Shutting Down Hawai‘i: A Historical Perspective on Epidemics in the Islands

A museum director looks to the past to explain why ‘Aloha’ is as necessary as ever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/72/c37278e7-8040-45e1-89e8-7e9bd028ac8f/hawaii-lead.png)

According to the Hawai‘i Department of Health, as of March 24, the state has seen 90 cases of infection from coronavirus since the beginning of the outbreak. Here on the island of Kaua‘i, where I reside, only four have been reported to date—two are visitors who got sick on Maui and decided to travel on to Kaua‘i anyway, one is a resident returning from travel, and the fourth is another visitor. At this time we are hopeful that there is no community contagion.

Unsurprisingly, many local people here—and Native Hawaiians in particular—have been publicly (and not always gently) encouraging visitors to go home and stay away—a trend seen on other islands and remote places. Tensions have run hot as visitors demand “Where is the aloha?” and residents insist that visitors show their aloha by leaving.

Because one thing Hawaiians know about is epidemics. Foreign diseases have come through here before, and they have inflicted unfathomable damage. Hence many locals have been pushing the mayors and Governor David Ige to shut down the islands completely to outside travel. (On Saturday, Ige ordered that all incoming travelers be quarantined for 14 days and an emergency, statewide stay-at-home order was effective as of this morning.) This is not an easy call, as the visitor industry is a major portion of the economy.

To understand the eagerness behind Hawai‘i residents to shut down the islands to travel, the current epidemic must be understood in geographic and historical context. The Hawaiian islands have been referred to as “the last landfall”: about 2,500 miles from the nearest other island, and further than that from the nearest continent, the islands evolved in relative isolation. Plants and birds that got here adapted to suit the local environment, creating a place where 97 percent of all native plant species and most of the native birds are found nowhere else on earth. The Hawaiian people, arriving here more than a thousand years ago after millennia of migration out of Southeast Asia, were similarly cut off from the rest of their species, and—like the native peoples of the Americas—never experienced the diseases that had affected the Old World. This made them “virgin populations” who had not, through exposure, developed resilience or immunities.

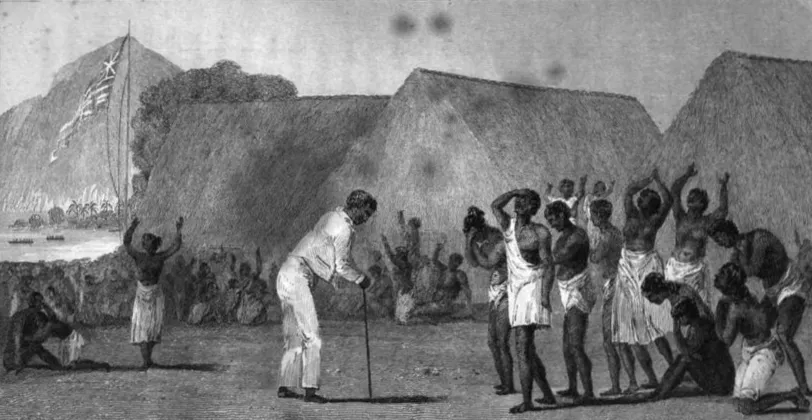

Thus the introduction of the first outside diseases in 1778, with the arrival of Captain Cook, was catastrophic. Cook visited the island of Ni‘ihau, on the far northwestern end of the chain, in January 17 of that year. His journals remark on the health of the people, and the absence of disease. He knew his men were carrying venereal diseases, and he tried to keep them away from the native women. But when their ships were blown offshore, men that were left on the island had to stay for three days. Nine months later when Cook returned to the islands, he found that the venereal disease had spread throughout the entire archipelago. While it’s uncertain exactly which disease it was, the impact was unmistakable. By the time French explorer La Pérouse arrived in the 1790s, he said of Hawaiian women that “their dress permitted us to observe, in most of them, traces of the ravages occasioned by the venereal disease.” The disease did not necessarily kill outright, but it could render the people infertile, beginning the steep downward decline of the Hawaiian population.

Then, as the nascent Hawaiian Kingdom worked to forge itself into an independent nation, foreign ships brought epidemics in waves: cholera (1804), influenza (1820s), mumps (1839), measles and whooping cough (1848-9) and smallpox (1853). These led King Kamehameha V, in 1869, to establish a quarantine station on a small island off Honolulu. Leprosy arrived around that time and led the kingdom, under pressure from Western advisors, to quarantine those suspected of being infected (predominantly Native Hawaiians) on the island of Moloka‘i—a move that has since been interpreted as another means by which Native Hawaiians were intentionally disempowered.

Of the earlier epidemics, what we know comes predominantly through the writings of Western observers of the times, particularly the American Congregationalist missionaries who had begun arriving in 1820. Levi Chamberlain from Dover, Vermont, wrote in 1829 that:

There have been two seasons of destructive sickness, both within the period of thirty years, by which, according to the account of the natives, more than one half of the population of the island was swept away. The united testimony of all of whom I have ever made any inquiry respecting the sickness, has been that, ‘Greater was the number of the dead, than of the living.’

Seven years later, the Missionary Herald stated that “From the bills of mortality...it appears probable that there have been not less than 100,000 deaths in the Sandwich [Hawaiian] Islands, of every period of life from infancy to old age, since the arrival of the mission fifteen years ago.” And after the 1853 smallpox epidemic, it was reported in one location that “Out of a population of about two thousand eight hundred, more than twelve hundred are known to have died; and it is not to be supposed that all the cases of mortality were reported.”

Lacking the theories of contagion and immunology common today, the missionaries had other ways to account for the rapid dying off of the Hawaiian people. Their first letter back to the missionary headquarters in Massachusetts remarked that “God has hitherto preserved our health; but the heathen around us are wasting away by disease, induced not by the climate, but by their imprudence and vices” (MH 4/21:112). After an epidemic in 1850, a missionary named Titus Coan reported that “No opportunity was omitted, and no efforts were spared, to impress upon the people the idea that the Lord was holding the rod over them, and to stimulate and encourage them to profit by the chastisement, by humiliation, confession and penitence, by loving, adoring and fearing their heavenly Father, and by saying unto him with Job, ‘Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him’”

But when illness did attack the mission, the appraisal was entirely different, asserting that their Christian God was testing them with affliction: “These afflictions we received from the kind hand of our covenant God and Father. ‘Whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth; and scourgeth every son, whom he receiveth.’ May our afflictions be sanctified, and then they will be counted among our choicest blessings.” Or the non-causative remark, “The climate of the Sandwich Islands is believed to be one of the most salubrious in the tropical regions. But sickness and death are found in every clime” The Hawaiians died due to their vices, while the missionaries got ill randomly, or were called up by God for His purposes.

The missionaries built a massive discourse of native vices to explain the sad but “inevitable” dying off of the Hawaiian people. The introduction of diseases by foreigner was only a contributing factor to an inherent, spiritual and physical deficiency in the Hawaiian peoples:

The lower classes are a mass of corruption. Words cannot express the depths of vice and degradation to which they have been sunk from time immemorial. Their very blood is corrupted and the springs of life tainted with disease, by which a premature old age and untimely death ensues. Their intercourse with foreigners has greatly aggravated with pitiable condition.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions’ Annual Report for 1835 asserted, “It is well known that the population of the islands was diminishing when the mission was first established. This was owing to the vices of the people” An 1848 survey of the missionaries conducted by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Minister of Foreign Relations R.C. Wyllie, on a number of topics including causes of the decrease in population, elicited the following responses: licentiousness, bad mothering, impotence due to excessive sex during youth, native houses, native doctors, lack of land tenure, inappropriate use of clothing, idolatry, indolence and lack of value on life. These ideas permeate 19th century discourses on the Hawaiians. In a lecture titled “Why are the Hawaiians Dying Out?” delivered before the Honolulu Social Science Association in 1888, Reverend S.E. Bishop summarized a similar list of causes in the following numerical order:

- Unchastity

- Drunkenness

- Oppression by the Chiefs

- Infectious and Epidemic Diseases

- Kahunas and Sorcery

- Idolatry

- Wifeless Chinese

This today is a lesson on how easy it is to assign blame in the absence of knowledge and understanding. Scientific understanding of germs and contagion did not evolve until the mid 1800s, and did not receive firm validation until Louis Pasteur’s work the 1860s. In the absence of this science, missionary letters show how easy it can be to mobilize the effects of an epidemic for selfish causes. In the Hawaiian Islands it was the non-Native community of Westerners, on whom these diseases had relatively little effect, who wanted access to land. The ABCFM annual report of 1859 stated,

The native population is decreasing. Whether this decrease will be stayed before the race become extinct, is doubtful. Foreign settlers are coming in, more and more....Much of the property is passing into the hands of the foreign community. The Islands present many attractions to foreign residents, and they are to be inhabited in all time to come, we hope and believe, by a Christian people. The labors of the missionaries, and the settlement of their children there, will make the people of the Islands, of whatever race, to resemble, in some measure, what the Pilgrim Fathers made the people of New England [emphasis added].

Contemporary scholarship estimates that here, as in the Americas, introduced diseases reduced the Native population by as much as 90 percent over 50 years. Though the Hawaiian population ultimately bounced back, starting around 1900, the damage had been done: people of Western descent had overthrown the legitimate government of the kingdom, the United States had annexed the islands against the wishes of the Hawaiian people, and Americanization had set it, culminating with statehood in 1959. Cheap airfares in the 1960s brought new waves of immigrants, displacing local people and raising the price of land. Today, only 21 percent of the state’s population claim Native Hawaiian descent. And the high cost of living (the median price for a single family home is $795K) combined with disproportionately low wages has forced many Native Hawaiians to move away.

The islands receive approximately 10 million visitors yearly, to a population of 1.4 million. Kaua‘i, an island of 73,000 residents, receives between 100,000-140,000 visitors per month. And not all of these people leave. Those who can afford to, including the occasional billionaire, add to the rising cost of land and housing.

Native Hawaiians have had more than enough of this, and have been protesting the impact of outsiders as long as there is written record. Before the coronavirus crisis, the most recent high-profile example was the proposed telescope atop Mauna Kea on the island of Hawai‘i, which became a line in the sand for Hawaiians opposed to having their land taken and their sacred sites desecrated.

But the rise and spread of the virus and the threat it presented to the more remote population of Kaua‘i notched the protests up significantly. So far the cases on the island, where my museum, the Grove Farm Plantation Homestead, is based, seem mostly to be contained. But as Lee Evslin, retired physician and the CEO of the island’s main hospital said, “With our remote landmass and numbers of visitors, we are one of the most vulnerable states of all.”

The Grand Princess cruise ship, whose passengers were all quarantined after docking in the Port of Oakland, stopped on Kaua‘i a few days before some tested positive for the disease. A number of people came off the ship here and a dozen or so toured the museum. That was a close call, and led to demands that the cruise ships all be banned from coming to Kaua‘i (they since stopped coming here).

As visitors rail in online communities about the lack of aloha they are experiencing (some going so far as to say they felt they were being treated like lepers), the real question is whether or not each person respects the unique culture and history of Hawai‘i and the fragility of this place and its people. The Hawaiian Kingdom was never about race or skin color. Now that all Americans are in that position of being a “virgin population,” it’s time for the non-Hawaiian residents and visitors to understand what the Native people here went through: how they died in droves, how they and their lifestyles were blamed for the illnesses brought in from outside, how this led to their kingdom being taken from them and their lands being overrun by foreigners whose individualism is antithetical to life on small islands. The Hawaiian experience is the very definition of intergenerational trauma. They should not be asked to give aloha. They should receive it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)