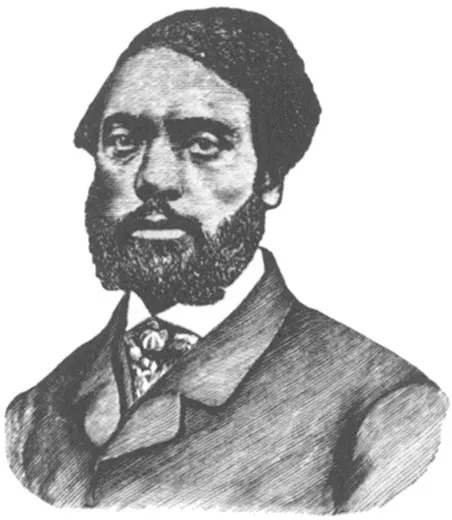

The Great Escape From Slavery of Ellen and William Craft

Passing as a white man traveling with his servant, two slaves fled their masters in a thrilling tale of deception and intrigue

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ellen-Craft-and-William-Craft-631.jpg)

Most runaway slaves fled to freedom in the dead of night, often pursued by barking bloodhounds. A few fugitives, such as Henry “Box” Brown who mailed himself north in a wooden crate, devised clever ruses or stowed away on ships and wagons. One of the most ingenious escapes was that of a married couple from Georgia, Ellen and William Craft, who traveled in first-class trains, dined with a steamboat captain and stayed in the best hotels during their escape to Philadelphia and freedom in 1848. Ellen, a quadroon with very fair skin, disguised herself as a young white cotton planter traveling with his slave (William). It was William who came up with the scheme to hide in plain sight, but ultimately it was Ellen who convincingly masked her race, her gender and her social status during their four-day trip. Despite the luxury accommodations, the journey was fraught with narrow escapes and heart-in-the-mouth moments that could have led to their discovery and capture. Courage, quick thinking, luck and “our Heavenly Father,” sustained them, the Crafts said in Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, the book they wrote in 1860 chronicling the escape.

Ellen and William lived in Macon, Georgia, and were owned by different masters. Put up for auction at age 16 to help settle his master’s debts, William had become the property of a local bank cashier. A skilled cabinetmaker, William, continued to work at the shop where he had apprenticed, and his new owner collected most of his wages. Minutes before being sold, William had witnessed the sale of his frightened, tearful 14-year-old sister. His parents and brother had met the same fate and were scattered throughout the South.

As a child, Ellen, the offspring of her first master and one of his biracial slaves, had frequently been mistaken for a member of his white family. Much annoyed by the situation, the plantation mistress sent 11-year-old Ellen to Macon to her daughter as a wedding present in 1837, where she served as a ladies maid. Ellen and William married, but having experienced such brutal family separations despaired over having children, fearing they would be torn away from them. “The mere thought,” William later wrote of his wife’s distress, “filled her soul with horror.”

Pondering various escape plans, William, knowing that slaveholders could take their slaves to any state, slave or free, hit upon the idea of fair-complexioned Ellen passing herself off as his master—a wealthy young white man because it was not customary for women to travel with male servants. Initially Ellen panicked at the idea but was gradually won over. Because they were “favourite slaves,” the couple had little trouble obtaining passes from their masters for a few days leave at Christmastime, giving them some days to be missing without raising the alarm. Additionally, as a carpenter, William probably would have kept some of his earnings – or perhaps did odd jobs for others – and was allowed to keep some of the money.

Before setting out on December 21, 1848, William cut Ellen’s hair to neck length. She improved on the deception by putting her right arm in a sling, which would prevent hotel clerks and others from expecting “him” to sign a registry or other papers. Georgia law prohibited teaching slaves to read or write, so neither Ellen nor William could do either. Refining the invalid disguise, Ellen asked William to wrap bandages around much of her face, hiding her smooth skin and giving her a reason to limit conversation with strangers. She wore a pair of men’s trousers that she herself had sewed. She then donned a pair of green spectacles and a top hat. They knelt and prayed and took “a desperate leap for liberty.”

At the Macon train station, Ellen purchased tickets to Savannah, 200 miles away. As William took a place in the “negro car,” he spotted the owner of the cabinetmaking shop on the platform. After questioning the ticket seller, the man began peering through the windows of the cars. William turned his face from the window and shrank in his seat, expecting the worst. The man searched the car Ellen was in but never gave the bandaged invalid a second glance. Just as he approached William’s car, the bell clanged and the train lurched off.

Ellen, who had been staring out the window, then turned away and discovered that her seat mate was a dear friend of her master, a recent dinner guest who had known Ellen for years. Her first thought was that he had been sent to retrieve her, but the wave of fear soon passed when he greeted her with “It is a very fine morning, sir.”

To avoid talking to him, Ellen feigned deafness for the next several hours.

In Savannah, the fugitives boarded a steamer for Charleston, South Carolina. Over breakfast the next morning, the friendly captain marveled at the young master’s “very attentive boy” and warned him to beware “cut-throat abolitionists” in the North who would encourage William to run away. A slave trader on board offered to buy William and take him to the Deep South, and a military officer scolded the invalid for saying “thank you” to his slave. In an overnight stay at the best hotel in Charleston, the solicitous staff treated the ailing traveler with upmost care, giving him a fine room and a good table in the dining room.

Trying to buy steamer tickets from South Carolina to Philadelphia, Ellen and William hit a snag when the ticket seller objected to signing the names of the young gentleman and his slave even after seeing the injured arm. In an effort to prevent white abolitionists from taking slaves out of the South, slaveholders had to prove that the slaves traveling with them were indeed their property. Sometimes travelers were detained for days trying to prove ownership. As the surly ticket seller reiterated his refusal to sign by jamming his hands in his pockets, providence prevailed: The genial captain happened by, vouched for the planter and his slave and signed their names.

Baltimore, the last major stop before Pennsylvania, a free state, had a particularly vigilant border patrol. Ellen and William were again detained, asked to leave the train and report to the authorities for verification of ownership. “We shan’t let you go,” an officer said with finality. “We felt as though we had come into deep waters and were about being overwhelmed,” William recounted in the book, and returned “to the dark and horrible pit of misery.” Ellen and William silently prayed as the officer stood his ground. Suddenly the jangling of the departure bell shattered the quiet. The officer, clearly agitated, scratched his head. Surveying the sick traveler’s bandages, he said to a clerk, “he is not well, it is a pity to stop him.” Tell the conductor to “let this gentleman and slave pass.”

The Crafts arrived in Philadelphia the next morning—Christmas Day. As they left the station, Ellen burst into tears, crying out, “Thank God, William, we’re safe!”

The comfortable coaches and cabins notwithstanding, it had been an emotionally harrowing journey, especially for Ellen as she kept up the multilayered deception. From making excuses for not partaking of brandy and cigars with the other gentleman to worrying that slavers had kidnapped William, her nerves were frayed to the point of exhaustion. At a Virginia railway station, a woman had even mistaken William for her runaway slave and demanded that he come with her. As predicted, abolitionists approached William. One advised him to “leave that cripple and have your liberty,” and a free black man on the train to Philadelphia urged him to take refuge in a boarding house run by abolitionists. Through it all Ellen and William maintained their roles, never revealing anything of themselves to the strangers except a loyal slave and kind master.

Upon their arrival in Philadelphia, Ellen and William were quickly given assistance and lodging by the underground abolitionist network. They received a reading lesson their very first day in the city. Three weeks later, they moved to Boston where William resumed work as a cabinetmaker and Ellen became a seamstress. After two years, in 1850, slave hunters arrived in Boston intent on returning them to Georgia. The Crafts fled again, this time to England, where they eventually had five children. After 20 years they returned to the States and in the 1870s established a school in Georgia for newly freed blacks.