The Surprising Raucous Home Life of the Madisons

One of America’s founding families kept their true selves for the friends and family

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/d0/f5d0ac2b-e0fa-4781-9109-17c3d862165b/james_dolley_madison_collage.jpg)

She looked like royalty, or so thought many guests at the sight of Dolley Madison in her velvet inaugural gown and velvet and white satin turban with towering bird-of-paradise feathers. In full naval regalia, the head of the Navy Yard led her into the hall at Long’s Hotel, followed by her husband (the new president) and her sister Anna.

Taller, broader and far more conspicuous than her husband, Dolley set to her evening’s task of charming the assembled throng. Always ready with a smile and a warm greeting, Dolley steered conversations with a steady hand, taking special care to set at ease those who appeared most uncomfortable.

For husband James, the event was just one more social occasion on which his wife would shine while he stiffly observed the proprieties. Those who met him at such gatherings invariably thought him a cold fish. One congressional wife dismissed James as a “gloomy, stiff creature . . . who has nothing engaging or even bearable in his manners – the most unsociable creature in existence.”

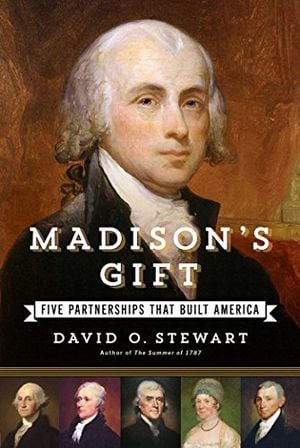

Madison’s official portraits reinforce the sober image. In earlier paintings, Madison gazes levelly out of the canvas, virtually daring the viewer to try to make him crack a grin. As Madison aged, the years shaped his face into harsh crags and furrows, creating a visage that became forbidding.

Dolley’s portraits, in contrast, show a woman with merry eyes who is suppressing a laugh. That impish look shines through the only surviving photograph of her, a daguerreotype taken at age 80, in the last year of her life.

Yet when it comes to the Madisons’ temperament, history conceals far more than it reveals. With family and close friends, they were as fun-loving a couple – even rowdy – as ever occupied the White House.

Their life together began with a passionate courtship by a man who led the Republican members of Congress in 1794. Though he did not marry until past 40, James’ interest in the opposite sex was consistent. He pursued several women in his bachelor days, ranging from a teenager half his age (who jilted him) to a wealthy widow of a Tory merchant.

Then, on a street in Philadelphia, he saw Dolley Todd, a recent widow. He flashed into action, promptly determining who she was and that his college friend, Aaron Burr, rented a room from Dolley’s mother. Burr agreed to introduce Madison to the young widow.

After a few weeks of avid courting, James recruited Dolley’s cousin to write to Dolley on his behalf. In a note that he approved “with sparkling eyes,” the cousin wrote that James “thinks so much of you in the day that he has lost his tongue, at night he dreams of you and starts in his sleep calling on you to relieve his flame for he burns to such an excess that he will be shortly consumed.”

Marriage ended neither their romance nor James’ stylized coquetry. Nearly ten years later, he sent his love to Dolley in a letter, adding “a little smack” for one of their friends, “who has a sweet lip, though I fear a sour face for me.” A note from that friend, he wrote, “makes my mouth water.” Another time he sent a kiss to the same woman and told Dolley to “accept a thousand for yourself.” After Dolley’s sister Lucy moved out of the White House, she reminded Dolley how “when he kisses you—he was always so fearful of making my mouth water.”

The future president was not only a romantic, but a high-spirited one.

Start with the wine, which James usually did. One dinner guest reported that James spent the hour after the meal passing around different vintages “of no mean quality.” Through most mealtimes, he maintained a steady stream of anecdotes and stories.

Friends relished his wicked sense of humor. His conversation, one niece recalled, moved “from brilliant mirth through to brilliant mirth.” A British diplomat found him a “jovial and good-humored companion.” Another source called James “an incessant humorist” who “set his table guests daily into roars of laughter over his stories and whimsical ways of telling them.”

Alas, the surviving samples of Madisonian humor incline more towards whimsy than hilarity. Dolley, however, was known more for warm cheer and high spirits than for incisive wit. She was, a niece recalled after her death, “a foe to dullness.”

Indeed, the Madison household rarely resembled the quiet, contemplative environment that a great thinker and leader might crave. At the White House and at Montpelier, James’ Virginia plantation, young relations and friends’ children usually overran the Madisons. The headcount at the dinner table often exceeded 20, including Dolley’s son from her first marriage, Payne Todd.

Two of Dolley’s sisters, Lucy and Anna lived with them for periods that stretched for years, along with their eight children. Dolley’s brother settled near Montpelier with his eight offspring, as did several of James’ siblings. The nieces, nephews and other kin (over 50 between James and Dolley) were legion. Then came James’ relations in central Virginia’s Orange County and Dolley’s ten cousins, two of whom served as James’ aides as president.

At Montpelier and the White House, the constant presence of younger generations meant that the patriarch and matriarch never took themselves too seriously. Upon receiving stockings too small for her generous proportions, she reported that “the hose will not fit even my darling little husband.” When Dolley challenged a young girl to a footrace, she assured her that “Madison and I often run races here.” A house guest reported that the former first couple, “sometimes romp and tease each other like two children.”

The guest added that Dolley, who was “stronger as well as larger than he,” sometimes “could – and did – seize his hands, draw him upon her back, and go round the room with him.” We are left to imagine the accompanying shrieks and laughter.

Take another look at those portraits of the Madisons. Behind the solemn expressions, perhaps you can make out the joking, passionate man and his fun-loving wife.