Sunday Funnies Blast Off Into the Space Age

When Dr. Athelstan Spilhaus met President Kennedy in 1962, JFK told him, “The only science I ever learned was from your comic strip.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201201271131061961-oct-15-470x251.jpg)

When Dr. Athelstan Spilhaus met President Kennedy in 1962, JFK told him, “The only science I ever learned was from your comic strip in the Boston Globe.”

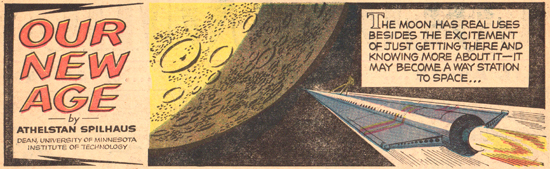

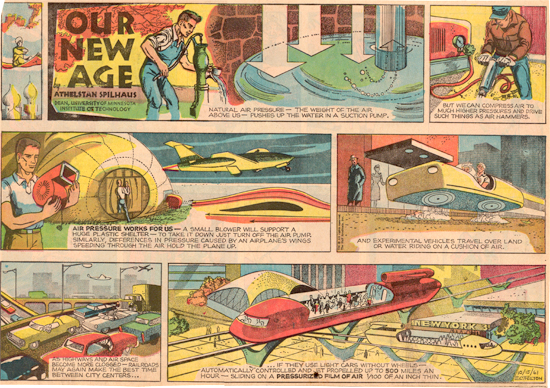

The comic strip that Kennedy was referring to was called “Our New Age” and ran in about 110 Sunday newspapers all around the world from 1958 until 1975. Much like Arthur Radebaugh‘s mid-century futurism comic “Closer Than We Think,” which ran from 1958 until 1963, “Our New Age” was a shining example of techno-utopian idealism. Not all of the strips were futuristic, but they all had that particular brand of optimism that so characterized postwar American thinking about science and technology.

Detail from the January 10, 1965 edition of the Sunday comic "Our New Age"

Each week the strip had a different theme, illustrating a scientific principle or advancement in an easily digestible way. Some of the strips tackled straightforward scientific topics like meteors and volcanoes, while others explained the latest scientific developments in synthetic fibers, space travel and lasers. The strip seemed to say that the building blocks of the future were laid out before us, we just had to build it.

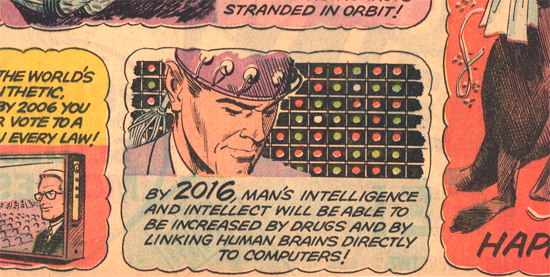

Detail from the December 26, 1965 edition of the Sunday comic strip "Our New Age"

Athelstan Spilhaus wrote “Our New Age” from its inception until 1973, but it went through three different illustrators: first Earl Cros, then E.C. Felton, then Gene Fawcette. I have a strip from 1975 (when Fawcette is still credited as the illustrator) but after Spilhaus stopped doing the strip in 1973 the identity of the writer was unclear.

As Spilhaus tells it, he was inspired to start the comic strip in October of 1957 after the Soviets launched Sputnik — the first human-made satellite — into space. He was concerned that American kids weren’t showing enough interest in science and technology. “Rather than fight my own kids reading the funnies, which is a stupid thing to do, I decided to put something good into the comics, something that was more fun and that might give a little subliminal education,” he said.

“Our New Age” had an enormous audience almost immediately. A 1959 article in Time magazine noted that the strip appeared in 102 U.S. and 19 foreign newspapers.

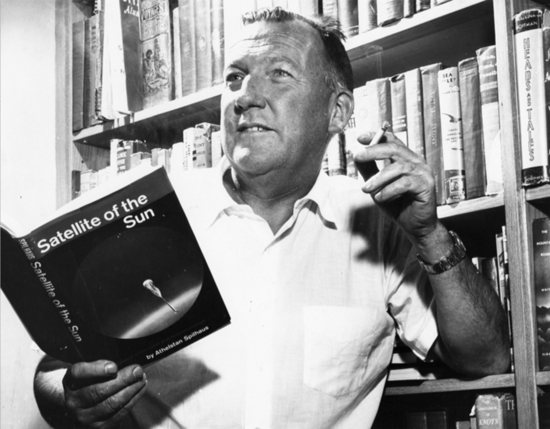

Athelstan Spilhaus in his office at the University of Minnesota (photo courtesy of Sharon Moen)

Athelstan Spilhaus was a flamboyant and remarkable futurist who led quite an extraordinary life. He was the first Unesco ambassador to the UN, started the National Sea Grant Program, was the inventor of the bathythermograph, was involved with the infamous “Roswell incident” when his Project Mogul weather balloons crashed, and even tried to get an experimental city built in Minnesota with Buckminster Fuller. The Minnesota Experimental City (MXC) never got off the ground for a number of reasons, not least of which because Spilhaus and Fuller had some major disagreements about the project.

During the majority of the time that he was writing “Our New Age,” Dr. Spilhaus was the dean of the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Technology. While in Minnesota, Spilhaus became good friends with another under-appreciated futurist thinker, journalist Victor Cohn. People were constantly asking Spilhaus, a jet-set man who had his hand in everything, how he could be involved in so many seemingly disparate projects. He told his friend Victor, “…I don’t do ‘so many things.’ I do one. I think about the future.”

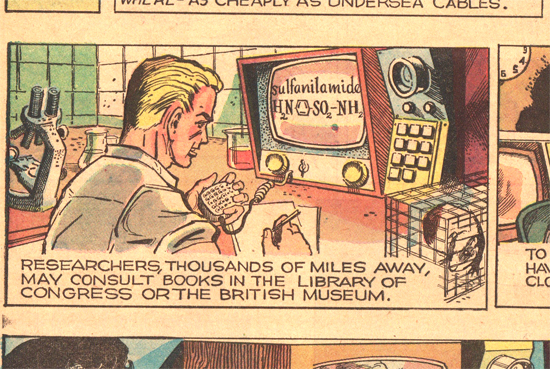

Connecting to libraries of the future as imagined in the February 19, 1962 edition of "Our New Age"

Sharon Moen at the University of Minnesota is currently writing a book about Spilhaus, due out this fall. I spoke with her on the phone.

Having been born and raised in Minnesota, I was personally interested to hear that Spilhaus was involved in the creation of the skyway system in Minneapolis and St. Paul. (The skyway system is a sort of a 2nd floor human habitrail that links many of the buildings downtown and allows pedestrians to stay indoors during the winters, rather than brave the cold at street level.) Skyways had been tried in other cities, though not on such a large scale as Spilhaus had envisioned. “Athelstan had a lot of big ideas. And one of the things that he was amazing at was taking ideas and re-applying them,” Moen told me.

Kennedy named Spilhaus the U.S. commissioner to the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. Moen told me that an early idea for the fair’s theme (before Spilhaus was brought on board) involved a “wild west” motif. But just as Sputnik had inspired Spilhaus to start writing “Our New Age,” it seems the space race had pushed the Seattle Fair into a showcase for American futurism.

Moen explained to me how important the Seattle World’s Fair (not to mention the later fairs he consulted on) were to Spilhaus: “A lot of his thinking was solidified at the World’s Fair. It’s what got him into what cities could be and recycling and farming oceans. He was really excited about the future.”

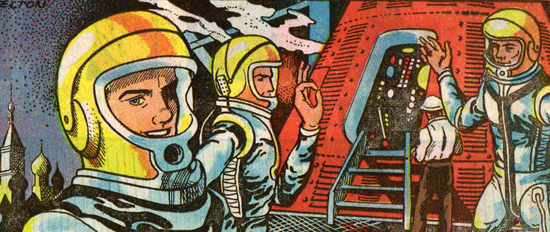

E. C. Felton's illustration of astronauts in the future (November 26, 1961 "Our New Age")

The December, 1971 issue of Smithsonian magazine published a profile on Dr. Spilhaus and mentioned that some weren’t so pleased that a distinguished academic was writing Sunday comic strips. The articles notes that his writing “Our New Age” was, “thought by some an undignified avocation.”

Dignified or not, there’s no question that influencing an American president, and reaching a worldwide audience with a message promoting science was no small feat. Spilhaus himself responded to the academics who questioned his supposedly undignified side project: “Which of you has a class of five million every Sunday morning?”

The October 14, 1961 edition of "Our New Age"

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)