The Suffragist Statue Trapped in a Broom Closet for 75 Years

The Portrait Monument was a testament to women’s struggle for the vote that remained hidden till 1997

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/1a/b21a5bdf-6c71-4b8a-b401-522a2e1ace95/portraitmonumentimage01.jpg)

Six months after the 19th amendment was ratified, giving women the vote in the United States, an assembly of more than 70 women’s organizations and members of Congress gathered at the Capitol Rotunda for the unveiling of a massive statue. The room in the U.S. Capitol sits beneath the high, domed ceiling and connects the House of Representatives and the Senate sides of the Capitol. The room holds everything from John Trumbull’s paintings of the American Revolution to statues of former presidents and important figures like Martin Luther King, Jr.

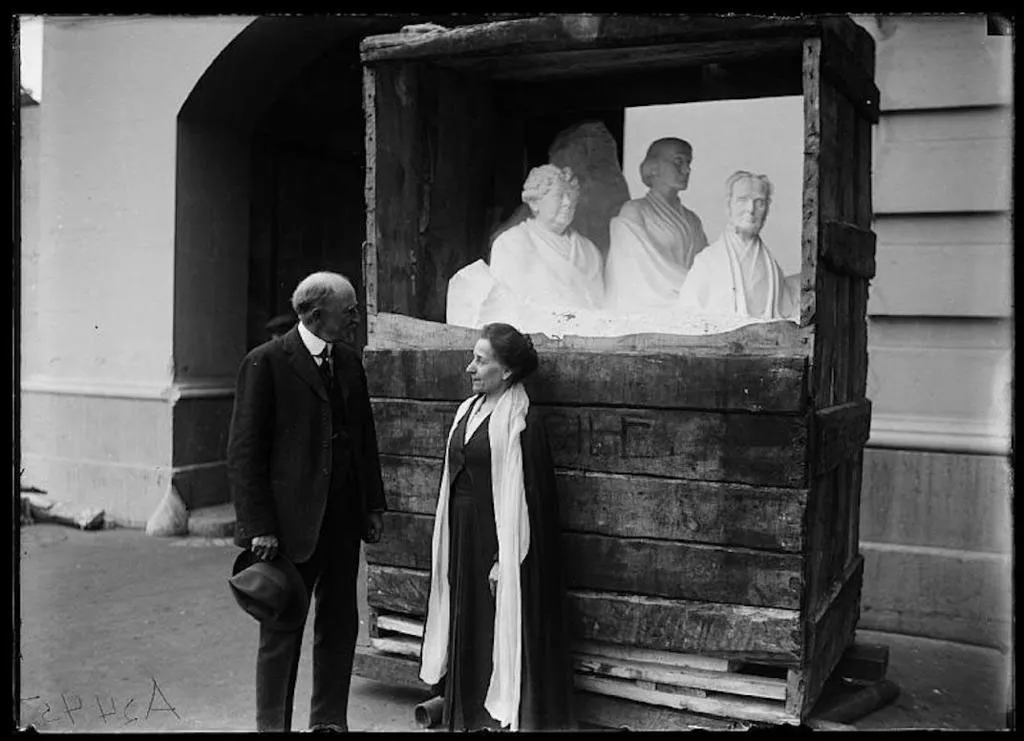

The crowd gathered around the Portrait Monument, which showed Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott in towering white marble. All three women were suffragists in the 1800s; none of them lived to see women achieve enfranchisement. But on that day in 1921, with their statue gleaming and a gilt inscription proclaiming, “Woman first denied a soul, then called mindless, now arisen, declaring herself an entity to be reckoned,” it seemed as if their work was being honored and recognized.

Until the very next day, when the statue was moved underground. Congress also ordered the inscription be scraped off.

“The crypt was originally intended for Washington’s remains, though it never housed them,” says Joan Wages, the president and CEO of the National Women’s History Museum. “At the time it was a service closet, with brooms and mops and the suffrage statue.”

On multiple occasions, Congress refused to approve bills that would’ve brought the statue back into the light. After three such unsuccessful attempts, the Crypt was cleaned up and opened to the public in 1963. Visitors would see the women’s sculpture as well as other statues and a replica of the Magna Carta. But the statue still didn’t have a plaque. Visitors wouldn’t have seen any description of the sculptor who made it—a woman named Adelaide Johnson who was commissioned by the National Woman’s Party and accepted a contract that barely covered the cost of materials—or who it portrayed.

“[Congress] consistently had the same objections. It was ugly, it weighed too much, it was too big. It was mockingly called ‘The Women in the Bathtub,’” Wages says. The nickname came from the three busts emerging from uncut marble, with a fourth uncarved pillar behind them meant to represent all the women who might continue fighting for women’s rights. Its rough, unfinished look was meant to suggest that the fight for feminism was also unfinished—a point proved by the battle over the statue itself.

Upon the 75th anniversary of the 19th amendment in 1995, women’s groups, with the bipartisan support of female members of Congress, renewed the effort to bring the statue out of storage. Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, a Democrat from New York, even began circulating a newsletter poking fun at the various excuses being used to prevent it from being moved, which included such tongue-in-cheek reasons as “We can’t move it because the next thing you know, they’ll want us to pass the [Equal Rights Amemdment]” and “They don’t have a ‘get out of the basement free’ card.” In a separate incident, Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder responded to aesthetic criticisms that the statue was ugly, “Have you looked at Abraham Lincoln lately?” Wages says.

When a resolution finally gained bipartisan support in the House and the Senate, there were still two hurdles to overcome: whether the statue was, in fact, too heavy to be supported by the Rotunda, and who would pay the estimated $75,000 required to move it. Even though Speaker Newt Gingrich was the chairman of the Capitol Preservation Commission, which had a $23 million budget to use for maintenance and acquisitions around the Capitol, he rejected a petition to use those funds for the Portrait Monument. So the groups set about raising the funds themselves. Meanwhile, a survey by the Army Corps of Engineers determined that the seven-ton sculpture wouldn’t break through the floor of the Rotunda.

On May 14, 1997, the statue was finally moved back to the Rotunda using money raised from donors around the country. The statue is still there today, next to a John Trumball painting and a statue of Lincoln. Wages, who spent much of her career in the airline industry, was among the women assembled for the event. “It had been raining all that morning, and when the statue moved in the sun broke through, like something out of a Cecil B. DeMille film. We were all cheering and crying and it was very thrilling,” Wages says. “Our works was a drop in the bucket compared to what these three women did. It was time they be recognized.”

“[The statue] was the beginning of the entire process of eventually building a museum,” says Susan Whiting, chairman of the board for the NWHM, which has the approval of a congressional commission and is seeking funds to become a full-fledged museum. “In terms of recognizing past contributions and understanding many of the stories captured in history, I don’t think things have changed anywhere near enough.”

The problem of visible representation has been noted on numerous occasions. There are the 100 statues in Statuary Hall, a room in the Capitol where two statues of prominent citizens come from each state. Only nine depict women. No park in Chicago has a statue of women, reported the local NPR affiliate in 2015, and just five of the hundreds of statues across New York City portray historic women, according to CityLab. A survey of outdoor sculpture portraits across the country found that only 10 percent portrayed historical women figures, and of the 152 National Monuments listed by the National Park Service, only three are dedicated to historic female figures.

But with the Portrait Monument celebrating its 20th year of being out in the world, there’s plenty of reason for optimism. “The Rotunda is the heart of our nation,” Wages says. “When it’s filled with statues of men, it gives an inaccurate view of who we are as a nation. It undermines women’s role. They’ve given birth to our nation, literally and figuratively.”

For what it’s worth, the statue still doesn’t have the gilt inscription.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)