The Early History of Faking War on Film

Early filmmakers faced a dilemma: how to capture the drama of war without getting themselves killed in the process. Their solution: fake the footage

![]()

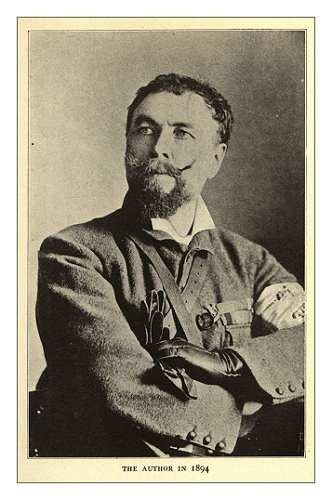

Frederic Villiers, an experienced war artist and pioneer cinematographer, was the first man to attempt to film in battle—with deeply disappointing results.

Who first thought of building a pyramid, or of using gunpowder as a weapon? Who invented the wheel? Who, for that matter, came up with the idea of taking a movie camera into battle and turning a profit from the horrible realities of war? History offers no firm guidance on the first three questions, and is not entirely certain even on the fourth, although the earliest war films cannot have been shot much earlier than 1900. What we can say, fairly definitely, is that most of this pioneer footage tells us little about war as it was actually waged back then, and quite a lot about the enduring ingenuity of filmmakers. That is because almost all of it was either staged or faked, setting a template that was followed for years afterwards with varying degrees of success.

I tried to show in last week’s essay how newsreel cameramen took on the challenge of filming the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20—a challenge they met, at one point, by signing the celebrated rebel leader Pancho Villa to an exclusive contract. What I did not explain, for lack of space, was that the Mutual Film teams embedded with Villa were not the first cinematographers to tussle with the problems of capturing live action with bulky cameras in dangerous situations. Nor were they the first to conclude that it was easier and safer to fake their footage—and that fraud in any case produced far more saleable results. Indeed, the early history of newsreel cinema is replete with examples of cameramen responding in precisely the same way to the same set of challenges. Pretty much the earliest “war” footage ever shot, in fact, was created in circumstances that broadly mirror those prevailing in Mexico.

The few historians to take an interest in the prehistory of war photography seem agreed that the earliest footage secured in a war zone dates to the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, and was shot by a veteran British war correspondent by the name of Frederic Villiers. How well he rose to the occasion is hard to say, because the war is an obscure one, and though Villiers—a notoriously self-aggrandising poseur—wrote about his experiences in sometimes hard-to-believe detail, none of the footage he claimed to have shot survives. What we can say is that the British veteran was an experienced reporter who had covered nearly a dozen conflicts during his two decades as a correspondent, and certainly was in Greece for at least a part of the 30-day conflict. He was a prolific, if limited, war artist as well, so the idea of taking one of the new ciné cameras to war probably came naturally to him.

The Battle of Omdurman, fought between British and Sudanese forces in September 1898, was one of the first to show the disappointing gap between image and reality. Top: an artist’s impression of the charge of the 21st Lancers at the height of the battle. Bottom: a photograph of the real but distant action as captured by an enterprising photographer.

If that’s so, the notion wasn’t too obvious to anyone else in 1897; when Villiers arrived at his base at Volos, in Thessaly, trailing his cinematograph and a bicycle, he discovered he was the only cameraman covering the war. According to his own accounts, he was able to get some real long-distance shots of the fighting, but the results were deeply disappointing, not least because real war bore little resemblance to the romantic visions of conflict held by the audiences of the earliest newsreels. “There was no blare of bugals,” the journalist complained on his return, “or roll of drums; no display of flags or of martial music of any sort… All had changed in this modern warfare; it seemed to me a very cold-blooded, uninspiring way of fighting, and I was mightily depressed for many weeks.”

Villiers yearned to obtain something much more visceral, and he got what he required in typically resourceful fashion, passing through the Turkish lines to secure a private interview with the Ottoman governor, Enver Bay, who granted him a safe passage to the Greek capital, Athens, which was much closer to the fighting. ”Not content with this,” writes Stephen Bottomore, the great authority on the first war films,

Villiers asked the governor for confidential information: “I want to know when and where the next fight will take place. You Turks will take the initiative, for the Greeks can now only be on the defensive.” Not surprisingly, Enver Bey was staggered by his request. Looking at Villiers steadily, he said at last: “You are an Englishman and I can trust you. I will tell you this: Take this steamer… to the port of Domokos, and don’t fail to be at the latter place by Monday noon.”

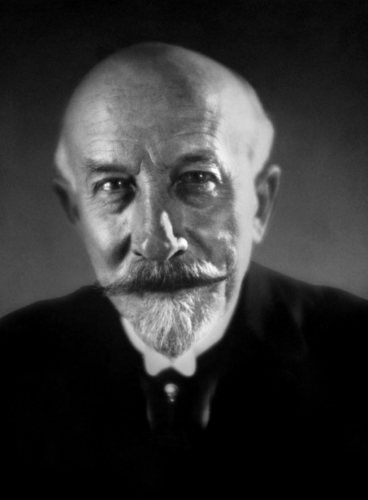

Georges Méliès, the pioneer filmmaker, shot faked footage of the war of 1897—including the earliest shots of what was claimed to be naval warfare, and some horrific scenes of atrocities in Crete. All were created in his studio or his back yard in Paris.

Armed with this exclusive information (Villiers’s own record of the war continues), he arrived at Domokos “on the exact day and hour to hear the first gun fired by the Greeks at the Moslem infantry advancing across the Pharsala plains.” Some battle scenes were shot. Since the cameraman remained uncharacteristically modest about the results of his labours, though, we may reasonably conclude that whatever footage he was able to obtain showed little if any of the ensuing action. That seems to be implicit in one revealing fragment that does survive: Villiers’s own outraged account of how he found himself out-filmed by an enterprising rival. Notes Bottomore:

The images were accurate, but they lacked cinematic appeal. When he got back to England, he realised that his footage was worth very little in the film market. One day a friend told him that he had seen some wonderful pictures of the Greek war the previous evening. Villiers was surprised since he knew for certain that he had been the only cameraman filming the war. He soon realised from his friend’s account that these were not his pictures:

“Three Albanians came along a very white dusty road toward a cottage on the right of the screen. As they neared it they opened fire; you could see the bullets strike the stucco of he building. then one of the Turks with the butt end of his rifle smashed in the door of the cottage, entered and brought out a lovely Athenian maid in his arms… Presently an old man, evidently the girl’s father, rushed out of the house to her rescue, when the second Albanian whipped out his yataghan from his belt and cut the old gentleman’s head off! Here my friend grew enthusiastic. ‘There was the head,’ said he, ‘rolling in the foreground of the picture. Nothing could be more positive than that.’”

A still from Georges Méliès’s short film “Sea Battle in Greece” (1897), clearly showing the dramatic effects and clever use of a pivoted deck, which the filmmaker pioneered.

Although Villiers probably never knew it, he had been scooped by one of the great geniuses of cinema, Georges Méliès, a Frenchman best remembered today for his special-effects-laden 1902 short “Le voyage dans la lune.” Five years before that triumph, Méliès had, like Villiers, been inspired by the commercial potential of a real war in Europe. Unlike Villiers, he had traveled no closer to the front than his back yard in Paris—but, with his showman’s instinct, the Frenchman triumphed nonetheless over his rival on the spot, even shooting some elaborate footage that purported to show close ups of a dramatic naval battle. The latter scenes, recovered a few years ago by the film historian John Barnes, are especially notable for the innovation of an “articulated set”—a pivoted section of deck designed to make it appear that Méliès’s ship was being tossed about in a rough sea, and which is still in use, barely modified, on film sets today.

Villiers himself good-humoredly admitted how difficult it was for a real newsreel cameraman to compete with an enterprising faker. The problem, he explained to his excited friend, was the unwieldiness of the contemporary camera:

You have to fix it on a tripod… and get everything in focus before you can take a picture. Then you have to turn the handle in a deliberate, coffee-mill sort of way, with no hurry or excitement. It’s not a bit like a snapshot, press-the-button pocket Kodak. Now just think of that scene you have so vividly described to me. Imagine the man who was coffee-milling saying, in a persuasive way, “Now Mr. Albanian, before you take the old gent’s head off come a little nearer; yes, but a little more to the left, please. Thank you. Now, then, look as savage as you can and cut away.” Or, “You, No. 2 Albanian, make that hussy lower her chin a bit and keep her kicking as ladylike as possible.”

D.W. Griffith, a controversial giant of the early cinema, whose undoubted genius is often set against his apparent endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan in Birth of a Nation

Much the same sort of results—”real,” long-distance battle footage trumped in the cinemas by more action-packed and visceral fake footage—were obtained a few years later during the Boxer Rebellion in China and the Boer War, a conflict fought between British forces and Afrikaaner farmers. The South African conflict set a pattern that later war photography would follow for decades (and which was famously repeated in the first feature-length war documentary, the celebrated 1916 production The Battle of the Somme, which mixed genuine footage of the trenches with fake battle scenes shot in the altogether safe environs of a trench mortar school behind the lines. The movie played to packed and uncritically enthusiastic houses for months.) Some of these deceptions were acknowledged; R.W. Paul, who produced a series of shorts depicting the South African conflict, made no claim to have secured his footage in the war zone, merely stating that they had been “arranged under the supervision of an experienced military officer from the front.” Others were not. William Dickson, of the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company, did travel to the Veldt and did produce what Barnes describes as

footage that can legitimately be described as actuality—scenes of troops in camp and on the move—though even so many shots were evidently staged for the camera. British soldiers were dressed in Boer uniforms to reconstruct skirmishes, and it was reported that the British commander-in-chief, Lord Roberts, consented to be Biographed with all his Staff, actually having his table taken out into the sun for the convenience of Mr Dickson.

Telling the fake footage of the earliest years of cinema from the real thing is never very difficult. Reconstructions are typically close-ups and are betrayed, Barnes notes in his study Filming the Boer War, because “action occurs towards and away from the camera in common with certain ‘actuality’ films of the period such as street scenes where pedestrians and traffic approach or recede along the axis of the lens and not across the field of vision like actors on a stage.” This, of course, strongly suggests a deliberate attempt at deception on the part of the filmmakers, but it would be too easy to simply condemn them for this. After all, as D.W. Griffith, another of the greatest early pioneers of film, pointed out, a conflict as vast as the First World War was “too colossal to be dramatic. No one can describe it. You might as well try to describe the ocean or the Milky Way…. No one saw a thousandth part of it.”

Edward Amet stands in front of the pool and painted backdrop used in the filming of his faked war movie The Battle of Matanzas.

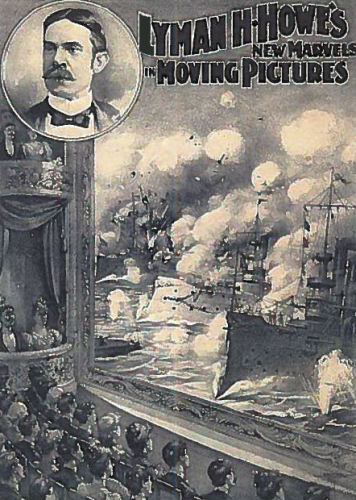

Of course, the difficulties that Griffith described, and which Frederic Villiers and the men who followed him in South Africa and China at the turn of the century actually experienced, were as nothing to the problems confronting the ambitious handful of filmmakers who turned their hands to portraying war as it is fought at sea—a notoriously expensive business, even today. Here, while Georges Méliès’s pioneering work on the Greco-Turkish War may have set the standard, the most interesting—and unintentionally humorous—clips that have survived from the earliest days of cinema are those that purport to show victorious American naval actions during the Spanish-American War of 1898.

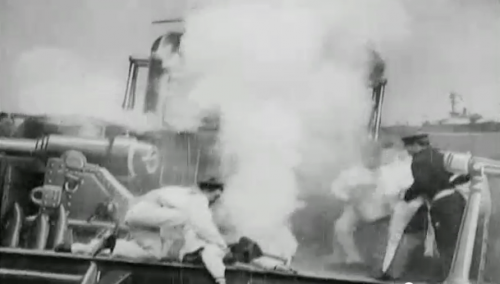

Once again, the “reconstructed” footage that appeared during this conflict was less a deliberate, malicious fake than it was an imaginative response to the frustration of being unable to secure genuine film of real battles—or, in the case of the crudest but most charming of the two known solutions produced at the time, get closer to the action than a New York tub. This notoriously inadequate short film was produced by a New York film man named Albert Smith, founder of the prolific American Vitagraph studio in Brooklyn—who, according to his own account, did make it to Cuba, only to find his clumsy cameras were not up to the task of securing usable footage at long distance. He returned to the U.S. with little more than background shots to mull over the problem. Soon afterward came news of a great American naval victory over the outmatched Spanish fleet far away in the Philippines. It was the first time an American squadron had fought a significant battle since the Civil War, and Smith and his partner, James Stuart Blackton, realized that there would be huge demand for footage showing the Spaniards’ destruction. Their solution, Smith wrote in his memoirs, was low-tech but ingenious:

At this time, vendors were selling large sturdy photographs of ships of the American and Spanish fleets. We bought a sheet of each and cut out the battleships. On a table, topside down, we placed one of Blackton’s large canvas-covered frames and filled it with water an inch deep. In order to stand the cutouts of the ships in the water, we nailed them to lengths of wood about an inch square. In this way a little ‘shelf’ was provided behind each ship, and on this ship we placed pinches of gunpowder–three pinches for each ship–not too many, we felt, for a major sea engagement of this sort….

For a background, Blackton daubed a few white clouds on a blue-tinted cardboard. To each of the ships, now sitting placidly in our shallow ‘bay,’ we attached a fine thread to enable us to pull the ships past the camera at the proper moment and in the correct order.

We needed someone to blow smoke into the scene, but we couldn’t go too far outside our circle if the secret was to be kept. Mrs. Blackton was called in and she volunteered, in this day of non-smoking womanhood, to smoke a cigarette. A friendly office boy said he would try a cigar. This was fine, as we needed the volume.

A piece of cotton was dipped in alcohol and attached to a wire slender enough to escape the eye of the camera. Blackton, concealed behind the side of the table farthermost from the camera, touched off the mounds of gunpowder with his wire taper—and the battle was on. Mrs. Blackton, smoking and coughing, delivered a fine haze. Jim had worked out a timing arrangement with her so that she blew the smoke into the scene at approximately the moment of the explosion…

The film lenses of that day were imperfect enough to conceal the crudities of our miniature, and as the picture ran only two minutes there was no time for anyone to study it critically…. Pastor’s and both Proctor houses played to capacity audiences for several weeks. Jim and I felt less remorse of conscience when we saw how much excitement and enthusiasm was aroused by The Battle of Santiago Bay.

Still from Edward H. Amet’s film of the Battle of Matanzas–an unopposed bombardment of a Cuban port in April 1898.

Perhaps surprisingly, Smith’s film (which has apparently been lost) does seem to have fooled the not-terribly-experienced early cinemagoers who viewed it—or perhaps they were simply too polite to mention its obvious shortcomings. Some rather more convincing scenes of a second battle, however, were faked by a rival filmmaker, Edward Hill Amet of Waukegan, Illinois, who—denied permission to travel to Cuba—built a set of detailed, 1:70 scale metal models of the combatants and floated them on a 24-foot-long outdoor tank in his yard in Lake County. Unlike Smith’s hurried effort, Amet’s shoot was meticulously planned, and his models were vastly more realistic; they were carefully based on photographs and plans of the real ships, and each was equipped with working smokestacks and guns containing remotely ignited blasting caps, all controlled from an electrical switchboard. The resulting film, which looks unquestionably amateurish to modern eyes, was nonetheless realistic by the standards of the day, and “according to film-history books,” Margarita De Orellana observes, “the Spanish government bought a copy of Amet’s film for the military archives in Madrid, apparently convinced of its authenticity.”

The Sikander Bagh (Secundra Bagh) in Cawnpore, scene of the massacre of Indian rebels, photographed by Felice Beato

The lesson here, surely, is not that the camera can, and often does, lie, but that it has lied ever since it was invented. “Reconstruction” of battle scenes was born with battlefield photography. Matthew Brady did it during the Civil War. And, even earlier, in 1858, during the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, or rebellion, or war of independence, the pioneer photographer Felice Beato created dramatized reconstructions, and notoriously scattered the skeletal remains of Indians in the foreground of his photograph of the Sikander Bagh in order to enhance the image.

Most interesting of all, perhaps, is the question is how readily those who viewed such pictures accepted them. For the most part, historians have been very ready to assume that the audiences for “faked” photographs and reconstructed movies were notably naive and accepting. A classic instance, still debated, is the reception of the Lumiere Brothers’ pioneering film short Arrival of the Train at the Station, which showed a railway engine pulling into a French terminus, shot by a camera placed on the platform directly in front of it. In the popular retelling of this story, early cinema audiences were so panicked by the fast-approaching train that—unable to distinguish between image and reality—they imagined it would at any second burst through the screen and crash into the cinema. Recent research has, however, more or less comprehensively debunked this story (it has even been suggested that the reception accorded to the original 1896 short has been conflated with panic caused by viewing, in the 1930s, of early 3D movie images)—though, given the lack of sources, it remains highly doubtful precisely what the real reception of the Brothers’ movie was.

Certainly, what impresses the viewer of the first war films today is how ludicrously unreal, and how contrived, they are. According to Bottomore, even the audiences of 1897 gave Georges Méliès’s 1897 fakes a mixed reception:

A few people might have believed that some of the films were genuine, especially if, as sometimes happened, the showmen proclaimed that they were so. Other viewers had doubts on the matter…. Perhaps the best comment on the ambiguous nature of Méliès’ films came from a contemporary journalist who, while describing the films as “wonderfully realistic,” also stated that they were artistically made subjects.

Yet while the brutal truth is surely that Méliès’s shorts were just about as realistic than Amet’s 1:70 ship models, in a sense that hardly matters. These early film-makers were developing techniques that their better-equipped successors would go on to use to shoot real footage of real wars—and stoking demand for shocking combat footage that has fueled many a journalistic triumph. Modern news reporting owes a debt to the pioneers of a century ago—and for as long as it does, the shade of Pancho Villa will ride again.

Sources

John Barnes. Filming the Boer War. Tonbridge: Bishopsgate Press, 1992; Stephen Bottomore. “Frederic Villiers: war correspondent.” In Wheeler W. Dixon (ed), Re-viewing British Cinema, 1900-1992: Essays and Interviews. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994; Stephen Bottomore. Filming, Faking and Propaganda: The Origins of the War Film, 1897-1902. Unpublished University of Utrecht PhD thesis, 2007; James Chapman. War and Film. London: Reaktion Books, 2008; Margarita De Orellana. Filming Pancho: How Hollywood Shaped the Mexican Revolution. London: Verso, 2009; Tom Gunning. “An aesthetic of astonishment: early film and the (in)credulous spectator.” In Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (eds), Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999; Kirk Kekatos. “Edward H. Amet and the Spanish-American War film.” Film History 14 (2002); Martin Loiperdinger. “Lumière’s Arrival of the Train: cinema’s founding myth.” The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists v4n1 (Spring 2004); Albert Smith. Two Reels and a Crank. New York: Doubleday, 1952.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)