The Curious Case of Nashville’s Frail Sisterhood

Finding prostitutes in the Union-occupied city was no problem, but expelling them was

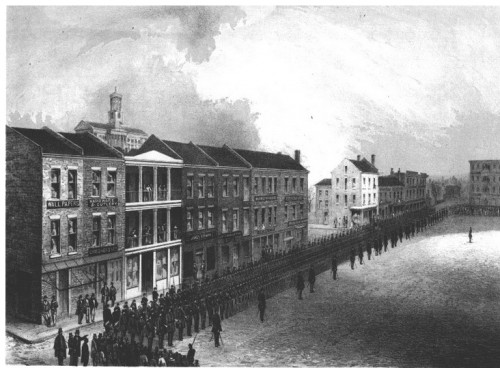

Nashville under Union occupation, c. 1863. Library of Congress

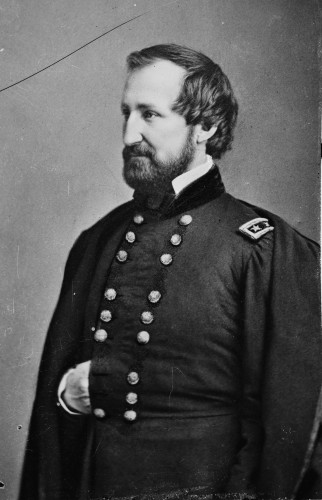

Major General William Rosecrans, leader of the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, had a problem.

“Old Rosy,” as he’d been nicknamed at West Point, was a handsome Ohio-born history buff and hobbyist inventor with a reputation for getting nearer to combat than any other man of his rank. He had led his troops to a series of victories in the Western theater, and by 1863 he was, after Ulysses S. Grant, the most powerful man in the region. Rosecrans’ men were spending a great deal of time in Nashville, a city that had fallen to the Union in February 1862.

The major general thought Nashville was a good place for his troops to gather strength and sharpen their tactical abilities for the next round of fighting, but he underestimated the lure of the city’s nightlife.

According to the 1860 U.S. Census, Nashville was home to 198 white prostitutes and nine referred to as “mulatto.” The city’s red-light district was a two-block area known as “Smoky Row,” where women engaged in the sex trade entertained farmers and merchants in town on business.

By 1862, though, the number of “public women” in Nashville had increased to nearly 1,500, and they were always busy. Union troops a long way from home handed their meager paychecks over to brothel keepers and street walkers with abandon, and by the spring of 1863, Rosecrans and his staff were in a frenzy over the potential impact of all that cavorting. But Rosencrans, a Catholic, wasn’t worried about mortal sin. He was worried about disease.

Syphilis and gonorrhea, infections spread through sexual contact, were almost as dangerous to Civil War soldiers as combat. At least 8.2 percent of Union troops would be infected with one or the other before war’s end—nearly half the battle-injury rate of 17.5 percent, even without accounting for those who contracted a disease and didn’t know it or didn’t mention it—and the treatments (most involved mercury), when they worked, could sideline a man for weeks.

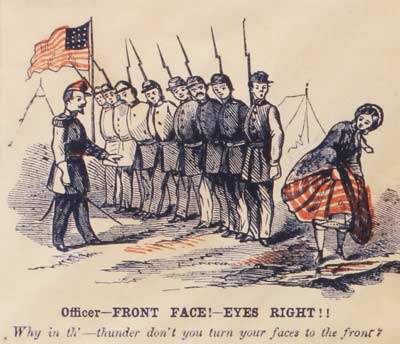

Union officials in Nashville, certain the city’s ladies of the night were responsible for the sexual plague, hit upon what seemed like the simplest solution: If they couldn’t stop soldiers from visiting local prostitutes, local prostitutes could simply be made non-local.

In the first days of July 1863, Rosecrans issued an order to George Spalding, provost marshal of Nashville, to “without loss of time seize and transport to Louisville all prostitutes found in the city or known to be here.”

The dutiful Spalding, a Scottish immigrant who’d spent the prewar years teaching school in a Michigan town on the shore of Lake Erie, began carrying out the order, and on July 9, the Nashville Daily Press reported, the roundup of the “sinful fair” began, though not without some protest and maneuvering on the part of targeted women:

A variety of ruses were adopted to avoid being exiled; among them, the marriage of one of the most notorious of the cyprians to some scamp. The artful daughter of sin was still compelled to take a berth with her suffering companions, and she is on her way to banishment.

Finding Nashville prostitutes was easy, but how was Spalding to expel them? He hit upon the answer by the second week in July, when he met John Newcomb, owner of a brand-new steamboat recently christened the Idahoe. To Newcomb’s horror, Spalding (backed by Rosecrans and other officials) ordered Newcomb to take the Idahoe on a maiden voyage northward (ideally to Louisville, but Spalding wasn’t particular) with 111 of Nashville’s most infamous sex workers as passengers. Newcomb and his crew of three were given rations enough to last the passengers to Louisville, but otherwise they were on their own. The local press delighted in the story, encouraging readers to “bid goodbye to those frail sisters once and for all.”

For many Civil War-era women, prostitution was an inevitability, especially in the South, where basic necessities became unaffordable on the salaries or pensions of enlisted husbands and fathers. Urban centers had long played host to prostitutes catering to every social class (an estimated 5,000 prostitutes worked in the District of Columbia in 1864, and an estimated three to five percent of New York City women sold sex at one time or another), and an enterprising prostitute working in a major city could earn almost $5 a week, more than three times what she might be able to bring in doing sewing or other household labor. While some prostitutes adopted the sex trade as a lifelong occupation, for many it was interstitial, undertaken when money was tight and observation by friends or family might be evaded.

Little is known about the prostitutes banished from Nashville, though it’s likely they were already known to officials of the law or had been accused of spreading venereal diseases. All 111 women aboard the Idahoe had one thing in common: their race. The women heading for points north were all white. And almost immediately upon their departure, their black counterparts took their places in the city’s brothels and its alleys, much to the chagrin of the Nashville Daily Union:

The sudden expatriation of hundreds of vicious white women will only make room for an equal number of negro strumpets. Unless the aggravated curse of lechery as it exists among the negresses of the town is destroyed by rigid military or civil mandates, or the indiscriminate expulsion of the guilty sex, the ejectment of the white class will turn out to have been productive of the sin it was intended to eradicate…. We dare say no city in the country has been more shamefully abused by the conduct of its unchaste females, white and Negro, than has Nashville for the past fifteen or eighteen months.

It took a week for the Idahoe to reach Louisville, but word of the unusual manifest list had reached that city’s law enforcement. Newcomb was forbidden from docking there and ordered on to Cincinnati instead. Ohio, too, was uneager to accept Nashville’s prostitutes, and the ship was forced to dock across the river in Kentucky—with all inmates required to stay on board, reported the Cincinnati Gazette:

There does not seem to be much desire on the part of our authorities to welcome such a large addition to the already overflowing numbers engaged in their peculiar profession, and the remonstrances were so urgent against their being permitted to land that that boat has taken over to the Kentucky shore; but the authorities of Newport and Covington have no greater desire for their company, and the consequence is that the poor girls are still kept on board the boat. It is said (on what authority we are unable to discover) that the military order issued in Nashville has been revoked in Washington, and that they will all be returned to Nashville again.

A few, according to the Cleveland Morning Leader, which rapturously chronicled the excitement happening across the state, tried to swim ashore, while others were accused of trying to make contact with Confederate forces who might help them escape. The women, according to reports, were in bad shape:

The majority are a homely, forlorn set of degraded creatures. Having been hurried on the boats by a military guard, many are without a change of wardrobe. They managed to smuggle a little liquor on board, which gave out on the second day. Several became intoxicated and indulged in a free fight, which resulted without material damage to any of the party, although knives were freely used.

Desperate to get the remaining 98 women and six children off his ship, Newcomb returned the Idahoe to Louisville, where it was once again turned away, and by early August the Cincinnati Gazette was proven correct—the ship returned to Nashville, leaving Spalding exactly where he’d started, plus with a hefty bill from Newcomb. Demanding compensation for damages to his ship, Newcomb insisted someone from the Army perform an inspection. On August 8, 1863, a staffer reporting to Rosecrans found that the ship’s stateroom had been “badly damaged, the mattresses badly soiled,” and recommended Newcomb be paid $1,000 in damages, plus $4,300 to cover the food and “medicine peculiar to the diseased of women in this class” the Idahoe’s owner had been forced to pay for during the 28-day excursion.

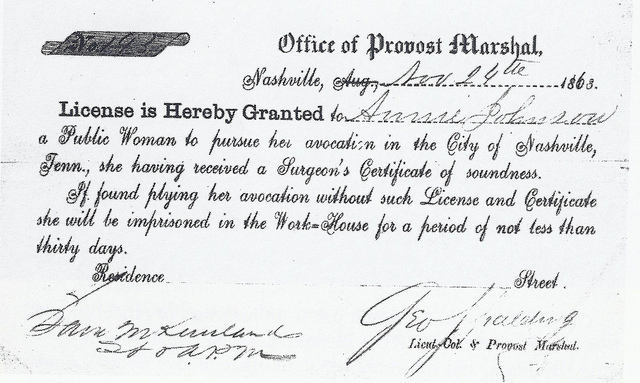

George Spalding was unconcerned with Newcomb’s hardships. His plan to rid the city of cyprians had failed. Resigning himself to the fact that prostitutes would ply their trade and soldiers would engage them, he reasoned that the women might as well sell sex safely, and so out of sheer desperation, Spalding and the Union Army created in Nashville’s the country’s first system of legalized prostitution.

Spalding’s proposal was simple: Each prostitute would register herself, obtaining for $5 a license entitling her to work as she pleased. A doctor approved by the Army would be charged with examining prostitutes each week, a service for which each woman would pay a 50 cent fee. Women found to have venereal diseases would be sent to a hospital established (in the home of the former Catholic bishop) for the treatment of such ailments, paid for in part by the weekly fees. Engaging in prostitution without a license, or failing to appear for scheduled examinations, would result in arrest and a jail term of 30 days.

The prospect of participating in the sex trade without fear of arrest or prosecution was instantly attractive to most of Nashville’s prostitutes, and by early 1864 some 352 women were on record as being licensed, and another hundred had been successfully treated for syphilis and other conditions hazardous to their industry. In the summer of 1864, one doctor at the hospital remarked on a “marked improvement” in the licensed prostitutes’ physical and mental health, noting that at the beginning of the initiative the women had been characterized by use of crude language and little care for personal hygiene, but were soon virtual models of “cleanliness and propriety.”

A New York Times reporter visiting Nashville was equally impressed, noting that the expenses of the program from September 1863 to June totaled just over $6,000, with income from the taxes on “lewd women” reached $5,900. Writing several years after war’s end, the Pacific Medical Journal argued that legalized prostitution not only helped rid Rosecrans’ army of venereal disease, it also had a positive impact on other armies (a similar system of prostitution licensing was enacted in Memphis in 1864):

The result claimed for the experiment was that in Gen. Sherman’s army of 100,000 men or more, but one or two cases were known to exist, while in Rosecrans’ army of 50,000 men, there had been nearly 1500 cases.

Once fearful of the law (particularly the military law, given the treatment they’d received), Nashville prostitutes took to the system with almost as much enthusiasm as those operating it. One doctor wrote that they felt grateful to no longer have to turn to “quacks and charlatans” for expensive and ineffective treatments, and eagerly showed potential customers their licenses to prove that they were disease-free.

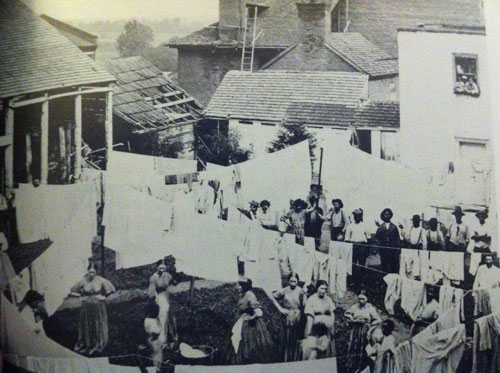

Nashville women in what was likely the hospital for infected prostitutes, c. 1864. From Thomas Lowry’s The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War.

Regulated sex commerce in Nashville was short-lived. After the war ended, in 1865, and the city was no longer under the control of the Union army, licenses and hospitals quickly faded from public consciousness. Today, the handful of U.S. counties that allow prostitution, such as Nevada’s Lyon County, rely on a regulatory system remarkably similar to the one implemented in 1863 Nashville.

Rosecrans, after making a tactical error that cost the Union army thousands of lives at the Battle of Chickamauga, was relieved of his command by Grant; he finished the war as commander of the Department of Missouri. After the war he took up politics, eventually representing a California district in Congress in the 1880s. (In the ’90s, Spalding would follow the congressional path, representing a Michigan district.)

One man who had a bit more difficulty moving on from the summer of 1863 was John Newcomb. Nearly two years after the Idahoe made its infamous voyage, he still hadn’t been reimbursed by the government. Out of frustration, he submited his claim directly to Edward Stanton, Secretary of War, after which he was furnished with the money he was owed and certification that the removal of the Nashville prostitutes had been “necessary and for the good of the service.”

Even after collecting nearly $6,000, Newcomb knew the Idahoe would never again cruise the rivers of the Southeastern United States. “I told them it would forever ruin her reputation as a passenger boat”, he told officials during one of his attempts to be compensated. “It was done, so she is now & since known as the floating whore house.”

Sources

Books: Butler, Anne, Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery, University of Illinois Press, 1987; Lowry, Thomas, The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War, Stackpole Press, 1994; Clinton, Catherine, “Public Women and Sexual Politics During the American Civil War, in Battle Scars: Gender and Sexuality in the American Civil War, Oxford University Press, 2006; Denney, Robert, Civil War Medicine, Sterling, 1995; Massey, Mary, Women in the Civil War, University of Nebraska Press, 1966.

Articles: “A Strange Cargo,” Cleveland Morning Leader, July 21, 1863; “George Spalding,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress; “William Rosecrans,” Civil War Trust; “The Cyprians Again,” Nashville Daily Press, July 7, 1863; “Round Up of Prostitutes,” Nashville Daily Press, July 9, 1863; “News from Cincinnati,” Nashville Daily Union, July 19, 1863; “Black Prostitutes Replace White Prostitutes in Occupied Nashville,” Nashville Daily Press, July 10, 1863; “Some Thoughts about the Army,” New York Times, September 13, 1863; Goldin, Claudia D. and Frank D. Lewis, “The Economic Cost of the American Civil War: Estimates and Implications,” Journal of Economic History, 1975.