The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance

![]()

Mugshots as Lydia DeVere (left) and Cassie Chadwick. Credit: Cleveland Police Museum

In the spring of 1902 a woman calling herself Cassie L. Chadwick—there was never any mention as to what the L stood for—took a train from Cleveland to New York City and a hansom cab to the Holland House, a hotel at the corner of 30th Street and Fifth Avenue internationally renowned for its gilded banquet room and $350,000 wine cellar. She waited in the lobby, tapping her high-button shoes on the Sienna marble floor, watching men glide by in their bowler hats and frock coats, searching for one man in particular. There he was—James Dillon, a lawyer and friend of her husband’s, standing alone.

She walked toward him, grazing his arm as she passed, and waited for him to pardon himself. As he said the words she spun around and exclaimed what a delightful coincidence it was to see him here, so far from home. She was in town briefly on some private business. In fact, she was on her way to her father’s house—would Mr. Dillon be so kind as to escort her there?

Dillon, happy to oblige, hailed an open carriage. Cassie gave the driver an address: 2 East 91st Street, at Fifth Avenue, and kept up a cheery patter until they arrived there—at a four-story mansion belonging to steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. She tried not to laugh at Dillon’s sudden inability to speak and told him she’d be back shortly. The butler opened the door to find a refined, well-dressed lady who politely asked to speak to the head housekeeper.

When the woman presented herself, Cassie explained that she was thinking of hiring a maid, Hilda Schmidt, who had supposedly worked for the Carnegie family. She wished to check the woman’s references. The housekeeper was puzzled, and said no one by that name had ever worked for the Carnegie family. Cassie protested: Was she absolutely certain? She gave a detailed physical description, rattled off details of the woman’s background. No, the housekeeper insisted; there must be some misunderstanding. Cassie thanked her profusely, complimented the spotlessness of the front parlor, and let herself out, slipping a large brown envelope out of her coat as she turned back to the street. She had managed to stretch the encounter into just under a half hour.

As she climbed into the carriage, Dillon apologized for what he was about to ask: Who was her father, exactly? Please, Cassie said, raising a gloved finger to her lips, he mustn’t disclose her secret to anyone: She was Andrew Carnegie’s illegitimate daughter. She handed over the envelope, which contained a pair of promissory notes, for $250,000 and $500,000, signed by Carnegie himself, and securities valued at a total of $5 million. Out of guilt and a sense of responsibility, “Daddy” gave her large sums of money, she said; she had numerous other notes stashed in a dresser drawer at home. Furthermore, she stood to inherit millions when he died. She reminded Dillon not to speak of her parentage, knowing it was a promise he wouldn’t keep; the story was too fantastic to withhold, and too brazen to be untrue. But she had never met Andrew Carnegie. Cassie Chadwick was just one of many names she went by.

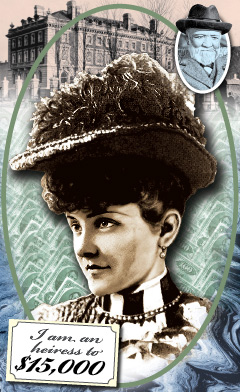

“Betty” Bigley’s calling card, courtesy of the New York Daily News

Elizabeth “Betty” Bigley was born in October 1857, the fifth of eight children, and grew up on a small farm in Ontario, Canada. As a girl Betty lost her hearing in one ear and developed a speech impediment, which conditioned her to speak few words and choose them with care. Her classmates found her “peculiar” and she turned inward, sitting in silence by the hour. One sister, Alice, said Betty often seemed to be in a trance, as if she had hypnotized herself, unable to see or hear anything that existed outside of her mind. Coming out of these spells, she seemed disoriented and bewildered but refused to discuss her thoughts. Sometimes, Alice noticed her practicing family members’ signatures, scrawling the names over and over again.

At the age of 13 Betty devised her first scheme, writing a letter saying an uncle had died and left her a small sum of money. This forged notification of inheritance looked authentic enough to dupe a local bank, which issued checks allowing her to spend the money in advance. The checks were genuine, but the accounts nonexistent. After a few months she was arrested and warned to never do it again.

Instead, in 1879, at the age of 22, Betty launched what would become her trademark scam. She saved up for expensive letterhead and, using the fictitious name and address of a London, Ontario, attorney, notified herself that a philanthropist had died and left her an inheritance of $15,000. Next, she needed to announce her good fortune, presenting herself in a manner that would allow her to spend her “inheritance.” To this end, she had a printer create business cards resembling the calling cards of the social elite. Hers read: “Miss Bigley, Heiress to $15,000.”

She came up with a simple plan that capitalized on the lackadaisical business practices of the day. She would enter a shop, choose an expensive item, and then write a check for a sum that exceeded its price. Many merchants were willing to give her the cash difference between the cost of the item and the amount of the check. If anyone questioned whether she could afford her purchases, she coolly produced her calling card. It worked every time. Why would a young woman have a card announcing she was an heiress if it weren’t true?

Betty then headed to Cleveland to live with her sister Alice, who was now married. She promised Alice she didn’t want to impose on the newlyweds, and would stay only as long as it took to launch herself. While Alice thought her sister was seeking a job at a factory or shop, Betty was roaming the house, taking stock of everything from chairs to cutlery to paintings. She estimated their value and then arranged for a bank loan, using the furnishings as collateral. When Alice’s husband discovered the ruse he kicked Betty out, and she moved to another neighborhood in the city, where she met one Dr. Wallace S. Springsteen.

The doctor was immediately captivated. Although Betty was rather plain, with a tight, unsmiling mouth and a nest of dull brown hair, her eyes had a singular intensity—one newspaper would dub her “the Lady of the Hypnotic Eye”—and the gentle lisp of her voice seemed to impart a quiet truth to her every word. She and the doctor married before a justice of the peace in December 1883, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer printed a notice of their union. Within days a number of furious merchants showed up at the couple’s home demanding to be repaid. Dr. Springsteen checked their stories and begrudgingly paid off his wife’s debts, fearing that his own credit was on the line. The marriage lasted 12 days.

The time had come to reinvent herself, and Betty became Mme. Marie Rosa and lived in various boardinghouses, scamming merchants and honing her skills. Traveling through Erie, Pennsylvania, she impressed the locals by claiming to be the niece of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman and then pretended to be very ill; one witness reported that “through a trick of extracting blood from her gums she led persons to believe she was suffering from a hemorrhage.” The kind people of Erie turned out their pockets to collect enough money to send her back to Cleveland. When they wrote to her for repayment of those loans, they received letters in reply saying that poor Marie had died two weeks ago. As a finishing touch, Betty included a tender tribute to the deceased that she’d written herself.

As Mme. Rosa, Betty claimed to be a clairvoyant and married two of her clients. The first was a short-lived union with a Trumbull County farmer; the second was to businessman C.L. Hoover, with whom she had a son, Emil. (The boy was sent to be raised by her parents and siblings in Canada.) Hoover died in 1888, leaving Betty an estate worth $50,000. She moved to Toledo and assumed a new identity, living as Mme. Lydia Devere and continuing her work as a clairvoyant. A client named Joseph Lamb paid her $10,000 to serve as his financial adviser and seemed willing to do any favor she asked. He, along with numerous other victims, would later claim that she had hypnotic powers, a popular concept at the turn of the 20thcentury. Some 8 million people believed that spirits could be conjured from the dead and that hypnotism was an acceptable explanation for adultery, runaway teenagers and the increasingly common occurrence of young shopgirls fleeing with strange men they met on trains.

Lydia prepared a promissory note for several thousand dollars, forged the signature of a prominent Clevelander, and told Lamb to cash it for her at his bank in Toledo. If he refused, she explained, she would have to travel across the state to get her money. He had an excellent reputation in Toledo, cashed the check without incident, and, at Betty’s request, cashed several more totaling $40,000. When the banks caught on, both Betty and Joseph were arrested. Joseph was perceived as her victim and acquitted of all charges. Betty was convicted of forgery and sentenced to nine and a half years in the state penitentiary. Even there she posed as a clairvoyant, telling the warden that he would lose $5,000 in a business deal (which he did) and then die of cancer (which he also did). From her jail cell she began a letter-writing campaign to the parole board, proclaiming her remorse and promising to change. Three and a half years into her sentence, Governor (and future President) William McKinley signed the papers for her release.

She returned to Cleveland as Cassie L. Hoover and married another doctor, Leroy S. Chadwick, a wealthy widower and descendent of one of Cleveland’s oldest families. She sent for her son and moved with him into the doctor’s palatial residence on Euclid Avenue, the most aristocratic thoroughfare in the city. The marriage was a surprise to Chadwick’s friends; none of them had heard of Cassie until he introduced her as his wife. Her history and family were unknown. There were whispers that she had run a brothel and that the lonely doctor had been one of her clients. He divulged only that he had been suffering from rheumatism in his back, which Cassie generously relieved with an impromptu massage, and he couldn’t help but fall in love with her “compassion.”

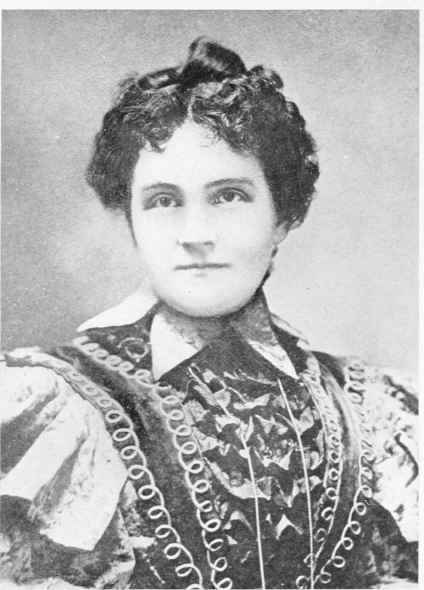

Cassie Chadwick, 1904. Credit: Cleveland State University

The new Cassie L. Chadwick was eager to impress her prominent neighbors, among them relations of John D. Rockefeller, U.S. Senator Marcus Hanna and John Hay, who had been one of Abraham Lincoln’s private secretaries. She bought everything that struck her fancy and never asked the price. She replaced the doctor’s musty drapes and gloomy oil portraits with bright, whimsical pieces: a perpetual-motion clock encased in glass; a $9,000 pipe organ; a “musical chair” that plunked out a tune when someone sat down. She had a chest containing eight trays of diamonds and pearls, inventoried at $98,000, and a $40,000 rope of pearls. She ordered custom-made hats and clothing from New York, sculptures from the Far East, and furniture from Europe. During the Christmas season in 1903, the year after James Dillon told all of Cleveland about her shocking connection to Andrew Carnegie, she bought eight pianos at a time and presented them as gifts to friends. Even when purchasing the smallest toiletries she insisted on paying top dollar. “If a thing didn’t cost enough to suit her,” one acquaintance reported, “she would order it thrown away.” When her husband began objecting to her profligacy, she borrowed against her future inheritance. Her financial associates never believed that Mrs. Chadwick would be capable of creating an elaborate paper trail of lies.

Her scam involved large sums of money from financial institutions—Ohio Citizen’s Bank, Cleveland’s Wade Park Banking Company, New York’s Lincoln National Bank—and smaller sums, though never less than $10,000, from as many as a dozen other banks. She would take out several loans, repaying the first with money from the second, repaying the second with money from the third, and so on. She chose Wade Park Bank as her base of operations, entrusting it with her counterfeit promissory notes from Carnegie. She convinced Charles Beckwith, the president of Citizen’s National Bank, to grant her a loan of $240,000, plus an additional $100,000 from his personal account. A Pittsburgh steel mogul, likely an acquaintance of Carnegie’s, gave her $800,000. Through the prestigious Euclid Avenue Baptist Church, Cassie connected with Herbert Newton, an investment banker in Boston. He was thrilled to provide her with a loan and wrote her a check from his business for $79,000 and a personal check for $25,000—$104,000. He was even more pleased when she signed a promissory note for $190,800 without questioning the outrageous interest.

By November 1904, Newton realized that Cassie had no intention of repaying the loans, let alone any interest, and filed suit in federal court in Cleveland. In order to prevent her from moving and hiding her money, the suit requested that Ira Reynolds, secretary and treasurer of Wade Park Banking Company of Cleveland (who himself had lent most of his personal fortune to Cassie), continue to hold the promissory notes from her “father.”

Cassie denied all charges, and also the claim of any relationship with Andrew Carnegie. “It has been said repeatedly that I had asserted that Andrew Carnegie was my father,” she said. “I deny that, and I deny it absolutely.” Charles Beckwith, the bank president, visited her in jail. Although Cassie’s frauds had caused his bank to collapse and decimated his personal wealth, he studied her skeptically through the bars of her cell. “You’ve ruined me,” he said, “but I’m not so sure yet you are a fraud.” To this day the full extent of Cassie’s spoils remains unknown—some historians believe that many victims declined to come forward—but the most commonly cited sum is $633,000, about $16.5 million in today’s dollars.

In March 1905, Cassie Chadwick was found guilty of conspiracy to defraud a national bank and sentenced to 10 years in the penitentiary. Carnegie himself attended the trial, and later had the chance to examine the infamous promissory notes. “If anybody had seen this paper and then really believed that I had drawn it up and signed it, I could hardly have been flattered,” he said, pointing out errors in spelling and punctuation. “Why, I have not signed a note in the last 30 years.” The whole scandal could have been avoided, he added, if anyone had bothered to ask him.

Sources:

Books: John S. Crosbie, The Incredible Mrs. Chadwick. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975. Kerry Segrave, Women Swindlers in America, 1860-1920. New York: McFarland & Company, 2007; Carlson Wade, Great Hoaxes and Famous Impostors. Middle Village, New York: Jonathan Davis Publishers, 1976; Ted Schwarz, Cleveland Curiosities. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010.

Articles: “Mrs. Chadwick: The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance.” Washington Post, December 25, 1904; “The Mystery of Cassie L. Chadwick.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 18, 1904; “Cassie For $800,000.” Washington Post, November 5, 1907; “Carnegie On Chadwick Case.” New York Times, December 29, 1904; “Queen of Swindlers.” Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1936; “Carnegie Sees Note.” New York Times, March 6, 1905; “Got Millions on Carnegie’s Name.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 11, 1904; “Woman Juggles With Millions.” The National Police Gazette, December 31, 1904; “The Career of Cassie.” Los Angeles Times, December 20, 1904; “Carnegie Not My Father; I Never Said That He Was.” Atlanta Constitution, March 25, 1905; “The Case of Mrs. Chadwick.” Congregationalist and Christian World, December 17, 1904.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)