The Death of Colonel Ellsworth

The first Union officer killed in the Civil War was a friend of President Lincoln’s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-at-Hand-Elmer-Ellsworth-631.jpg)

One of the quieter commemorations of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War—but one of the most intriguing—can soon be found in an alcove at the end of a main hallway at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in Washington, D.C. Between two rooms housing highlights of the museum’s Civil War collection, a new exhibition, “The Death of Ellsworth,” revisits a once-famous but now largely forgotten incident. The exhibition opens April 29.

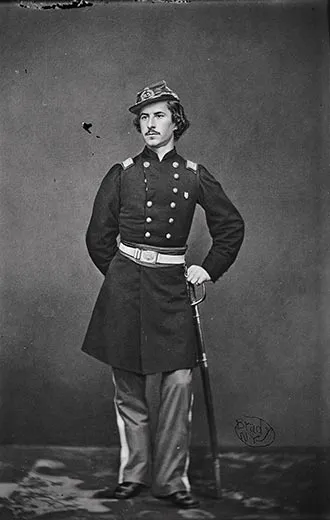

The focal object is a 3 3/8- by 2 3/16-inch photograph of Union Army Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, a dashing figure, his left hand resting on the hilt of his saber. James Barber, the NPG historian who curated the exhibition, describes the portrait as “one of the gems of our story of the war.”

The image was taken around 1861 by an unknown portraitist in the New York studio of Mathew Brady, the photographer who would become indelibly associated with Civil War images. The photograph is a print from an original glass negative purchased by the NPG in 1981.

Ellsworth was a man with large military ambitions, but his meteoric fame came in a way he could not have hoped for: posthumously. At the age of 24, as commander of the 11th New York Volunteers, also known as the First Fire Zouaves, Ellsworth became the first Union officer killed in the war.

He was not just any Union officer. After working as a patent agent in Rockford, Illinois, in 1854, Ellsworth studied law in Chicago, where he also served as a colonel commanding National Guard cadets. In 1860, Ellsworth took a job in Abraham Lincoln’s Springfield law office. The young clerk and Lincoln became friends, and when the president-elect moved to Washington in 1861, Ellsworth accompanied him. A student of military history and tactics, Ellsworth admired the Zouaves, Algerian troops fighting with the French Army in North Africa, and had employed their training methods with his cadets. He even designed a uniform with baggy trousers in the Zouave style.

A native of New York State, Ellsworth left Washington for New York City just before the onset of the war. He raised the 11th New York Volunteer Regiment, enlisting many of its troops from the city’s volunteer fire departments (hence the “Fire Zouaves”) and returned with the regiment to Washington.

On May 24, 1861, the day after Virginia voters ratified the state convention’s decision to secede from the Union, Ellsworth and his troops entered Alexandria, Virginia, to assist in the occupation of the city. As it happened, an 8- by 14-foot Confederate flag—large enough to be seen by spyglass from the White House—had been visible in Alexandria for weeks, flown from the roof of an inn, the Marshall House.

The regiment, organized only six weeks earlier, encountered no resistance as it moved through the city. Barber notes, however, that “the Zouaves were an unruly bunch, spoiling for a fight, and when they got into Alexandria they may have felt they were already in the thick of it. So Ellsworth may have wanted to get that flag down quickly to prevent trouble.”

At the Marshall House, Barber adds, “Colonel Ellsworth just happened to meet the one person he didn’t want to meet”—innkeeper James Jackson, a zealous defender of slavery (and, says Barber, a notorious slave abuser) with a penchant for violence.

Ellsworth approached the inn with only four troopers. Finding no resistance, he took down the flag, but as he descended to the main floor, Jackson fired on Ellsworth at point-blank range with a shotgun, killing him instantly. One of Ellsworth’s men, Cpl. Francis Brownell, then fatally shot Jackson.

A reporter from the New York Tribune happened to be on the scene; news of the shootings traveled fast. Because Ellsworth had been Lincoln’s friend, his body was taken to the White House, where it lay in state, and then to New York City, where thousands lined up to view the cortege bearing Ellsworth’s coffin. Along the route, a group of mourners displayed a banner that declared: “Ellsworth, ‘His blood cries for vengeance.’”

“Remember Ellsworth!” became a Union rallying cry, and the 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment was nicknamed Ellsworth’s Avengers. According to Barber, “Throughout the conflict, his name, face and valor would be recalled on stationery, in sheet music and in memorial lithographs.” One side’s villain is another side’s patriot, of course, so Jackson was similarly celebrated in the South and in an 1862 book, Life of James W. Jackson, The Alexandria Hero.

After the war, and after relentlessly petitioning his congressman, Brownell was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article stated Brownell was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. This version has been corrected.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)