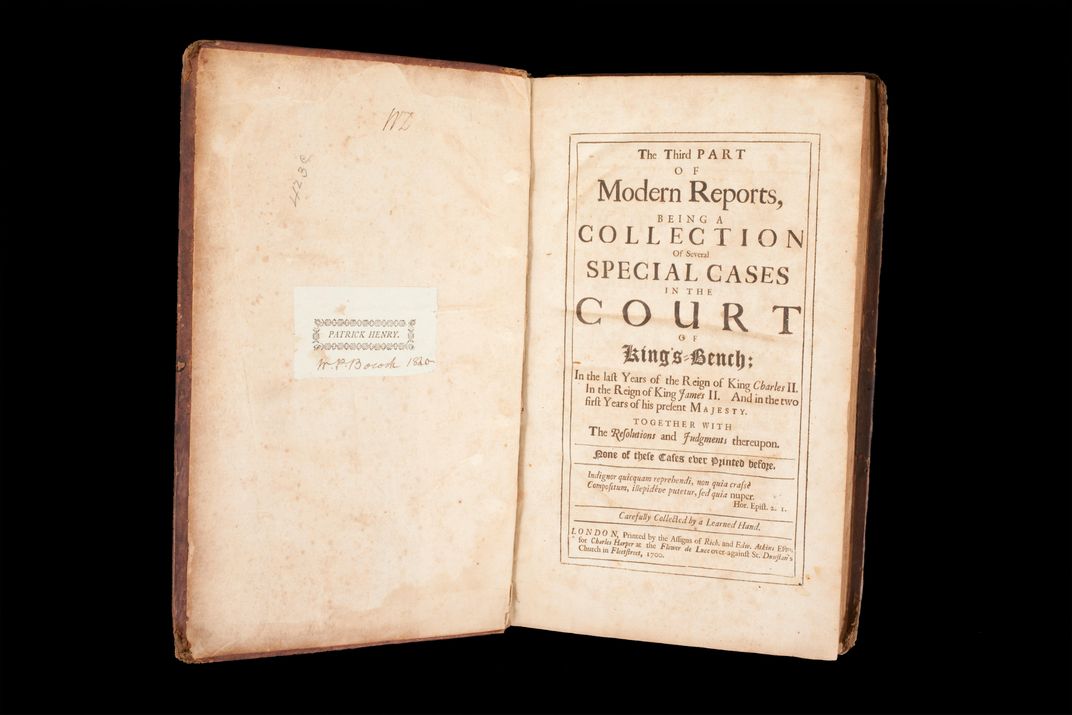

According to the curators, the collection’s standout pieces tend to highlight untold aspects of the war. A pair of gold medals were likely worn at the battles of Lexington and Concord — by loyalists fighting for the King's Orange Ranger, an infantry battalion based out of Orange County, New York. A set of camp cups forged from Spanish dollars by Philadelphia silversmith Edward Milne were likely bestowed upon Washington two days before his march through the city in the waning days of August 1777. And a decaying July 6, 1776, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post contains the best buried lede in American history: below the classifieds and local government minutes, the first public English-language declaration by the Continental Congress of the U.S. as “free and independent states.” Even a beer mug from 1773 still carries the faint scent of rum and sugar. “You can smell the revolution,” says Stephenson.

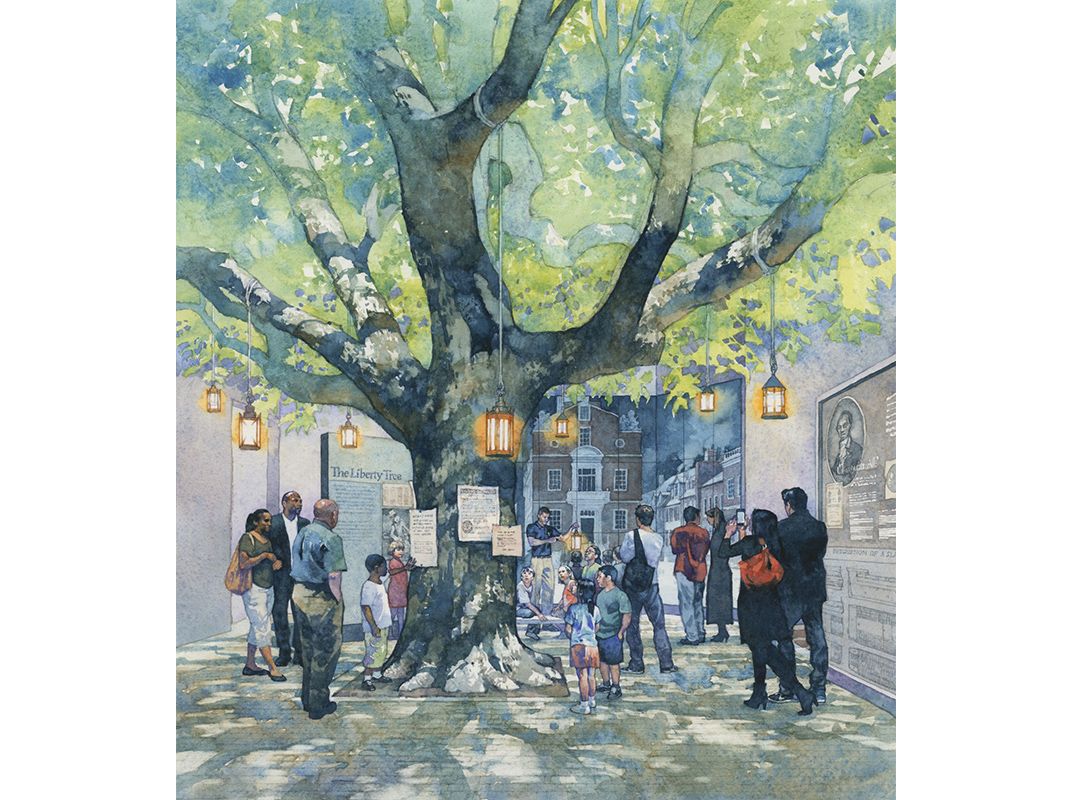

Just two blocks from Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the museum will present the first deep, complete examination of the Revolution’s turbulent history. In turn, the museum’s role is to serve as a “portal” to the city’s other colonial-era sites for tourists who may only glimpse one facet of the Revolution during their visits to the Liberty Bell, the National Constitution Center and other noteworthy sites along Independence Mall. Borrowing from more modern exhibits, the construction focuses on creating an immersive recreation of the events surrounding the adoption of the Declaration of Independence and colonies’ long campaign against the British. Sprawling screens and a specially engineered “video-sound environment” will move visitors from the coronation of King George III to the signing of the Declaration of Independence to the front lines of battle.

“We want you to feel like you could have been part of the Revolution,” museum president Michael Quinn tells Smithsonian.com. “We want you to feel like you’re actually standing under the Tree of Liberty in Boston, or debating the Declaration of Independence.”

But the goal isn’t just to provide visitors with artifacts from the Revolution or wow them with immersive technology, but to uncover the hidden stories and voices of the fight for independence as well. While the average American schoolchild absorbs the most cursory hagiography of the founders and the ragtag guerilla warriors of the Continental Army (whose hit-and-run tactics, according to Stephenson, are greatly exaggerated), the museum’s goal is to provide a historically honest and visually provocative depiction of the turbulent struggle for independence, a tick-tock of the bloody conflict rich with details meant to capture the imagination of visitors. One vignette will insert visitors into an encounter between two brothers between battles as Washington’s army fled New York for Philadelphia in 1776. Portrayed by reenactors and devastated from combat, the two barely recognize each other, an effort to dramatize the suffering of Washington’s army before their hibernation in Valley Forge.

“We want to tell a deeper story,” says Quinn.

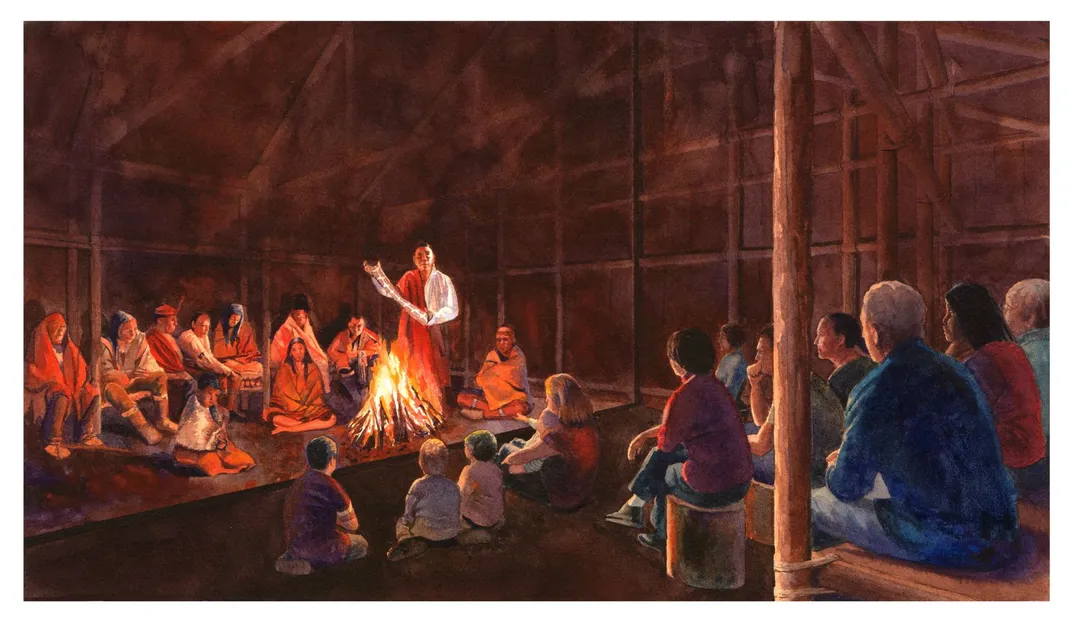

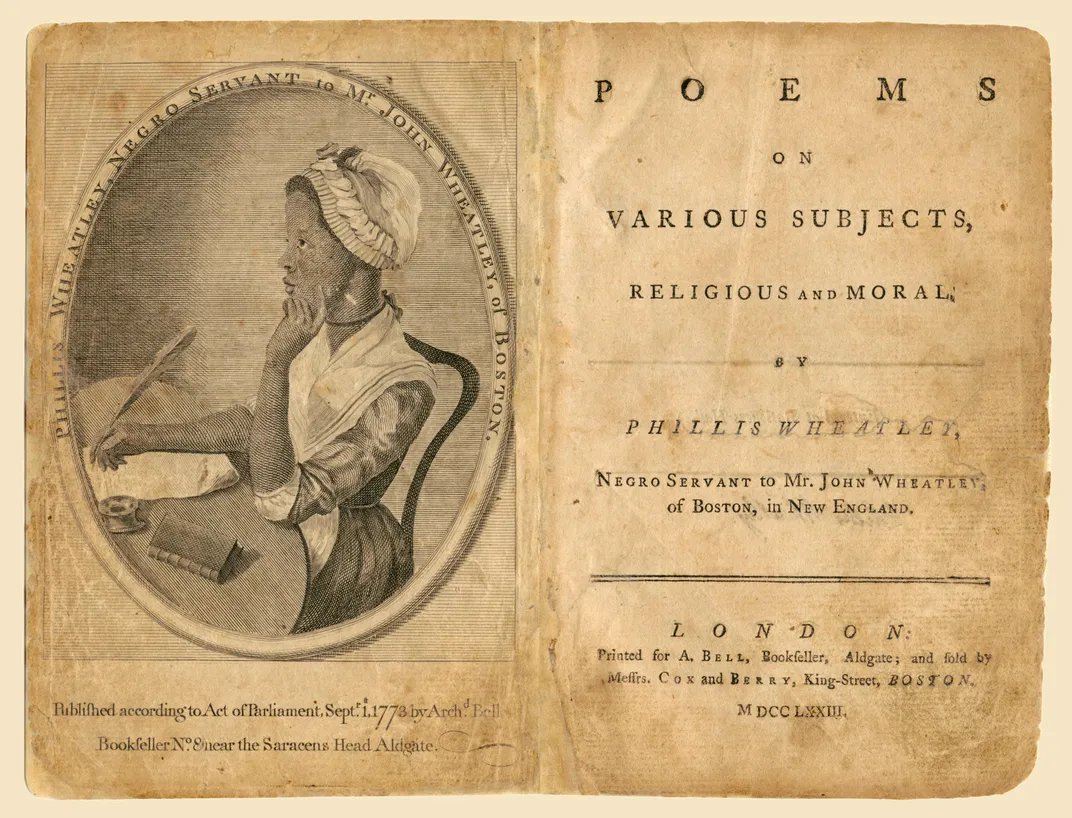

Telling that deeper story means incorporating more voices, and the museum has actively sought to incorporate the experiences of African-Americans and Native Americans in the run up to the war between their European overlords. One exhibit places visitors into the middle of a debate between Oneida Nation leaders over being drawn into the war, a scene Quinn lauds as “comparable to Independence Hall.” Another vignette portrays the life of James Forten, a 14-year-old runaway slave who became a crewman aboard the privateers that formed the backbone of the colonies’ sea campaign against the Royal Navy.

“We’ve made a concerted effort to highlight the experiences of blacks, women, and Native Americans,” says Quinn. “We can’t have a nuanced examination of the revolution without them.”

That the museum has been able to afford its preservation and construction efforts is itself impressive: the 118,000 square foot space is projected to cost a whopping $150 million to complete, and the museum hopes to develop a $25 million endowment. As of June, the museum has raised $130 million of its goal thanks to generous donations from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Oneida Indian Nation, and a slew of private individuals and foundations.

For the preservationists and curators who have spent years toiling over the hidden treasures of America’s baptism by fire, it’s a historical undertaking well worth the investment. Even the excavation of the museum’s site in Philadelphia yielded more than 82,000 artifact pieces from the city’s formative years and development since its earliest development. “For us, the best outcome of a tourist’s visit is that they’ll decide to read a book,” Quinn said.

For the likes of Quinn and Stephenson, the museum’s opening in 2017 will mark not just the end of almost two decades of the institution’s development, but the culmination of a century of waiting for the descendants of the Washington family. In an August 1906 edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Bulletin marking her sale of Washington’s tent to Burk, Mary Custis Lee stated that “there is no place at which I should rather see at least one of the tents than in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, beside the Liberty Bell and its other historic relics.” Thanks to a small, dedicated group of historians and preservations, Lee may finally get her wish.