See Jewish Life Before the Holocaust Through a Newly Released Digital Archive

Roman Vishniac’s extensive work, now open to the public, is ready for some crowd-sourced historical detective work

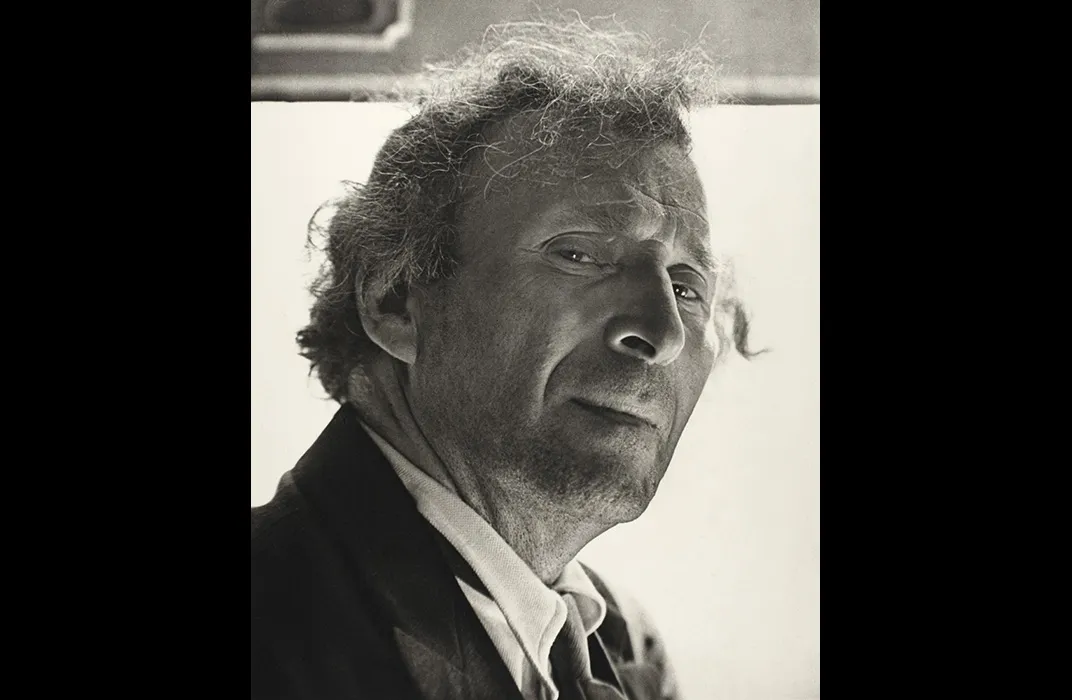

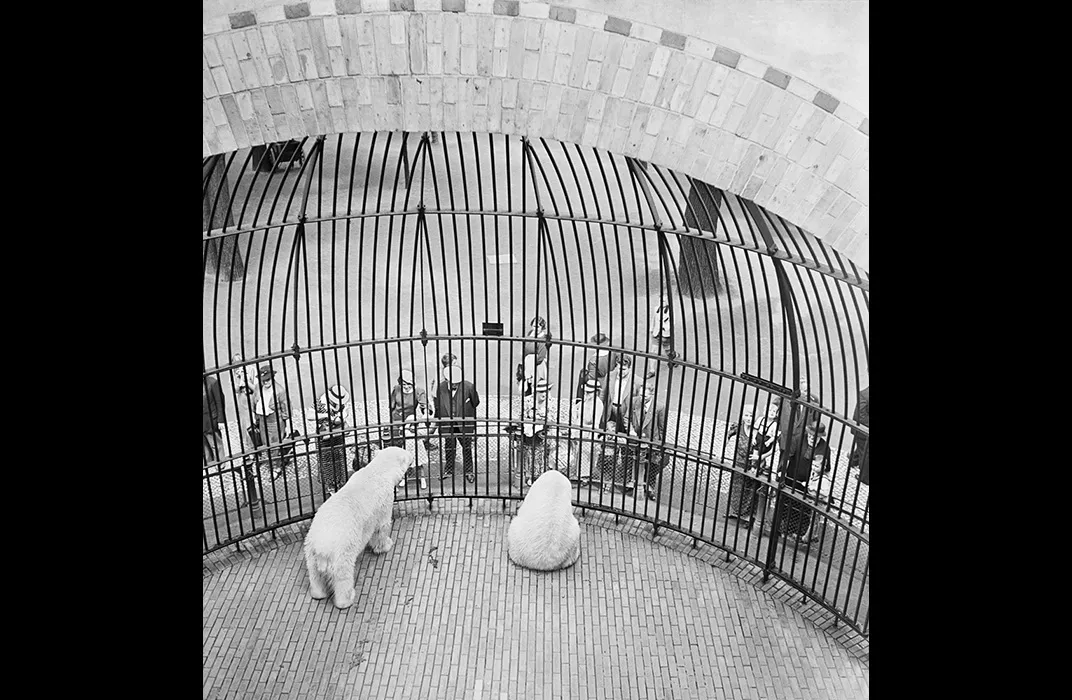

In 1935, Roman Vishniac, a Russian-born Jew and heralded photographer, journeyed throughout Eastern Europe with one goal: photograph impoverished Jewish communities. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, his employer, planned to use the images to raise funds for relief efforts, but the photos would become an iconic link to the culture that vanished as a result of the Holocaust.

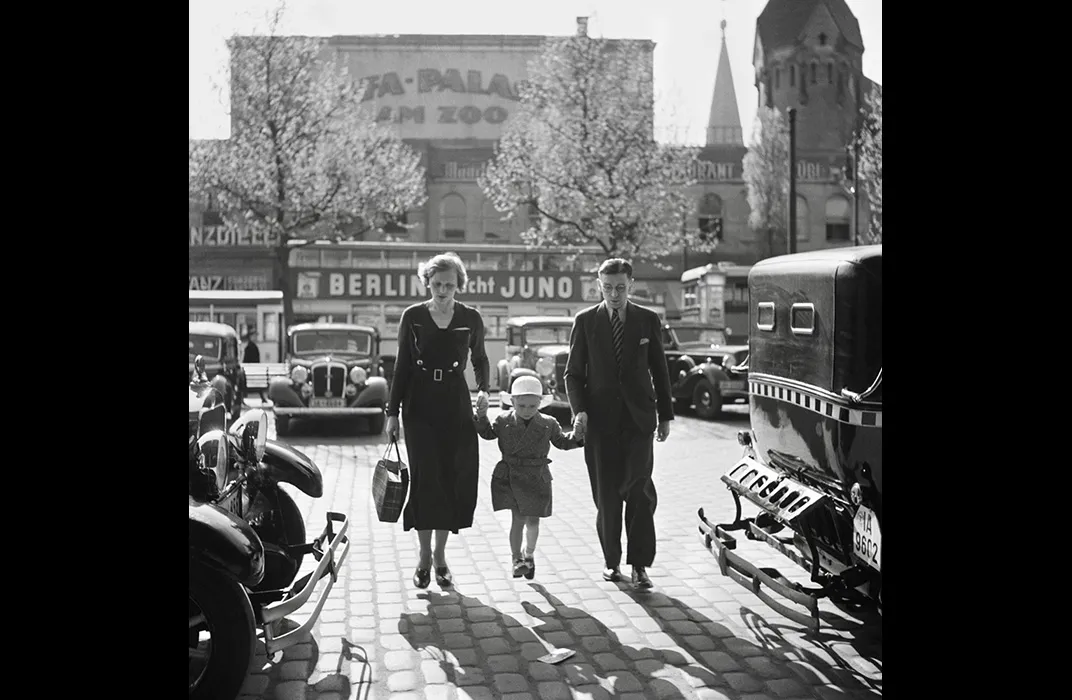

Years earlier, long before his trip through Eastern Europe, Vishniac and his family emigrated from Russia to Berlin, where he built a photo-processing laboratory, pursued his interest in microscopic research, and became an acclaimed street photographer. As Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power in the 1930s, Vishniac remained in Berlin, but after Kristallnacht in 1938, he initiated plans to leave Germany with his family. In 1939, he spent six weeks in an internment camp in France, ultimately managing to secure release and moving with his family to New York City. After the war, he returned to photograph Jewish communities in displaced persons camps in the late 1940s, as well as those in 1950s New York City. Only 350 of Vishniac’s images were published or printed during his lifetime, though his photo archive of negatives numbers around 9,000.

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and the International Center for Photography (ICP) have teamed up to make the rest of Vishniac’s images available to the public. Last week, they launched an online photo database that includes scans of Vishniac’s prints and negatives—in many cases published for the first time anywhere. “This is an incredibly important body of material. He has this iconic role in Jewish culture, and yet only a handful of his images have been printed or published in his lifetime,” says Maya Benton, who curates the archive for ICP and is working on a book on Vishniac’s work.

Most of Vishniac’s negatives and printed images lack captions, and information about what’s on each roll of film is sparse. “We don’t have captions or dates or locations for 99 percent of his work," says Benton. The goal is that by opening the archive up to the public someone, somewhere might recognize something. “We’re in the decade in which Holocaust survivors are dying out, which is why we felt this urgency and this rush to do this,” says Benton.

As people look through the collection, they can make notes on different images, which then go to historians at USHMM to follow up. Searching their own extensive textual and photographic archives, they can track down a name or location clue to the larger context of an image. “It’s more than identifying a person who may have died. It’s about restoring and preserving their history,” says Judy Cohen, director of photographic reference collection at the USHMM. Given the museum’s wide audience and slew of daily visitors, they’ve already had some success in tracking down the individuals even before the project’s launch.

Benton has some personal perspective on the project: Her mother spent her childhood in a displaced persons camp. She’s been studying Vishniac’s work for at least a decade. In the course of her analysis, Benton realized that he actually photographed the camp where her mother lived, giving Benton the opportunity to show some images of the camp to her mother. “She remembered the kind of feel of the place,” recalls Benton, who hopes that the archive provokes similar experiences in Jewish households around the world: Younger, digital-savvy grandchildren sitting down with their parents and grandparents to revisit a world that was lost.

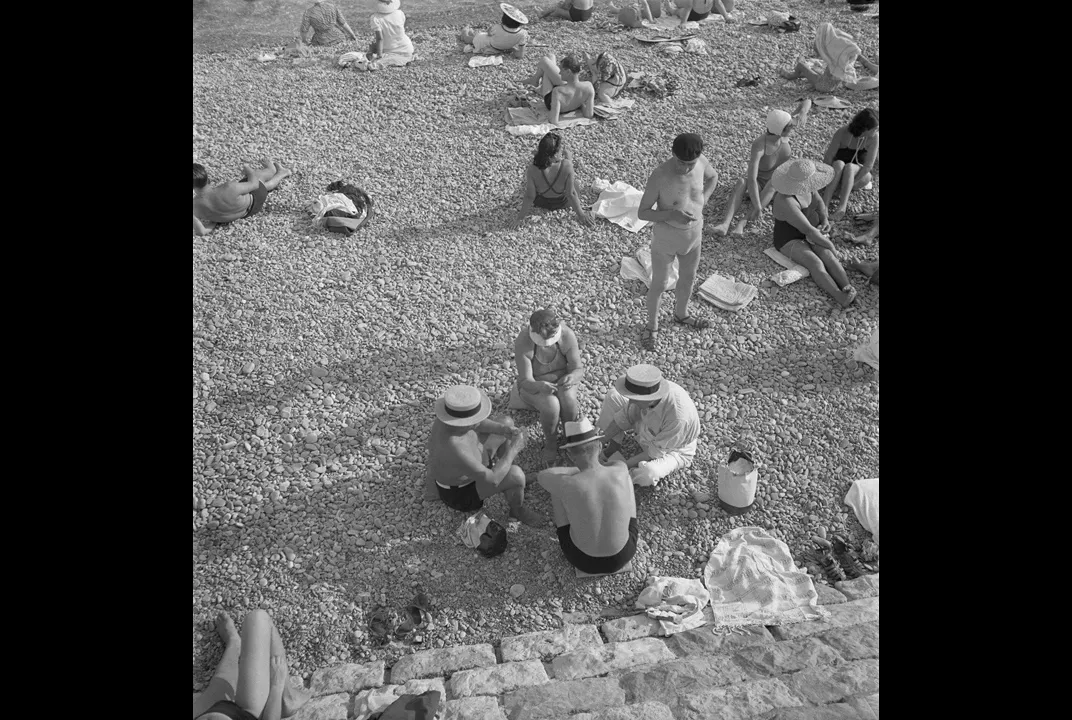

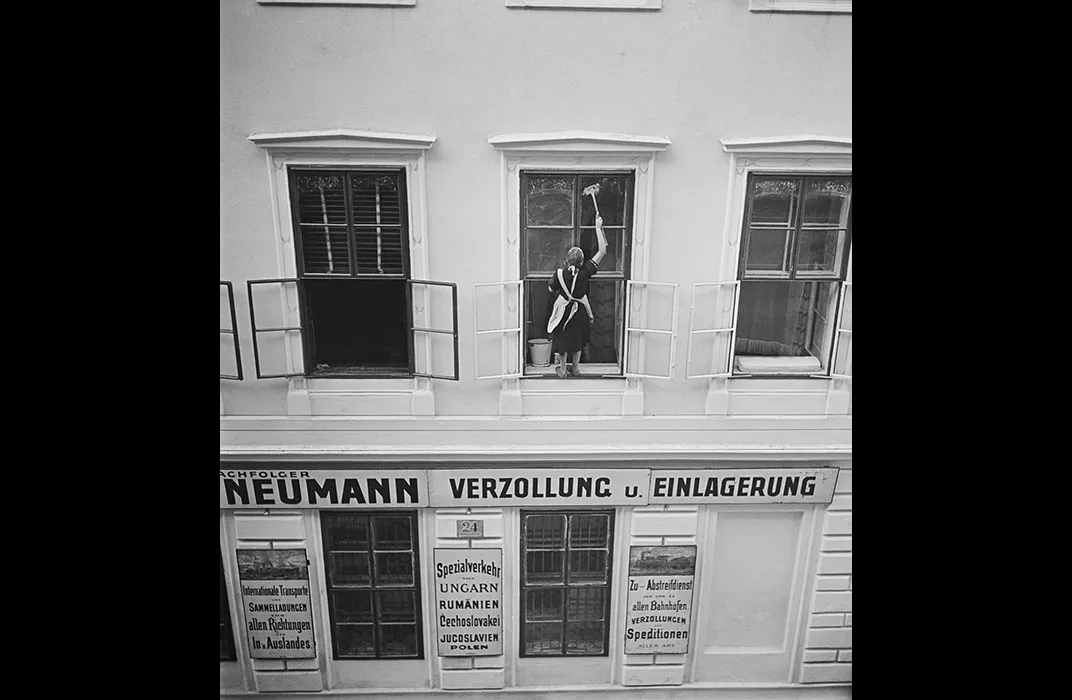

Vishniac’s negatives, in fact, paint a very different picture than the one we might imagine of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe before the war. Instead of the solemn images of black-hatted men and schoolboys with curls (payos) , they depict theatrical performers, women tending shops, and other everyday scenes—all distinctly relatable. “It shows a very different aspect of Jewish life,” says Benton. “It shows the richness and diversity of that world.”

Digitizing the archive also makes it available to researchers around the world for study. Given the breadth of archive, these could range from historians studying the rise of Nazi power in Berlin to photography experts looking at the documentary movement and comparing Vishniac to more acclaimed photographers such as Dorothea Lange.

But in the archives, interspersed with these chronicles of Jewish communities, are photographs of hormones and skin cells. In the 1960s, Vishniac, also a trained biologist, pioneered techniques in photomicroscopy.

The ICP team is working to digitize Vishniac’s printed images, films, and correspondence to flesh out the archive. As more archival material is scanned, historians at USHMM will follow more leads and hopefully fill in some blanks. Because, as Benton notes, “as the survivors die out, the weight will fall on photos to tell their stories.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/f3/e0f31142-2d88-43fa-b9f4-569587055cf5/vishniac_dancers_emily_frankel_and_mark_ryderedit.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)