Should LBJ Be Ranked Alongside Lincoln?

Robert Caro, the esteemed biographer of Lyndon Baines Johnson, talks on the Shakespearean life of the 36th president

It has become one of the great suspense stories in American letters, the nonfiction equivalent of Ahab and the white whale: Robert Caro and his leviathan, Lyndon Baines Johnson. Caro, perhaps the pre-eminent historian of 20th-century America, and Johnson, one of the most transformative 20th-century presidents—in ways triumphant and tragic—and one of the great divided souls in American history or literature.

When Caro set out to write his history, The Years of Lyndon Johnson, he thought it would take two volumes. His new Volume 4, The Passage of Power, traces LBJ from his heights as Senate leader and devotes most of its nearly 600 pages to the first seven weeks of LBJ’s presidency, concluding with his deeply stirring speeches on civil rights and the war on poverty.

Which means his grand narrative—now some 3,200 pages—still hasn’t reached Vietnam. Like a five-act tragedy without the fifth act. Here’s where the suspense comes in: Will he get there?

In 2009 Caro told C-Span’s Brian Lamb that he had completed the stateside research on Vietnam but before writing about it, “I want to go there and really get more of a feel for it on the ground.” Meaning, to actually live there for a while, as he’d lived in LBJ’s hardscrabble Texas Hill Country while writing the first volume, The Path to Power.

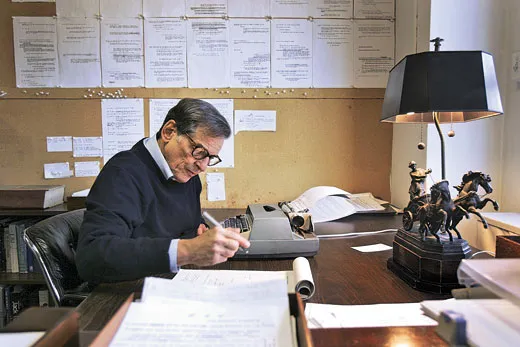

Caro still plans to live in Vietnam, he told me when I visited him in his Manhattan office recently. He’s 76 now. There has been an average of ten years between the last three volumes’ appearances. You do the math.

I’m pulling for him to complete the now 30-year marathon, and the guy who met me at his Manhattan office looked fit enough for the ordeal of his work, more like a harried assistant prof at Princeton, where he studied. He was in the midst of frantically finishing off his galleys and chapter notes and told me he just realized he hadn’t eaten all day (it was 4 p.m.), offered me a banana—the only food in the office—and when I declined, I was relieved to see, ate it himself. The man is driven.

Those who have thought of Caro as one of LBJ’s harshest critics will be surprised at the often unmediated awe he expresses in this new book: “In the lifetime of Lyndon Johnson,” he writes of LBJ’s first weeks as president, “this period stands out as different from the rest, as one of that life’s finest moments, as a moment not only masterful, but in its way, heroic.”

But how to reconcile this heroism with the deadly lurch into Vietnam? I have my suspicions as to what he’s going to do, and you might too when you get to the final page of this book where he writes, after paying tribute to this heroic period, about the return to the dark side, “If he had held in check those forces [of his dark side] within him, had conquered himself, for a while, he wasn’t going to be able to do it for long.”

“Do you mean,” I asked him, “that the very mastery of power which he’d used for civil rights gave him the hubris to feel he could conquer anything, even Vietnam?”

“I’ll have to take a pass on that,” Caro said. He won’t reveal anything until he writes it.

“But do you have the last sentence written?” I asked. He’s said in the past he always writes the last sentence of a book before starting it. This would be the last sentence of the entire work, now projected to be five volumes.

To that he answers “yes.” He won’t, of course, say what it is.

Will that last sentence reveal a coherence in the portrait that he will have painted of LBJ’s profoundly divided soul, a division that makes him such a great and mystifying character? Worthy of Melville. Or Conrad. Or will the white whale slip away into the heart of darkness that is Vietnam?

The new volume takes us back to where his last Pulitzer winner, the 1,200-page-long Master of the Senate, leaves off, with LBJ having, by sheer force of will and legislative legerdemain, coerced the obstructionist, racist-dominated Senate to pass the first civil rights bill since Reconstruction. It follows him through his strangely reticent, self-defeating attempt to win the Democratic nomination in 1960 (a window into an injured part of his psyche, Caro believes), portrays his sudden radical diminishment as vice president and sets up, as a dominant theme of the book, the bitter blood feud between LBJ and Robert F. Kennedy.

This mortal struggle explodes into view over RFK’s attempt to deny Johnson the vice presidential nomination. Caro captures the pathos of LBJ’s sudden loss of power as VP, “neutered” and baited by the Kennedy echelon, powerless after so long wielding power. And the sudden reversal of fortune that makes him once again master on November 22, 1963—and suddenly makes Bobby Kennedy the embittered outsider.

As I took the elevator up to Caro’s nondescript office on 57th Street, I found myself thinking that he was doing something different in this book than he had in the previous ones. The first three were focused on power, how “power reveals” as he puts it, something he began investigating in his first book in 1974, The Power Broker, about New York City’s master builder Robert Moses.

But this fourth LBJ volume seems to me to focus on the mysteries of character as much as it does on the mysteries of power. Specifically in the larger-than-life characters of LBJ and RFK and how each of them was such a profoundly divided character combining vicious cruelty and stirring kindness, alternately, almost simultaneously. And how each of them represented to the other an externalized embodiment of his own inner demons.

When I tried this theory out on Caro he said, “You’re making me feel very good. I’ll tell Ina [his wife and research partner] tonight. This is what I felt when I was writing the book. It’s about character.”

I don’t know if I was getting a bit of the ol’ LBJ treatment here, but he proceeded to describe how he learned about the momentous first meeting of these two titans, in 1953. “That first scene....Horace Busby [an LBJ aide] told me about the first meeting and I thought ‘that’s the greatest story! But I’ll never use it, I only have one source.’ And I called him and I said ‘Was anyone else there?’ and he said ‘Oh yeah George Reedy [LBJ’s press secretary] was there’ and I called Reedy [and he confirmed it].”

Caro’s account captures the scrupulousness of his reporting: He wouldn’t have used this primal scene if he hadn’t gotten a second source. Caro’s work is a monument to the value and primacy of unmediated fact in a culture ceaselessly debating truth and truthiness in nonfiction. Fact doesn’t necessarily equal truth, but truth must begin with fact.

“When they meet in the [Senate] cafeteria,” Caro tells me, “Bobby Kennedy is sitting at Joe McCarthy’s table and Johnson comes up to him. And Reedy says this thing to me: ‘You ever see two dogs come into a room and they’ve never seen each other but the hair rises on the back of their neck?’ Those two people hated each other from the first moment they saw each other.”

It’s very Shakespearean, this blood feud. The Hamlet analogy is apt, Caro told me. “The dead king has a brother and the brother has, in Shakespearean terms, a ‘faction’ and the faction is loyal to the brother and will follow him everywhere and the brother hates the king. It’s...the whole relationship.”

When it comes to Shakespeare, though, the character Caro thinks most resembles LBJ’s dividedness and manipulative political skills is Mark Antony in Julius Caesar.

“Is there an actor you think played Mark Antony well?” Caro asks me.

“Brando?” I ventured. It’s an opinion I’d argued in a book called The Shakespeare Wars, referring to his performance in the underrated 1953 film of Julius Caesar.

“I’ve never seen anyone else do him just right,” Caro agreed. “No one can figure out what he’s like, he loves Brutus, but you can see the calculation.”

It occurred to me only after I left to connect LBJ with another great Brando role, as the Vietnam-crazed Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. Will LBJ become Caro’s Kurtz?

One of the great mysteries of character that haunts Caro’s LBJ volumes is the question of Johnson’s true attitude, or two attitudes, on race. I know that I am not alone in wondering whether Johnson’s “conversion” from loyal tool of racist obstructionists in the Senate to civil rights bill advocate was opportunistic calculation—the need to become a “national” figure, not a Southern caricature, if he wanted to become president. Or whether his heart was in the right place and it was the obstructionism in his early Senate years that was the opportunistic facade.

But it’s clear in this book that Caro has come to believe that LBJ deserves a place alongside Lincoln (who also had his own racial “issues”) as a champion of equal rights and racial comity.

Caro traces LBJ’s instinct, his conviction, on the point back to a story he dug up from 1927 when LBJ was teaching in a school for Mexican kids. “Johnson’s out of college,” Caro told me, “He’s the most ruthless guy that you can imagine. Yet in the middle of it he goes down to teach in this Mexican-American town, in Cotulla. So I interviewed some of the kids who were there and I wrote the line [that] summed up my feelings: ‘No teacher had ever cared if these kids learned or not. This teacher cared.’ But then you could say that wasn’t really about race. That was about Lyndon Johnson trying to do the best job he could in whatever job he had....

“But the thing that got me was I found this interview with the janitor at the school. His name was Thomas Coranado. He said Johnson felt all these kids had to learn English. And he also felt the janitor had to learn English. So he bought him a textbook. And he would sit on the steps of the school with the janitor before and after school every day and, the exact quote is in my book but it was something like, ‘Mr. Johnson would pronounce words; I would repeat. Mr. Johnson would spell; I would repeat.’ And I said ‘That’s a man who genuinely wanted to help poor people and people of color all of his life.’”

Caro pauses. It’s a sweeping statement, which he knows presents a problem.

“That was 1927....So you say, now—until 1957, which is 30 years [later]—there’s not a trace of this. He’s not only a Southern vote, he helps [senator] Richard Russell defeat all these civil rights bills; he’s an active participant. So, all of a sudden in 1957 [he forces through that first civil rights bill since Reconstruction] because why?

“Because the strongest force in Lyndon Johnson’s life is ambition. It’s always ambition, it’s not compassion. But all of a sudden in ’57, he realizes he’s tried for the presidency in ’56, he can’t get it because he’s from the South. He realizes he has to pass a civil rights bill. So for the first time in his life, ambition and compassion coincide. To watch Lyndon Johnson, as Senate majority leader, pass that civil rights bill....You say, this is impossible, no one can do this.

“To watch him get it through one piece at a time is to watch political genius, legislative genius, in action. And you say, OK, it’s a lousy bill but it’s the first bill, you had to get the first one. Now it’s ’64. He says this thing to [special assistant] Richard Goodwin, ‘That was a lousy bill. But now I have the power.’ He says, ‘I swore all my life that if I could help those kids from Cotulla, I was going to do it. Now I have the power and I mean to use it.’ And you say, I believe that.

“So we passed [the Voting Rights Act] of 1965. So in 2008, Obama becomes president. So that’s 43 years; that’s a blink of history’s eye. Lyndon Johnson passes the act and changes America. Yeah, I do think he deserves comparison with Lincoln.”

“That’s what’s so interesting,” I say, “Because...yeah, it came across as deeply felt and yet it’s side by side with qualities that you call deeply deceptive and all these other bad things. I think you use the term at one point, [his character weaves together] ‘gold and black braids.’”

“Bright and dark threads in character,” he replies.

I ask him about one of the darkest threads: Bobby Baker. LBJ’s “protégé,” a bagman, fixer, pimp. People have forgotten just how much of an open secret the sexual goings-on were in Baker’s Quorum Club, the Capitol Hill hideaway he stocked with liquor and girls. It would be an earthshaking scandal in today’s climate and probably about a third of Congress would have to resign in disgrace if it happened now.

Caro’s narrative has an astonishing reminder of how close the investigation of Bobby Baker came to bringing LBJ down. In fact, until now, Caro believes, no one has put together just what a close call it was.

He gets up from his chair and goes to a file cabinet and pulls out a Life magazine with a cover story—MISCONDUCT IN HIGH PLACES-THE BOBBY BAKER BOMBSHELL—which came out on November 18, 1963. Life had an investigative SWAT team on the case! The Senate had a subcommittee taking testimony about kickbacks and extortion Baker engaged in on LBJ’s behalf while he was vice president. The kind of thing that got Spiro Agnew kicked out of the vice presidency.

It was in reading this testimony that Caro made a remarkable discovery. He goes to another desk and digs out a timeworn Senate investigative hearing transcript from December 1964 and points to a page on which a witness named Reynolds tells the Senate investigators he had previously testified on this matter on November 22, 1963, the day JFK was assassinated.

“A thousand books on the assassination,” Caro says, “And I don’t know one that realizes that at that very moment Lyndon Johnson’s world was to come crashing down, Reynolds is giving them these documents.”

Caro still gets excited talking about his discovery.

“Oh, it’s a great....Nobody writes this!” he says. “Bobby Baker says the thing I quote in the book. ‘If I had talked it would have inflicted a mortal wound on LBJ.’” And it starts coming out—and stops coming out—just as JFK receives his mortal wound in Dallas. The thrilling way Caro intercuts the dramatic testimony with the motorcade’s progress to its fatal destiny is a tour de force of narrative.

“Can I show you something?” Caro goes over to another desk and starts searching for a document. He finds it. “These are the invoices Reynolds produced,” he tells me. “‘To Senator Lyndon Johnson,’ you know?”

The transcript has photographs of canceled kickback checks.

“Look at that! Right in print,” I say. “Checks, canceled checks.”

“To the Lyndon Johnson Company,” he reads to me, “To LBJ Company.”

“This is the life insurance kickback scam?”

“Yes. Yeah, KTBC [ Johnson’s TV station, which he extorted advertising for from lobbyists]. But this is the line that got me. The counsel to the Rules Committee says, ‘So you started testifying what time?’ And [Reynolds] says, ‘Ten o’clock.’ That’s on November 22. He was testifying while President Kennedy was being shot!”

It’s thrilling to see how excited Caro, who may be one of the great investigative reporters of our time, can still get from discoveries like this.

So what do we make of it all, this down and dirty corruption alongside the soaring “we shall overcome” achievements?

“The most significant phrase in the whole book,” Caro tells me, is when LBJ tells Congress, “‘We’ve been talking about this for a hundred years. Now it’s time to write it into the books of law.’”

“There’s something biblical about that, isn’t there?” I asked.

“Or Shakespearean.” he says.

In the light of LBJ’s echoing Martin Luther King’s “we shall overcome,” I asked whether Caro felt, as King put it, that “the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice”?

“Johnson’s life makes you think about that question,” Caro says. “Just like Martin Luther King’s life. And I think a part of it to me is that Obama is president.

“In 1957, blacks can’t really vote in the South in significant numbers. When LBJ leaves the presidency, blacks are empowered, and as a result, we have an African-American president, so what way does the arc bend? It’s bending, all right.”

I didn’t want to spoil the moment but I felt I had to add: “Except for the two million or so Vietnamese peasants who [died]...”

“You can’t even get a number [for the dead in Vietnam],” he says. “For the next book I’m going to find—”

“The number?”

“You look at these picture spreads in Life and Look of LBJ visiting the amputees in the hospital and you say, you’re also writing about the guy who did this.”

Caro is really taking on the most difficult question in history, trying to find a moral direction in the actions of such morally divided men and nations. If anyone can do it, he can.

Before I left, before he had to go back to his galleys and chapter notes, I wanted to find out the answer to a question about Caro’s own history. When I asked him what had set him on his own arc, he told me an amazing story about his first newspaper job in 1957, which was not at Newsday, as I thought, but a little rag called the New Brunswick [New Jersey] Daily Home News. It’s a remarkable tale of his own firsthand experience of political corruption and racism that explains a lot about his future fascination with power.

“This was such a lousy newspaper that the chief political writer—an old guy; he actually covered the Lindbergh kidnapping—would take a leave of absence every election—the chief political writer!—to write speeches for the Middlesex County Democratic organization.”

“I see,” I said.

“So he gets a minor heart attack but he has to take time off, and it’s right before...the election. So he can’t do this job which pays many times the salary. And he has to have a substitute who’s no threat to him. So who better than this young schmuck?

“So I found myself working for the Middlesex County Democratic boss. At New Brunswick there was a guy named Joe. Tough old guy. And I was this guy from Princeton. But he took a real shine to me.

“Oh God,” Caro interrupts himself, “I hadn’t thought of this [for a long time]. So I write the speeches for the mayor and four council members, and he says, ‘Those were good speeches.’ He pulls out this roll of fifty-dollar bills. And he peels off—I was making, my salary was $52.50 a week, and he peels off all these fifty-dollar bills and he gives them to me! And I didn’t know...all this money.

“I loved him. I thought he’s teaching me. On Election Day, however, he rode the polls with a police captain, a real son-of-a-bitch, and I knew he was a son-of-a-bitch because I covered the Justice of the Peace Court, and you used to be able to hear the cells...and you could hear them beating up people. And at every poll, out would come a policeman and tell him how things were going, you know. And they were having trouble with the black voters. I don’t remember if they had a black candidate or what. So...the captain would say something and they’d arrest people. And I couldn’t stand it.

“We got to this one polling place and there was a large group of black people. And this police sergeant or whatever came over and talked to them about how these people were really giving him trouble, which I guess meant having an honest vote instead of letting...I didn’t know. And the policeman on duty escorted these people into the back of this paddy wagon.

“This was ’57, it was like they expected it. And I got out of the car. And this was a moment that changed [my life].

“I just got out and left. I knew I wanted to be out with them, with the people there, instead of in the car.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)