The Strange Case of George Washington’s Disappearing Sash

How an early (and controversial) symbol of the American republic was lost to the annals of history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/f8/58f8a943-33ef-48ad-aef2-31804abc490d/2-george_washington_by_charles_willson_peale_1776-2-wr.jpg)

One winter day in December 1775, months after the battles at Concord and Lexington marked the beginning of the Revolutionary War, the nascent American military formally met its commander-in-chief. A group of Virginia rifleman found themselves in the middle of a massive snowball fight with a regiment of quick-talking New Englanders who ridiculed the strangely dressed Virginians in their “white linen frocks, ruffled and fringed.” The colonies were still strangers to each other at this point: The Declaration of Independence was months away, and the ragtag army representing the rebels was far from formally “American.” The meeting of nearly 1,000 soldiers quickly devolved into an all-out brawl on the snowy grounds of Harvard Yard.

But as quickly as it had begun, the fighting screeched to a halt. A man charged into the middle of the fray on horseback, seizing two men into the air with his bare hands and ordering the militiamen to stand down. Few of the assembled soldiers recognized him as George Washington: Most Americans barely knew what the untested general looked like, let alone anything about his mettle. But part of his uniform announced his identity: his sash. The blue-green shimmering ribbon of silk caught the afternoon light, a formal sign of his command and, according to historians, one of the earliest symbols of national identity in a nascent country that lacked a constitution and a flag. The snowball fight ceased immediately — the general was on the prowl.

George Washington’s sash remains one of the Revolutionary War’s most extraordinary artifacts. Like the unknown Virginian leading the rebellion against the British, the powder-blue ribbon became one of the earliest symbols of the United States. But for some reason, the sash has languished in relative obscurity, resigned to back rooms and dusty archives for decades— until now.

On a warm day in September, I met Philip Mead, a historian and curator at the Museum of the American Revolution, at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After years in historical limbo, the sash turned up in the Peabody’s archives, and Mead can’t wait to revisit the relic after years of researching it. Washington, who bought the sash for three shillings and four pence in July 1775, used it as part of his color-coded system to distinguish officers from one another; according to Mead’s research, Washington himself documented his purchase of “a Ribband to distinguish myself” in his journal. His choice of blue was meant to evoke the traditional colors of the Whig party in England—the ideological model for the revolutionaries gearing up for insurrection across the Atlantic.

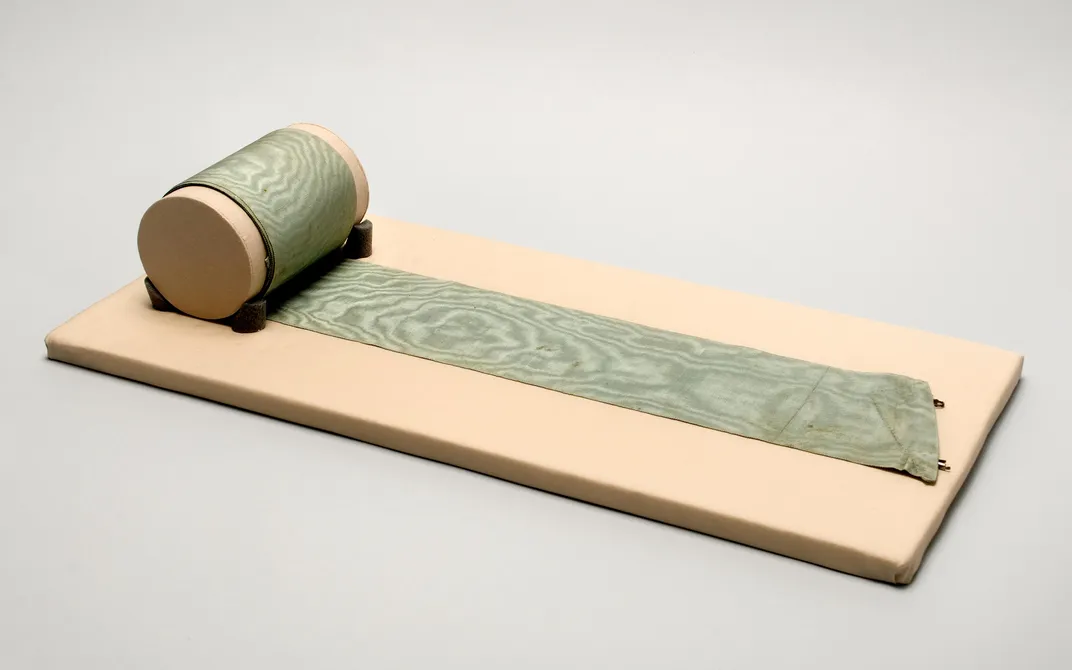

The sash itself is in incredible condition. Exposure to light and oxygen has gradually muted the ribbed silk ribbon’s vibrant blue, but the unique folds in the fabric match the ribbon worn by Washington in some of the contemporary paintings of the general. Despite the erosion of history, the sash still retains brownish stains of sweat, marks of Washington’s perseverance on the battlefield. It is one of the future President’s rarest and most personal relics.

But until Mead stumbled upon the ribbon in 2011, the object had all but vanished. How did such an important object go missing for centuries? Historical accounts of Washington’s uniform make little mention of a ceremonial ribbon. Did someone, perhaps even Washington himself, try to hide its historical legacy?

Not quite. Historians suggest that Washington may have indeed stopped wearing the moiré silk ribbon shortly after he purchased it, uncomfortable with the sash’s resemblance to decorations of British and French officers. The sash looked too much like a symbol of hierarchy and aristocracy for a general intent on bringing democracy to the Continental Army. Even though the ribbon served a formal military function—asserting Washington’s authority to his troops and giving him diplomatic standing with other countries—it was deemed too haughty for the would-be democracy even by his French allies. “[His uniform] is exactly like that of his soldiers,” observed the Marquis de Barbé-Marbois, a French officer assisting the Continental Army, in a 1779 letter shortly after Washington stopped wearing the sash. “Formerly, on solemn occasions…he wore a large blue ribbon, but he has given up that unrepublican distinction."

“Washington himself was, along with every other colonist, in the process of discovering what this new country was going to mean,” says Mead. “This kind of decoration would have been pretentious for all but the highest-ranking aristocracy. He was attaching himself to a standard of aristocracy that’s totally antithetical to the Revolution.”

It’s unclear, Mead says, how widely this opinion spread among the colonies, but the French connection seems to have made Washington increasingly uneasy—especially given rumors after the war that he had received the rank of marshal in the French military. Washington eventually abandoned it even under ceremonial circumstances, switching to a pair of epaulettes instead.

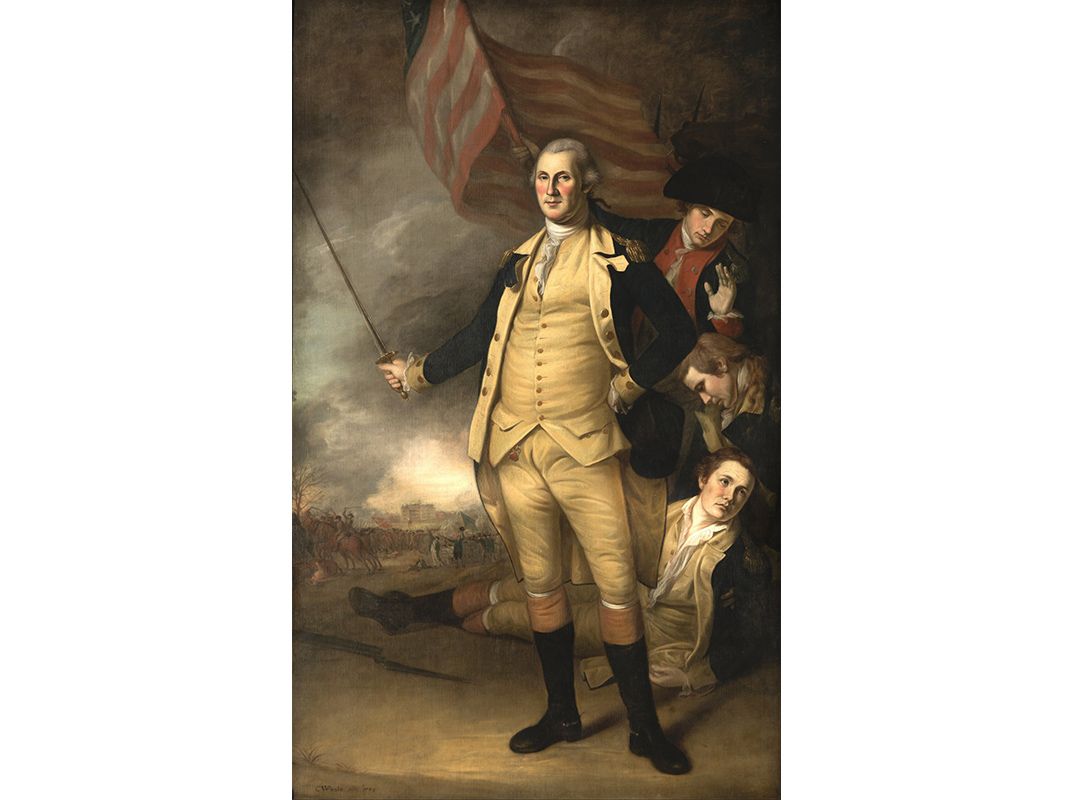

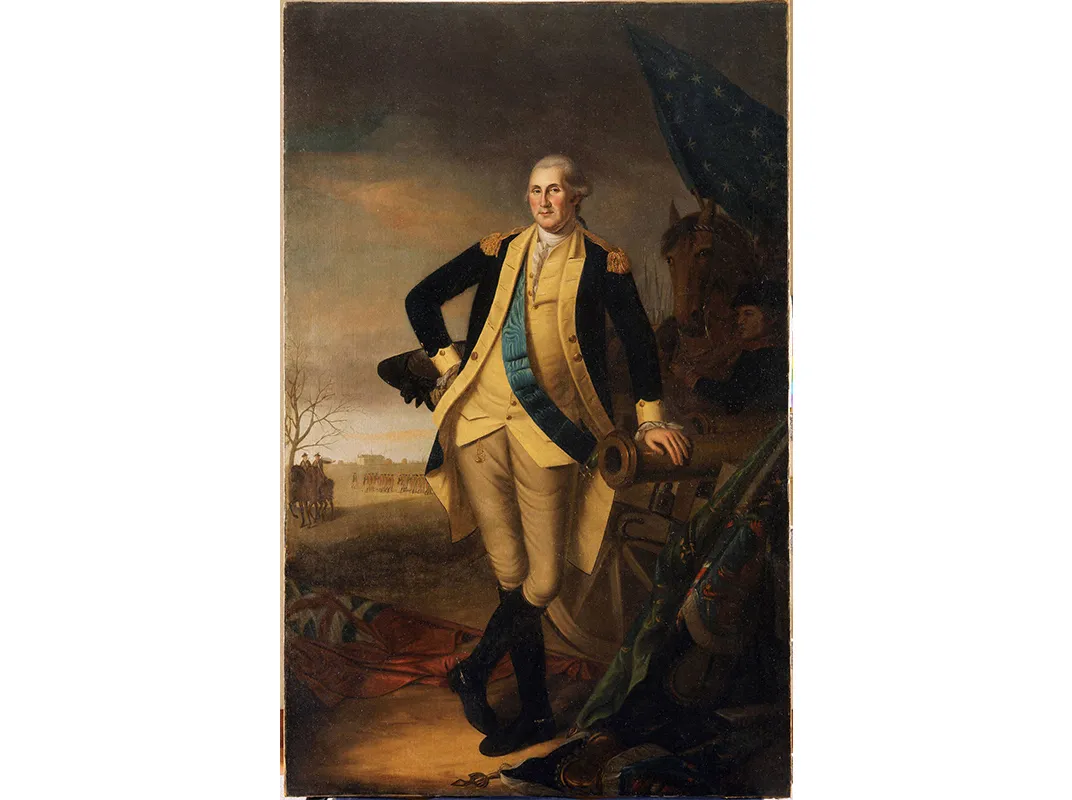

But though Washington abandoned the sash because of the ideological clash it represented, the sash itself seems to have disappeared from sight by accident rather than design. Washington gave the sash to Charles Willson Peale, the legendary artist known for his majestic portrait of leading figures of the Revolutionary War. Peale painted the general wearing the sash multiple times, including in an iconic 1776 portrait commissioned by John Hancock. But Peale never displayed it in his namesake Philadelphia museum, and it disappeared from subsequent historical paintings of the general, including Peale’s 1784 portrait.

According to Peale scholar and descendant Charles Coleman Sellers, the painter “never thought of placing it in a natural history museum.” A British tourist who visited a Peale Museum branch in Baltimore some time later found the ribbon mixed in a display of other Revolutionary War artifacts, distinguished by a simple label: “Washington’s Sash. Presented by Himself.”

The artifact’s provenance becomes even more muddled after that. After the Peale collection was dissolved in 1849, the sash and many other artifacts were sold in a sheriff’s auction to Boston Museum co-founders P.T. Barnum and Moses Kimball. After their museum burned down in 1893, it went on an odyssey from Kimball’s family to Harvard to a series of museum loans. At some point in the process, the sash’s original Peale label went missing. It became just another ribbon from the Revolutionary War.

The ribbon was “lost in plain sight,” as Mead puts it, falling between the cracks of the museum’s regular anthropological exhibits. He came across the sash almost totally by chance after running into his graduate advisor on the street in 2011. A renowned historian, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was at the time working an exhibit about Harvard’s collections called Tangible Things. The exhibit focused on “examining the assumptions of museum categorization,” and Ulrich had tasked her students with literally digging through Harvard’s collections for overlooked treasures, one of which was a sash that was missing any sort of identification. Had Mead ever heard of a piece of clothing like this — “tight, like a ribbon” — among Washington’s objects, Ulrich asked?

Mead’s jaw dropped: Was this Washington’s lost sash from the Peale paintings? He rushed to see the exhibit, and there it was—nestled between a Galapagos tortoise shell from Charles Darwin’s archive and rolled up on a little scroll.

Analysis of the ribbon by Mead and Harvard conservator T. Rose Holdcraft eventually confirmed its authenticity and ownership: it even had the same unique folds as the sash in the 1776 Peale. “It was an unlikely survivor to have been so overlooked,” said Mead.

After years of preservation and reconstruction efforts, the battered ribbon will finally go on display at Philadelphia’s new Museum of the American Revolution, set to open on April 19, 2017—a museum that will be a testament to the very events Washington’s sash witnessed.

“To think of this object as a witness object, not just of Washington but of so much of the Revolutionary War, is astounding,” says Mead. “This thing would’ve been on Washington at battles around New York, along the Delaware River, at Monmouth, at the ceremony celebrating the French alliance at Valley Forge, as the army fought its way into Trenton in the desperate days of December 1776. It is a witness to some of the most trying and well-known events of the Revolutionary War.”

With that furious snowball fight in 1775, Washington’s shimmering blue sash became a small but significant part of Revolutionary history. Now, after decades of obscurity, the general’s lost sash will finally get the preservation—and the recognition—it deserves.