Secrets of the Colosseum

A German archaeologist has finally deciphered the Roman amphitheater’s amazing underground labyrinth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Colosseum-Secrets-Hypogeum-631.jpg)

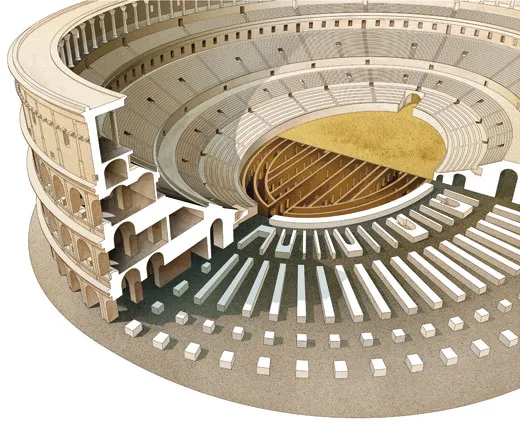

The floor of the colosseum, where you might expect to see a smooth ellipse of sand, is instead a bewildering array of masonry walls shaped in concentric rings, whorls and chambers, like a huge thumbprint. The confusion is compounded as you descend a long stairway at the eastern end of the stadium and enter ruins that were hidden beneath a wooden floor during the nearly five centuries the arena was in use, beginning with its inauguration in A.D. 80. Weeds grow waist-high between flagstones; caper and fig trees sprout from dank walls, which are a patchwork of travertine slabs, tufa blocks and brickwork. The walls and the floor bear numerous slots, grooves and abrasions, obviously made with great care, but for purposes that you can only guess.

The guesswork ends when you meet Heinz-Jürgen Beste of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, the leading authority on the hypogeum, the extraordinary, long-neglected ruins beneath the Colosseum floor. Beste has spent much of the past 14 years deciphering the hypogeum—from the Greek word for “underground”—and this past September I stood with him in the heart of the great labyrinth.

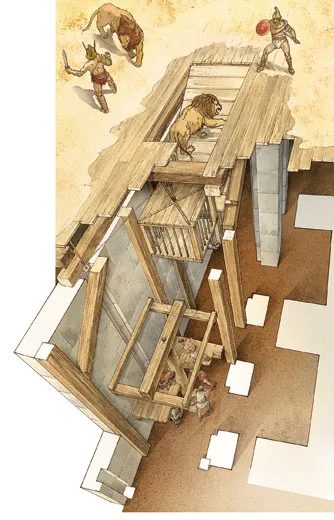

“See where a semicircular slice has been chipped out of the wall?” he said, resting a hand on the brickwork. The groove, he added, created room for the four arms of a cross-shaped, vertical winch called a capstan, which men would push as they walked in a circle. The capstan post rested in a hole that Beste indicated with his toe. “A team of workmen at the capstan could raise a cage with a bear, leopard or lion inside into position just below the level of the arena. Nothing bigger than a lion would have fit.” He pointed out a diagonal slot angling down from the top of the wall to where the cage would have hung. “A wooden ramp slid into that slot, allowing the animal to climb from the cage straight into the arena,” he said.

Just then, a workman walked above our heads, across a section of the arena floor that Colosseum officials reconstructed a decade ago to give some sense of how the stadium looked in its heyday, when gladiators fought to their death for the public’s entertainment. The footfalls were surprisingly loud. Beste glanced up, then smiled. “Can you imagine how a few elephants must have sounded?”

Today, many people can imagine this for themselves. Following a $1.4 million renovation project, the hypogeum was opened to the public this past October.

Trained as an architect specializing in historic buildings and knowledgeable about Greek and Roman archaeology, Beste might be best described as a forensic engineer. Reconstructing the complex machinery that once existed under the Colosseum floor by examining the hypogeum’s skeletal remains, he has demonstrated the system’s creativity and precision, as well as its central role in the grandiose spectacles of imperial Rome.

When Beste and a team of German and Italian archaeolgists first began exploring the hypogeum, in 1996, he was baffled by the intricacy and sheer size of its structures: “I understood why this site had never been properly analyzed before then. Its complexity was downright horrifying.”

The disarray reflected some 1,500 years of neglect and haphazard construction projects, layered one upon another. After the last gladiatorial spectacles were held in the sixth century, Romans quarried stones from the Colosseum, which slowly succumbed to earthquakes and gravity. Down through the centuries, people filled the hypogeum with dirt and rubble, planted vegetable gardens, stored hay and dumped animal dung. In the amphitheater above, the enormous vaulted passages sheltered cobblers, blacksmiths, priests, glue-makers and money-changers, not to mention a fortress of the Frangipane, 12th-century warlords. By then, local legends and pilgrim guidebooks described the crumbling ring of the amphitheater’s walls as a former temple to the sun. Necromancers went there at night to summon demons.

In the late 16th century, Pope Sixtus V, the builder of Renaissance Rome, tried to transform the Colosseum into a wool factory, with workshops on the arena floor and living quarters in the upper stories. But owing to the tremendous cost, the project was abandoned after he died in 1590.

In the years that followed, the Colosseum became a popular destination for botanists due to the variety of plant life that had taken root among the ruins. As early as 1643, naturalists began compiling detailed catalogs of the flora, listing 337 different species.

By the early 19th century, the hypogeum’s floor lay buried under some 40 feet of earth, and all memory of its function—or even its existence—had been obliterated. In 1813 and 1874, archaeological excavations attempting to reach it were stymied by flooding groundwater. Finally, under Benito Mussolini’s glorification of Classical Rome in the 1930s, workers cleared the hypogeum of earth for good.

Beste and his colleagues spent four years using measuring tapes, plumb lines, spirit levels and generous quantities of paper and pencils to produce technical drawings of the entire hypogeum. “Today we’d probably use a laser scanner for this work, but if we did, we’d miss the fuller understanding that old-fashioned draftsmanship with pencil and paper gives you,” Beste says. “When you do this slow, stubborn drawing, you’re so focused that what you see goes deep into the brain. Gradually, as you work, the image of how things were takes shape in your subconscious.”

Unraveling the site’s tangled history, Beste identified four major building phases and numerous modifications over nearly 400 years of continuous use. Colosseum architects made some changes to allow new methods of stagecraft. Other changes were accidental; a fire sparked by lightning in A.D. 217 gutted the stadium and sent huge blocks of travertine plunging into the hypogeum. Beste also began to decipher the odd marks and incisions in the masonry, having had a solid grounding in Roman mechanical engineering from excavations in southern Italy, where he learned about catapults and other Roman war machines. He also studied the cranes that the Romans used to move large objects, such as 18-foot-tall marble blocks.

By applying his knowledge to eyewitness accounts of the Colosseum’s games, Beste was able to engage in some deductive reverse engineering. Paired vertical channels that he found in certain walls, for example, seemed likely to be tracks for guiding cages or other compartments between the hypogeum and the arena. He’d been working at the site for about a year before he realized that the distinctive semicircular slices in the walls near the vertical channels were likely made to leave space for the revolving bars of large capstans that powered the lifting and lowering of cages and platforms. Then other archaeological elements fell into place, such as the holes in the floor, some with smooth bronze collars, for the capstan shafts, and the diagonal indentations for ramps. There were also square mortises that had held horizontal beams, which supported both the capstans and the flooring between the upper and lower stories of the hypogeum.

To test his ideas, Beste built three scale models. “We made them with the same materials that children use in kindergarten—toothpicks, cardboard, paste, tracing paper,” he says. “But our measurements were precise, and the models helped us to understand how these lifts actually worked.” Sure enough, all the pieces meshed into a compact, powerful elevator system, capable of quickly delivering wild beasts, scenery and equipment into the arena. At the peak of its operation, he concluded, the hypogeum contained 60 capstans, each two stories tall and turned by four men per level. Forty of these capstans lifted animal cages throughout the arena, while the remaining 20 were used to raise scenery sitting on hinged platforms measuring 12 by 15 feet.

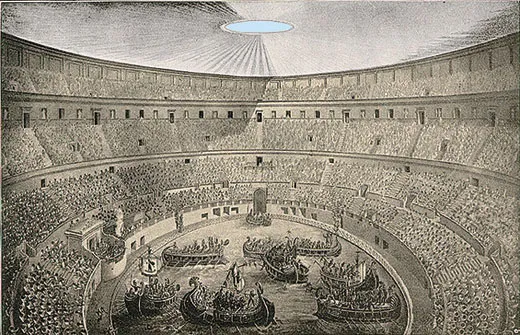

Beste also identified 28 smaller platforms (roughly 3 by 3 feet) around the outer rim of the arena—also used for scenery—that were operated through a system of cables, ramps, hoists and counterweights. He even discovered traces of runoff canals that he believes were used to drain the Colosseum after it was flooded from a nearby aqueduct, in order to stage naumachiae, or mock sea battles. The Romans re-enacted these naval engagements with scaled-down warships maneuvering in water three to five feet deep. To create this artificial lake, Colosseum stagehands first removed the arena floor and its underlying wood supports—vertical posts and horizontal beams that left imprints still visible in the retaining wall around the arena floor. (The soggy spectacles ended in the late first century A.D., when the Romans replaced the wood supports with masonry walls, making flood- ing the arena impossible.)

Beste says the hypogeum itself had a lot in common with a huge sailing ship. The underground staging area had “countless ropes, pulleys and other wood and metal mechanisms housed in very limited space, all requiring endless training and drilling to run smoothly during a show. Like a ship, too, everything could be disassembled and stored neatly away when it was not being used.” All that ingenuity served a single purpose: to delight spectators and ensure the success of shows that both celebrated and embodied the grandeur of Rome.

Beyond the thin wooden floor that separated the dark, stifling hypogeum from the airy stadium above, the crowd of 50,000 Roman citizens sat according to their place in the social hierarchy, ranging from slaves and women in the upper bleachers to senators and vestal virgins—priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth—around the arena floor. A place of honor was reserved for the editor, the person who organized and paid for the games. Often the editor was the emperor himself, who sat in the imperial box at the center of the long northern curve of the stadium, where his every reaction was scrutinized by the audience.

The official spectacle, known as the munus iustum atque legitimum (“a proper and legitimate gladiator show”), began, like many public events in Classical Rome, with a splendid morning procession, the pompa. It was led by the editor’s standard-bearers and typically featured trumpeters, performers, fighters, priests, nobles and carriages bearing effigies of the gods. (Disappointingly, gladiators appear not to have addressed the emperor with the legendary phrase, “We who are about to die salute you,” which is mentioned in conjunction with only one spectacle—a naval battle held on a lake east of Rome in A.D. 52—and was probably a bit of inspired improvisation rather than a standard address.)

The first major phase of the games was the venatio, or wild beast hunt, which occupied most of the morning: creatures from across the empire appeared in the arena, sometimes as part of a bloodless parade, more often to be slaughtered. They might be pitted against each other in savage fights or dispatched by venatores (highly trained hunters) wearing light body armor and carrying long spears. Literary and epigraphic accounts of these spectacles dwell on the exotic menagerie involved, including African herbivores such as elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses and giraffes, bears and elk from the northern forests, as well as strange creatures like onagers, ostriches and cranes. Most popular of all were the leopards, lions and tigers—the dentatae (toothed ones) or bestiae africanae (African beasts)—whose leaping abilities necessitated that spectators be shielded by barriers, some apparently fitted with ivory rollers to prevent agitated cats from climbing. The number of animals displayed and butchered in an upscale venatio is astonishing: during the series of games held to inaugurate the Colosseum, in A.D. 80, the emperor Titus offered up 9,000 animals. Less than 30 years later, during the games in which the emperor Trajan celebrated his conquest of the Dacians (the ancestors of the Romanians), some 11,000 animals were slaughtered.

The hypogeum played a vital role in these staged hunts, allowing animals and hunters to enter the arena in countless ways. Eyewitnesses describe how animals appeared suddenly from below, as if by magic, sometimes apparently launched high into the air. “The hypogeum allowed the organizers of the games to create surprises and build suspense,” Beste says. “A hunter in the arena wouldn’t know where the next lion would appear, or whether two or three lions might emerge instead of just one.” This uncertainty could be exploited for comic effect. Emperor Gallienus punished a merchant who had swindled the empress, selling her glass jewels instead of authentic ones, by setting him in the arena to face a ferocious lion. When the cage opened, however, a chicken walked out, to the delight of the crowd. Gallienus then told the herald to proclaim: “He practiced deceit and then had it practiced on him.” The emperor let the jeweler go home.

During the intermezzos between hunts, spectators were treated to a range of sensory delights. Handsome stewards passed through the crowd carrying trays of cakes, pastries, dates and other sweetmeats, and generous cups of wine. Snacks also fell from the sky as abundantly as hail, one observer noted, along with wooden balls containing tokens for prizes—food, money or even the title to an apartment—which sometimes set off violent scuffles among spectators struggling to grab them. On hot days, the audience might enjoy sparsiones (“sprinklings”), mist scented with balsam or saffron, or the shade of the vela, an enormous cloth awning drawn over the Colosseum roof by sailors from the Roman naval headquarters at Misenum, near Naples.

No such relief was provided for those working in the hypogeum. “It was as hot as a boiler room in the summer, humid and cold in winter, and filled all year round with strong smells, from the smoke, the sweating workmen packed in the narrow corridors, the reek of the wild animals,” says Beste. “The noise was overwhelming—creaking machinery, people shouting and animals growling, the signals made by organs, horns or drums to coordinate the complex series of tasks people had to carry out, and, of course, the din of the fighting going on just overhead, with the roaring crowd.”

At the ludi meridiani, or midday games, criminals, barbarians, prisoners of war and other unfortunates, called damnati, or “condemned,” were executed. (Despite numerous accounts of saints’ lives written in the Renaissance and later, there is no reliable evidence that Christians were killed in the Colosseum for their faith.) Some damnati were released in the arena to be slaughtered by fierce animals such as lions, and some were forced to fight one another with swords. Others were dispatched in what a modern scholar has called “fatal charades,” executions staged to resemble scenes from mythology. The Roman poet Martial, who attended the inaugural games, describes a criminal dressed as Orpheus playing a lyre amid wild animals; a bear ripped him apart. Another suffered the fate of Hercules, who burned to death before becoming a god.

Here, too, the hypogeum’s powerful lifts, hidden ramps and other mechanisms were critical to the illusion-making. “Rocks have crept along,” Martial wrote, “and, marvelous sight! A wood, such as the grove of the Hesperides [nymphs who guarded the mythical golden apples] is believed to have been, has run.”

Following the executions came the main event: the gladiators. While attendants prepared the ritual whips, fire and rods to punish poor or unwilling fighters, the combatants warmed up until the editor gave the signal for the actual battle to begin. Some gladiators belonged to specific classes, each with its own equipment, fighting style and traditional opponents. For example, the retiarius (or “net man”) with his heavy net, trident and dagger often fought against a secutor (“follower”) wielding a sword and wearing a helmet with a face mask that left only his eyes exposed.

Contestants adhered to rules enforced by a referee; if a warrior conceded defeat, typically by raising his left index finger, his fate was decided by the editor, with the vociferous help of the crowd, who shouted “Missus!” (“Dismissal!”) at those who had fought bravely, and “Iugula, verbera, ure!” (“Slit his throat, beat, burn!”) at those they thought deserved death. Gladiators who received a literal thumbs down were expected to take a finishing blow from their opponents unflinchingly. The winning gladiator collected prizes that might include a palm of victory, cash and a crown for special valor. Because the emperor himself was often the host of the games, everything had to run smoothly. The Roman historian and biographer Suetonius wrote that if technicians botched a spectacle, the emperor Claudius might send them into the arena: “[He] would for trivial and hasty reasons match others, even of the carpenters, the assistants and men of that class, if any automatic device or pageant, or anything else of the kind, had not worked well.” Or, as Beste puts it, “The emperor threw this big party, and wanted the catering to go smoothly. If it did not, the caterers sometimes had to pay the price.”

To spectators, the stadium was a microcosm of the empire, and its games a re-enactment of their foundation myths. The killed wild animals symbolized how Rome had conquered wild, far-flung lands and subjugated Nature itself. The executions dramatized the remorseless force of justice that annihilated enemies of the state. The gladiator embodied the cardinal Roman quality of virtus, or manliness, whether as victor or as vanquished awaiting the deathblow with Stoic dignity. “We know that it was horrible,” says Mary Beard, a classical historian at Cambridge University, “but at the same time people were watching myth re-enacted in a way that was vivid, in your face and terribly affecting. This was theater, cinema, illusion and reality, all bound into one.”

Tom Mueller’s next book, on the history of olive oil, will be published this fall. Photographer Dave Yoder is based in Milan.