Ted Sorensen on Abraham Lincoln: A Man of His Words

Kennedy advisor Ted Sorensen found that of all the U.S. presidents, Lincoln had the best speechwriter—himself

Abraham Lincoln, the greatest American president, was also in my view the best of all presidential speechwriters. As a youngster in Lincoln, Nebraska, I stood before the statue of the president gracing the west side of the towering state capitol and soaked up the words of his Gettysburg Address, inscribed on a granite slab behind the statue.

Two decades later, in January 1961, President-elect John F. Kennedy asked me to study those words again, in preparing to help him write his inaugural address. He also asked me to read all previous 20th-century inaugural addresses. I did not learn much from those speeches (except for FDR's first inaugural), but I learned a great deal from Lincoln's ten sentences.

Now, 47 years later, as another tall, skinny, oratorically impressive Illinois lawyer is invoking Lincoln as he pursues his own candidacy for president, and with Lincoln's bicentennial underway (he turns 200 February 12, 2009), I want to acknowledge my debt.

Lincoln was a superb writer. Like Jefferson and Teddy Roosevelt, but few if any other presidents, he could have been a successful writer wholly apart from his political career. He needed no White House speechwriter, as that post is understood today. He wrote his major speeches out by hand, as he did his eloquent letters and other documents. Sometimes he read his draft speeches aloud to others, including members of his cabinet and his two principal secretaries, John Hay and John Nicolay, and he occasionally received suggestions, particularly at the start of his administration, from his onetime rival for the presidency, Secretary of State William Seward. On the first occasion on which Seward offered a major contribution—Lincoln's first inaugural—the president demonstrated clearly that he was the better speechwriter. Seward's idea was worthy, principally a change in the ending, making it softer, more conciliatory, invoking shared memories. But his half-completed proposed wording, often cited by historians, was pedestrian: "The mystic chords which proceeding from so many battle fields and so many patriot graves pass through all the hearts . . . in this broad continent of ours will yet again harmonize in their ancient music when breathed upon by the guardian angel of the nation."

Lincoln graciously took and read Seward's suggested ending, but, with the magic of his own pen, turned it into his moving appeal to "the mystic chords of memory," which, "stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

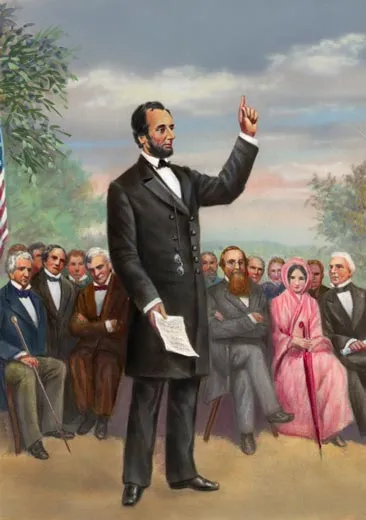

Lincoln was a better speechwriter than speaker. Normally, the success of a speech depends in considerable part on the speaker's voice and presence. The best speeches of John F. Kennedy benefited from his platform presence, his poise, personality, good looks and strong voice. William Jennings Bryan moved audiences not only with the extravagance of his language, but also with the skill of his movements and gestures, the strength of his voice and appearance. Democratic Party leaders not attending the 1896 National Convention at which Bryan delivered his "Cross of Gold" speech, and thus not carried away by the power of his presence, later could not understand his nomination on the basis of what they merely read. Franklin Roosevelt's speeches, for those who were not present for his performance, were merely cold words on a page with substantially less effect than they had for those who were present to hear them.

But Lincoln's words, heard by comparatively few, by themselves carried power across time and around the world. I may have been more moved by his remarks at the Gettysburg cemetery when I read them behind his statue at the state capitol in Lincoln in 1939 than were some of those straining to hear them on the outskirts of the audience at Gettysburg in 1863. The Massachusetts statesman Edward Everett, with his two-hour speech filled with classical allusions, had been the designated orator of the day. The president was up and quickly down with his dedicatory remarks in a few short minutes. Some newspapers reported: "The President also spoke."

Lincoln's voice, reportedly high, was not as strong as Bryan's, nor were his looks as appealing as Kennedy's. (Lincoln himself referred to his "poor, lean, lank face.") His reading was not electronically amplified nor facilitated by a teleprompter, which today almost every president uses to conceal his dependence on a prepared text. (Why? Would we have more confidence in a surgeon or a plumber who operated without referring to his manual? Do we expect our presidents to memorize or improvise their most important speeches?) Lincoln also spoke with a Midwestern inflection that—in those days, before mass media created a homogenized national audience and accent—was not the way folks talked in Boston or New York, making him difficult for some audiences to understand.

But Lincoln's success as an orator stemmed not from his voice, demeanor or delivery, or even his presence, but from his words and his ideas. He put into powerful language the nub of the matter in the controversy over slavery and secession in his own time, and the core meaning for all time of this nation itself as "this last best hope of earth." Such great and moving subjects produce many more great and moving speeches than discussions of tax cuts and tariffs.

With his prodigious memory and willingness to dig out facts (as his own researcher), he could offer meticulous historical detail, as he demonstrated in his antislavery Peoria speech of 1854 and in the 1860 Cooper Union address, which effectively secured for him the Republican nomination for president. But most Lincoln speeches eschewed detail for timeless themes and flawless construction; they were profound, philosophical, never partisan, pompous or pedantic. His two greatest speeches—the greatest speeches by any president—are not only quite short (the second inaugural is just a shade over 700 words, the Gettysburg Address shorter still), but did not deal in the facts of current policy at all, but only with the largest ideas.

A president, like everyone else, is shaped by his media environment, and if he is good, he shapes his communication to fit that environment. Lincoln lived in an age of print. Oratory was important political entertainment; but with no broadcasting, his words reached large audiences outside the immediate vicinity only by print. His speeches were published in the newspapers of the day and composed by him with that in mind. He spoke for readers of the printed page, not merely for those listening. His words moved voters far from the sound of his voice because of his writing skills, his intellectual power, his grip on the core issue of his time and his sublime concept of his nation's meaning.

Franklin Roosevelt mastered the fireside chat on radio, Kennedy the formal address on television, Bill Clinton the more casual messages. Of course, modern American television audiences would not tolerate the three-hour debates Lincoln had with Stephen Douglas, or his longer speeches—but that was a different age. Lincoln was adaptable enough that he could have mastered modern modes of political speech—today's sound-bite culture—had he lived in this era. He had a talent for getting to the point.

Lincoln avoided the fancy and artificial. He used the rhetorical devices that the rest of us speechwriters do: alliteration ("Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray"; "no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet"); rhyme ("I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views"); repetition ("As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew"; "We cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground"); and—especially—contrast and balance ("The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present"; "As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master"; "In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free").

He used metaphors, as we all do, both explicit and implicit: think of the implied figure of birth—the nation "brought forth," "conceived"—in the Gettysburg Address. He would quote the Bible quite sparingly, but to tremendous effect. See how he ends the monumental next-to-last paragraph of the second inaugural: "Yet, if God wills that [the Civil War] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘the judgments of the Lord are True and Righteous Altogether.' "

But the triumph of this greatest example of American public speech did not come from devices alone. Lincoln had in addition two great qualities infusing his use of those devices. First, he had a poetic literary sensibility. He was aware of the right rhythm and sound. An editor of the Gettysburg Address might say that "Eighty-seven years ago" is shorter. Lincoln wrote instead, "Four score and seven years ago."

And, finally, he had the root of the matter in him. The presidents greatest in speechcraft are almost all the greatest in statecraft also—because speeches are not just words. They present ideas, directions and values, and the best speeches are those that get those right. As Lincoln did.

Theodore C. Sorensen, former special counsel to President John F. Kennedy, is the author, most recently, of Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History.