The Secrets of Easter Island

The more we learn about the remote island from archaeologists and researchers, the more intriguing it becomes

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from its original form and updated to include new information for Smithsonian’s Mysteries of the Ancient World bookazine published in Fall 2009.

“There exists in the midst of the great ocean, in a region where nobody goes, a mysterious and isolated island,” wrote the 19th-century French seafarer and artist Pierre Loti. “The island is planted with monstrous great statues, the work of I don’t know what race, today degenerate or vanished; its great remains an enigma.” Named Easter Island by the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who first spied it on Easter Day 1722, this tiny spit of volcanic rock in the vast South Seas is, even today, the most remote inhabited place on earth. Its nearly 1,000 statues, some almost 30 feet tall and weighing as much as 80 tons, are still an enigma, but the statue builders are far from vanished. In fact, their descendants are making art and renewing their cultural traditions in an island renaissance.

To early travelers, the spectacle of immense stone figures, at once serenely godlike and savagely human, was almost beyond imagining. The island’s population was too small, too primitive and too isolated to be credited with such feats of artistry, engineering and labor. “We could hardly conceive how these islanders, wholly unacquainted with any mechanical power, could raise such stupendous figures,” the British mariner Capt. James Cook wrote in 1774. He freely speculated on how the statues might have been raised, a little at a time, using piles of stones and scaffolding; and there has been no end of speculation, and no lack of scientific investigation, in the centuries that followed. By Cook’s time, the islanders had toppled many of their statues and were neglecting those left standing. But the art of Easter Island still looms on the horizon of the human imagination.

Just 14 miles long and 7 miles wide, the island is more than 2,000 miles off the coast of South America and 1,100 miles from its nearest Polynesian neighbor, Pitcairn Island, where mutineers from the HMS Bounty hid in the 19th century. Too far south for a tropical climate, lacking coral reefs and perfect beaches, and whipped by perennial winds and seasonal downpours, Easter Island nonetheless possesses a rugged beauty—a mixture of geology and art, of volcanic cones and lava flows, steep cliffs and rocky coves. Its megalithic statues are even more imposing than the landscape, but there is a rich tradition of island arts in forms less solid than stone—in wood and bark cloth, strings and feathers, songs and dances, and in a lost form of pictorial writing called rongorongo, which has eluded every attempt to decipher it. A society of hereditary chiefs, priests, clans and guilds of specialized craftsmen lived in isolation for 1,000 years.

History, as much as art, made this island unique. But attempts to unravel that history have produced many interpretations and arguments. The missionary’s anecdotes, the archaeologist’s shovel, the anthropologist’s oral histories and boxes of bones have all revealed something of the island’s story. But by no means everything. When did the first people arrive? Where did they come from? Why did they carve such enormous statues? How did they move them and raise them up onto platforms? Why, after centuries, did they topple these idols? Such questions have been answered again and again, but the answers keep changing.

Over the past few decades, archaeologists have assembled evidence that the first settlers came from another Polynesian island, but they can’t agree on which one. Estimates of when people first reached the island are as varied, ranging from the first to the sixth century A.D. And how they ever found the place, whether by design or accident, is yet another unresolved question.

Some argue that the navigators of the first millennium could never have plotted a course over such immense distances without modern precision instruments. Others contend that the early Polynesians were among the world’s most skilled seafarers—masters of the night sky and the ocean’s currents. One archaeoastronomer suggests that a new supernova in the ancient skies may have pointed the way. But did the voyagers know the island was even there? For that, science has no answer. The islanders, however, do.

Benedicto Tuki was a tall 65-year-old master wood-carver and keeper of ancient knowledge when I met him. (Tuki has since died.) His piercing eyes were set in a deeply creased, mahogany face. He introduced himself as a descendant of the island’s first king, Hotu Matu’a, who, he said, brought the original settlers from an island named Hiva in the Marquesas. He claimed his grandmother was the island’s last queen. He would tell me about Hotu Matu’a, he said that day, but only from the center of the island, at a platform called Ahu Akivi with its seven giant statues. There, he could recount the story in the right way.

In Tuki’s native tongue, the island—like the people and the language—is called Rapa Nui. Platforms are called ahu, and the statues that sit on them, moai (pronounced mo-eye). As our jeep negotiated a rutted dirt road, the seven moai loomed into view. Their faces were paternal, all-knowing and human—forbiddingly human. These seven, Tuki said, were not watching over the land like those statues with their backs to the sea. These stared out beyond the island, across the ocean to the west, remembering where they came from. When Hotu Matu’a arrived on the island, Tuki added, he brought seven different races with him, which became the seven tribes of Rapa Nui. These moai represent the original ancestor from the Marquesas and the kings of other Polynesian islands. Tuki himself gazed into the distance as he chanted their names. “This is not written down,” he said. “My grandmother told me before she died.” His was the 68th generation, he added, since Hotu Matu’a.

Because of fighting at home, Tuki continued, chief Hotu Matu’a gathered his followers for a voyage to a new land. His tattooist and priest, Hau Maka, had flown across the ocean in a dream and seen Rapa Nui and its location, which he described in detail. Hotu Matu’a and his brother-in-law set sail in long double canoes, loaded with people, food, water, plant cuttings and animals. After a voyage of two months, they sailed into Anakena Bay, which was just as the tattooist had described it.

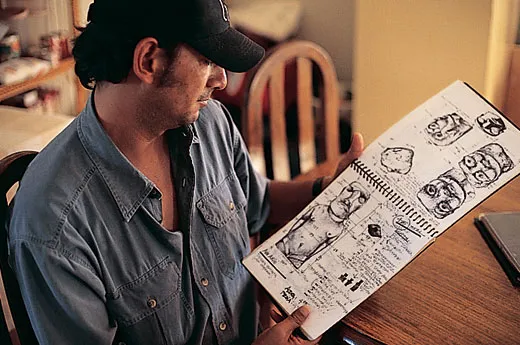

Sometimes, says Cristián Arévalo Pakarati, an island artist who has worked with several archaeologists, the old stories hold as much truth as anything the scientists unearth. He tells me this as we climb up the cone of a volcano called Rano Raraku to the quarry where the great moai were once carved. The steep path winds through an astonishing landscape of moai, standing tilted and without order, many buried up to their necks, some fallen facedown on the slope, apparently abandoned here before they were ever moved. Pakarati is dwarfed by a stone head as he stops to lean against it. “It’s hard to imagine,” he says, “how the carvers must have felt when they were told to stop working. They’d been carving these statues here for centuries, until one day the boss shows up and tells them to quit, to go home, because there’s no more food, there’s a war and nobody believes in the statue system anymore!” Pakarati identifies strongly with his forebears; working with Jo Anne Van Tilburg, an archaeologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, he’s spent many years making drawings and measurements of all the island’s moai. (He and Van Tilburg have also teamed up to create the new Galería Mana, intended to showcase and sustain traditional artisanry on the island.)

Now, as Pakarati and I climb into the quarry itself, he shows me where the carving was done.The colossal figures are in every stage of completion, laid out on their backs with a sort of stone keel attaching them to the bedrock. Carved from a soft stone called lapilli tuff, a compressed volcanic ash, several figures lie side by side in a niche. “These people had absolute control over the stone,” Pakarati says of the carvers. “They could move statues from here to Tahai, which is 15 kilometers away, without breaking the nose, the lips, the fingers or anything.” Then he points to a few broken heads and bodies on the slope below and laughs. “Obviously, accidents were allowed.”

When a statue was almost complete, the carvers drilled holes through the keel to break it off from the bedrock, then slid it down the slope into a big hole, where they could stand it up to finish the back. Eye sockets were carved once a statue was on its ahu, and white coral and obsidian eyes were inserted during ceremonies to awaken the moai’s power. In some cases, the statues were adorned with huge cylindrical hats or topknots of red scoria, another volcanic stone. But first a statue had to be moved over one of the roads that led to the island’s nearly 300 ahu. How that was done is still a matter of dispute. Rapa Nui legends say the moai “walked” with the help of a chief or priest who had mana, or supernatural power. Archaeologists have proposed other methods for moving the statues, using various combinations of log rollers, sledges and ropes.

Trying to sort out the facts of the island’s past has led researchers into one riddle after another—from the meaning of the monuments to the reasons for the outbreak of warfare and the cultural collapse after a thousand years of peace. Apart from oral tradition, there is no historical record before the first European ships arrived. But evidence from many disciplines, such as the excavation of bones and weapons, the study of fossilized vegetation, and the analysis of stylistic changes in the statues and petroglyphs allows a rough historical sketch to emerge: the people who settled on the island found it covered with trees, a valuable resource for making canoes and eventually useful in transporting the moai. They brought with them plants and animals to provide food, although the only animals that survived were chickens and tiny Polynesian rats. Artistic traditions, evolving in isolation, produced a rich imagery of ornaments for the chiefs, priests and their aristocratic lineages. And many islanders from the lower-caste tribes achieved status as master carvers, divers, canoe builders or members of other artisan’s guilds. Georgia Lee, an archaeologist who spent six years documenting the island’s petroglyphs, finds them as remarkable as the moai. “There’s nothing like it in Polynesia,” she says of this rock art. “The size, scope, beauty of designs and workmanship is extraordinary.”

At some point in the island’s history, when both the art and the population were increasing, the island’s resources were overtaxed. Too many trees had been cut down. “Without trees you’ve got no canoes,” says Pakarati. “Without canoes you’ve got no fish, so I think people were already starving when they were carving these statues. The early moai were thinner, but these last statues have great curved bellies. What you reflect in your idols is an ideal, so when everybody’s hungry, you make them fat, and big.” When the islanders ran out of resources, Pakarati speculates, they threw their idols down and started killing each other.

Some archaeologists point to a layer of subsoil with many obsidian spear points as a sign of sudden warfare. Islanders say there was probably cannibalism, as well as carnage, and seem to think no less of their ancestors because of it. Smithsonian forensic anthropologist Douglas Owsley, who has studied the bones of some 600 individuals from the island, has found numerous signs of trauma, such as blows to the face and head. But only occasionally, he says, did these injuries result in death. In any case, a population that grew to as many as 20,000 was reduced to only a few thousand at most when the captains of the first European ships counted them in the early 18th century. Over the next 150 years, with visits by European and American sailors, French traders and missionaries, Peruvian slave raiders, Chilean imperialists and Scottish ranchers (who introduced sheep and herded the natives off the land, fencing them into one small village), the Rapa Nui people were all but destroyed. By 1877 there were only 110 natives left on the island.

Although the population rebounded steadily through the 20th century, native islanders still don’t own their land. The Chilean government claimed possession of Easter Island in 1888 and, in 1935, designated it a national park, to preserve thousands of archaeological sites. (Archaeologist Van Tilburg estimates that there could be as many as 20,00o sites on the island.) Today, about 2,000 native people and about as many Chileans crowd into the island’s only village, Hanga Roa, and its outskirts. Under growing pressure, the Chilean government is giving back a small number of homesteads to native families, alarming some archaeologists and stirring intense debate. But though they remain largely dispossessed, the Rapa Nui people have re-emerged from the shadows of the past, recovering and reinventing their ancient art and culture.

Carving a small wooden moai in his yard, Andreas Pakarati, who goes by Panda, is part of that renewal. “I’m the first professional tattooist on the island in 100 years,” he says, soft eyes flashing under a rakish black beret. Panda’s interest was stirred by pictures he saw in a book as a teenager, and tattoo artists from Hawaii and other Polynesian islands taught him their techniques. He has taken most of his designs from Rapa Nui rock art and from Georgia Lee’s 1992 book on the petroglyphs. “Now,” says Panda, “the tattoo is reborn.”

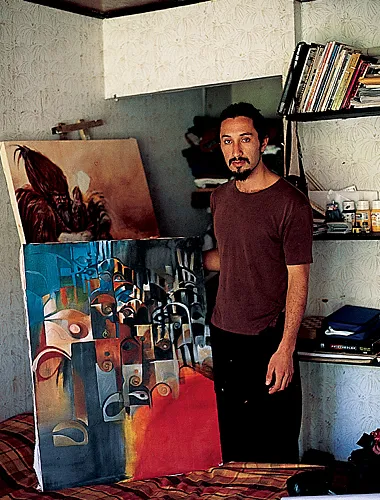

Other artists of Panda’s generation are also breathing new life into old art. In his small studio that doubles as living space, the walls lined with large canvases of Polynesian warriors and tattooed faces, Cristián Silva paints Rapa Nui themes with his own touch of swirling surrealism. “I paint because I appreciate my culture,” he says. “The moai are cool, and I feel connected to ancestral things. On this island you can’t escape that! But I don’t copy them. I try to find a different point of view.”

The dancers and musicians of the Kari Kari company, shouting native chants and swaying like palms in the wind, are among the most striking symbols of renewal. “We’re trying to keep the culture alive,” says Jimmy Araki, one of the musicians. “We’re trying to recuperate all our ancient stuff and put it back together, and give it a new uprising.” Dancer Carolina Edwards, 22, arrives for a rehearsal astride a bright red all-terrain vehicle, ducks behind some pickup trucks on a hill overlooking one of the giant statues and emerges moments later in the ancient dress of Rapa Nui women, a bikini made of tapa, or bark cloth. “When I was little they used to call me tokerau, which means wind, because I used to run a lot, and jump out of trees,” she says, laughing. “Most of the islanders play guitar and know how to dance. We’re born with the music.”

But some scholars, and some islanders, say the new forms have less to do with ancient culture than with today’s tourist dollars. “What you have now is reinventing,” says Rapa Nui archaeologist Sergio Rapu, a former governor of the island. “But the people in the culture don’t like to say we’re reinventing. So you have to say, ‘OK, that’s Rapa Nui culture.’ It’s a necessity. The people are feeling a lack of what they lost.”

Even the oldest and most traditional of artisans, like Benedicto Tuki, agree that tourists provide essential support for their culture—but he insisted, when we spoke, that the culture is intact, that its songs and skills carry ancient knowledge into the present. Grant McCall, an anthropologist from the University of New South Wales in Australia, concurs. When I ask McCall, who has recorded the genealogies of island families since 1968, how a culture could be transmitted through only 110 people, he tugs at his scruffy blond mustache. “Well, it only takes two people,” he says, “somebody who is speaking and somebody who is listening.”

Since many families’ claims to land are based on their presumed knowledge of ancestral boundaries, the argument is hardly academic. Chilean archaeologist Claudio Cristino, who spent 25 years documenting and restoring the island’s treasures, frames the debate in dramatic terms. “There are native people on the island, and all over the world, who are using the past to recover their identities, land and power,” he says. Sitting in his office at the University of Chile in Santiago, he is not sanguine. “As a scientist, I’ve spent half my life there. It’s my island! And now people are already clearing land and plowing it for agriculture, destroying archaeological sites. Behind the statues you have people with their dreams, their needs to develop the island. Are we as scientists responsible for that? The question is, who owns the past?” Who, indeed? The former mayor of Hanga Roa, Petero Edmunds, who is Rapa Nui, opposes the Chilean government’s plans for giving away land. He wants the entire park returned to Rapa Nui control, to be kept intact. “But they won’t listen,” he says. “They’ve got their fingers in their ears.” And who should look after it? “The people of Rapa Nui who have looked after it for a thousand years,” he answers. He becomes pensive. “The moai are not silent,” he says. “They speak. They’re an example our ancestors created in stone, of something that is within us, which we call spirit. The world must know this spirit is alive.”

UPDATE: According to the UK Telegraph, two British scientists have uncovered new research answering the riddle of why some of the megaliths are crowned by hats carved of red stone.

Colin Richards of the University of Manchester and Sue Hamilton of University College London retraced a centuries-old road that leads to an ancient quarry, where island inhabitants mined red volcanic pumice. They believe that the hats first were first introduced as a distinctive feature between 1200 and 1300, a period when the island’s brooding, mysterious statues were created on a scale larger than before, weighing several tons. The hats, the British experts theorize, may represent a plait or top knot, styles which would have been worn by chieftains then engaged in an epic struggle for dominance. “Chieftain society,” says Hamilton, “was highly competitive and it has been suggested that they were competing so much that they over-ran their resources.”