The Kentucky Derby’s Forgotten Jockeys

African American jockeys once dominated the track. But by 1921, they had disappeared from the Kentucky Derby

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/James-Winkfield-riding-Alan-A-Dale-1902-631.jpg)

When tens of thousands of fans assemble in Louisville, Kentucky, for the Kentucky Derby, they will witness a phenomenon somewhat unusual for today’s American sporting events: of some 20 riders, none are African-American. Yet in the first Kentucky Derby in 1875, 13 out of 15 jockeys were black. Among the first 28 derby winners, 15 were black. African-American jockeys excelled in the sport in the late 1800s. But by 1921, they had disappeared from the Kentucky track and would not return until Marlon St. Julien rode in the 2000 race.

African-American jockeys’ dominance in the world of racing is a history nearly forgotten today. Their participation dates back to colonial times, when the British brought their love of horseracing to the New World. Founding Fathers George Washington and Thomas Jefferson frequented the track, and when President Andrew Jackson moved into the White House in 1829, he brought along his best Thoroughbreds and his black jockeys. Because racing was tremendously popular in the South, it is not surprising that the first black jockeys were slaves. They cleaned the stables and handled the grooming and training of some of the country’s most valuable horseflesh. From such responsibility, slaves developed the abilities needed to calm and connect with Thoroughbreds, skills demanded of successful jockeys.

For blacks, racing provided a false sense of freedom. They were allowed to travel the racing circuit, and some even managed their owners’ racing operation. They competed alongside whites. When black riders were cheered to the finish line, the only colors that mattered were the colors of their silk jackets, representing their stables. Horseracing was entertaining for white owners and slaves alike and one of the few ways for slaves to achieve status.

After the Civil War, which had devastated racing in the South, emancipated African-American jockeys followed the money to tracks in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. “African Americans had been involved in racing and with horses since the beginning,” says Anne Butler, director of Kentucky State University's Center for the Study of Kentucky African Americans. “By the time freedom came they were still rooted in the sport.”

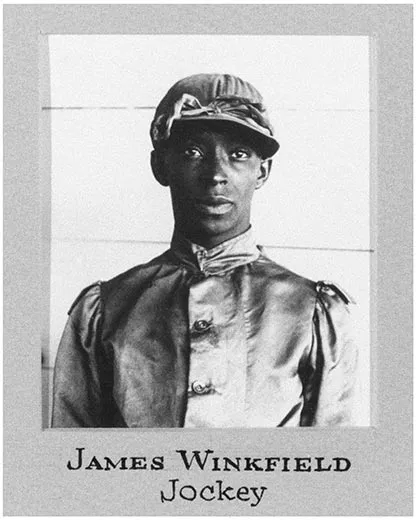

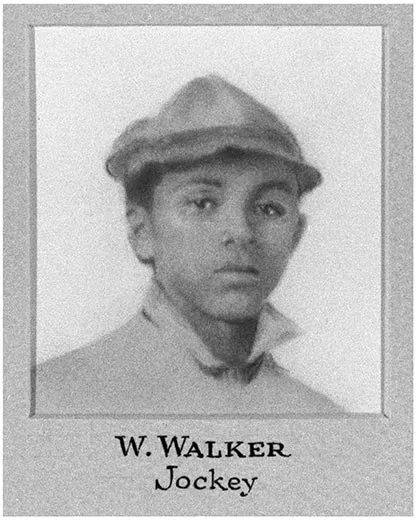

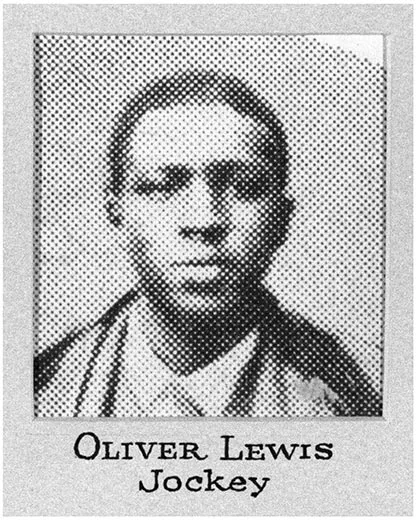

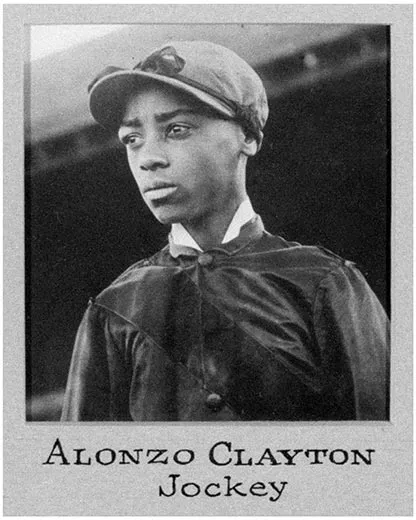

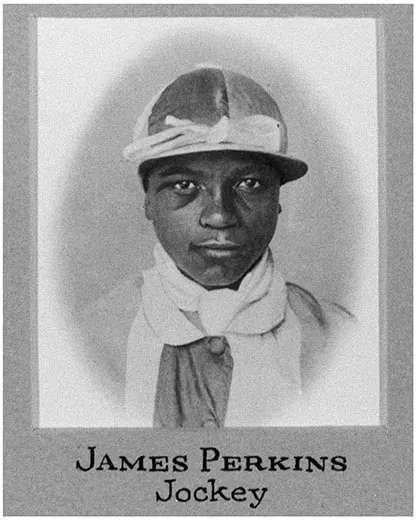

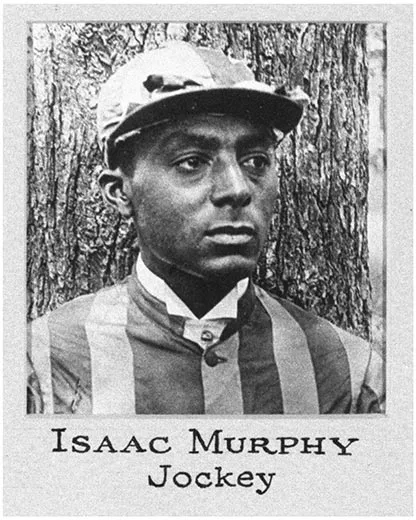

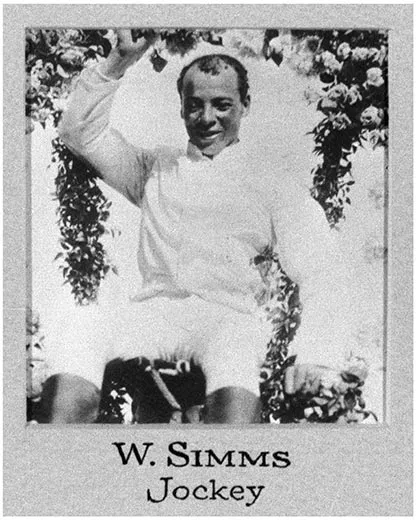

The freed riders soon took center stage at the newly organized Kentucky Derby. On opening day, May 17, 1875, Oliver Lewis, a 19-year-old black native Kentuckian, rode Aristides, a chestnut colt trained by a former slave, to a record-setting victory. Two years later William Walker, 17, claimed the race. Isaac Murphy became the first jockey to win three Kentucky Derbys, in 1884, 1890, and 1891, and won an amazing 44 percent of all the races he rode, a record still unmatched. Alonzo "Lonnie" Clayton, at 15 the youngest to win in 1892, was followed by James "Soup" Perkins, who began racing at age 11 and claimed the 1895 Derby. Willie Simms won in 1896 and 1898. Jimmy "Wink" Winkfield, victorious in 1901 and 1902, would be the last African American to win the world-famous race. Murphy, Simms and Winkfield have been inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, New York.

In 2005, Winkfield was also honored with a Congressional House Resolution, a few days before the 131st Derby. Such accolades came long after his death in 1974 at age 91 and decades after racism forced him and other black jockeys off American racetracks.

Despite Wink’s winning more than 160 races in 1901, Goodwin's Annual Official Guide to the Turf omitted his name. The rising scourge of segregation began seeping into horse racing in the late 1890s. Fanned by the Supreme Court's 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that upheld the "separate but equal" doctrine, Jim Crow injustice pervaded every social arena, says Butler.

“White genteel class, remnants from that world, didn't want to share the bleachers with African American spectators, though blacks continued to work as groomers and trainers," she says.

Racism, coupled with the economic recessions of the period, shrunk the demand for black jockeys as racetracks closed and attendance fell. With intensified competition for mounts, violence on the tracks against black jockeys by white jockeys prevailed without recourse. Winkfield received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Anti-gambling groups campaigned against racing, causing more closures and the northern migration of blacks from southern farming communities further contributed to the decline of black jockeys.

Winkfield dealt another serious blow to his career by jumping a contract. With fewer and fewer mounts coming his way, he left the United States in 1904 for Czarist Russia, where his riding skills earned him celebrity and fortune beyond his dreams. Fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, he moved to France, raced for another decade and retired in 1930 after a career 2,600 wins. In 1940, Nazis seized his stables, causing Winkfield to return to States, where he signed on to a Works Progress Administration road crew. Back in France by 1953, he opened a training school for jockeys. In 1961, six decades after winning his first Kentucky Derby, Winkfield returned to Kentucky to attend a pre-Derby banquet. When he and his daughter Liliane arrived at Louisville's historic Brown Hotel, they were denied entry. After a long wait and repeated explanations that they were guests of Sports Illustrated, they were finally admitted. Wink died 13 years later in France.

After his 1903 run in the Kentucky Derby, black Americans practically disappeared from Goodwin’s official list of jockeys. In 1911 Jess Conley came in third in the derby and in 1921, Henry King placed tenth. Seventy-nine years would pass before another African American would ride in the Derby. Marlon St. Julien took seventh place in 2000.

"I'm not an activist,” says St. Julien, who admitted during an interview a few years ago that he didn’t know the history of black jockeys and “started reading up on it.” Reached recently in Louisiana, where he is racing the state circuit, he says “I hope I’m a role model as a rider to anyone who wants to race."

Longtime equestrian and Newark, New Jersey, schoolteacher Miles Dean would agree that not enough is known about the nation’s great black jockeys. In an effort to remedy that, he has organized the National Day of the Black Jockey for Memorial Day weekend. The event will include educational seminars, a horse show, parade, and memorial tribute. All events will be held at the Kentucky Exposition Center in Louisville.

Last year, Dean rode his horse, Sankofa, a 12-year-old Arabian stallion, in a six-month journey from New York to California. He spoke at colleges and communities to draw attention to African American contributions to the history and settlement of the United States.

"As an urban educator I see every day the disconnect students have with their past. By acknowledging the contributions of African American jockeys, I hope to heighten children's awareness of their history. It's a history of great achievement, not just a history of enslavement.”