The Most Terrible Polar Exploration Ever: Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic Journey

A century ago, Douglas Mawson saw his two companions die and found himself stranded in the midst of Antarctic blizzards

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120127043104Final_photograph_of_the_Far_Eastern_party1.jpg)

Even today, with advanced foods, and radios, and insulated clothing, a journey on foot across Antarctica is one of the harshest tests a human being can be asked to endure. A hundred years ago, it was worse. Then, wool clothing absorbed snow and damp. High-energy food came in an unappetizing mix of rendered fats called pemmican. Worst of all, extremes of cold pervaded everything; Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who sailed with Captain Scott’s doomed South Pole expedition of 1910-13, recalled that his teeth, “the nerves of which had been killed, split to pieces” and fell victim to temperatures that plunged as low as -77 degrees Fahrenheit.

Cherry-Garrard survived to write an account of his adventures, a book he titled The Worst Journey in the World. But even his Antarctic trek—made in total darkness in the depths of the Southern winter—was not quite so appalling as the desperate march faced one year later by the Australian explorer Douglas Mawson. Mawson’s journey has gone down in the annals of polar exploration as probably the most terrible ever undertaken in Antarctica.

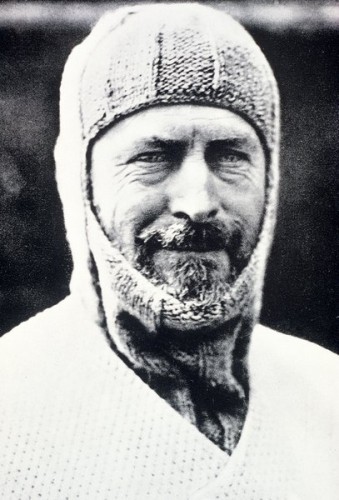

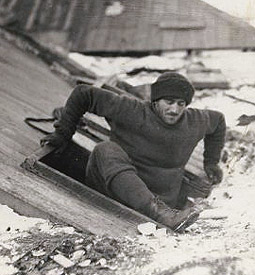

Douglas Mawson, leader and sole survivor of the Far Eastern Sledge Party, in 1913. Photo: Wikicommons.

In 1912, when he set sail across the Southern Ocean, Mawson was 30 years old and already acclaimed as one of the best geologists of his generation. Born in Yorkshire, England, but happily settled in Australia, he had declined the chance to join Robert Falcon Scott’s doomed expedition in order to lead the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, whose chief purpose was to explore and map some of the most remote fastnesses of the white continent. Tall, lean, balding, earnest and determined, Mawson was an Antarctic veteran, a supreme organizer and physically tough.

The Australasian party anchored in Commonwealth Bay, an especially remote part of the Antarctic coast, in January 1912. Over the next few months, wind speeds on the coast averaged 50 m.p.h. and sometimes topped 200, and blizzards were almost constant. Mawson’s plan was to split his expedition into four groups, one to man base camp and the other three to head into the interior to do scientific work. He nominated himself to lead what was known as the Far Eastern Shore Party—a three-man team assigned to survey several glaciers hundreds of miles from base. It was an especially risky assignment. Mawson and his men have the furthest to travel, and hence the heaviest loads to carry, and they would have to cross an area pitted with deep crevasses, each concealed by snow.

Mawson selected two companions to join him. Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis, a British army officer, was the expedition’s dog handler. Ninnis’s close friend Xavier Mertz, was a 28-year-old Swiss lawyer whose chief qualifications for the trek were his idiosyncratic English—a source of great amusement to the other two—his constant high spirits, and his standing as a champion cross-country skier.

A member of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition leans into a 100 m.p.h. wind at base camp to hack out ice for cooking. Photo: Wikicommons.

The explorers took three sledges, pulled by a total of 16 huskies and loaded with a combined 1,720 pounds of food, survival gear and scientific instruments. Mawson limited each man to a minimum of personal possessions. Nennis chose a volume of Thackeray, Mertz a collection of Sherlock Holmes short stories. Mawson took his diary and a photograph of his fiancée, an upper-class Australian woman named Francisca Delprait, but known to all as Paquita.

At first Mawson’s party made good time. Departing from Commonwealth Bay on November 10, 1912, they traveled 300 miles by December 13. Almost everything was going according to plan; the three men reduced their load as they ate their way through their supplies, and only a couple of sick dogs had hindered their progress.

Even so, Mawson felt troubled by a series of peculiar incidents which—he would write later—might have suggested to a superstitious man that something was badly amiss. First he had a strange dream one night, a vision of his father. Mawson had left his parents in good health, but the dream occurred, he would later realize, shortly after his father had unexpectedly sickened and died. Then the explorers found one husky, which had been pregnant, devouring her own puppies. This was normal for dogs in such extreme conditions, but it unsettled the men—doubly so when, far inland and out of nowhere, a petrel smashed into the side of Ninnis’s sledge. “Where could it have come from?” Mertz scribbled in his notebook.

Now a series of near-disasters made the men begin to feel that their luck must be running out. Three times Ninnis almost plunged into concealed cracks in the ice. Mawson was suffering from a split lip that sent shafts of pain shooting across the left side of his face. Ninnis had a bout of snow-blindness and developed an abcess at the tip of one finger. When the pain became too much for him to bear, Mawson lanced it with a pocket knife—without benefit of anesthetic.

On the evening of December 13, 1912, the three explorers pitched camp in the middle of yet another glacier. Mawson abandoned one of their three sledges and redistributed the load on the two others. Then the men slept fitfully, disturbed by distant booms and cracking deep below them. Mawson and Ninnis did not know what to make of the noises, but they frightened Mertz, whose long experience of snowfields taught him that warmer air had made the ground ahead of them unstable. “The snow masses must have been collapsing their arches,” he wrote. “The sound was like the distant thunder of cannon.”

Next day dawned sunny and warm by Antarctic standards, just 11 degrees below freezing. The party continued to make good time, and at noon Mawson halted briefly to shoot the sun in order to determine their position. He was standing on the runners of his moving sledge, completing his calculations, when he became aware that Mertz, who was skiing ahead of the sledges, had stopped singing his Swiss student songs and had raised one ski pole in the air to signal that he had encountered a crevasse. Mawson called back to warn to Ninnis before returning to his calculations. It was only several minutes later that he noticed that Mertz had halted again and was looking back in alarm. Twisting around, Mawson realized that Ninnis and his sledge and dogs had vanished.

Mawson and Mertz hurried back a quarter-mile to where they had crossed the crevasse, praying that their companion had been lost to view behind a rise in the ground. Instead they discovered a yawning chasm in the snow 11 feet across. Crawling forward on his stomach and peering into the void, Mawson dimly made out a narrow ledge far below him. He saw two dogs lying on it: one dead, the other moaning and writhing. Below the ledge, the walls of the crevasse plunged down into darkness.

Frantically, Mawson called Ninnis’s name, again and again. Nothing came back but the echo. Using a knotted fishing line, he sounded the depth to the ice ledge and found it to be 150 feet—too far to climb down to. He and Mertz took turns calling for their companion for more than five hours, hoping that he had merely been stunned. Eventually, giving up, they pondered the mystery of why Ninnis had plunged into a crevasse that the others had crossed safely. Mawson concluded that his companion’s fatal error had been to run beside his sledge rather than stand astride its runners, as he had done. With his weight concentrated on just a few square inches of snow, Ninnis had exceeded the load that the crevasse lid would bear. The fault, though, was Mawson’s; as leader, he could have insisted on skis, or at least snowshoes, for his men.

Mawson and Mertz read the burial service at the lip of the void and paused to take stock. Their situation was clearly desperate. When the party had split their supplies between the two remaining sledges, Mawson had assumed that the lead sled was far more likely to encounter difficulties, so Ninnis’s sledge had been loaded with most of their food supplies and their tent. “Practically all the food had gone— spade, pick, tent,” Mawson wrote. All that remained was sleeping bags and food to last a week and a half. “We considered it a possibility to get through to Winter Quarters by eating dogs,” he added, “so 9 hours after the accident started back, but terribly handicapped. May God help us.”

Lieutenant Ninnis running alongside his sledge, a habit that would cost him his life—and risk those of the two companions he left behind.

The first stage of the return journey was a “mad dash,” Mawson noted, to the spot where they had camped the previous night. There he and Mertz recovered the sledge they had abandoned, and Mawson used his pocket knife to hack its runners into poles for some spare canvas. Now they had shelter, but there was still the matter of deciding how to attempt the return journey. They had left no food depots on their way out; their choices were to head for the sea—a route that was longer but offered the chance of seals to eat and the slim possibility that they might sight the expedition’s supply ship—or to go back the way they’d come. Mawson selected the latter course. He and Mertz killed the weakest of their remaining dogs, ate what they could of its stringy flesh and liver, and fed what was left to the other huskies.

For the first few days they made good time, but soon Mawson went snow-blind. The pain was agonizing, and though Mertz bathed his leader’s eyes with a solution of zinc sulphate and cocaine, the pair had to slow down. Then they marched into a whiteout, seeing “nothing but greyness,” Mertz scribbled in his notebook, and two huskies collapsed. The men had to harness themselves to the sled to continue.

Each night’s rations were less palatable than the last. Learning by experiment, Mawson found that “it was worth the while spending some time in boiling the dogs’ meat thoroughly. Thus a tasty soup was prepared as well as a supply of edible meat in which the muscular tissue and the gristle were reduced to the consistency of a jelly. The paws took longest of all to cook, but, treated to lengthy stewing, they became quite digestible.” Even so, the two men’s physical condition rapidly deteriorated. Mertz, Mawson wrote in his diary on January 5, 1913, “is generally in a very bad condition… skin coming off legs, etc.” Despite his leader’s desperation to keep moving, Mertz insisted that a day’s rest might revive him, and the pair spent 24 hours huddled in their sleeping bags.

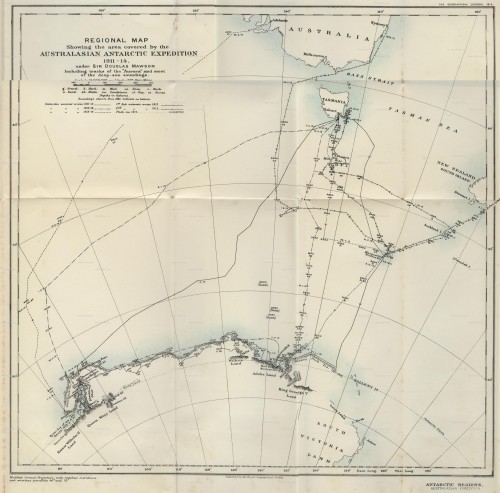

The route taken by the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, showing glaciers Mawson named for Mertz and Ninnis. Click to view in higher resolution.

“Things are in a most serious state for both of us—if he cannot go 8 or 10 m a day, in a day or two we are doomed,” Mawson wrote on January 6. “I could pull through myself with the provisions at hand but I cannot leave him. His heart seems to have gone. It is very hard for me—to be within 100 m of the Hut and in such a position is awful.”

The next morning Mawson awoke to find his companion delirious; worse, he had developed diarrhea and fouled himself inside his sleeping bag. It took Mawson hours to clean him up and put him back inside his bag to warm up, and then, he added, just a few minutes later, “I him in a kind of fit.” They began moving again, and Mertz took some cocoa and beef tea, but the fits got worse and he fell into a delirium. They stopped to make camp, Mawson wrote, but “at 8pm he raves & breaks a tent pole…. Continues to rave for hours. I hold him down, then he becomes more peaceful & I put him quietly in the bag. He dies peacefully at about 2am in the morning of 8th. Death due to exposure finally bringing on a fever.”

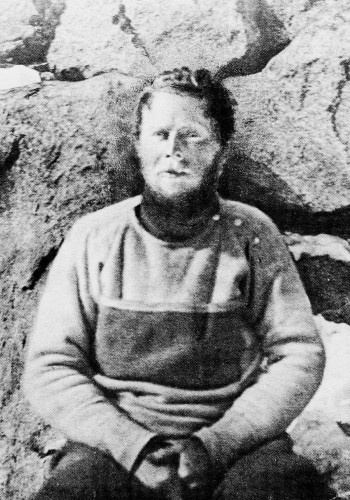

A haunted Douglas Mawson pictured early in 1913, recuperating at base camp after his solo ordeal in the Antarctic.

Mawson was now alone, at least 100 miles from the nearest human being, and in poor physical condition. “The nose and lips break open,” he wrote, and his groin was “getting in a painfully raw condition due to reduced condition, dampness and friction in walking.” The explorer would admit later that he felt “utterly overwhelmed by an urge to give in.” Only determination to survive for Paquita, and to give an account of his two dead friends, drove him on.

At 9 a.m. on January 11 the wind finally died away. Mawson had passed the days since Mertz’s death productively. Using his now blunt knife, he had cut the one remaining sledge in two; he resewed his sail; and, remarkably, he found the strength to drag Mertz’s body out of the tent and entomb it beneath a cairn of ice blocks he hacked out of the ground. Then he began to trudge toward the endless horizon, hauling his half-sledge.

Within a few miles, Mawson’s feet became so painful that each step was an agony; when he sat on his sledge and removed his boots and socks to investigate, he found that the skin on his soles had come away, leaving nothing but a mass of weeping blisters. Desperate, he smeared his feet with lanolin and bandaged the loose skin back to them before staggering on. That night, curled up in his makeshift tent, he wrote:

My whole body is apparently rotting from want of proper nourishment—frost-bitten fingertips, festerings, mucous membrane of nose gone, saliva glands of mouth refusing duty, skin coming off the whole body.

The next day, Mawson’s feet were too raw to walk. On January 13 he marched again, dragging himself toward the glacier he had named for Mertz, and by the end of that day he could see in the far distance the high uplands of the vast plateau that terminated at base camp. By now he could cover little more than five miles a day.

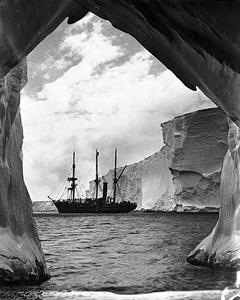

The steamship Aurora, which rescued Mawson and his companions from the bleak confines of their base camp.

Mawson’s greatest fear was that he, too, would stumble into a crevasse, and on January 17, he did. By a piece of incredible good fortune, however, the fissure that opened was a little narrower than his half-sledge. With a jerk that all but snapped his fragile body clean in two, Mawson found himself dangling 14 feet down above an apparently bottomless pit, spinning slowly on his fraying rope. He could sense

the sledge creeping to the mouth . I had time to say to myself, ‘So this is the end,’ expecting every moment the sledge to crash on my head and both of us to go to the bottom unseen below. Then I thought of the food left uneaten on the sledge, and…of Providence again giving me a chance. The chance looked very small as the rope had sawed into the overhanging lid, my finger ends all damaged, myself weak.

Making a “great struggle,” Mawson inched up the rope, hand over hand. Several times he lost his grip and slipped back. But the rope held. Sensing that he had the strength for one final attempt, the explorer clawed his way to the lip of the crevasse, every muscle spasming, his raw fingers slippery with blood. “At last I just did it,” he recalled, and dragged himself clear. Spent, he lay by the edge of the chasm for an hour before he recovered sufficiently to drag open his packs, erect the tent and crawl into his bag to sleep.

That night, lying in his tent, Mawson fashioned a rope ladder, which he anchored to his sledge and attached to his harness. Now, if he were to fall again, getting out of a crevasse ought to be easier. The theory was put to the test the following day, when the ladder saved him from another dark plummet into ice.

Toward the end of January, Mawson was reduced to four miles of marching a day; his energy was sapped by the need to dress and redress his many injuries. His hair began to fall out, and he found himself pinned down by another blizzard. Desperate, he marched eight miles into the gale before struggling to erect his tent.

The next morning, the forced march seemed worth it: Mawson emerged from the tent into bright sunshine—and to the sight of the coastline of Commonwealth Bay. He was only 40 miles from base, and little more than 30 from a supply dump called Aladdin’s Cave, which contained a cache of supplies.

Not the least staggering of Mawson’s achievements on his return was the precision of his navigation. On January 29, in another gale, he spotted a low cairn just 300 yards off the path of his march. It proved to mark a note and a store of food left by his worried companions at base camp. Emboldened, he pressed on, and on February 1 reached the entrance to Aladdin’s Cave, where he wept to discover three oranges and a pineapple—overcome, he later said, by the sight of something that was not white.

As Mawson rested that night, the weather closed in again, and for five days he was confined to his ice hole as one of the most vicious blizzards he had ever known raged over him. Only when the storm dropped on February 8 did he find his way to base at last–just in time to see the expedition’s ship, Aurora, leaving for Australia. A shore party had been left to wait for him, but it was too late for the ship to turn, and Mawson found himself forced to spend a second winter in Antarctica. In time, he would come to view this as a blessing; he needed the gentle pace of life, and the solicitude of his companions, to recover from his trek.

There remains the mystery of what caused the illness that claimed Mertz’s life and so nearly took Mawson’s. Some polar experts are convinced that the problem was merely poor diet and exhaustion, but doctors have suggested it was caused by husky meat—specifically, the dogs’ vitamin-enriched livers, which contain such high concentrations of Vitamin A that they can bring on a condition known as “hypervitaminosis A”–a condition that causes drying and fissuring of the skin, hair loss, nausea and, in high doses, madness, precisely the symptoms displayed by the fortunate Douglas Mawson, and the luckless Xavier Mertz.

Sources

Philip Ayres. Mawson: A Life. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2003; Michael Howell and Peter Ford. The Ghost Disease and Twelve Other Stories of Detective Work in the Medical Field. London: Penguin, 1986; Fred & Eleanor Jack. Mawson’s Antarctic Diaries. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988; Douglas Mawson. The Home of the Blizzard: A True Story of Antarctic Survival. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2000.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)