The Gadgets of the Future From the Electrical Shows of Yesterday

Decades before the debut of the Consumer Electronics Show, early adopters flocked to extravagant high-tech fairs in New York and Chicago

![]()

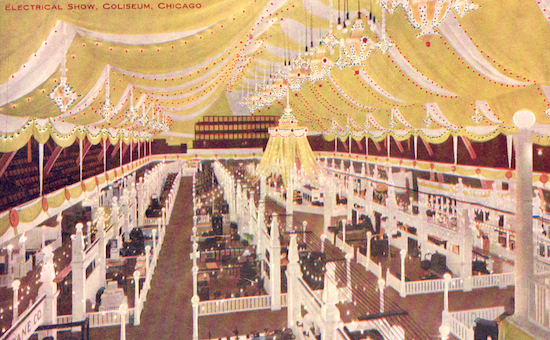

Postcard from the Chicago Electrical Show circa 1908

The Consumer Electronics Show (CES), which concluded last week in Las Vegas, is where the (supposed) future of consumer technology gets displayed. But before this annual show debuted in 1967, where could you go to find the most futuristic gadgets and appliances? The answer was the American electrical shows of 100 years ago.

The first three decades of the 20th century was an incredible period of technological growth for the United States. With the rapid adoption of electricity in the American home, people could power an increasingly large number of strange and glorious gadgets which were being billed as the technological solution for making everyone’s lives easier and more enjoyable. Telephones, vacuum cleaners, electric stoves, motion pictures, radios, x-rays, washing machines, automobiles, airplanes and thousands of other technologies came of age during this time. And there was no better place to see what was coming down the pike than at one of the many electrical shows around the country.

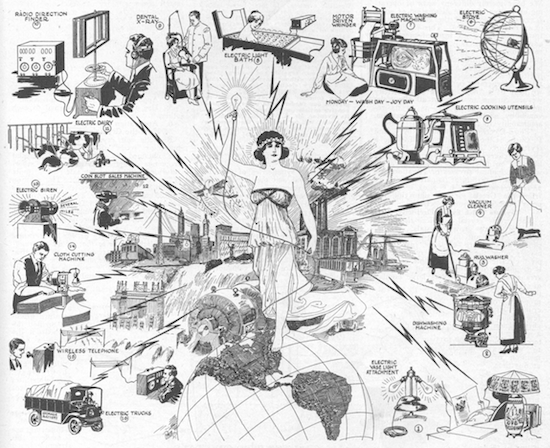

The latest appliances and gadgets from the 1919 New York Electrical Show illustrated in the December 1919 issue of Electrical Experimenter magazine

The two consistently largest electrical shows in the U.S. were in Chicago and New York. Chicago’s annual show opened on January 15, 1906, when less than 8 percent of U.S. households had electricity. By 1929, about 85 percent of American homes (if you exclude farm dwellings) had electricity and the early adopters of the 1920s — emboldened by the rise of consumer credit — couldn’t get their hands on enough appliances.

The first Chicago Electrical Show began with a “wireless message” from President Teddy Roosevelt in the White House and another from Thomas Edison in New Jersey. Over 100,000 people roamed its 30,000 square feet of exhibit space during its two weeks at the Chicago Coliseum.

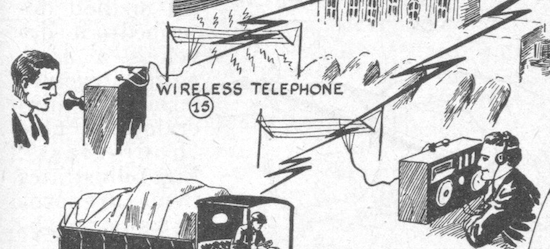

“Wireless telephone” from the 1919 New York Electrical Show

Just as it is today at CES, demonstration was the bread and butter of the early 20th century electrical shows. At the 1907 Chicago Electrical Show the American Vibrator Company gave out complimentary massages to attendees with its electrically driven massagers while the Diehl Manufacturing Company showed off the latest in sewing machine motors for both the home and the factory.

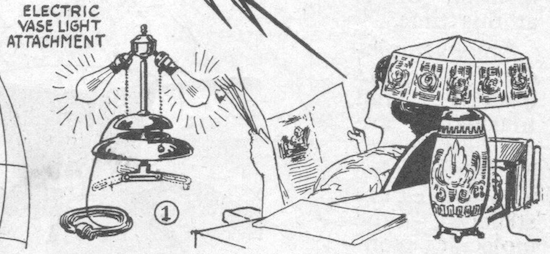

Decorative light was consistently important at all the early electrical shows, as you can see by the many electric lights dangling in the 1908 postcard at the top of this post. The 1909 New York Electrical Show at Madison Square Garden was advertised as being illuminated by 75,000 incandescent lamps and each year the number of light bulbs would grow greater for what the October 5, 1919, Sandusky Register described as “America’s most glittering industry” — electricity.

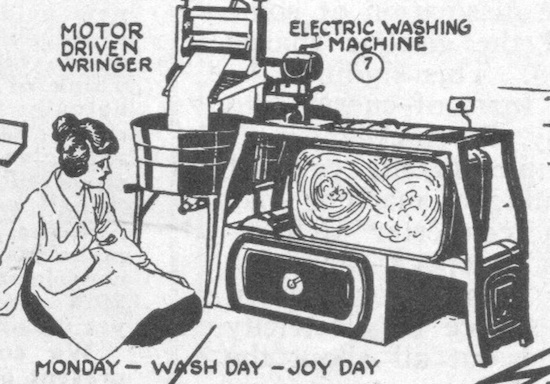

The highlights of the 1909 New York show included “air ships” controlled by wireless, food cooked by electricity, the wireless telephone (technology that today we call radio), washing and ironing by electricity and even hatching chicken eggs by electricity. They also included a demonstration of 2,000,000 volts of electricity sent harmlessly through a man’s body.

The electric washing machine from the 1919 New York Electrical Show

The hot new gadget of the 1910 Chicago show was the “time-a-phone.” This invention looked like a small telephone receiver and allowed a person to tell time in the dark by the number of chimes and gongs they heard. Musical chimes denoted the hour while a set of double gongs gave the quarter hours and a high pitched bell signified the minutes. The January 5, 1910, Iowa City Daily Pressexplained that such an invention could be used in hotels, “where each room will be provided with one of the instruments connected to a master clock in the basement. The time-a-phone is placed under the pillow and any guest wishing to know the hour has to press a button.”

Though the Chicago and New York shows attracted exhibitors from all over the country, they drew largely regional attendees in the 1900s and 1910s. New York’s show of course had visitors from cities in the northeast but it also drew visitors from as far away as Japan who were interested in importing the latest American electrical appliances. Chicago’s show drew from neighboring states like Iowa and Indiana and the show took out ads in the major newspapers in Des Moines and Indianapolis. An ad in the January 10, 1910, Indianapolis Star billed that year’s show in Chicago as the most elaborate exposition ever held — “Chicago’s Billion Dollar Electrical Show.” The ad proclaimed that “everything that’s now in light, heat and power for the home, office, store, factory and farm” would be on display including “all manner of heavy and light machinery in full working operation.”

Dishwashing machine from the 1919 New York Electrical Show

Chicago’s 1910 Electrical Show was advertised as a “Veritable Fairyland of Electrical Wonders” with $40,000 spent on decorations (about $950,000 adjusted for inflation). On display was the The Wright airplane exhibited by the U.S. Government, wireless telegraphy and telephony.

During World War I the nation and most of it’s high-tech (including all radio equipment, which was confiscated from all private citizens by the U.S. government) went to war. Before the war the New York Electrical Show had moved from Madison Square Garden to the Grand Central Palace but during WWI the Palace served as a hospital. New York’s Electrical Show went on hiatus, but in 1919 it returned with much excitement about the promise of things to come.

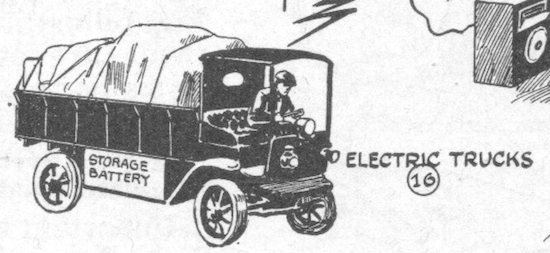

The electric truck on display at the 1919 New York Electrical Show

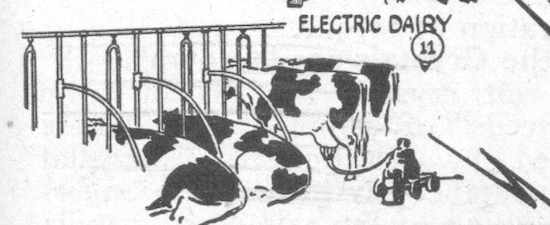

The October 5, 1919, Sandusky Registerin Sandusky, Ohio described the featured exhibits everyone was buzzing about in New York, such as: “a model apartment, an electrical dairy, electrical bakery, therapeutic display, motion picture theater, the dental college tube X ray unit, the magnifying radioscope, a domestic ice making refrigerating unit, a carpet washer which not only cleans but restores colors and kills germs.”

Model homes and apartments were both popular staples of the early 20th century electrical shows. Naturally, the Chicago show regularly featured a house of the future, while the New York show typically called their model home an apartment. Either way, both were extravagantly futuristic places where nearly everything seemed to be aided by electricity.

The model apartment at the 1919 New York Electrical Show included a small electric grand piano with decorative electric candles. A tea table with an electric hot water kettle, a lunch table with chafing dishes and and electric percolator. The apartment of tomorrow even came with a fully equipped kitchen with an electric range and an electric refrigerator. Daily demonstrations showed off how electricity could help in the baking of cakes and pastry, preparing dinner, as well as in canning and preserving. The hottest gadgets of the 1919 NY show included the latest improvements in radio, dishwashing machines and a ridiculous number of vacuum cleaners. The December 1919 issue of Electrical Experimenter magazine described the editors as “flabbergasted” trying to count the total number of vacuum cleaners being demonstrated.

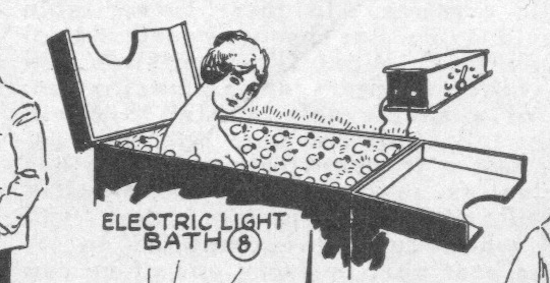

The “electric light bath” at the 1919 New York Electrical Show

After WWI the electrical shows really kicked into high gear, and not just in New York and Chicago. Cleveland advertised its electrical show in 1920 as the biggest ever staged in America. Held in the Bolivar-Ninth building the show was decidedly more farm-centric, with the latest in electrical cleaners for cows getting top billing in Ohio newspapers. The Cleveland show included everything from cream separators that operate while the farmer is out doing other chores to milking machines to industrial sized refrigerators for keeping perishable farm products fresh.

The “electric dairy” from the 1919 New York Electrical Show

The 1921 New York Electrical Show featured over ninety booths with over 450 different appliances on display. Americans of the early 1920s were promised that in the future the human body would be cared for by electricity from head to toe. The electric toothbrush was one of the most talked about displays. The American of the future would be bathing in electrically-heated water, and afterward put on clothes that had been electrically sewn, electrically cleaned and electrically pressed. The electrical shows of the early 20th century promised that the American of the future would only be eating meals that were prepared electrically. What was described by some as the most interesting exhibit of the 1921 New York Electrical Show, the light that stays on for a full minute after you turn it off. This, it was explained, gave you time to reach your bed or wherever you’re heading without “hitting your toes against the rocking chair” and waking up the rest of your family.

The “electric vase light attachment” from the 1919 New York Electrical Show

The Great Depression would stall that era’s American electrical shows. In 1930 the New York Electrical Show didn’t happen and Earl Whitehorne, president of the Electrical Association of New York, made the announcement. The Radio Manufacturers Association really took up the mantle, holding events in Chicago, New York and Atlantic City where previous exhibitors at the Electrical Shows were encouraged to demonstrate their wares. But it wasn’t quite the same. The sale of mechanical refrigerators, radios and even automobiles would continue in the 1930s, but the easy credit and sky’s-the-limit dreaming of the electrically minded would be relegated to certain corners of larger American fairs (like the World’s Fairs of 1933 in Chicago and 1939 in New York) where techno-utopian dreams were largely the domain of gigantic corporations like RCA and Westinghouse.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)