The History of the Teddy Bear: From Wet and Angry to Soft and Cuddly

After Teddy Roosevelt’s act of sportsmanship in 1902 was made legendary by a political cartoonist, his name was forever affixed to an American classic

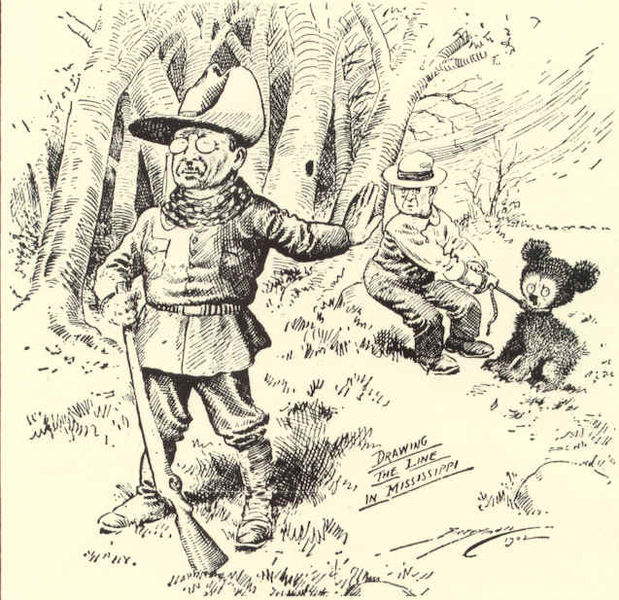

This 1902 cartoon in the Washington Post was the inspiration behind the birth of the “teddy bear.” Photo: Wikipedia

Boxed and wrapped in paper and bows, teddy bears have been placed lovingly underneath Christmas trees for generations, to the delight of tots and toddlers around the world. But the teddy bear is an American original: Its story begins with a holiday vacation taken by President Theodore Roosevelt.

By the spring of 1902, the United Mine Workers of America were on strike, seeking shorter workdays and higher wages from a coal industry that was suffering from oversupply and low profits. The mine owners had welcomed the strike because they could not legally shut down production; it gave them a way to save on wages while driving up demand and prices.

Neither side was willing to give in, and fearing a deadly wintertime shortage of coal, Roosevelt decided to intervene, threatening to send in troops to the Midwest to take over the anthracite mines if the two sides couldn’t come to an agreement. Throughout the fall, despite the risk of a major political setback, Roosevelt met with union representatives and coal operators. In late October, as temperatures began to drop, the union and the owners struck a deal.

After averting that disaster, Roosevelt decided he needed a vacation, so he accepted an invitation from Mississippi Governor Andrew Longino to head south for a hunting trip. Longino was the first Mississippi governor elected after the Civil War who was not a Confederate veteran, and he would soon be facing a re-election fight against James Vardaman, who declared, “If it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy.” Longino was clearly hoping that a visit from the popular president might help him stave off a growing wave of such sentiment. Vardaman called Roosevelt the “coon-flavored miscegenist in the White House.”

Undeterred, Roosevelt met Longino in mid-November, 1902, and the two traveled to the town of Onward, 30 miles north of Vicksburg. In the lowlands they set up camp with trappers, horses, tents, supplies, 50 hunting dogs, journalists and a former slave named Holt Collier as their guide.

As a cavalryman for Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest during the Civil War, Collier knew the land well. He had also killed more than 3,000 bears over his lifetime. Longino enlisted his expertise because hunting for bear in the swamps was dangerous (which Roosevelt relished). “He was safer with me than with all the policemen in Washington,” Collier later said.

The hunt had been scheduled as a 10-day excursion, but Roosevelt was impatient. “I must see a live bear the first day,” he told Collier. He didn’t. But the next morning, Collier’s hounds picked up the scent of a bear, and the president spent the next several hours in pursuit, tracking through mud and thicket. After a break for lunch, Collier’s dogs had chased an old, fat, 235-pound black bear into a watering hole. Cornered by the barking hounds, the bear swiped several with its paws, then crushed one to death. Collier bugled for Roosevelt to join the hunt, then approached the bear. Wanting to save the kill for the president but seeing that his dogs were in danger, Collier swung his rifle and smashed the bear in the skull. He then tied it to a nearby tree and waited for Roosevelt.

When the president caught up with Collier, he came upon a horrific scene: a bloody, gasping bear tied to a tree, dead and injured dogs, a crowd of hunters shouting, “Let the president shoot the bear!” As Roosevelt entered the water, Collier told him, “Don’t shoot him while he’s tied.” But he refused to draw his gun, believing such a kill would be unsportsmanlike.

Collier then approached the bear with another hunter and, after a terrible struggle in the water, killed it with his knife. The animal was slung over a horse and taken back to camp.

News of Roosevelt’s compassionate gesture soon spread throughout the country, and by Monday morning, November 17, cartoonist Clifford K. Berryman’s sketch appeared in the pages of the Washington Post. In it, Roosevelt is dressed in full rough rider uniform, with his back to a corralled, frightened and very docile bear cub, refusing to shoot. The cartoon was titled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi,” believed to be a double-entendre of Roosevelt’s sportsman’s code and his criticism of lynchings in the South. The drawing became so popular that Berryman drew even smaller and cuter “teddy bears” in political cartoons for the rest of Roosevelt’s days as president.

Back in Brooklyn, N.Y., Morris and Rose Michtom, a married Russian Jewish immigrant couple who had a penny store that sold candy and other items, followed the news of the president’s hunting trip. That night, Rose quickly formed a piece of plush velvet into the shape of a bear, sewed on some eyes, and the next morning, the Michtoms had “Teddy’s bear” displayed in their store window.

One of the original teddy bears, donated by the Michtom family and on display at National Museum of American History. Photo: Smithsonian

That day, more than a dozen people asked if they could buy the bear. Thinking they might need permission from the White House to produce the stuffed animals, the Michtoms mailed the original to the president as a gift for his children and asked if he’d mind if they used his name on the bear. Roosevelt, doubting it would make a difference, consented.

Teddy’s bear became so popular the Michtoms left the candy business and devoted themselves to the manufacture of stuffed bears. Roosevelt adopted the teddy bear as the symbol of the Republican Party for the 1904 election, and the Michtoms would ultimately make a fortune as proprietors of the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company. In 1963, they donated one of the first teddy bears to the Smithsonian Institution. It’s currently on view in the American Presidency gallery at the National Museum of American History.

Sources

Articles: ”Holt Collier, Mississippi” Published in George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography. Westport, Connecticut: The Greenwood Press, Inc.,1979, Supplement Series1, v.7, p. 447-478. American Slave Narratives, Collected by the Federal Writers Project, Works Progress Administration, http://newdeal.feri.org/asn/asn03.htm ”The Great Bear Hunt,” by Douglas Brinkley, National Geographic, May 5, 2001. “James K. Vardaman,” Fatal Flood, American Experience, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/flood-vardaman/ ”Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902,” by Rachael Marks, University of St. Francis, http://www.stfrancis.edu/content/ba/ghkickul/stuwebs/btopics/works/anthracitestrike.htm “The Story of the Teddy Bear,” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/thrb/historyculture/storyofteddybear.htm “Rose and Morris Michtom and the Invention of the Teddy Bear,” Jewish Virtual Library, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Michtoms.html “Origins of the Teddy Bear,” by Elizabeth Berlin Taylor, The Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History, http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/politics-reform/resources/origins-teddy-bear “Teddy Bear,” Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University, http://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Learn-About-TR/Themes/Culture-and-Society/Teddy-Bear.aspx

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)